Attack of the mole man

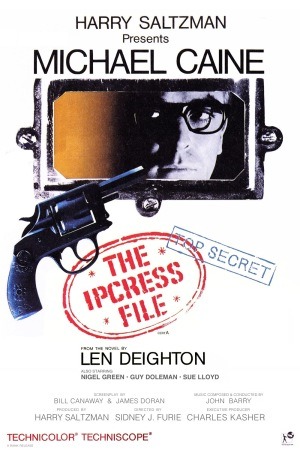

Ah, there's nothing like a good paranoid political thriller! Hard to say when the genre reached its peak - the '60s (e.g The Ipcress File), maybe the '70s (e.g. Three Days of the Condor). Either way, we've been in a low place for really smart espionage films for a while, which means that when I call Breach a throwback, I intend for that to be the highest praise possible.

Here's the very best compliment I can pay the film: it's based on a major news story from only six years ago, and the film opens with a brief clip of then-Attorney General John Ashcroft giving away the ending, and despite this it is as taut a thriller as I've seen in many an age.

Breach is the story of two FBI men: Agent Robert Hanssen (Chris Cooper) and rookie Eric O'Neill (Ryan Phillippe), and what occurred between them after O'Neill was assigned to be Hanssen's assistant and to investigate the older man first for sexual deviancy and then for treason, selling secrets to Russia over a 15 year period. As the historical record and the the pre-credits sequence show, Hanssen was eventually arrested on 18 February, 2001, and is presently in his sixth year of a 25-year sentence.

With a preordained ending like that, there's not much suspense to be drawn out of the story; so screenwriters Adam Mazer and William Rotko and director Billy Ray (whose Shattered Glass also explored the struggle between truth and deception in Washington) wisely ignore the plot, except when it intersects with their real target: the mind games that are part and parcel of life in the Federal Bureau of Investigation. As brilliantly embodied by Cooper, Robert Hanssen is a paranoid, defensive little man, anxious to keep control of his little space of the world, not just because he has been trained to constantly keep watch over his shoulder (though he has been), but for a much more insidious reason: he works in a bureaucracy. That's where all the conflict in Breach comes from, ultimately: pissing matches between cogs in a bureaucracy.

Long before Hanssen admits that much, locked in the back of a van, it's already obvious to the audience. So much of the film is devoted to petty squabbling about who does or doesn't get a window office, to snarling grey-suited dictators obsessively defending their fiefdoms, to competing agencies standing in the way of each other just for the sake of competing. When Hanssen and O'Neill meet, the traitor doesn't trust the nervous young man, but not apparently because he is guilty; it's because he doesn't want someone from the outside treading on his patch.

In other words, Breach is the story of every bored American white class drone in the last fifty years, except in this case, the drone is responsible for billions of dollars damage and an unknown number of human deaths. It's the funhouse version of the modern Everyman, and it needs a central character written and performed with great sensitivity: not too cartoonishly evil as to erase the basic humanity of the man, nor so sympathetic as to ignore the very real damage he has done. It's tightrope that the filmmakers and Chris Cooper navigate perfectly. Robert Hanssen in Breach is a man in full, in possession of a family and faith and an important job, along with dozens of tiny details that flesh out and reinforce those labels. The example that springs to mind is a line tossed out in one scene, with Hanssen admitting he was a doubting Lutheran before his wife made a good orthodox Catholic out of him. The specificity of this comment, and the way that Cooper delivers the line, make it such a rich detail, richer than most movie characters dream of, and it's just one of many moments.

It's a performance in which Hanssen can observe things that are fundamentally unobservable, to prove he's such a good spy, and rather than frown at the contrivance, Cooper makes us believe that yes, there is something to notice, and isn't he marvelously clever for doing so? It's a delicate balance that makes Hanssen incredibly interesting and intelligent, without ever actually tripping into sympathy; for he is also a snarling monster at times, and incredibly abrasive even when he means to be friendly. It is a brilliant performance, the best of Cooper's career, and likely to be on any reasonable shortlist of the best of 2007.

Unsurprisingly, Ryan Phillippe isn't much able to hold his own against a performance like that, but he's still pretty good. For being Ryan Phillippe, and all. There's just not that much for his character to do, is the thing: fret constantly about how many lies he tells, and look sadly at his wife (Caroline Dhavernas, whom you likely didn't see in Wonderfalls because that show was off the air practically before it started, sporting a fantastically inconsistent Eastern Europe accent) every time she asks him what's going on. He acquits himself well enough, I suppose. Much more enjoyable is Laura Linney in a small role as O'Neill's real superior, a hard-ass with a heart of hard-assery. The script almost begs for the character to be injected with bits of pathos near the end, which Linney wisely refuses to do.

As is so often the case in a film with a strong central character, it's easy to ignore what's happening on the periphery. Ray has a good sense for place, and this is probably the first film about the FBI that doesn't feel like it's in some fantastic land of myth: there are boxes cluttering up the halls, ugly institutional grey paint on every surface, and the control room for the Hanssen case - the most important case in the Bureau at that time - is cramped and cluttered and a little bit like a lunchroom; it's the most unsexy thing I've ever seen in a movie like this. Desexing the FBI may or may not be a noble goal, but it's probably an honest one, as attested to by the presence of one Eric O'Neill as an advisor to the film.

One thing that did bother me, for an entirely shallow reason: for the whole film, I kept thinking it was shot with the same unglamourous, flat, office-like look of the ur-FBI picture, The Silence of the Lambs. Fair, but cheap, thought I; get yourself some easy and sort of undeserved cred by exactly copying your betters. Then the credits come up, and I find that the Breach cinematographer was...Tak Fujimoto. Who shot The Silence of the Lambs. And has apparently learned not one new technique in the last 16 years.

Of course, it worked then and it would have worked now if I weren't such a wanker. Like I said at the top, there's not anything inherently wrong with a throwback.

8/10

Here's the very best compliment I can pay the film: it's based on a major news story from only six years ago, and the film opens with a brief clip of then-Attorney General John Ashcroft giving away the ending, and despite this it is as taut a thriller as I've seen in many an age.

Breach is the story of two FBI men: Agent Robert Hanssen (Chris Cooper) and rookie Eric O'Neill (Ryan Phillippe), and what occurred between them after O'Neill was assigned to be Hanssen's assistant and to investigate the older man first for sexual deviancy and then for treason, selling secrets to Russia over a 15 year period. As the historical record and the the pre-credits sequence show, Hanssen was eventually arrested on 18 February, 2001, and is presently in his sixth year of a 25-year sentence.

With a preordained ending like that, there's not much suspense to be drawn out of the story; so screenwriters Adam Mazer and William Rotko and director Billy Ray (whose Shattered Glass also explored the struggle between truth and deception in Washington) wisely ignore the plot, except when it intersects with their real target: the mind games that are part and parcel of life in the Federal Bureau of Investigation. As brilliantly embodied by Cooper, Robert Hanssen is a paranoid, defensive little man, anxious to keep control of his little space of the world, not just because he has been trained to constantly keep watch over his shoulder (though he has been), but for a much more insidious reason: he works in a bureaucracy. That's where all the conflict in Breach comes from, ultimately: pissing matches between cogs in a bureaucracy.

Long before Hanssen admits that much, locked in the back of a van, it's already obvious to the audience. So much of the film is devoted to petty squabbling about who does or doesn't get a window office, to snarling grey-suited dictators obsessively defending their fiefdoms, to competing agencies standing in the way of each other just for the sake of competing. When Hanssen and O'Neill meet, the traitor doesn't trust the nervous young man, but not apparently because he is guilty; it's because he doesn't want someone from the outside treading on his patch.

In other words, Breach is the story of every bored American white class drone in the last fifty years, except in this case, the drone is responsible for billions of dollars damage and an unknown number of human deaths. It's the funhouse version of the modern Everyman, and it needs a central character written and performed with great sensitivity: not too cartoonishly evil as to erase the basic humanity of the man, nor so sympathetic as to ignore the very real damage he has done. It's tightrope that the filmmakers and Chris Cooper navigate perfectly. Robert Hanssen in Breach is a man in full, in possession of a family and faith and an important job, along with dozens of tiny details that flesh out and reinforce those labels. The example that springs to mind is a line tossed out in one scene, with Hanssen admitting he was a doubting Lutheran before his wife made a good orthodox Catholic out of him. The specificity of this comment, and the way that Cooper delivers the line, make it such a rich detail, richer than most movie characters dream of, and it's just one of many moments.

It's a performance in which Hanssen can observe things that are fundamentally unobservable, to prove he's such a good spy, and rather than frown at the contrivance, Cooper makes us believe that yes, there is something to notice, and isn't he marvelously clever for doing so? It's a delicate balance that makes Hanssen incredibly interesting and intelligent, without ever actually tripping into sympathy; for he is also a snarling monster at times, and incredibly abrasive even when he means to be friendly. It is a brilliant performance, the best of Cooper's career, and likely to be on any reasonable shortlist of the best of 2007.

Unsurprisingly, Ryan Phillippe isn't much able to hold his own against a performance like that, but he's still pretty good. For being Ryan Phillippe, and all. There's just not that much for his character to do, is the thing: fret constantly about how many lies he tells, and look sadly at his wife (Caroline Dhavernas, whom you likely didn't see in Wonderfalls because that show was off the air practically before it started, sporting a fantastically inconsistent Eastern Europe accent) every time she asks him what's going on. He acquits himself well enough, I suppose. Much more enjoyable is Laura Linney in a small role as O'Neill's real superior, a hard-ass with a heart of hard-assery. The script almost begs for the character to be injected with bits of pathos near the end, which Linney wisely refuses to do.

As is so often the case in a film with a strong central character, it's easy to ignore what's happening on the periphery. Ray has a good sense for place, and this is probably the first film about the FBI that doesn't feel like it's in some fantastic land of myth: there are boxes cluttering up the halls, ugly institutional grey paint on every surface, and the control room for the Hanssen case - the most important case in the Bureau at that time - is cramped and cluttered and a little bit like a lunchroom; it's the most unsexy thing I've ever seen in a movie like this. Desexing the FBI may or may not be a noble goal, but it's probably an honest one, as attested to by the presence of one Eric O'Neill as an advisor to the film.

One thing that did bother me, for an entirely shallow reason: for the whole film, I kept thinking it was shot with the same unglamourous, flat, office-like look of the ur-FBI picture, The Silence of the Lambs. Fair, but cheap, thought I; get yourself some easy and sort of undeserved cred by exactly copying your betters. Then the credits come up, and I find that the Breach cinematographer was...Tak Fujimoto. Who shot The Silence of the Lambs. And has apparently learned not one new technique in the last 16 years.

Of course, it worked then and it would have worked now if I weren't such a wanker. Like I said at the top, there's not anything inherently wrong with a throwback.

8/10

Categories: political movies, spy films, thrillers