Summer of Blood: B-Horror in the 1960s - A lovely group of people who just happen to be...

There are enough Psycho knock-offs in the world to keep you busy for as long as you could possibly stand it, but there never was a Psycho knock-off quite as overt about it, yet at the same time as creative and effective in its own right, as Homicidal. It's one of the earliest of its breed, coming to theaters in the summer of 1961, less than a year after Hitchcock's groundbreaking work, and the screenplay by Robb White is precisely the thing that you'd expect when a producer gave the order to copy this other movie exactly, but make every single detail a tiny bit different. And I don't meant that as a slight on White at all - viewed solely as a Psycho riff, Homicidal is downright inspired in the way it jostles elements into a brand new configuration. Still, it's good for the film that the producer in question, who was also the director, was the legendary William Castle, who for a brief period as the '50s turned into the '60s combined in one body the savviest instincts of a marketing guru with the nonsensical ebullience of an old-fashioned carnival barker and an abiding enthusiasm for cinema as a playground to just go and and have fun, as either a filmmaker or an audience member.

The savvy instinct is what led him to copy American cinema's biggest talking point of 1960, of course, but it's the enthusiasm that makes Homicidal such an appealing watch - certainly one of the best of the wannabe Psychos. It lacks the cheerful campiness of Castle's best-known films, The Tingler and House on Haunted Hill, both made in 1959 and both starring Vincent Price, patron saint of cheerful campiness. Indeed, besides the very opening and up until a key moment near the end, the film doesn't openly cop to any sense of humor at all, instead focusing sustaining its grim mystery and overall tension. Neither of those things are necessarily the film's best strength: William Castle was not, on his very best day, Alfred Hitchcock. But seeing the elements of Hitchcock as reworked by an aesthetic sensibility trained on matinee movies is a delight no matter what. Straitlaced as it undeniably is, Homicidal is shot through with a trashy glee in the things it can get away with.

It opens with its biggest single joke: Castle himself appears onscreen (as he tended to do) to introduce us to his latest masterwork, after briefly reminding us what some of his recent hits have been, all while calmly doing needlepoint. I love William Castle. And I love him all the more since the needlepoint he's been working on is the film's title, done in a homey font. From here, we head back to the past of the central family, one of the most fucked-up in any '60s film not based on the plays of Tennessee Williams. And we also head straight into the script's dogged refusal to clarify more than it absolutely has to, since all we see in the prologue is a little boy named Warren stealing a doll from a little girl whose name we never pick up, nor is their relationship clarified. Then we skip ahead to Ventura, CA: today. Not today. 1961 today. And here we find Miriam Webster (Joan Marshall), furtively checking into the Hotel Ventura with an obvious basketful of noir-heroine-on-the-run mystery, like we haven't just wandered into Psycho, we've skipped right ahead to the third reel. Miriam picks the youngest, handsomest bellhop (Richard Rust) to help her with the bags, and when she's got him alone in the room, she springs her highly abbreviated tale of woe: for the enormous sum of $2000, she'd like him to marry her, and get an annulment immediately. But they need to get married tonight. That kind of unthinkably large tip, plus the promise to hang around all evening with a beautiful woman, are enough to overcome his natural confusion at the situation, and late that night, they're on their way to a justice of the peace named Adrims (James Westerfield). No sooner has he completed the ceremony than Miriam pulls out a knife and stabs Adrims to death, fleeing before any of the witnesses or her dumbfounded new husband have had a chance to react.

That is just about as bravura as openings get: in terms of jaw-dropping madness per square inch and a desire to find out what the hell is going on, it's right up there with Samuel Fuller's crazed opening scene in The Naked Kiss. I can only imagine how it must have played in '61: the stabbing itself is magnificently disgusting, with squelchy stabbing noises that put the famed casaba melon of Psycho to shame, and while we never see the knife enter poor Adrims, the way he feebly paws at the spreading wet mass seeping into his shirt leaves even less to the imagination than the violence befalling Marion Crane in that doomed shower. The violence is shocking enough, in context (since even several decades later, anybody watching a William Castle picture isn't anticipating that kind of intense violence, and the director's joshing tone in the opening is hardly meant to give us an expectation of any kind of darkness to follow), that it even trumps how manifestly unclear anything in the plot is, to this point.

And, as it happens, as unclear as much of it remains. Homicidal is not a film bogged down by needless exposition, nor by much exposition at all, even down to the level of character relationships. We meet people, and we can tell that they're to be important down the line, but the film doesn't put much effort into clarifying why until it's actually important. So I'm not going to tell you how all of these people fit together: Miriam, it turns out, is actually a woman named Emily, and she's taking care of an elderly mute invalid, Helga (Eugenie Leontovich), whom she plainly doesn't like at all, given the first thing she does the morning after the murder is to gloat, knowing full well that Helga will be horrified to know that Emily has just committed a crime to ensnare the real Miriam (Patricia Breslin), a florist who, for whatever reason, has made a devoted, lifelong enemy out of Emily. Miriam is the half-sister of Warren (Jean Arless), who's set to inherit their shared father's entire estate; and Miriam has a boyfriend named Karl (Glenn Corbett), a pharmacist. And that is all you get, because Homicidal is all complications and twists from the moment it hits the ground. It does enough to say that Emily 's hatred for Miriam and Helga and basically everything is deep-down nasty enough that she's hatched quite the scheme to take out all of them, and her relationship with Warren goes much beyond his hiring her to work as Helga's nurse, to the added detriment of all concerned.

The script's obscurity is a magic trick: it sets us up to look at the film as a confused messy B-picture, when in fact it's a puzzle designed so that once we triumphantly fit in the last piece, we're too proud of ourselves for having solved it to notice that we've gotten everything wrong. Of all the things Homicidal pilfers from Psycho - and there's virtually nothing in it that isn't either a direct lift or a mirror image of something in Joseph Stefano's script for that movie, right down to a psychiatrist explaining what the hell we just saw in the last moments - a twist ending that makes perfect sense even though the film has spent every molecule of oxygen directing you away from it is the one that makes me happiest.

It's also, as an added bonus, especially pleasant to look at. Castle's movies never suffer for style and atmosphere, though most of that comes from the sets he had to work with. In this case, he ended up with the most overqualified cinematographer he'd ever worked with, Burnett Guffey (who already had an Oscar and another nomination under his belt, and had more in his future), and together they give the film the suffocating texture of film noir mixed into the heightened naturalism and domesticity that was one of the newer trends in horror cinema of the time. It's a movie with a more striking appearance than should be possible for a minor production, but it gives the film such a personality that it was worth every wasted penny of Columbia's money: if for nothing else than a sublimely bleak nighttime exterior of the Hotel Ventura, and the stunning way an unexpectedly graphic decapitation is presented in the harshest contrast of light and shadow possible, Homicidal would be easily one of the best-looking movies of Castle's career, one of the best-looking horror B-pictures of the '50s or '60s, for that matter.

Throughout all of this, it's still basically a William Castle carnival: the surprisingly tricky writing, the style, the violence, all just ways of getting us whipped up to think more highly of an unabashedly shlocky cash-in. And the hell of it is, it works so well at doing so. It has flaws aplenty: the middle third is deathly slow and free of incident, and Breslin and Corbett provide no kind of energy whatsoever, on top of how it's all, basically, stupid. But the performances of Warren and Emily are so dynamic and unsettling - Warren especially, who feels unpleasantly "off" in a way I couldn't quite nail down at first, though it has to do with how his line deliveries don't feel quite right with his face - it gives the movie a nice blast of the exact half-goofy, half-terrifying energy that sets the film out as a Castle special.

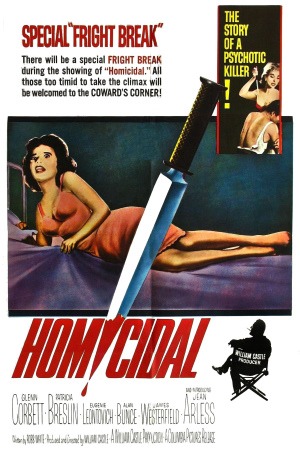

Especially when the gimmick comes in! We can't have a golden age Castle production without a gimmick! And in this case, it's a 45-second "fright break" that interrupts the movie at the 79-minute mark to flash a big stopwatch on the screen for any audience member too terrified to go on to leave the auditorium to receive a full refund. With the one caveat that they first have to be publicly pilloried by sitting in the Coward's Corner in the theater lobby, Castle's way of making sure that nobody actually took him up on that refund offer. It's not as obviously inspired as putting buzzers in theater seats or throwing a glowing skeleton at the audience, but it has the benefit of still being just as effective when you're watching the movie on TV at home, and can be baffled into blissful amusement by the producer/director's happy narration as he counts down the clock and urges all the scaredy cats in the audience to run on home like little chickens. It makes it entirely impossible to take the last eight minutes of the film, with their pile-up of revelations, even a little bit seriously, and that makes those revelations the most charming and fun part of the whole movie. As a result of this last-minute hucksterism, Homicidal has nothing resembling in even the most superficial way the rawness and power of its model, but damn me if it isn't still an excellent way to waste an hour and a half being thoroughly disconcerted by the horrible, cruel people parading across the screen.

Body Count: 3, only one of which is not exceptionally gory.

The savvy instinct is what led him to copy American cinema's biggest talking point of 1960, of course, but it's the enthusiasm that makes Homicidal such an appealing watch - certainly one of the best of the wannabe Psychos. It lacks the cheerful campiness of Castle's best-known films, The Tingler and House on Haunted Hill, both made in 1959 and both starring Vincent Price, patron saint of cheerful campiness. Indeed, besides the very opening and up until a key moment near the end, the film doesn't openly cop to any sense of humor at all, instead focusing sustaining its grim mystery and overall tension. Neither of those things are necessarily the film's best strength: William Castle was not, on his very best day, Alfred Hitchcock. But seeing the elements of Hitchcock as reworked by an aesthetic sensibility trained on matinee movies is a delight no matter what. Straitlaced as it undeniably is, Homicidal is shot through with a trashy glee in the things it can get away with.

It opens with its biggest single joke: Castle himself appears onscreen (as he tended to do) to introduce us to his latest masterwork, after briefly reminding us what some of his recent hits have been, all while calmly doing needlepoint. I love William Castle. And I love him all the more since the needlepoint he's been working on is the film's title, done in a homey font. From here, we head back to the past of the central family, one of the most fucked-up in any '60s film not based on the plays of Tennessee Williams. And we also head straight into the script's dogged refusal to clarify more than it absolutely has to, since all we see in the prologue is a little boy named Warren stealing a doll from a little girl whose name we never pick up, nor is their relationship clarified. Then we skip ahead to Ventura, CA: today. Not today. 1961 today. And here we find Miriam Webster (Joan Marshall), furtively checking into the Hotel Ventura with an obvious basketful of noir-heroine-on-the-run mystery, like we haven't just wandered into Psycho, we've skipped right ahead to the third reel. Miriam picks the youngest, handsomest bellhop (Richard Rust) to help her with the bags, and when she's got him alone in the room, she springs her highly abbreviated tale of woe: for the enormous sum of $2000, she'd like him to marry her, and get an annulment immediately. But they need to get married tonight. That kind of unthinkably large tip, plus the promise to hang around all evening with a beautiful woman, are enough to overcome his natural confusion at the situation, and late that night, they're on their way to a justice of the peace named Adrims (James Westerfield). No sooner has he completed the ceremony than Miriam pulls out a knife and stabs Adrims to death, fleeing before any of the witnesses or her dumbfounded new husband have had a chance to react.

That is just about as bravura as openings get: in terms of jaw-dropping madness per square inch and a desire to find out what the hell is going on, it's right up there with Samuel Fuller's crazed opening scene in The Naked Kiss. I can only imagine how it must have played in '61: the stabbing itself is magnificently disgusting, with squelchy stabbing noises that put the famed casaba melon of Psycho to shame, and while we never see the knife enter poor Adrims, the way he feebly paws at the spreading wet mass seeping into his shirt leaves even less to the imagination than the violence befalling Marion Crane in that doomed shower. The violence is shocking enough, in context (since even several decades later, anybody watching a William Castle picture isn't anticipating that kind of intense violence, and the director's joshing tone in the opening is hardly meant to give us an expectation of any kind of darkness to follow), that it even trumps how manifestly unclear anything in the plot is, to this point.

And, as it happens, as unclear as much of it remains. Homicidal is not a film bogged down by needless exposition, nor by much exposition at all, even down to the level of character relationships. We meet people, and we can tell that they're to be important down the line, but the film doesn't put much effort into clarifying why until it's actually important. So I'm not going to tell you how all of these people fit together: Miriam, it turns out, is actually a woman named Emily, and she's taking care of an elderly mute invalid, Helga (Eugenie Leontovich), whom she plainly doesn't like at all, given the first thing she does the morning after the murder is to gloat, knowing full well that Helga will be horrified to know that Emily has just committed a crime to ensnare the real Miriam (Patricia Breslin), a florist who, for whatever reason, has made a devoted, lifelong enemy out of Emily. Miriam is the half-sister of Warren (Jean Arless), who's set to inherit their shared father's entire estate; and Miriam has a boyfriend named Karl (Glenn Corbett), a pharmacist. And that is all you get, because Homicidal is all complications and twists from the moment it hits the ground. It does enough to say that Emily 's hatred for Miriam and Helga and basically everything is deep-down nasty enough that she's hatched quite the scheme to take out all of them, and her relationship with Warren goes much beyond his hiring her to work as Helga's nurse, to the added detriment of all concerned.

The script's obscurity is a magic trick: it sets us up to look at the film as a confused messy B-picture, when in fact it's a puzzle designed so that once we triumphantly fit in the last piece, we're too proud of ourselves for having solved it to notice that we've gotten everything wrong. Of all the things Homicidal pilfers from Psycho - and there's virtually nothing in it that isn't either a direct lift or a mirror image of something in Joseph Stefano's script for that movie, right down to a psychiatrist explaining what the hell we just saw in the last moments - a twist ending that makes perfect sense even though the film has spent every molecule of oxygen directing you away from it is the one that makes me happiest.

It's also, as an added bonus, especially pleasant to look at. Castle's movies never suffer for style and atmosphere, though most of that comes from the sets he had to work with. In this case, he ended up with the most overqualified cinematographer he'd ever worked with, Burnett Guffey (who already had an Oscar and another nomination under his belt, and had more in his future), and together they give the film the suffocating texture of film noir mixed into the heightened naturalism and domesticity that was one of the newer trends in horror cinema of the time. It's a movie with a more striking appearance than should be possible for a minor production, but it gives the film such a personality that it was worth every wasted penny of Columbia's money: if for nothing else than a sublimely bleak nighttime exterior of the Hotel Ventura, and the stunning way an unexpectedly graphic decapitation is presented in the harshest contrast of light and shadow possible, Homicidal would be easily one of the best-looking movies of Castle's career, one of the best-looking horror B-pictures of the '50s or '60s, for that matter.

Throughout all of this, it's still basically a William Castle carnival: the surprisingly tricky writing, the style, the violence, all just ways of getting us whipped up to think more highly of an unabashedly shlocky cash-in. And the hell of it is, it works so well at doing so. It has flaws aplenty: the middle third is deathly slow and free of incident, and Breslin and Corbett provide no kind of energy whatsoever, on top of how it's all, basically, stupid. But the performances of Warren and Emily are so dynamic and unsettling - Warren especially, who feels unpleasantly "off" in a way I couldn't quite nail down at first, though it has to do with how his line deliveries don't feel quite right with his face - it gives the movie a nice blast of the exact half-goofy, half-terrifying energy that sets the film out as a Castle special.

Especially when the gimmick comes in! We can't have a golden age Castle production without a gimmick! And in this case, it's a 45-second "fright break" that interrupts the movie at the 79-minute mark to flash a big stopwatch on the screen for any audience member too terrified to go on to leave the auditorium to receive a full refund. With the one caveat that they first have to be publicly pilloried by sitting in the Coward's Corner in the theater lobby, Castle's way of making sure that nobody actually took him up on that refund offer. It's not as obviously inspired as putting buzzers in theater seats or throwing a glowing skeleton at the audience, but it has the benefit of still being just as effective when you're watching the movie on TV at home, and can be baffled into blissful amusement by the producer/director's happy narration as he counts down the clock and urges all the scaredy cats in the audience to run on home like little chickens. It makes it entirely impossible to take the last eight minutes of the film, with their pile-up of revelations, even a little bit seriously, and that makes those revelations the most charming and fun part of the whole movie. As a result of this last-minute hucksterism, Homicidal has nothing resembling in even the most superficial way the rawness and power of its model, but damn me if it isn't still an excellent way to waste an hour and a half being thoroughly disconcerted by the horrible, cruel people parading across the screen.

Body Count: 3, only one of which is not exceptionally gory.

Categories: horror, mysteries, summer of blood, thrillers, william castle