Emus in the _le-de-France

The first image he told me about was of three children on a road in Iceland, in 1965. He said that for him, it was the image of happiness, and also that he had tried several times to link it to other images; but it never worked. He wrote me, 'One day, I'll have to put it all alone at the beginning of a film, with a long piece of black leader. If they don't see happiness in the picture, at least they'll see the black.'Until quite recently, my exposure to the pseudonymous French art film director Chris Marker - like most Americans' - consisted solely of his 1962 film La jetée, which - like most Americans - I watched in college.* Marker's films don't get much play in this country, sadly, and for a very long time they had precisely no presence on DVD.

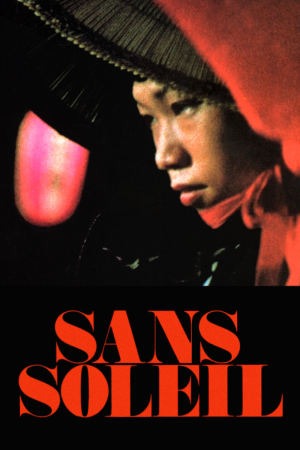

Now, happily, there is a sort of "Best of Marker" sampler on the market, combining La jetée with Sans soleil, his 1983...film, about...things.

It's taken me a while to write this. I watched Sans soleil pretty much blind last weekend, ready to review it, and it was...hard. Very hard. "I can't review this," I thought. So I decided that maybe it would be good to let it sit for a while, digest what the hell just happened, and above all, watch it a second time, and hope that maybe I could make heads or tails of it this time. As it turned out, the second viewing made it more inscrutable.

My response to Sans soleil is as particular and personal as any film I have ever watched. I think that I could watch it once a week until the day I die, coming up with new things to think about, getting confused about things that never bothered me, and altogether finding it a brilliant, encompassing experience. But damn me if I know how to put that into words.

Well, never let it be said that I wasn't willing to try.

First, it's probably best to explain what Sans soleil is. An unnamed woman (Florence Delay in the original French version, Alexandra Stewart in the English dub that I watched; Marker is very adamant that people watch his films in a language in which they are fluent, whenever possible) reads the letter of a sort of globe-trotting cinematographer, whose name, we learn in the end credits, is Sandor Krasna. Krasna has an obsession with using images to lock down his memories, and his letters to the woman serve to explicate what particular emotion he is trying and failing to express in any given image. His journeys take him primarily to Japan, and Cape Verde and Guinea-Bissau, with a startling detour to San Francisco, where he goes on a tour of the film locations of Alfred Hitchcock's Vertigo. He also includes footage of Iceland, but none of it was captured in the "now" of the film; it is from his trip there in 1965, and from a colleague's trip a few years later. Meanwhile, the woman alternates between simply reading the letters in the first person, and telling the audience in her own voice what the letters say, and what she made of them.

Reading over what I just wrote, I am surprised by how essentially accurate it is, and how totally it fails to capture anything essential about the film, whatsoever.

Self-evidently, I know there's not a "key" to this film, but that doesn't mean that I'll pass up an obvious signpost when I come across it, and that means that the easiest place to begin is with the Hitchcock film. It's hard to explain how weird it feels when Marker/Krasna/the woman abruptly stops discussing the society and politics of Japan and West Africa, and launches into a bit of film theory, but it's the sort of moment that stands out too erratically from the fairly uniform whole behind it, to be regarded as mere accident or whim. Marker clearly wants us to notice that he, or Krasna (I'll stop doing that, I promise, but I think it's extraordinarily important to notice that there are three distinct voices narrating Sans soleil - the director, his fictional cameraman, and the woman - and at any given moment it's pretty much impossible, as far as I can tell, to know who is the auteur), has a fixation on Vertigo, of all movies.

What is Vertigo? Happily, the film provides its own answer, one that hardly counts as a comprehensive reading, but certainly not one that any reasonable person could disagree with. Vertigo, we are shown, is a film about the destructive nature, unto rapaciousness, of memory. It's not a story of the past intruding on the present, so much as it is a story of the past brought into the present kicking and screaming, and ending multiple lives in the process. I'm not sure that I'd claim that Sans soleil is so nihilistic as to argue that the earlier film is about the danger of knowing the past, but it comes awfully close to that claim.

It would be impossible to watch Marker's film without noticing that it has a fixation on capturing the past in a concrete form - something that Krasna is mostly pessimistic about being able to do, even though it is the sole justification he ever offers for explicating his images to the woman - but only in the Vertigo sequence are we explicitly told that this can be a destructive tendency. Perhaps Krasna's recognition of the futility of his project is a sort of halfway recognition of that fact, that taking an image and saying "this is the past; this is my memory" means nothing, and that assuming that an image is the truth is the act of a fool (he states this multiple times in varying degrees of specificity; the most memorable example, to me, is when he shows footage of an African general cheerfully receiving a commendation, as the woman matter-of-factly tells how Krasna realised, years later, that the general was even then planning a coup against the very president pinning a medal on his chest).

This ambivalence about the quality of images bleeds into the element that is surely the strangest part of Sans soleil: its continual return to the digital imaging software of (fictive) Japanese computer scientist Hayao Yamaneko, who we are told spends all his free time running film footage into a machine that turns them into brightly-duochromatic, flat images that can barely be recognized. Some combination of Yamaneko, Krasna and Marker describes this altered footage as "The Zone," and two viewings in, I'm still not sure what that means. What I do know is that the purpose of The Zone is to deconstruct the image from its meaning. By apparently "destroying" the image, by rendering it almost unrecognizable, Yamaneko actually saves the image, by removing the false referent, the memory, that is neither described by the image, nor explains what the image means.

This epiphany is not complete, however, for late in the film, Krasna finally discovers the perfect way to bring meaning out of his most treasured bit of footage: three children walking on a road in Iceland in 1965, the image of pure and naïve happiness. This footage, which Krasna finally perfects, is never subject to The Zone; it is kept as a pristine record of a subjective memory.

Watching Sans soleil is a bit like being exposed to someone else's dream without being allowed to share it; it has the texture of an hallucination, more than anything. But it is a structured hallucination, with a clear emotional journey, albeit one whose content changes, I think, from viewer to viewer and viewing to viewing. Really, it's not like a "movie," it's more like a symphony, with repeating motifs throughout that change value based on context, discrete movements that share elements with each other, and most importantly, theme and emotion that are in the viewer without mediation. Sans soleil is more intuitive than rational, and that makes it a singular, overpowering experience.

*Yes, "most Americans.: Please don't correct me.