Dangerous invasions

Don Siegel is one of the great American auteurs that nobody ever really thinks about. Partly, I suppose this is because his most famous film is Pauline Kael's favorite fascist cop movie, Dirty Harry, and nobody really wants to be a Dirty Harry apologist. (Edited to add: Years later, most of those claims are no longer true, if indeed they ever were).

That doesn't change the fact that Siegel left behind him a pretty damn solid body of work, linked perhaps more by theme than by technique, but still unmistakably the product of a man with a consistent worldview: the highest respect reserved for the rugged individuals who buck the system, whatever "bucking the system" means in a given context.

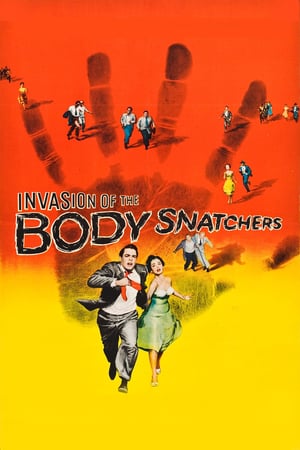

It's my contention that this belief is at the core of the notoriously tetchy politics of the 1956 Invasion of the Body Snatchers, a film made well into Siegel's career but probably his first work that still carries any sort of reputation. By this point it's not anything other than a cliché to observe that science fiction in the 1950s was more obsessed with social commentary than at perhaps any other point in the genre's history, and even within that context, the original Invasion is pretty unsubtly allegorical; but what the hell that allegory means, exactly, is the subject of much debate.

I hope you're familiar with at least the raw outline of the plot: a bucolic California town is suffering from what an epidemic, as more and more residents of the tight-knit community become convinced, to the point of near-insanity, that their friends and loved ones aren't who they seem to be. At first, the Sensible People (embodied in this version by Dr. Miles Bennell) scoff at this paranoia, but it becomes obvious that something is not quite right in the world, and then it becomes obvious that "something" in this case means "large alien seed pods that turn into clones of human beings with all the memories but none of the emotions intact."

Broadly, there are two ways that this has been read: the pods are Communists, which fits the plot specifics well, or the pods are McCarthyists, which fits the film's general snarky tone against suburban Americana well (for the record, Siegel claimed that he intended no such themes, which proves once again that artists can't interpret their own work). Some people argue that it's about "both," which is almost what I believe; but I'm happier saying that it's about "neither."

Instead, I think it's a cautionary tale about letting people do your thinking for you: in other words, an anti-conformity tale, and while that includes both anti-Communist and anti-anti-Communist themes, it includes a whole lot more than that, too. It's easy to lack back on the 1950s from our lofty historical perspective, and feel haughty about our comparative sophistication: we are not such white-bread milquetoasts! We are not afraid of our own shadows! Etc.

Like everything else, the truth is much more interesting than that. Sure, there was a lot of stress on "normal American living" in the 1950s (when isn't there?), but there were plenty of people bent on mocking that mentality (when aren't there?).

All great horror...and yes, I recognise the danger of starting a sentence with "all great" anything...all great horror starts by showing us a peaceful, even ideal situation, into which a terrible, destructive, alien force intrudes, destroying the peacefulness. Invasion of the Body Snatchers is surely a great horror film. The first 25 of its 80 minutes are dedicated to nothing but the establishment of the wonderful little small town where everybody knows everybody else, and the remainder is focused on watching that wonderful little small town die.

By focusing on the fragility of the idealised suburban life, the film argues against the simple mentality of "I will do what other people think is right" that leads to all authoritarianism, and was such an important part of the appearance, if not the reality, of the post-war era. There's no particular conservative or socialist bent to any of that: it's a film about not letting other people do your thinking, period.

So much for theme.

The film qua the film is extraordinary, one of the very best sci-fi/horror pictures of one of that genre's best decades. Its 80 minutes are essentially flawless: by the standards of cheapo b-pictures, that's not a particularly short running time, but it seems impossibly brief to the modern eye, and the film absolutely flies past, without a single moment of fat. Although there's not much plot in the early going, the attention paid to character and setting is extremely efficient and valuable. The film has a very quiet sarcasm about it, that bleeds into its later themes, in which the "perfect" face of the community hides secrets and lies: my particular favorite moment is the smiling use of "a trip to Reno" as a euphemism for divorce, in a society that views such things as unmentionable.

Once the plot kicks in, the ride begins in earnest, and although most of what happens is just a variation on two people hiding and running, it's extraordinarily exciting and even frightening (which is not a word that you get to use about '50s horror, like, ever). This is where Siegel and his under-appreciated talents come into play. He's a great director of tension, which is an odd thing to say, but the ability to drag a moment out for its maximum effect without killing the scene's momentum is quite rare.

Most of the tension in Invasion comes from the simple matter of not quite knowing where things are, which in turn comes from a lighting scheme that bears a strong debt to the contemporaneous films noirs. Really, it's almost barbarically simple: in the early part of the movie, there are many bright outdoorsy scenes, and later on there are almost nothing but night scenes, and even the interiors are usually lit so as to make the shadows just as prevalent as the patches of light. The dark is dangerous in film, and in Invasion the dark is everywhere, around and ultimately inside our homes. This is made all the stronger by the connection between sleeping and death: it's only when you sleep that the pods can take over your body, and this turns perhaps the most intimate and personal of all human actions into the most dangerous. This is smashingly effective horror, turning those things that give us strength - home and community - into deadly traps.

Which is ordinarily where I'd leave things, but I have to say a word in praise of Kevin McCarthy, a character actor of no particular notice who plays Dr. Bennell. The '50s were a decade of square jaws and manly heroes, almost comically, so, and McCarthy is frankly, a little soft and schlubby. Of course, he's got more movie-star good looks than 90% of the real world, but that's still pretty dull-looking by Hollywood standards. Because of that, he is a more believable Everyman than just about any hero I can think of from any other film of the same era, and when paired with a mostly good performance - he's not so good at doing anything but the paranoia, but given how important that is, especially in the rather bleak final five minutes, it doesn't feel like too big of a liability that he can't do the love story so much - he stands out as one of the most believably human protagonists of any 1950s b-movie I can name.

That doesn't change the fact that Siegel left behind him a pretty damn solid body of work, linked perhaps more by theme than by technique, but still unmistakably the product of a man with a consistent worldview: the highest respect reserved for the rugged individuals who buck the system, whatever "bucking the system" means in a given context.

It's my contention that this belief is at the core of the notoriously tetchy politics of the 1956 Invasion of the Body Snatchers, a film made well into Siegel's career but probably his first work that still carries any sort of reputation. By this point it's not anything other than a cliché to observe that science fiction in the 1950s was more obsessed with social commentary than at perhaps any other point in the genre's history, and even within that context, the original Invasion is pretty unsubtly allegorical; but what the hell that allegory means, exactly, is the subject of much debate.

I hope you're familiar with at least the raw outline of the plot: a bucolic California town is suffering from what an epidemic, as more and more residents of the tight-knit community become convinced, to the point of near-insanity, that their friends and loved ones aren't who they seem to be. At first, the Sensible People (embodied in this version by Dr. Miles Bennell) scoff at this paranoia, but it becomes obvious that something is not quite right in the world, and then it becomes obvious that "something" in this case means "large alien seed pods that turn into clones of human beings with all the memories but none of the emotions intact."

Broadly, there are two ways that this has been read: the pods are Communists, which fits the plot specifics well, or the pods are McCarthyists, which fits the film's general snarky tone against suburban Americana well (for the record, Siegel claimed that he intended no such themes, which proves once again that artists can't interpret their own work). Some people argue that it's about "both," which is almost what I believe; but I'm happier saying that it's about "neither."

Instead, I think it's a cautionary tale about letting people do your thinking for you: in other words, an anti-conformity tale, and while that includes both anti-Communist and anti-anti-Communist themes, it includes a whole lot more than that, too. It's easy to lack back on the 1950s from our lofty historical perspective, and feel haughty about our comparative sophistication: we are not such white-bread milquetoasts! We are not afraid of our own shadows! Etc.

Like everything else, the truth is much more interesting than that. Sure, there was a lot of stress on "normal American living" in the 1950s (when isn't there?), but there were plenty of people bent on mocking that mentality (when aren't there?).

All great horror...and yes, I recognise the danger of starting a sentence with "all great" anything...all great horror starts by showing us a peaceful, even ideal situation, into which a terrible, destructive, alien force intrudes, destroying the peacefulness. Invasion of the Body Snatchers is surely a great horror film. The first 25 of its 80 minutes are dedicated to nothing but the establishment of the wonderful little small town where everybody knows everybody else, and the remainder is focused on watching that wonderful little small town die.

By focusing on the fragility of the idealised suburban life, the film argues against the simple mentality of "I will do what other people think is right" that leads to all authoritarianism, and was such an important part of the appearance, if not the reality, of the post-war era. There's no particular conservative or socialist bent to any of that: it's a film about not letting other people do your thinking, period.

So much for theme.

The film qua the film is extraordinary, one of the very best sci-fi/horror pictures of one of that genre's best decades. Its 80 minutes are essentially flawless: by the standards of cheapo b-pictures, that's not a particularly short running time, but it seems impossibly brief to the modern eye, and the film absolutely flies past, without a single moment of fat. Although there's not much plot in the early going, the attention paid to character and setting is extremely efficient and valuable. The film has a very quiet sarcasm about it, that bleeds into its later themes, in which the "perfect" face of the community hides secrets and lies: my particular favorite moment is the smiling use of "a trip to Reno" as a euphemism for divorce, in a society that views such things as unmentionable.

Once the plot kicks in, the ride begins in earnest, and although most of what happens is just a variation on two people hiding and running, it's extraordinarily exciting and even frightening (which is not a word that you get to use about '50s horror, like, ever). This is where Siegel and his under-appreciated talents come into play. He's a great director of tension, which is an odd thing to say, but the ability to drag a moment out for its maximum effect without killing the scene's momentum is quite rare.

Most of the tension in Invasion comes from the simple matter of not quite knowing where things are, which in turn comes from a lighting scheme that bears a strong debt to the contemporaneous films noirs. Really, it's almost barbarically simple: in the early part of the movie, there are many bright outdoorsy scenes, and later on there are almost nothing but night scenes, and even the interiors are usually lit so as to make the shadows just as prevalent as the patches of light. The dark is dangerous in film, and in Invasion the dark is everywhere, around and ultimately inside our homes. This is made all the stronger by the connection between sleeping and death: it's only when you sleep that the pods can take over your body, and this turns perhaps the most intimate and personal of all human actions into the most dangerous. This is smashingly effective horror, turning those things that give us strength - home and community - into deadly traps.

Which is ordinarily where I'd leave things, but I have to say a word in praise of Kevin McCarthy, a character actor of no particular notice who plays Dr. Bennell. The '50s were a decade of square jaws and manly heroes, almost comically, so, and McCarthy is frankly, a little soft and schlubby. Of course, he's got more movie-star good looks than 90% of the real world, but that's still pretty dull-looking by Hollywood standards. Because of that, he is a more believable Everyman than just about any hero I can think of from any other film of the same era, and when paired with a mostly good performance - he's not so good at doing anything but the paranoia, but given how important that is, especially in the rather bleak final five minutes, it doesn't feel like too big of a liability that he can't do the love story so much - he stands out as one of the most believably human protagonists of any 1950s b-movie I can name.