The 43rd Chicago International Film Festival

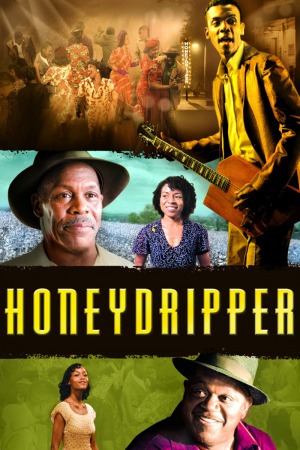

The Aughts have not been kind to the once-mighty John Sayles. From the winking screenplays for Piranha and The Howling to his directorial work including an extraordinary 12-year run from Matewan to Limbo, it really did seem like he was incapable of making movies that weren't at least interesting, when they weren't outright masterpieces. But since the turn of the millennium, he has only been able to muster up Sunshine State, Casa de los Babys and Silver City in quick succession, three flat and lifeless wastes of talented ensembles and a once-incisive eye for the nuances of communities. Now, three years after the last of those, he comes back with Honeydripper: by all means a fine film, by no means a great film, but good enough next to his meager recent output that it seems much closer to being a masterpiece than is objectively the case.

The film is set in 1950, in Harmony, Alabama, a town whose ironic and metaphorical name is commented upon at its first appearance and so becomes much less arch in both its irony and metaphor. Tyrone "Pinetop" Purvis (Danny Glover) is the owner of the Honeydripper Lounge, an old-time blues shack fallen on hard times due to the new rhythm & blues place across the way. In debt to everyone under the sun, Tyrone hits upon the desperate gamble of inviting Guitar Sam of New Orleans to play for one night, and pray that the night's profits will be enough to cover his food and liquor and rent expenses for just one more month.

The plot is mostly incidental to two much better trends: first is the languid ease with which Sayles introduces his typically capable ensemble, made of up some fantastic character actors and various blues legends who've never "acted" before: the latter group including such insufficiently famous names as Eddie Shaw, Keb' Mo' and Mable John (whose brief turn as the ousted featured star of the Honeydripper is perhaps the most arresting and electrifying part of the film), the former including Charles S. Dutton, Vondie Curtis Hall, Lisa Gay Hamilton and rather surprisingly, Yaya DaCosta, giving the single finest performance by far ever recorded by a former America's Next Top Model contestant, but I didn't really say that, because that would be embarrassing.

Second is the film's preoccupation with the crucible in which "the blues" became "rhythm and blues" became "rock and roll." It's pretty obvious that Sayles loves all three (and why not, his CV includes videos for Springsteen's "Born in the U.S.A." and "Glory Days," rock anthems if ever there were),* going so far as to write the songs featured in the film his very own self. And I think you'd be hard pressed to argue that the scenes involving musical performances, be they rock, blues or gospel, aren't the best parts of the movie, and it would be much enriched if there were more of them.

Sayles has never been a wildly stylistic director, but he certainly knows his way around a camera (that, and he works with awfully good cinematographers a lot: most frequently Haskell Wexler, but also Robert Richardson and Slawomir Idziak. Dick Pope does the honors here). Still, Honeydripper has a distinct lack of visual panache that is at least partially motivated by its content, which is summery and laid-back, although that doesn't keep it from being disheartening. Sayles's camera is unusually passive here: it's soaking in visuals without engaging with them, and except for a few scenes inside the Honeydripper itself, there aren't many moments that don't feel essentially flat. There's always a wall of sorts between the camera and the action, which is a great shame: at his best, Sayles is uncannily good at capturing the tenor of a community but here we're mostly sitting back and watching.

That leaves most of the heavy lifting up to the actors, and while this particular director has always been fond of that gambit (in a good way), here he is perhaps too hands-off (still, he doesn't actively sabotage their efforts, which is a good shift from his last three projects). So it's a good thing that the cast is especially strong, anchored by Glover, who at the age of 61 gives the fullest performance of his mostly-distinguished career, carrying himself with a blend of desperation and canniness that never tips too far in either direction. He's surround by plenty of great support: Dutton as his right-hand man is more playful and thoughtful than I've ever seen him, and Hamilton is more of everything than I would have assumed she had in her to give, particularly in her scenes at a revivalist's tent, where the curve of her mouth communicates more than whole pages of screenplay could even stab at. Et cetera ad infinitum; I'm not going through every performer, there's a frightening number of them, and they're all at least quite good.

When all is said and done it doesn't add up to a whole lot, but at least it's fun, and it seems that's all that Sayles had in mind. This is what we call a "minor" film: not much of the theme, less of the technique, but surely not a waste of anyone's time or effort. It's a tiny delight.

7/10

Kudos, by the way, to Sayles and his self-distribution model that is likely to screw the film over rather badly, but serves to remind me of all the reasons that I decided 8 years ago that I wanted to be him when I grew up.

The film is set in 1950, in Harmony, Alabama, a town whose ironic and metaphorical name is commented upon at its first appearance and so becomes much less arch in both its irony and metaphor. Tyrone "Pinetop" Purvis (Danny Glover) is the owner of the Honeydripper Lounge, an old-time blues shack fallen on hard times due to the new rhythm & blues place across the way. In debt to everyone under the sun, Tyrone hits upon the desperate gamble of inviting Guitar Sam of New Orleans to play for one night, and pray that the night's profits will be enough to cover his food and liquor and rent expenses for just one more month.

The plot is mostly incidental to two much better trends: first is the languid ease with which Sayles introduces his typically capable ensemble, made of up some fantastic character actors and various blues legends who've never "acted" before: the latter group including such insufficiently famous names as Eddie Shaw, Keb' Mo' and Mable John (whose brief turn as the ousted featured star of the Honeydripper is perhaps the most arresting and electrifying part of the film), the former including Charles S. Dutton, Vondie Curtis Hall, Lisa Gay Hamilton and rather surprisingly, Yaya DaCosta, giving the single finest performance by far ever recorded by a former America's Next Top Model contestant, but I didn't really say that, because that would be embarrassing.

Second is the film's preoccupation with the crucible in which "the blues" became "rhythm and blues" became "rock and roll." It's pretty obvious that Sayles loves all three (and why not, his CV includes videos for Springsteen's "Born in the U.S.A." and "Glory Days," rock anthems if ever there were),* going so far as to write the songs featured in the film his very own self. And I think you'd be hard pressed to argue that the scenes involving musical performances, be they rock, blues or gospel, aren't the best parts of the movie, and it would be much enriched if there were more of them.

Sayles has never been a wildly stylistic director, but he certainly knows his way around a camera (that, and he works with awfully good cinematographers a lot: most frequently Haskell Wexler, but also Robert Richardson and Slawomir Idziak. Dick Pope does the honors here). Still, Honeydripper has a distinct lack of visual panache that is at least partially motivated by its content, which is summery and laid-back, although that doesn't keep it from being disheartening. Sayles's camera is unusually passive here: it's soaking in visuals without engaging with them, and except for a few scenes inside the Honeydripper itself, there aren't many moments that don't feel essentially flat. There's always a wall of sorts between the camera and the action, which is a great shame: at his best, Sayles is uncannily good at capturing the tenor of a community but here we're mostly sitting back and watching.

That leaves most of the heavy lifting up to the actors, and while this particular director has always been fond of that gambit (in a good way), here he is perhaps too hands-off (still, he doesn't actively sabotage their efforts, which is a good shift from his last three projects). So it's a good thing that the cast is especially strong, anchored by Glover, who at the age of 61 gives the fullest performance of his mostly-distinguished career, carrying himself with a blend of desperation and canniness that never tips too far in either direction. He's surround by plenty of great support: Dutton as his right-hand man is more playful and thoughtful than I've ever seen him, and Hamilton is more of everything than I would have assumed she had in her to give, particularly in her scenes at a revivalist's tent, where the curve of her mouth communicates more than whole pages of screenplay could even stab at. Et cetera ad infinitum; I'm not going through every performer, there's a frightening number of them, and they're all at least quite good.

When all is said and done it doesn't add up to a whole lot, but at least it's fun, and it seems that's all that Sayles had in mind. This is what we call a "minor" film: not much of the theme, less of the technique, but surely not a waste of anyone's time or effort. It's a tiny delight.

7/10

Kudos, by the way, to Sayles and his self-distribution model that is likely to screw the film over rather badly, but serves to remind me of all the reasons that I decided 8 years ago that I wanted to be him when I grew up.