The chill of ghostly shadows

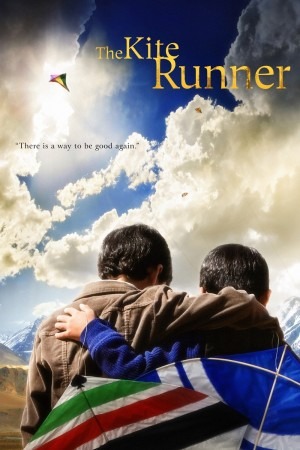

The Kite Runner is everything that I think of when I haughtily trot out the phrase "middlebrow art film". It is based on a popular book that is probably not quite good enough to justify its popularity. It is about Significant Themes That Matter Today. It is not very happy, but traditional morality is safely upheld when all is said and done. It tells the audience what to feel and is never, ever challenging in any way. Most damningly, it is directed by Marc Forster, a name that should strike icy fear into the hearts of all those who love cinema as an art form, and not a bourgeois popular entertainment. So mighty indeed is my instinctive fear of the man and his determinedly anonymous filmmaking style, I think I need to try this again: it is directed by Marc Forster.

The Kite Runner begins in San Francisco in the year 2000, before flashing back to Kabul, Afghanistan in the 1970s. Here we meet Amir (Zekeria Ebrahimi), a spoiled child of wealth, and Hassan (Ahmad Khan Mahmidzada), the son of Amir's father's servant and a member of the despised Hazara ethnic group. The two boys are close friends, as close as can be given Amir's nascent classism, and life is all play and kite-flying and vaguely threatening childlike one-upsmanship, until a terrible thing happens that drives Amir to hate all his own cowardice and entitlement that he sees whenever he looks at Hassan.

Jump a few years, to see Amir (now played by Khalid Abdalla) and his father making a life for themselves in California, having fled Afghanistan during the Russian invasion. As such things will happen, Amir falls in love with fellow emigré Soraya (Atossa Leoni) and they wed. Jump a few more years, to 2000 again, as Amir learns that he can finally atone for the terrible things he did to Hassan, but it will require him to return to Afghanistan and confront a past he'd be much happier leaving buried.

Hollywood films being what they are, and Marc Forster being who he is, it didn't really surprise me very much that everything good about the book has been removed from the film, and everything trite and unconvincing in the book has been left as the core of the drama. What Khaled Hosseini's debut novel does best is to function as a sort of diary; particularly in the opening third, detailing Amir and Hassan's day-to-day world. It's easy to reduce it to "oh, it's interesting because it normalises Afghanistan," but that misses the point. It's a study of childhood set in a place very few of us would otherwise know about, but it's far more interesting as psychology than sociology. And all of it gets cut in a headlong rush to move the plot along quickly, shedding all the rich little details of life that made the book fascinating. What the novel does next best is to flesh out the ways in which Amir, at all stages of life, feels crushed under his father's rigid views of masculine behavior, views that don't account for Amir's shyness and anxiety and literary ambitions. Except for a few random lines of dialogue here and there, that all gets cut too.

What stays is the bland central plot, in which a child is crudely used as the symbol of a man's redemption and a cardboard villain who invokes Nazism is trotted out for our self-righteous booing and hissing before he's roundly beaten in a sop to the bloodthirsty. In the meantime, Forster and his screenwriter David Benioff capture all of the notes but none of the melodies of the book: showing us the life of Afghanis pre- and post-diaspora without any sort of context to make them anything other than people in funny clothes spouting banal dialogue.

But the film's chief sin isn't its script. It's chief sin is the expressionless visual language, a brightly shined-up and award-ready adventure in making a movie completely without niceness. There is not a shot nor a transition that isn't the least-imaginative choice at any given moment. This is of course the chief characteristic of Marc Forster's cinema, and yet I think The Kite Runner may be the most graceless film of his career, even after Stranger than Fiction suggested in a stumbling, faltering way that he might have some fledgling idea how to relate the dramatic and the visual. Forster has always dedicated himself to the pursuit of the tastefully neutral, and here is his apotheosis: a potboiler about Middle Eastern identity and politics that looks as flat and fastidious as a student film shot in Griffith Park. It lacks any urgency or heft, and has the emotional resonance of belly button lint.

It wouldn't be right to go without admitting that the one great thing about the movie, Homayoun Ershadi's performance as Amir's father. Ershadi is most famous for his debut film, Abbas Kiarostami's Taste of Cherry, which proved that he could act; his work in this film, although hampered by the gutting of the character's meanness, is absolutely top-notch work, bringing back some of the imperiousness that the script ignores and engendering a sort of reflexive fear and respect for his patriarchal authority. He gives a great performance in search of a film worthy of his intensity.

As for the rest: boilerplate mediocrity. Forster and Benioff are clearly laboring under the belief that making a film about children learning unhappy truths automatically makes for compelling drama and setting a film in an Islamic country automatically makes for sober-minded political significance. They are wrong. All The Kite Runner proves is that aggressively unexceptional filmmaking skills make for aggressively unexceptional films.

4/10

The Kite Runner begins in San Francisco in the year 2000, before flashing back to Kabul, Afghanistan in the 1970s. Here we meet Amir (Zekeria Ebrahimi), a spoiled child of wealth, and Hassan (Ahmad Khan Mahmidzada), the son of Amir's father's servant and a member of the despised Hazara ethnic group. The two boys are close friends, as close as can be given Amir's nascent classism, and life is all play and kite-flying and vaguely threatening childlike one-upsmanship, until a terrible thing happens that drives Amir to hate all his own cowardice and entitlement that he sees whenever he looks at Hassan.

Jump a few years, to see Amir (now played by Khalid Abdalla) and his father making a life for themselves in California, having fled Afghanistan during the Russian invasion. As such things will happen, Amir falls in love with fellow emigré Soraya (Atossa Leoni) and they wed. Jump a few more years, to 2000 again, as Amir learns that he can finally atone for the terrible things he did to Hassan, but it will require him to return to Afghanistan and confront a past he'd be much happier leaving buried.

Hollywood films being what they are, and Marc Forster being who he is, it didn't really surprise me very much that everything good about the book has been removed from the film, and everything trite and unconvincing in the book has been left as the core of the drama. What Khaled Hosseini's debut novel does best is to function as a sort of diary; particularly in the opening third, detailing Amir and Hassan's day-to-day world. It's easy to reduce it to "oh, it's interesting because it normalises Afghanistan," but that misses the point. It's a study of childhood set in a place very few of us would otherwise know about, but it's far more interesting as psychology than sociology. And all of it gets cut in a headlong rush to move the plot along quickly, shedding all the rich little details of life that made the book fascinating. What the novel does next best is to flesh out the ways in which Amir, at all stages of life, feels crushed under his father's rigid views of masculine behavior, views that don't account for Amir's shyness and anxiety and literary ambitions. Except for a few random lines of dialogue here and there, that all gets cut too.

What stays is the bland central plot, in which a child is crudely used as the symbol of a man's redemption and a cardboard villain who invokes Nazism is trotted out for our self-righteous booing and hissing before he's roundly beaten in a sop to the bloodthirsty. In the meantime, Forster and his screenwriter David Benioff capture all of the notes but none of the melodies of the book: showing us the life of Afghanis pre- and post-diaspora without any sort of context to make them anything other than people in funny clothes spouting banal dialogue.

But the film's chief sin isn't its script. It's chief sin is the expressionless visual language, a brightly shined-up and award-ready adventure in making a movie completely without niceness. There is not a shot nor a transition that isn't the least-imaginative choice at any given moment. This is of course the chief characteristic of Marc Forster's cinema, and yet I think The Kite Runner may be the most graceless film of his career, even after Stranger than Fiction suggested in a stumbling, faltering way that he might have some fledgling idea how to relate the dramatic and the visual. Forster has always dedicated himself to the pursuit of the tastefully neutral, and here is his apotheosis: a potboiler about Middle Eastern identity and politics that looks as flat and fastidious as a student film shot in Griffith Park. It lacks any urgency or heft, and has the emotional resonance of belly button lint.

It wouldn't be right to go without admitting that the one great thing about the movie, Homayoun Ershadi's performance as Amir's father. Ershadi is most famous for his debut film, Abbas Kiarostami's Taste of Cherry, which proved that he could act; his work in this film, although hampered by the gutting of the character's meanness, is absolutely top-notch work, bringing back some of the imperiousness that the script ignores and engendering a sort of reflexive fear and respect for his patriarchal authority. He gives a great performance in search of a film worthy of his intensity.

As for the rest: boilerplate mediocrity. Forster and Benioff are clearly laboring under the belief that making a film about children learning unhappy truths automatically makes for compelling drama and setting a film in an Islamic country automatically makes for sober-minded political significance. They are wrong. All The Kite Runner proves is that aggressively unexceptional filmmaking skills make for aggressively unexceptional films.

4/10