There was a time in this fair land when the railroad did not run

Four years after arriving at Fox with Just Pals, Jack Ford had begun to call himself "John," to go along with the much more serious dramas that he'd begun directing for William Fox. The young director, not yet thirty years old, was on the very verge of greatness, and the studio mogul started to formulate the idea that Ford's starmaking feature (as it were) should be the most prestigious film the studio could manage - in 1923, Fox was releasing cheap programmers and steadily losing market share, and the hope was that in one fell swoop, a studio would be rejuvenated and a career would be born.

At about this time, Paramount had turned a vast profit on a terribly expensive Western directed by the long-forgotten James Cruze, The Covered Wagon. It cost an extravagant $782,000 but returned an estimated $3.8 million, and Hollywood being Hollywood even in the mid-'20s (especially in the mid-'20s), it seemed like the smartest move in the world would be to sink a huge budget into an epic Western, and stand back as the money came gushing back.

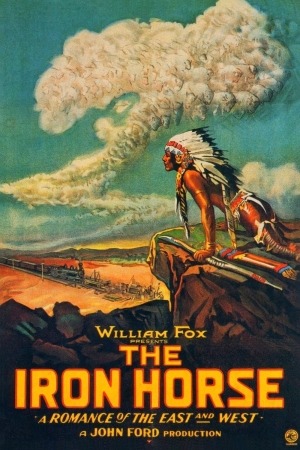

Thus it was that William Fox came to produce The Iron Horse, a panoramic retelling of the quest to build the transcontinental railroad in the aftermath of the Civil War. John Ford was given more or less free reign to make the film, and that is just what he did, going weeks over schedule and thousands of dollars over budget; ultimately, the $450,000 film returned over $2 million, catapulting the Fox studio to the front echelons of Hollywood and transforming Ford instantly into one of the hottest artists in the industry.

The latter, part, at least, is surely deserved - as with most sufficiently epic-scale movies, it's hard to credit the considerable of The Iron Horse to anyone other than the director. It was Ford, after all, who insisted on taking the whole damn shoot out of Los Angeles, making the first film in American history to be shot in its entirety so far from any center of production. The filmmakers set up camp - "Camp Ford," the not-so-small community was called - in the center of the Nevada desert, where Ford set up a Kurtz-like dictatorship where his word was law and the infrequent missives from the studio were ignored as a matter of course. In this we see the first glimmer of a man whose lionisation of Monument Valley would establish him as the greatest on-location filmmaker that this country would ever know.

As a narrative, The Iron Horse looks awfully familar to the modern eye, because we see very similar films nearly every autumn. Though the Academy Awards would not exist for another four years, and Oscarbaiting for another five, it's hard to shake the feeling that The Iron Horse follows a very standard formula for awards season prestige pictures: it is about a major historic event, it seeks to reassure the audience rather than challenge them, it mixes fact with an elementally simple love story, and it even has performances that consist of very little other than looking as much as possible like a famous person. Is it irresponsible to speculate that John Ford invented the prestige epic? It is irresponsible not to.

Opening in Springfield, IL what we can safely call "around the1840s," the film centers less around a character than a process that begins when David Brandon (James Gordon) departs the settled Midwest to pursue his dream of finding a route to run rail lines all the way to California. His ideas are treated as sheer crackpottery by his neighbor Thomas Marsh (Will Walling), but his other neighbor, a lanky gent named Abe Lincoln (Charles Edward Bull) isn't so dismissive. Unfortunately, Brandon has hardly arrived in Cheyenne country when he and his son Davy (Winston Miller) are ambushed by a hunting party led by a white man with two fingers on his right hand. As the son watches from his hiding place, the father is beaten and scalped. The viewer is reminded that in 1924, there was none of this "production code" nonsense.

In 1862, Congress passes a bill that President Lincoln signs into law, authorising the construction of a railroad between Council Bluffs, IA and Sacramento, CA. The overseer of this project is none other than Thomas Marsh, who brings along his daughter Miriam (Madge Bellamy) and her much older fiancé, Marsh's assistant Jesson (Cyril Chadwick) to the site of construction near Omaha, NE. There, we find much in the way of frontier life, containing a sprawling cast of colorful figures, although the most important are Deroux (Fred Kohler), an Eevil Landowner, and Davy Brandon, all growed up and played by George O'Brien, then at the very start of his career as Fox's favorite leading man of the late silent era (he would eventually play the male lead in Sunrise, the finest thing William Fox ever touched). Scenes of Miriam torn between her childhood sweetheart and her dull fiancé alternate with rowdy Western comedy and passages that inspirationally recreate the great engineering triumph of the mid-19th Century. Scenes are also interspersed of clichéd Savage Indians, which I wouldn't ordinarily complain about - devaluing 80-year-old films because of racism offends my sense of art history - but it's surprising, given that even when they don't obviously seem like it, Ford's later films all have at least some nuance to their depiction of Native Americans.

In many ways, The Iron Horse is an archetypal John Ford film. Here we finally see the director using the power of landscape to provide a framework for his narrative - something like what Werner Herzog would later call the "voodoo of location." Here is the easy contrast between comedy and melodrama and action that would become a Ford trademark. Here is the comically (but lovingly!) overdone Irishman that would prove to be a stable of Ford's comic relief. And here, more than everything else, is the striking patriotism and love of Americana that would later wind its way through most of the director's films, however subtly.

For example, Abraham Lincoln. 15 years down the road, Ford would direct Henry Fonda for the first time in Young Mr. Lincoln, cementing his obvious love for the 16th president. The Iron Horse is something like a dry run of that theme; Lincoln hardly appears in the film for five minutes (although within those five minutes, Bull gives the most restrained and effective performance in the whole picture), but his presence haunts every moment, from the opening card (over Lincoln's bust) to the close (also over Lincoln's bust). It feels something like the country would see again in the 1960s, when John Kennedy's death galvanised the space race; the feeling is that Lincoln is somehow the guardian angel of the transcontinental rail project.

Obviously, Ford was passionate about this project, filling every frame with his love of country and his belief that Americans could achieve anything through persistence, and the project certainly paid him back. The key question is whether it loves us, an audience more than 80 years in the future, and I'm not certain that the answer can be anything more impassioned than "sort of."

There's another, less pleasing way that The Iron Horse prefigured modern Oscarbait: it's incredibly mannered. Thematically, this is a John Ford film through and through, but stylistically, it's a bit too typical. Well-crafted, no doubt; and nobody but Ford would have taken a production crew to the middle of Nevada, a gambit that pays off spectacularly. But there's never a moment that takes your breath away for any reason other than sheer scope. It's possible, likely even, that Ford was so busy managing his small army that simply completing the film was a triumph. Whether that is the case or not, it's hard to argue that the film is more than very competent. It has perhaps as many shots that strongly point to its director's visual sense as Just Pals had - but it's three times as long. Working once again with director of photography George Schneiderman, as had become his habit, Ford has made something that looks a great deal like any well-funded 1920s film made by a solid creative team. Good, solid craftsmanship is nothing to sneeze at, of course. But there's simply not much that's exceptional about The Iron Horse, and it comes nowhere close to having the same aesthetic significance in the director's canon as its significance to his professional development. It's good, but a lot of other good films were coming out in the '20s. It seems that a big budget has always been enough to trick an audience into calling a solid flick a masterpiece.

At about this time, Paramount had turned a vast profit on a terribly expensive Western directed by the long-forgotten James Cruze, The Covered Wagon. It cost an extravagant $782,000 but returned an estimated $3.8 million, and Hollywood being Hollywood even in the mid-'20s (especially in the mid-'20s), it seemed like the smartest move in the world would be to sink a huge budget into an epic Western, and stand back as the money came gushing back.

Thus it was that William Fox came to produce The Iron Horse, a panoramic retelling of the quest to build the transcontinental railroad in the aftermath of the Civil War. John Ford was given more or less free reign to make the film, and that is just what he did, going weeks over schedule and thousands of dollars over budget; ultimately, the $450,000 film returned over $2 million, catapulting the Fox studio to the front echelons of Hollywood and transforming Ford instantly into one of the hottest artists in the industry.

The latter, part, at least, is surely deserved - as with most sufficiently epic-scale movies, it's hard to credit the considerable of The Iron Horse to anyone other than the director. It was Ford, after all, who insisted on taking the whole damn shoot out of Los Angeles, making the first film in American history to be shot in its entirety so far from any center of production. The filmmakers set up camp - "Camp Ford," the not-so-small community was called - in the center of the Nevada desert, where Ford set up a Kurtz-like dictatorship where his word was law and the infrequent missives from the studio were ignored as a matter of course. In this we see the first glimmer of a man whose lionisation of Monument Valley would establish him as the greatest on-location filmmaker that this country would ever know.

As a narrative, The Iron Horse looks awfully familar to the modern eye, because we see very similar films nearly every autumn. Though the Academy Awards would not exist for another four years, and Oscarbaiting for another five, it's hard to shake the feeling that The Iron Horse follows a very standard formula for awards season prestige pictures: it is about a major historic event, it seeks to reassure the audience rather than challenge them, it mixes fact with an elementally simple love story, and it even has performances that consist of very little other than looking as much as possible like a famous person. Is it irresponsible to speculate that John Ford invented the prestige epic? It is irresponsible not to.

Opening in Springfield, IL what we can safely call "around the1840s," the film centers less around a character than a process that begins when David Brandon (James Gordon) departs the settled Midwest to pursue his dream of finding a route to run rail lines all the way to California. His ideas are treated as sheer crackpottery by his neighbor Thomas Marsh (Will Walling), but his other neighbor, a lanky gent named Abe Lincoln (Charles Edward Bull) isn't so dismissive. Unfortunately, Brandon has hardly arrived in Cheyenne country when he and his son Davy (Winston Miller) are ambushed by a hunting party led by a white man with two fingers on his right hand. As the son watches from his hiding place, the father is beaten and scalped. The viewer is reminded that in 1924, there was none of this "production code" nonsense.

In 1862, Congress passes a bill that President Lincoln signs into law, authorising the construction of a railroad between Council Bluffs, IA and Sacramento, CA. The overseer of this project is none other than Thomas Marsh, who brings along his daughter Miriam (Madge Bellamy) and her much older fiancé, Marsh's assistant Jesson (Cyril Chadwick) to the site of construction near Omaha, NE. There, we find much in the way of frontier life, containing a sprawling cast of colorful figures, although the most important are Deroux (Fred Kohler), an Eevil Landowner, and Davy Brandon, all growed up and played by George O'Brien, then at the very start of his career as Fox's favorite leading man of the late silent era (he would eventually play the male lead in Sunrise, the finest thing William Fox ever touched). Scenes of Miriam torn between her childhood sweetheart and her dull fiancé alternate with rowdy Western comedy and passages that inspirationally recreate the great engineering triumph of the mid-19th Century. Scenes are also interspersed of clichéd Savage Indians, which I wouldn't ordinarily complain about - devaluing 80-year-old films because of racism offends my sense of art history - but it's surprising, given that even when they don't obviously seem like it, Ford's later films all have at least some nuance to their depiction of Native Americans.

In many ways, The Iron Horse is an archetypal John Ford film. Here we finally see the director using the power of landscape to provide a framework for his narrative - something like what Werner Herzog would later call the "voodoo of location." Here is the easy contrast between comedy and melodrama and action that would become a Ford trademark. Here is the comically (but lovingly!) overdone Irishman that would prove to be a stable of Ford's comic relief. And here, more than everything else, is the striking patriotism and love of Americana that would later wind its way through most of the director's films, however subtly.

For example, Abraham Lincoln. 15 years down the road, Ford would direct Henry Fonda for the first time in Young Mr. Lincoln, cementing his obvious love for the 16th president. The Iron Horse is something like a dry run of that theme; Lincoln hardly appears in the film for five minutes (although within those five minutes, Bull gives the most restrained and effective performance in the whole picture), but his presence haunts every moment, from the opening card (over Lincoln's bust) to the close (also over Lincoln's bust). It feels something like the country would see again in the 1960s, when John Kennedy's death galvanised the space race; the feeling is that Lincoln is somehow the guardian angel of the transcontinental rail project.

Obviously, Ford was passionate about this project, filling every frame with his love of country and his belief that Americans could achieve anything through persistence, and the project certainly paid him back. The key question is whether it loves us, an audience more than 80 years in the future, and I'm not certain that the answer can be anything more impassioned than "sort of."

There's another, less pleasing way that The Iron Horse prefigured modern Oscarbait: it's incredibly mannered. Thematically, this is a John Ford film through and through, but stylistically, it's a bit too typical. Well-crafted, no doubt; and nobody but Ford would have taken a production crew to the middle of Nevada, a gambit that pays off spectacularly. But there's never a moment that takes your breath away for any reason other than sheer scope. It's possible, likely even, that Ford was so busy managing his small army that simply completing the film was a triumph. Whether that is the case or not, it's hard to argue that the film is more than very competent. It has perhaps as many shots that strongly point to its director's visual sense as Just Pals had - but it's three times as long. Working once again with director of photography George Schneiderman, as had become his habit, Ford has made something that looks a great deal like any well-funded 1920s film made by a solid creative team. Good, solid craftsmanship is nothing to sneeze at, of course. But there's simply not much that's exceptional about The Iron Horse, and it comes nowhere close to having the same aesthetic significance in the director's canon as its significance to his professional development. It's good, but a lot of other good films were coming out in the '20s. It seems that a big budget has always been enough to trick an audience into calling a solid flick a masterpiece.

Categories: john ford, love stories, silent movies, westerns