Androids do dream of electric sheep

A second review requested by Michael R, with thanks for contributing twice to the Second Quinquennial Antagony & Ecstasy ACS Fundraiser.

The credit for the production company glides into the movie so subtly you barely even notice:

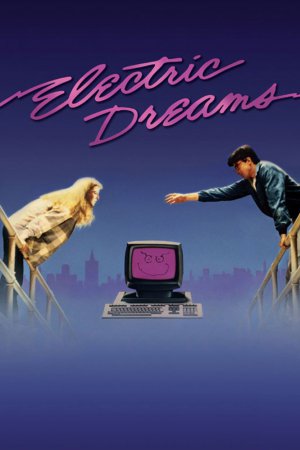

It's a feisty, lighthearted start for a movie that continues to always and primarily be those two adjectives above all others, though there's at least one other that puts in a good case for itself: pacey. But we'll get there in a moment. The first thing that an honest person writing in the second decade of the 21st Century has to concede is that, for a movie from 1984, Electric Dreams has aged in a particularly miraculous way. By which I mean that you could spend weeks hunting without finding a movie that's so enormously dated in every way. But this is the very fact that redeems the movie. Put it another way: if I were writing this review in '84, I think I would find it preposterous junk elevated by Giorgio Moroder's score and Bud Cort's vocal performance as an A.I. But I am writing in 2015, and from this point in time, Electric Dreams is such a terribly exciting time capsule from the dawn of the personal computer age that I can't stand it. We'll get there in a moment, too.

For now, just the plot. Miles Harding (Lenny Von Dohlen) is a brilliant architect but a disaster of a human, perpetually incapable of being where he needs to be on time or with all of his ideas collected. With his job hanging in the balance, he reluctantly decides to buy one of those brand new pocket computers that keeps track of dates and notes. Like a personal assistant, but one that's digital. The perky saleswoman (Wendy Miller) manages to upsell him a whole home computer set-up, along with all the widgets and doo-dads that will allow his computer to monitor all of his home appliances and basically run his whole physical life, if you can imagine something so implausible and silly.* Besides, what could an architect possibly use a computer for? Modeling his highly experimental earthquake-resistant bricks in simulated three-dimensional space, or some fantasyland bullshit like that?

Exactly that, in fact, and it's the mind-blowing realisation of what a computer can do to his workflow that finally gets Miles onboard - or make that "Moles", since he is such a complete failure at life and computers are soooooo hard that he misspells his name during set-up, and can't go back to fix it later, ho-ho. So he decides to download everything he possibly can related to his work and design, and this so taxes the 1984 internet that his computer starts to overheat. In a feverish panic, Miles pours a glass of champagne all over the keyboard, and this somehow manages to slosh all the way into the machine's hard drive where it crystallises and grants the computer sentience. As will happen.

While this has been happening, Miles has been listening to his new neighbor Madeline Robistat (Virginia Madsen) practicing cello. So, it turns out, has his computer: its first act as a self-aware being is to improvise variations on the piece she's playing and play them through its voice synthesizer. And from this point on, the story goes to relatively predictable places: the A.I., calling itself Edgar (at which point it is voiced by Cort) and Miles both fall in love with Madeline, and she falls in love with Miles on account of the beautiful electronic music he's been playing for her through the walls. And, you know, that's charming and all, if necessarily limited. It's pretty obvious that the romantic triangle is the box for the filmmakers, led by early music video director Steve Barron and writer Rusty Lemorande, to pour all their ideas into, rather than the driving force of the movie itself. Indeed, it seems entirely possible that such a generic, played-out concept as a Cyrano de Bergerac-esque romantic triangle was picked specifically so that it wouldn't get in the way of the film's fascinated portrayal of the brave new worlds of computing and synthetic music.

The none-too-exciting result of this is that Electric Dreams has absolutely no narrative urgency, particularly in its first 40 minutes (the point where Edgar gains the rudimentary power of speech). It is, not to be inelegant about it, slow as balls. And when the entire narrative justification for a film is that it's genial without being actively funny and cute without being emotionally deep, there really isn't any upside to it also being pokey about moving through its plot. And this is where that special exemption kicks in: Electric Dreams benefits to an immense degree from being an in-depth look at a very specific moment in the development of the Information Age. Watching a movie from, say, 1930, the differences between then and now seem incidental and organic - sure, the attitudes, behavior, and technology are all essentially alien, but the process by which Point A turned into Point B is clear enough that it feels like a real part of history; one we no longer inhabit, but one we evolved from. In contrast, Electric Dreams is, in so many ways, exactly like our world, such that as recently as two years ago, the film Her could speak directly to our contemporary cultural moment while telling only a slight variation on the same plot elements. Hell, Electric Dreams even opens with a sequence ironically poking fun at people so captivated by the little blinking screens in their hands that they ignore the rest of humankind, a piece of visual commentary that could be plugged into a modern movie without having to change anything but the costumes.

Despite that, there is not a single moment in Electric Dreams that feels remotely compatible with the world as it exists today - the difference between "people were just starting to figure out computers" and "people use computers several hundred times every day" turns out to be much more severe than the difference between the latter and "people have never even heard of computers, because they are top-secret codebreaking machines used to hunt Nazis". Perhaps it's because the world resembles our own so much, that the fact that everything is just slightly wrong seems intensely magnified. Perhaps it's because computers are no longer mystical, and the things that the movie tries to sell as "what the hell, who knows how these damn things work, anyway?" do not seem plausible in any way. Perhaps it's seeing people doing what we do, only they have '80s clothes and '80s hair. Whatever the hell is doing it, it means that Electric Dreams is like reading a transcript of an opium dream - you can see real life underpinning it, but the effect is otherworldly and uncanny, and it's the most amazing damn thing.

Which is exactly why I feel like I'd have ignored if not hated this movie when it was new: all of the things that seem dazzlingly weird about it now were just the world outside in 1984. Or at least, the world as practiced by tech geeks, far away on the outskirts of polite society. All that leaves is the story, which really isn't all that interesting: Von Dohlen and Madsen make for pleasant but largely bland and shallow human leads, leaving no real focal point of personality until Cort finally comes to the rescue with his tartly mechanical line readings, as if HAL 9000 grew up listening to the Clash.

But even taken on its own terms, this isn't really about its story. Barron's music director instincts drive the film more than his narrative instincts. That means that most of the images where are interesting tend to exist in a vacuum: the example that leaps to mind is the profile shot of Miles in the computer story, his face appearing on a CCTV monitor that's blocking his upper body. Pretty much any shot of Edgar's abstract color-and-line interface is coming from the same place, more interesting graphically and perhaps because of what it says about computer culture, than because of what it says about this computer in this scenario.

Even more than that, though, Barron's intentions for the movie lead him to gift the entire thing to Moroder and company ("and company" meaning New Wave groups Culture Club and Heaven 17); this isn't a long-form music video to quite the same extreme that, say, TRON: Legacy is, but that's still probably the level on which it's most successful. And why not? Moroder was the guru of making music through electronics; it's right on a very nearly moral level that he'd be called in to provide the audio background for a story about what computers feel and how they express those feelings through song. It sounds perfect: nothing about the film makes Edgar so real as the music that essentially places us inside his head at the expense of Miles and Madeline, but since Edgar is more interesting than they are, it's no real loss. The film sounds every bit as quintessentially of the early-middle '80s as it looks and acts like it, and this completes its flawlessness as a time capsule; and the music, at least can be enjoyed unironically. Or as unironically as we enjoy any of Moroder's work, anyway. The end result of all this isn't great cinema, or even particularly good cinema; but it's sure as hell attention-grabbing.

The credit for the production company glides into the movie so subtly you barely even notice:

A VIRGIN PICTURES PRODUCTION

hello

HELLO

is this a story?

YES

what type?

FAIRYTALE FOR COMPUTERS

name?

ELECTRIC DREAMS

It's a feisty, lighthearted start for a movie that continues to always and primarily be those two adjectives above all others, though there's at least one other that puts in a good case for itself: pacey. But we'll get there in a moment. The first thing that an honest person writing in the second decade of the 21st Century has to concede is that, for a movie from 1984, Electric Dreams has aged in a particularly miraculous way. By which I mean that you could spend weeks hunting without finding a movie that's so enormously dated in every way. But this is the very fact that redeems the movie. Put it another way: if I were writing this review in '84, I think I would find it preposterous junk elevated by Giorgio Moroder's score and Bud Cort's vocal performance as an A.I. But I am writing in 2015, and from this point in time, Electric Dreams is such a terribly exciting time capsule from the dawn of the personal computer age that I can't stand it. We'll get there in a moment, too.

For now, just the plot. Miles Harding (Lenny Von Dohlen) is a brilliant architect but a disaster of a human, perpetually incapable of being where he needs to be on time or with all of his ideas collected. With his job hanging in the balance, he reluctantly decides to buy one of those brand new pocket computers that keeps track of dates and notes. Like a personal assistant, but one that's digital. The perky saleswoman (Wendy Miller) manages to upsell him a whole home computer set-up, along with all the widgets and doo-dads that will allow his computer to monitor all of his home appliances and basically run his whole physical life, if you can imagine something so implausible and silly.* Besides, what could an architect possibly use a computer for? Modeling his highly experimental earthquake-resistant bricks in simulated three-dimensional space, or some fantasyland bullshit like that?

Exactly that, in fact, and it's the mind-blowing realisation of what a computer can do to his workflow that finally gets Miles onboard - or make that "Moles", since he is such a complete failure at life and computers are soooooo hard that he misspells his name during set-up, and can't go back to fix it later, ho-ho. So he decides to download everything he possibly can related to his work and design, and this so taxes the 1984 internet that his computer starts to overheat. In a feverish panic, Miles pours a glass of champagne all over the keyboard, and this somehow manages to slosh all the way into the machine's hard drive where it crystallises and grants the computer sentience. As will happen.

While this has been happening, Miles has been listening to his new neighbor Madeline Robistat (Virginia Madsen) practicing cello. So, it turns out, has his computer: its first act as a self-aware being is to improvise variations on the piece she's playing and play them through its voice synthesizer. And from this point on, the story goes to relatively predictable places: the A.I., calling itself Edgar (at which point it is voiced by Cort) and Miles both fall in love with Madeline, and she falls in love with Miles on account of the beautiful electronic music he's been playing for her through the walls. And, you know, that's charming and all, if necessarily limited. It's pretty obvious that the romantic triangle is the box for the filmmakers, led by early music video director Steve Barron and writer Rusty Lemorande, to pour all their ideas into, rather than the driving force of the movie itself. Indeed, it seems entirely possible that such a generic, played-out concept as a Cyrano de Bergerac-esque romantic triangle was picked specifically so that it wouldn't get in the way of the film's fascinated portrayal of the brave new worlds of computing and synthetic music.

The none-too-exciting result of this is that Electric Dreams has absolutely no narrative urgency, particularly in its first 40 minutes (the point where Edgar gains the rudimentary power of speech). It is, not to be inelegant about it, slow as balls. And when the entire narrative justification for a film is that it's genial without being actively funny and cute without being emotionally deep, there really isn't any upside to it also being pokey about moving through its plot. And this is where that special exemption kicks in: Electric Dreams benefits to an immense degree from being an in-depth look at a very specific moment in the development of the Information Age. Watching a movie from, say, 1930, the differences between then and now seem incidental and organic - sure, the attitudes, behavior, and technology are all essentially alien, but the process by which Point A turned into Point B is clear enough that it feels like a real part of history; one we no longer inhabit, but one we evolved from. In contrast, Electric Dreams is, in so many ways, exactly like our world, such that as recently as two years ago, the film Her could speak directly to our contemporary cultural moment while telling only a slight variation on the same plot elements. Hell, Electric Dreams even opens with a sequence ironically poking fun at people so captivated by the little blinking screens in their hands that they ignore the rest of humankind, a piece of visual commentary that could be plugged into a modern movie without having to change anything but the costumes.

Despite that, there is not a single moment in Electric Dreams that feels remotely compatible with the world as it exists today - the difference between "people were just starting to figure out computers" and "people use computers several hundred times every day" turns out to be much more severe than the difference between the latter and "people have never even heard of computers, because they are top-secret codebreaking machines used to hunt Nazis". Perhaps it's because the world resembles our own so much, that the fact that everything is just slightly wrong seems intensely magnified. Perhaps it's because computers are no longer mystical, and the things that the movie tries to sell as "what the hell, who knows how these damn things work, anyway?" do not seem plausible in any way. Perhaps it's seeing people doing what we do, only they have '80s clothes and '80s hair. Whatever the hell is doing it, it means that Electric Dreams is like reading a transcript of an opium dream - you can see real life underpinning it, but the effect is otherworldly and uncanny, and it's the most amazing damn thing.

Which is exactly why I feel like I'd have ignored if not hated this movie when it was new: all of the things that seem dazzlingly weird about it now were just the world outside in 1984. Or at least, the world as practiced by tech geeks, far away on the outskirts of polite society. All that leaves is the story, which really isn't all that interesting: Von Dohlen and Madsen make for pleasant but largely bland and shallow human leads, leaving no real focal point of personality until Cort finally comes to the rescue with his tartly mechanical line readings, as if HAL 9000 grew up listening to the Clash.

But even taken on its own terms, this isn't really about its story. Barron's music director instincts drive the film more than his narrative instincts. That means that most of the images where are interesting tend to exist in a vacuum: the example that leaps to mind is the profile shot of Miles in the computer story, his face appearing on a CCTV monitor that's blocking his upper body. Pretty much any shot of Edgar's abstract color-and-line interface is coming from the same place, more interesting graphically and perhaps because of what it says about computer culture, than because of what it says about this computer in this scenario.

Even more than that, though, Barron's intentions for the movie lead him to gift the entire thing to Moroder and company ("and company" meaning New Wave groups Culture Club and Heaven 17); this isn't a long-form music video to quite the same extreme that, say, TRON: Legacy is, but that's still probably the level on which it's most successful. And why not? Moroder was the guru of making music through electronics; it's right on a very nearly moral level that he'd be called in to provide the audio background for a story about what computers feel and how they express those feelings through song. It sounds perfect: nothing about the film makes Edgar so real as the music that essentially places us inside his head at the expense of Miles and Madeline, but since Edgar is more interesting than they are, it's no real loss. The film sounds every bit as quintessentially of the early-middle '80s as it looks and acts like it, and this completes its flawlessness as a time capsule; and the music, at least can be enjoyed unironically. Or as unironically as we enjoy any of Moroder's work, anyway. The end result of all this isn't great cinema, or even particularly good cinema; but it's sure as hell attention-grabbing.

Categories: comedies, love stories, romcoms, science fiction