Summer of Blood: New Hollywood Horror - Little devil

There is an exact line of descent, and it curls around the spine of the early '70s Zeitgeist like smoke coiling over a burning log. First there was Rosemary's Baby, the book, and it got people talking, and then it begat Rosemary's Baby the movie, and it was an explosive moment. The story of a lapsed Catholic confronted with the literal reality of the spirit world and pure Satanic evil captured the imagination and attention of a whole culture, perhaps because it came at exactly a perfect time: 1968 was probably the most tumultuous and destructive single year in post-WWII Euro-American history, and it was an appealing time to have something purely evil to grab hold of and blame. The actual, for-real Devil is a good fixation for the imagination staring at a world that was apparently becoming less coherent and explicable by the week (and that holds true for the revolutionary as well as the reactionary elements in society; the '68-'74 corridor in America at least is notable for how both the Left and the Right were convinced that they were losing). And so began a passion for Satanism in fiction that spiked with The Exorcist: the book in 1971, the movie in 1973 - and if Rosemary's Baby was a big deal in the movie theaters, The Exorcist was positively seismic. It was, for a couple of years, the highest-grossing film in history, cementing into pop culture (and real life!) an obsession with the obscure and mostly discarded Catholic rite of exorcism that hasn't flagged in more than four decades since. It was the perfect movie for any pessimistic attitude you wanted to put out there in '73: the Powers That Be are just as broken and helpless as the little people, and the people we look to for guidance are just as lost as we are. And there is real, true evil in the world, and it's winning.

Setting aside its amazing cultural stickiness, movies don't make that much money without inspiring imitators, and The Exorcist boasts as many knock-offs as any '70s hit film that side of Jaws. And like Jaws, those knock-offs came in two flavors: the ones that actively pillaged its plot and characters such as to effectively rebuild it in different clothes (or in the case of Abby, which was sued out of theaters, the same clothes worn by African-Americans), or the artier, more thoughtful sort of knock-off, which took advantage of the atmosphere produced by this giant blockbuster to make a film that echoes its genre without specifically copying it in any way.

There is surely no clone of The Exorcist to play this second kind of game more elegantly or to great cultural omnipresence than 20th Century Fox's The Omen of 1976, written by David Seltzer and directed by Richard Donner. It is, verily, the only other religious horror film of that era to still live in the general imagination purely on its own strengths, rather than those it borrows; the third leg of what the great Satanism Trilogy that came about in the wake of the counterculture. It completes a circuit around mainstream Christianity begun by its precursors: Rosemary's Baby is essentially agnostic, with its title character flagging her lack of faith and attempting to use reason and science to save herself until it's much too late (though the film is Catholic around the edges, particularly in its finale a grotesque parody of the Madonna and Child); The Exorcist is explicitly and purposefully Catholic. The Omen, meanwhile, is more generically Protestant in its eschatology, its mistrust of the Roman Church (three members of the Catholic clergy are shown at any length; two of them are eventually revealed to be the literal servants of evil), and its overall American blue blood WASPiness; after all, that's that the "P" in "WASP" stands for in the first place. And I would at this point mention that during the '70s, the United States experienced a revival of hardcore fundamentalist Protestantism more or less unprecedented in contemporary industrial society, with the blood-and-thunder angst about the End Times that comes with it; The Omen might not have been a deliberate attempt to appeal to that nascent market, but it couldn't have had better timing if it was all just an innocent accident of fate.

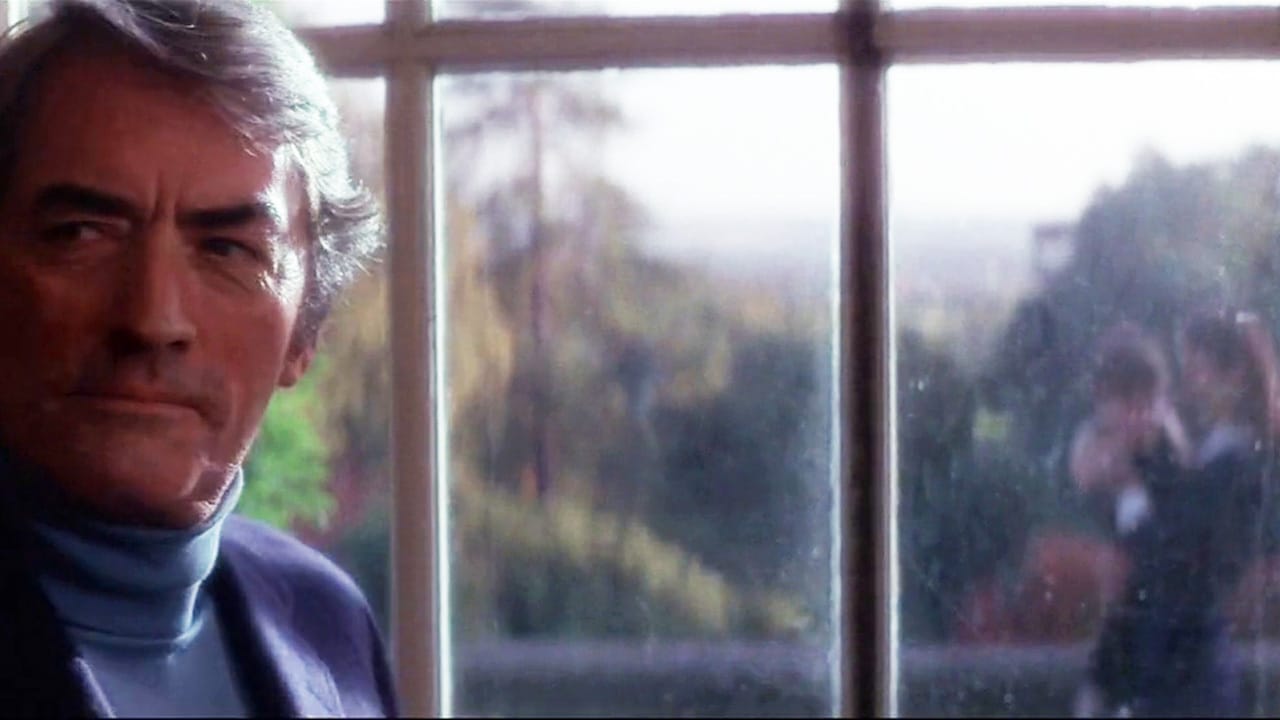

None of this pop-sociology needs to bother us as we turn towards the film itself, which opens with a virtually flawless piece of exposition by way of disorientation. At 6:00 AM on 6 June, over footage of Gregory Peck driving through the Roman night - we will eventually get to know his character as Robert Thorn - we hear the calm voice of a man we know must be a priest, he speaks with such a perfect mix of authority and comforting mournfulness: "The child is dead. He breathed for a moment. Then he breathed no more. The child is dead." We haven't even caught up yet, but we know exactly what we need to, and the discontinuous way that sound and image are mixed, alongside the inherent gloominess of the images themselves, sticks us right into the shocked, funereal mood the movie needs to establish immediately, if it's ever going to sell the next bit.

Because the next bit is a baby swap. That sad-sounding priest, Father Spiletto (Martin Benson), has a suggestion for Mr. Thorn: in a shocking turn of events, another baby was born at the same moment as the deceased Thorn infant, and its mother died. So that's one set of parents without a baby, and one baby without parents. It takes hardly any convincing for Spiletto and the eager-looking nun (Freda Dowie) caring for the newborn to talk the distraught Thorn into adopting the orphan under the table, and telling nobody, not even his wife Katherine (Lee Remick), what happened. And having made that deal with the Devil - spoilers, sorry! - the Thorns live out the next five years happily, especially after Robert's good friend, the President of the United States, appoints him to be the ambassador to the United Kingdom. From here, life proceeds as it will for the extraordinarily well-to-do, right up until little Damien Thorn's (Harvey Stephens) fifth birthday party. For the first time, presumably, in the family's happy little life, things start to go curious and terrifying: first, a Rottweiler arrives from nowhere to lurk around the edges of the Thorn's palatial home, growling horribly at everyone who encounters it. Then, Damien's nanny (Holly Palance) makes a big show of interrupting the party to shot "Look at me, Damien! It's all for you!". It being, in this case, putting a noose around her neck and jumping from the balcony to hang herself in front of all those families.

Creepiness starts to pile up immediately: the almost literally raving Father Brennan (Patrick Troughton) starts badgering Robert about accepting the blood of Christ, like right this very second before it's too late, because something is horribly wrong with Damien. Robert would prefer to ignore this turbulent priest, but Father Brennan knows things he simply can't, including the fact that Katherine is pregnant. Shortly thereafter, a certain Mrs. Baylock (Billie Whitelaw) arrives to be Damien's new nanny, with neither of the Thorns quite understanding how she managed to get there. But that omnipresent dog sure does like her. And most upsettingly, a routine trip to the zoo turns into a hellish nightmare when the animals start to get acutely terrified by Damien's presence, particularly the baboons in the drive-through baboon enclosure (zoos in England are apparently not like zoos in the States), who start aggressively attacking the car and sending Katherine into a nervous fit.

Things come to a head when a freak storm causes an almost unbearably contrived accident that kills Father Brennan. It just so happens that the crabby photojournalist Keith Jennings (David Warner) took a photo of the father some while back that shows a black streak exactly corresponding to the injury that killed him; he also had a similar photo of the Thorn nanny from when he resentfully was assigned to photograph the party for some society rag or another. He and Robert team up to figure what the hell might be going on, and it takes them to Italy, where they make all kinds of deeply unpleasant discoveries, thence to Israel, where the archaeologist Bugenhagen (Leo McKern) does away with all the mystery to make it emphatically clear: here's how to prove that Damien is the Antichrist of legend, and here's how to kill him, and tough shit if that doesn't sit well with you, daddy. But the forces of Satan have some tricks up their sleeve to make Robert and Keith's attempt to slaughter a five-year-old boy harder than it ought to be.

I am happy to report that The Omen is much better than my long out-of-date memories of it; I had it down as a movie good for nothing but its corral of character actors and Jerry Goldsmith's angry, glowering, chant-driven score (the only one for which America's greatest home-grown composer won an Oscar). There's much more to like about it than that, even you have to pick it out of the dross a bit. It's very much the case, for one thing, that the movie significantly misunderstands the difference between "that is scary" and "that is honestly a bit hokey" - it is very much over-invested in the inherent creepiness of barking dogs, for one thing, and I get that if somebody has a thing about dogs (or even just traditional attack dogs), all those close-ups of dogs are probably Hell itself. But they're not even, like hellhounds. They're just Rottweilers. Not even Goldsmith's special pleading can change my mind on that fact. The only time the dogs work as a source of real dread is during Robert and Keith's visit to an ancient cemetery in Italy, where the go-for-broke production design, with bucketloads of fog everywhere, and jagged POV camerawork with heavy breathing announcing the dogs before we see them are sufficient to sell a really fine level of Gothic horror.

The other thing the movie loves for no good reason? Slow-motion. Everything is more terrifying if you slow it down, apparently. Lee Remick falls from a great height in slow motion twice. It's much goofier the second time for a lot of reasons, costume and landing pad among them.

But let me accentuate the positive for a bit. The iconic parts are all great: the nanny's beatific smile as she kills herself is skin-crawling stuff; Troughton's delivery of the line "His mother was a ja-!" is exactly the right kind of panicked frenzy that we can't make out whether he's a terrified wise man or a total loony, but it's freaky either way; and all the little shots of Stephens sitting there with the blank curiosity of a small child gain bone-chilling effectiveness they more they pile up (my favorite, though, comes early: it's his deeply thoughtful expression upon seeing Mrs. Baylock for the first time). The film's signature gore sequence, an unusually inventive decapitation shown from multiple angles in (sigh) slow-motion, is astonishing, upsetting for its suddenness, for the way it happens to somebody we've quickly gained a sense of as smart and capable, and for its explicitness, frankly. I am largely unmoved by Peck's performance - he seems much too old for the part, and rather more fatigued than worried - but the rest of the cast ranges from better-than-necessary to thoroughly great, and it's really only McKern in a pointlessly small cameo who falls at the bottom edge of that range.

Much of the film is terrific, unnerving stuff; but much of it is kind of loopy and much too silly to take even a little seriously. The big problem with the film is Donner; mostly trained in television, with just three theatrical features to his name in a sixteen-year career, this was the director's first horror movie. Tellingly, despite this film turning into a giant hit that made his career, it was also his last horror movie, not withstanding the brief asides in that direction peppering the holiday comedy Scrooged. The truly great horror directors blend the absurd with the terrifying so flawlessly that you cannot tell where the gap between them lies; the very good ones have the sense to not point the camera at things that are going to look ridiculous. The Omen is merely competent: for every sucker punch, like the reveal of what's in the cemetery and what it says about the story Robert Thorn was sold, there's the ludicrous, overcut baboon sequence; for every energetically grisly decapitation, there's the sheepish, helpless way that Father Brennan is killed by a pole on a string that looks like a Monty Python gag. It's not the problem, exactly, that The Omen fails to find a tone - there's really not a comic moment to be found, except for the most deeply sardonic, and after Damien pushes Katherine over a second-story railing midway through, the dread monunts at a steady pace. The problem is that the tone isn't consistently executed well, and there are too many points throughout the film's running time that are just plain stupid. Coupled with how much more of a shabby shocker this is than its more august elder siblings - no complex character drama here, just a mysterious cabal of Satanists - and it's hard to say that The Omen fully earns its status as a horror classic even if it does have its fair share of individually powerful moments.

Body Count: 6, more if we count the Thorns' baby and Damien's mother who both technically do die during the course of the narrative. More still if we count the millions upon millions of souls to be devoured during Satan's reign on Earth.

Setting aside its amazing cultural stickiness, movies don't make that much money without inspiring imitators, and The Exorcist boasts as many knock-offs as any '70s hit film that side of Jaws. And like Jaws, those knock-offs came in two flavors: the ones that actively pillaged its plot and characters such as to effectively rebuild it in different clothes (or in the case of Abby, which was sued out of theaters, the same clothes worn by African-Americans), or the artier, more thoughtful sort of knock-off, which took advantage of the atmosphere produced by this giant blockbuster to make a film that echoes its genre without specifically copying it in any way.

There is surely no clone of The Exorcist to play this second kind of game more elegantly or to great cultural omnipresence than 20th Century Fox's The Omen of 1976, written by David Seltzer and directed by Richard Donner. It is, verily, the only other religious horror film of that era to still live in the general imagination purely on its own strengths, rather than those it borrows; the third leg of what the great Satanism Trilogy that came about in the wake of the counterculture. It completes a circuit around mainstream Christianity begun by its precursors: Rosemary's Baby is essentially agnostic, with its title character flagging her lack of faith and attempting to use reason and science to save herself until it's much too late (though the film is Catholic around the edges, particularly in its finale a grotesque parody of the Madonna and Child); The Exorcist is explicitly and purposefully Catholic. The Omen, meanwhile, is more generically Protestant in its eschatology, its mistrust of the Roman Church (three members of the Catholic clergy are shown at any length; two of them are eventually revealed to be the literal servants of evil), and its overall American blue blood WASPiness; after all, that's that the "P" in "WASP" stands for in the first place. And I would at this point mention that during the '70s, the United States experienced a revival of hardcore fundamentalist Protestantism more or less unprecedented in contemporary industrial society, with the blood-and-thunder angst about the End Times that comes with it; The Omen might not have been a deliberate attempt to appeal to that nascent market, but it couldn't have had better timing if it was all just an innocent accident of fate.

None of this pop-sociology needs to bother us as we turn towards the film itself, which opens with a virtually flawless piece of exposition by way of disorientation. At 6:00 AM on 6 June, over footage of Gregory Peck driving through the Roman night - we will eventually get to know his character as Robert Thorn - we hear the calm voice of a man we know must be a priest, he speaks with such a perfect mix of authority and comforting mournfulness: "The child is dead. He breathed for a moment. Then he breathed no more. The child is dead." We haven't even caught up yet, but we know exactly what we need to, and the discontinuous way that sound and image are mixed, alongside the inherent gloominess of the images themselves, sticks us right into the shocked, funereal mood the movie needs to establish immediately, if it's ever going to sell the next bit.

Because the next bit is a baby swap. That sad-sounding priest, Father Spiletto (Martin Benson), has a suggestion for Mr. Thorn: in a shocking turn of events, another baby was born at the same moment as the deceased Thorn infant, and its mother died. So that's one set of parents without a baby, and one baby without parents. It takes hardly any convincing for Spiletto and the eager-looking nun (Freda Dowie) caring for the newborn to talk the distraught Thorn into adopting the orphan under the table, and telling nobody, not even his wife Katherine (Lee Remick), what happened. And having made that deal with the Devil - spoilers, sorry! - the Thorns live out the next five years happily, especially after Robert's good friend, the President of the United States, appoints him to be the ambassador to the United Kingdom. From here, life proceeds as it will for the extraordinarily well-to-do, right up until little Damien Thorn's (Harvey Stephens) fifth birthday party. For the first time, presumably, in the family's happy little life, things start to go curious and terrifying: first, a Rottweiler arrives from nowhere to lurk around the edges of the Thorn's palatial home, growling horribly at everyone who encounters it. Then, Damien's nanny (Holly Palance) makes a big show of interrupting the party to shot "Look at me, Damien! It's all for you!". It being, in this case, putting a noose around her neck and jumping from the balcony to hang herself in front of all those families.

Creepiness starts to pile up immediately: the almost literally raving Father Brennan (Patrick Troughton) starts badgering Robert about accepting the blood of Christ, like right this very second before it's too late, because something is horribly wrong with Damien. Robert would prefer to ignore this turbulent priest, but Father Brennan knows things he simply can't, including the fact that Katherine is pregnant. Shortly thereafter, a certain Mrs. Baylock (Billie Whitelaw) arrives to be Damien's new nanny, with neither of the Thorns quite understanding how she managed to get there. But that omnipresent dog sure does like her. And most upsettingly, a routine trip to the zoo turns into a hellish nightmare when the animals start to get acutely terrified by Damien's presence, particularly the baboons in the drive-through baboon enclosure (zoos in England are apparently not like zoos in the States), who start aggressively attacking the car and sending Katherine into a nervous fit.

Things come to a head when a freak storm causes an almost unbearably contrived accident that kills Father Brennan. It just so happens that the crabby photojournalist Keith Jennings (David Warner) took a photo of the father some while back that shows a black streak exactly corresponding to the injury that killed him; he also had a similar photo of the Thorn nanny from when he resentfully was assigned to photograph the party for some society rag or another. He and Robert team up to figure what the hell might be going on, and it takes them to Italy, where they make all kinds of deeply unpleasant discoveries, thence to Israel, where the archaeologist Bugenhagen (Leo McKern) does away with all the mystery to make it emphatically clear: here's how to prove that Damien is the Antichrist of legend, and here's how to kill him, and tough shit if that doesn't sit well with you, daddy. But the forces of Satan have some tricks up their sleeve to make Robert and Keith's attempt to slaughter a five-year-old boy harder than it ought to be.

I am happy to report that The Omen is much better than my long out-of-date memories of it; I had it down as a movie good for nothing but its corral of character actors and Jerry Goldsmith's angry, glowering, chant-driven score (the only one for which America's greatest home-grown composer won an Oscar). There's much more to like about it than that, even you have to pick it out of the dross a bit. It's very much the case, for one thing, that the movie significantly misunderstands the difference between "that is scary" and "that is honestly a bit hokey" - it is very much over-invested in the inherent creepiness of barking dogs, for one thing, and I get that if somebody has a thing about dogs (or even just traditional attack dogs), all those close-ups of dogs are probably Hell itself. But they're not even, like hellhounds. They're just Rottweilers. Not even Goldsmith's special pleading can change my mind on that fact. The only time the dogs work as a source of real dread is during Robert and Keith's visit to an ancient cemetery in Italy, where the go-for-broke production design, with bucketloads of fog everywhere, and jagged POV camerawork with heavy breathing announcing the dogs before we see them are sufficient to sell a really fine level of Gothic horror.

The other thing the movie loves for no good reason? Slow-motion. Everything is more terrifying if you slow it down, apparently. Lee Remick falls from a great height in slow motion twice. It's much goofier the second time for a lot of reasons, costume and landing pad among them.

But let me accentuate the positive for a bit. The iconic parts are all great: the nanny's beatific smile as she kills herself is skin-crawling stuff; Troughton's delivery of the line "His mother was a ja-!" is exactly the right kind of panicked frenzy that we can't make out whether he's a terrified wise man or a total loony, but it's freaky either way; and all the little shots of Stephens sitting there with the blank curiosity of a small child gain bone-chilling effectiveness they more they pile up (my favorite, though, comes early: it's his deeply thoughtful expression upon seeing Mrs. Baylock for the first time). The film's signature gore sequence, an unusually inventive decapitation shown from multiple angles in (sigh) slow-motion, is astonishing, upsetting for its suddenness, for the way it happens to somebody we've quickly gained a sense of as smart and capable, and for its explicitness, frankly. I am largely unmoved by Peck's performance - he seems much too old for the part, and rather more fatigued than worried - but the rest of the cast ranges from better-than-necessary to thoroughly great, and it's really only McKern in a pointlessly small cameo who falls at the bottom edge of that range.

Much of the film is terrific, unnerving stuff; but much of it is kind of loopy and much too silly to take even a little seriously. The big problem with the film is Donner; mostly trained in television, with just three theatrical features to his name in a sixteen-year career, this was the director's first horror movie. Tellingly, despite this film turning into a giant hit that made his career, it was also his last horror movie, not withstanding the brief asides in that direction peppering the holiday comedy Scrooged. The truly great horror directors blend the absurd with the terrifying so flawlessly that you cannot tell where the gap between them lies; the very good ones have the sense to not point the camera at things that are going to look ridiculous. The Omen is merely competent: for every sucker punch, like the reveal of what's in the cemetery and what it says about the story Robert Thorn was sold, there's the ludicrous, overcut baboon sequence; for every energetically grisly decapitation, there's the sheepish, helpless way that Father Brennan is killed by a pole on a string that looks like a Monty Python gag. It's not the problem, exactly, that The Omen fails to find a tone - there's really not a comic moment to be found, except for the most deeply sardonic, and after Damien pushes Katherine over a second-story railing midway through, the dread monunts at a steady pace. The problem is that the tone isn't consistently executed well, and there are too many points throughout the film's running time that are just plain stupid. Coupled with how much more of a shabby shocker this is than its more august elder siblings - no complex character drama here, just a mysterious cabal of Satanists - and it's hard to say that The Omen fully earns its status as a horror classic even if it does have its fair share of individually powerful moments.

Body Count: 6, more if we count the Thorns' baby and Damien's mother who both technically do die during the course of the narrative. More still if we count the millions upon millions of souls to be devoured during Satan's reign on Earth.

Categories: horror, satanistas, summer of blood