They Shoot Pictures, Don't They? 2008 Edition - #614

The traditional means for going beyond straight seriousness - irony, satire - seem feeble today, inadequate to the culturally oversaturated medium in which contemporary sensibility is schooled. Camp introduces a new standard: artifice as an ideal, theatricality.

-Susan Sontag

It's such a fine line between stupid and clever.

-David St. Hubbins

This is my happening and it freaks me out!

-Future Pulitzer Prize-winning film critic Roger Ebert

It's hard to know where to begin discussing Beyond the Valley of the Dolls. I would like very much to open by considering its place in the career of Russ Meyer, one of the key figures in the history of exploitation cinema, but I'm very ashamed to admit that this is the first and only film I've seen by Russ Meyer.* Certainly, I know what everyone knows about the director, that he loved to make live-action cartoons about large-breasted women committing acts of sex and violence; I have heard it said that he considered BtVotD to be the greatest work of his career. That's all I know. With that said, I'm not certain that the film really needs any context. It was made in a unique time and place by a unique sensibility, without a doubt, but it is also a sort of perfect object; it justifies itself by its existence and by the relationship it builds with the viewer.

BtVotD allegedly began life as a sequel to Mark Robson's anemic filmed version of Jacqueline Susan's classically overwrought potboiler Valley of the Dolls, but so quickly turned into an over-the-top parody of that film that 20th Century Fox demanded that Meyer open with a solemn title card declaring that the two films had nothing in common besides a few matters of theme.

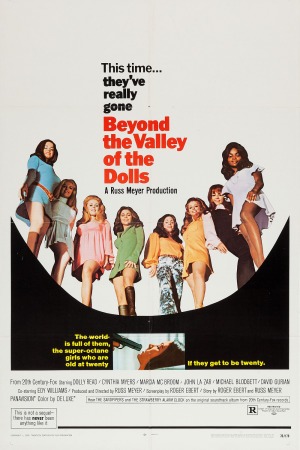

Meyer's film follows the career of a trio of grrl rockers, known as The Kelly Affair: Kelly MacNamara (Dolly Read, Playboy Playmate of the Month in May '66), Casey Anderson (Cynthia Myers, Playboy Playmate of the Month in December '68) and Pet Danforth (Marcia McBroom, never a Playboy Playmate of the Month), and their manager, Kelly's boyfriend Harris (David Gurian, who once worked as a photographer for Playboy). Seeking more excitement, fame and fortune than their drowsy Texas town could provide, the quartet travels to Los Angeles to meet Kelly's wealthy aunt Susan Lake (Phyllis Davis) and her scheming business partner Porter Hall (Duncan McLeod). They very night they arrive, Susan has been invited to a party, and she brings them along; what they find at the ostentatious home of the ambiguously bisexually gay hermaphrodite and Phil Spector analogue Ronnie "Z-Man" Barzell (John LaZar) will forever change their lives. The band is recast as The Carrie Nations, a hard rock folk group (or something), and the girls' success turns Kelly into a money-hungry whore, Casey into a pill-popping drunk and Pet into a comparatively uncomplicated slut.

The one thing that everybody knows about Beyond the Valley of the Dolls is that it was written by future Pulitzer Prize-winning film critic Roger Ebert, three years into his career at the Chicago Sun-Times. This is typically offered up as a skeleton in the closet, proof that Pulitzer Prize-winning film critic Roger Ebert isn't so all-knowing as he might seem to be. Except that Pulitzer Prize-winning film critic Roger Ebert has never made any real effort to hide the fact that he wrote this film, that he is in fact proud of this film, and he and co-scenarist Russ Meyer never intended for the film to be taken as anything other than a tongue-in-cheek farce, a satire of the excesses of the 1960s and of films about the excesses of the 1960s, and a good old-fashioned sex romp like Meyer cut his teeth on, and more-or-less invented with 1959's The Immortal Mr. Teas, typically called the first nudie-cutie. You may want to call Pulitzer Prize-winning film critic Roger Ebert a liar, but there's no need to take his word for it: while plenty of films almost indistinguishable from this one were played completely sincerely, particularly those made under the influence of the many free-flowing drugs in the late 1960s and early 1970s, it's that "almost" that really makes the difference. There are just enough hints that this is all meant to be very silly that the attentive viewer will be in on the joke, long before the film tips its hand with the apparently psychotic finale (conceived by Meyer and future Pulitzer Prize-winning film critic Roger Ebert on the day of shooting). It is in fact a very smart film, not a guilty pleasure even for those who like to think that pleasures need to be guilty, but simply a straight-up fun sex comedy.

But I'm not interested in mounting a defense of the movie. I quoted Sontag at the beginning for a reason (and if you haven't read the linked essay, "Notes on Camp," please do; it is an essential work of cultural criticism). BtVotD, like a John Waters film, is beyond judgment. If you love it the way it should be loved, you're in on the joke; if you hate it then you're part of the joke. More than its value as camp parody, the film is fascinating and perhaps surprising for how smartly it's all put together. As I said: I am no Russ Meyer scholar, but if this film is any indication, he was actually a pretty good filmmaker.

The film is honestly a well-constructed thriller from the word "go": the opening scene, deliberately framed and edited for maximum impact without every letting us see exactly which characters are involved, is a note-perfect bit of suspense filmmaking. A figure in a red velvet cape stalks through a ritzy house, coming upon a naked woman in a bed and shooting her with a handgun. We have no idea what's going on precisely, and the fact that this is all going on underneath the opening credits makes it a bit more confusing, but these are good things: we are kept in suspense. It's not hard, as the film's cavalcade of nudity and ludicrous dialogue unspool, to forget that this happened, but when that red cape reappears at the end, it's a moment as shocking as anything in Hitchcock.

That's well and good, yet it's not entirely what I meant by "well-constructed." The film's momentum is kept at a high pitch through an editing conceit that ought to be annoying, and at first it is. Every scene that ends with a line of dialogue (and that includes most of them) cuts a few frames before the sound ends, so that a new scene always begins with the previous scene literally ringing in our ears. Most of the shots within scenes are similar. This is a classic trick called overlap editing, and it's hardly a clever technique, but I've not seen too many movies where it's used almost constantly as it is here. It keeps the picture editing from punctuating the scenes: that is, scenes are not made up of individual moments that start and stop. The scenes rather flow almost hastily from shot to shot, so that the film never seems to take a pause, and since the same technique is used to connect scenes (and that is clever, or at least not nearly so common), the movie as a whole has the same feeling of ceaseless flow. Not that a movie about naked female potheads could ever be "dull", but the editing here is conspicuously good at keeping the pace of the film very high, and that lets the film get away with a nearly two-hour running time that would otherwise be anathema to an exploitation picture.

As far as its visuals go, BtVotD was shot by Fred J. Koenekamp, an Oscar nominee that same year for Patton, and while nobody would claim that the cinematography in Meyer's epic was quite that good, it's unmistakably the work of someone who knew what the hell he was doing, if only for the amazing colors that pepper the film. Besides that, the imagery, more than the screenplay, is part of how we get the joke. The example that leaps to mind - it's a combination of photography, directing and editing, and can't be solely credited to any - occurs twice, during two of the band's numbers. The girls are in the center, with Z-Man and Harris superimposed on either side - ordinary stuff, showing how the impresario is the devil and the now-discarded boyfriend is the face of goodness and light. The gag comes when the superimposed faces start to shoot each other dirty looks. They can't see each other - this has been established - and so the moment is clearly a meta-cinematic joke, not just within the film's context, but also against all the films that use similar visuals as an obvious cliché.

I could probably go on, but you get the picture. This is smart and exploitative; gaudy and lurid but winking as it goes. It is the very definition of self-conscious camp, certainly not Art but much too intelligent for Trash. It prefigures the grind house; it prefigures Grindhouse; it is good dirty fun, with equal emphasis on all three.