They Shoot Pictures, Don't They? 2008 Edition - #675

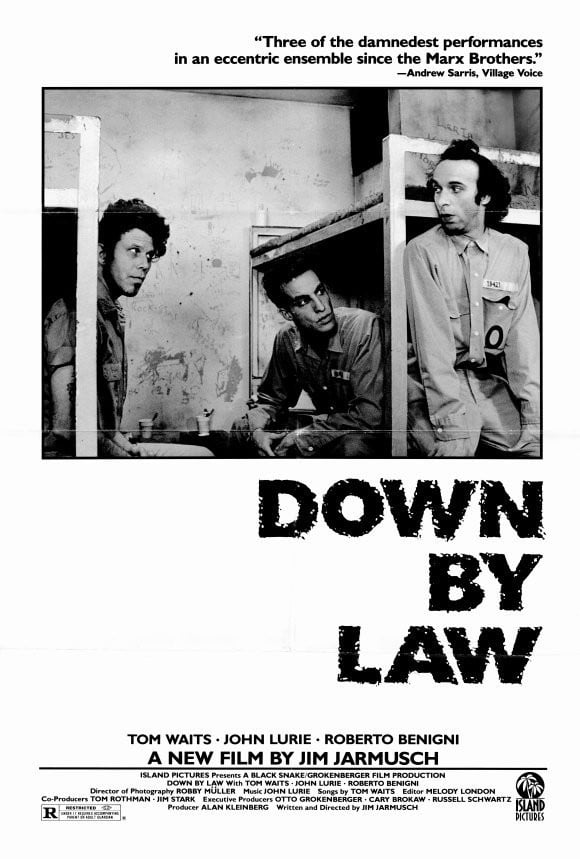

I think it best to begin by explaining what Down by Law isn't: a prison escape movie, a study of the places and cultures of Louisiana, a buddy movie, or a cryptic celebration of beatnik jazz. It's important to clarify that, because it seems like it should be all of those things at once: full of lingering shots of New Orleans and the surrounding swamps, scored by John Lurie with songs by Tom Waits, both of whom star in the film as two men wrongfully imprisoned before a strange Italian man helps them find a way out.

What Down by Law is, is a film by Jim Jarmusch. In fact, it is sort of the film by Jim Jarmusch; although his second feature, Stranger Than Paradise, that won him the Camera d'Or at Cannes and made him an international figure, it was this third feature that turned him into a brand name, and confirmed the extremely characteristic style that its predecessor established. A Jarmusch film, for the uninitiated, is a very hard thing to nail down: not because it is elusive and vague, but because it is so simple to break down into readily identifiable components, and yet there seems to be no explanation for why the end result is so meditative and dreamlike.

The primary aesthetic of this film (along with much of the director's work, especially in his early years) is its casual precision. I mean something very specific with this phrase: to look at the way shots are framed, particularly in reference to their movement, and to consider the way that scenes are put next to each other, and especially to watch and listen to the non-actors performing, suggests a run-and-gun type of independent movie, for the mise en scène is extremely messy and indifferent looking. But upon a deeper analysis, none of things are at all accidental, and when for example John Lurie slumps onto a chair, he manages to position his head just exactly right in the center of the single patch of light on the far wall, in a way that cannot be an accident. Casual precision.

It's fair to say that every single incident in Down by Law - "incident" not referring to the plot, but to every camera movement, line, cut, and beat of performance - is meaningful. Example: the film opens focused on the rear fender of a car. Waits's "Jockey Full of Bourbon" plays on the soundtrack, and the camera moves to the left, across a cemetery. A few second later the shot cuts to another leftward tracking shot at the same speed, on the fronts of buildings. A few more shots, all structured more or less identically. We're seeing the many sights of New Orleans, and it seems like the film is going to be heavily invested in the specifics of that place; but then a shot comes that is static, and the music fades out. It's a shot of a pimp named Jack (Lurie) lying in bed, on the right side of the frame - just where our eye hadn't been looking, after all that leftward tracking. A brief scene plays, and the tracking shots resume - this time to the right. Then another cut, to out-of-work disc jockey Zack (Waits), on the left side of the frame. And then, the tracking shots again, moving left, and then the opening credits.

Hardly one frame of film is wasted in setting up a lot of things: the place that this is happening, and more importantly, the way that our protagonists interrupt the smooth flow of that place (both men, we quickly learn, are from other parts of the country). Down by Law will prove to be a story about how those men find themselves in a series of places and situations where they aren't supposed to be, and thus is the theme kickstarted just by a few judicious cuts early on.

(I can't help but mention: the film opens with a Waits song, and Lurie is the first character we meet. The film also closes on a Waits song, and Lurie is the last character we see. If that's a coincidence, it's a pretty goddamn compelling one).

I don't want to take the space to catalogue every moment where some fine editing took my breath away, for the whole film is basically structured around good editing. Once Jack and Zack arrive in prison, the great bulk of the film is presented in scenes that last for one uninterrupted take, showing events often separated by hours or days. That might not seem like the stuff of good editing, but whenever this pattern is interrupted, it has the impact of a hammer to the face. If a scene is cut into multiple shots, there is invariably a reason for that, for the viewer who is willing to think about it for a moment. I would like to call attention to the three fades to black in the film, each of which is followed by a hard cut from black to the new shot. In the first two cases, this ellipsis (for what else does a fade-out suggest in a movie?) happens at the moment that each man is arrested, and we next see him in jail. The third time, and I hesitate to give this away, so the rest of this paragraph is a SPOILER, occurs after the imprisoned men agree to try breaking out, with the action resuming as they run through the sewers underneath New Orleans. The one truly action-packed moment of the film therefore takes place in an ellipsis - this is the sort of moment where you either love or despise a movie, if only for its audacity.

Jack and Zack, right down to their names, are a curious sort of matched pair. Both outsiders, both set-up for the the cops, both played by musicians of a certain type of neo-beat jazz, but there is no twinning between them; they are not parts of a whole, nor do they bond as men, or even like each other very much. There's not enough difference between the two for them to function as alternating perspectives on the action. Rather, they're simply two Everymen, thrust into strange and alien places, dealing as best they can - and there are two of them for much the same reason that there is both a Rosencrantz and a Guildenstern, to emphasise that the men are normal in relative terms while the world they fight against is confused and inchoate. That world is embodied by the third man who bridges Jack and Zack, frequently confusing their names and driving most of the plot forward from the moment they arrive in jail: Roberto, an Italian tourist with little grasp of English, in the international breakthrough for the Italian comedy star Roberto Benigni. Yes, that one, but that doesn't for one instant detract from how incredibly perfect he is in the role, including his lengthy, almost completely improvised monologue in a language he functionally did not speak at the time on raising and cooking rabbits, a monologue central to the film's emotional meaning.

Roberto - the character, not the actor, although po-tay-toe po-tah-toe - is the single element that pushes the film from a fuzzy version of noir into a fascinating hybrid of noir with a fairy tale. He is the magic being that enters the plot and pushes the other men into Wonderland (he originates the break-out), and he leaves only when the men's road is more or less clear, in a practical if not a mental sense. Down by Law is a lot of things, but the first thing is a bedtime story for grown-up people, and this is Roberto's function in the narrative.

All that - I say that like I actually touched on anything but the shallowest basics - is captured by a man whose contribution was more important to the final project than perhaps even Jarmusch's: the director of photography, Robby Müller, an insanely talented cinematographer who had recently shot Paris, Texas, and would go on to a string of visual masterpieces from Barfly to Dancer in the Dark to Jarmusch's own Dead Man and Ghost Dog: The Way of the Samurai. Here, he worked with the director's beloved black and white 35mm film to create one the sharpest-looking films I have seen from the 1980s, a film that seems as sharp as reality, or even sharper than reality, for the monochrome makes everything surreal in a way; the film is both hyperfamiliar and unfamiliar. It is a perfect marriage of form and content, which may be the great triumph of Down by Law - a film in which form and content are so deeply reliant on each other that one can hardly be mentioned without bringing the other in.

What Down by Law is, is a film by Jim Jarmusch. In fact, it is sort of the film by Jim Jarmusch; although his second feature, Stranger Than Paradise, that won him the Camera d'Or at Cannes and made him an international figure, it was this third feature that turned him into a brand name, and confirmed the extremely characteristic style that its predecessor established. A Jarmusch film, for the uninitiated, is a very hard thing to nail down: not because it is elusive and vague, but because it is so simple to break down into readily identifiable components, and yet there seems to be no explanation for why the end result is so meditative and dreamlike.

The primary aesthetic of this film (along with much of the director's work, especially in his early years) is its casual precision. I mean something very specific with this phrase: to look at the way shots are framed, particularly in reference to their movement, and to consider the way that scenes are put next to each other, and especially to watch and listen to the non-actors performing, suggests a run-and-gun type of independent movie, for the mise en scène is extremely messy and indifferent looking. But upon a deeper analysis, none of things are at all accidental, and when for example John Lurie slumps onto a chair, he manages to position his head just exactly right in the center of the single patch of light on the far wall, in a way that cannot be an accident. Casual precision.

It's fair to say that every single incident in Down by Law - "incident" not referring to the plot, but to every camera movement, line, cut, and beat of performance - is meaningful. Example: the film opens focused on the rear fender of a car. Waits's "Jockey Full of Bourbon" plays on the soundtrack, and the camera moves to the left, across a cemetery. A few second later the shot cuts to another leftward tracking shot at the same speed, on the fronts of buildings. A few more shots, all structured more or less identically. We're seeing the many sights of New Orleans, and it seems like the film is going to be heavily invested in the specifics of that place; but then a shot comes that is static, and the music fades out. It's a shot of a pimp named Jack (Lurie) lying in bed, on the right side of the frame - just where our eye hadn't been looking, after all that leftward tracking. A brief scene plays, and the tracking shots resume - this time to the right. Then another cut, to out-of-work disc jockey Zack (Waits), on the left side of the frame. And then, the tracking shots again, moving left, and then the opening credits.

Hardly one frame of film is wasted in setting up a lot of things: the place that this is happening, and more importantly, the way that our protagonists interrupt the smooth flow of that place (both men, we quickly learn, are from other parts of the country). Down by Law will prove to be a story about how those men find themselves in a series of places and situations where they aren't supposed to be, and thus is the theme kickstarted just by a few judicious cuts early on.

(I can't help but mention: the film opens with a Waits song, and Lurie is the first character we meet. The film also closes on a Waits song, and Lurie is the last character we see. If that's a coincidence, it's a pretty goddamn compelling one).

I don't want to take the space to catalogue every moment where some fine editing took my breath away, for the whole film is basically structured around good editing. Once Jack and Zack arrive in prison, the great bulk of the film is presented in scenes that last for one uninterrupted take, showing events often separated by hours or days. That might not seem like the stuff of good editing, but whenever this pattern is interrupted, it has the impact of a hammer to the face. If a scene is cut into multiple shots, there is invariably a reason for that, for the viewer who is willing to think about it for a moment. I would like to call attention to the three fades to black in the film, each of which is followed by a hard cut from black to the new shot. In the first two cases, this ellipsis (for what else does a fade-out suggest in a movie?) happens at the moment that each man is arrested, and we next see him in jail. The third time, and I hesitate to give this away, so the rest of this paragraph is a SPOILER, occurs after the imprisoned men agree to try breaking out, with the action resuming as they run through the sewers underneath New Orleans. The one truly action-packed moment of the film therefore takes place in an ellipsis - this is the sort of moment where you either love or despise a movie, if only for its audacity.

Jack and Zack, right down to their names, are a curious sort of matched pair. Both outsiders, both set-up for the the cops, both played by musicians of a certain type of neo-beat jazz, but there is no twinning between them; they are not parts of a whole, nor do they bond as men, or even like each other very much. There's not enough difference between the two for them to function as alternating perspectives on the action. Rather, they're simply two Everymen, thrust into strange and alien places, dealing as best they can - and there are two of them for much the same reason that there is both a Rosencrantz and a Guildenstern, to emphasise that the men are normal in relative terms while the world they fight against is confused and inchoate. That world is embodied by the third man who bridges Jack and Zack, frequently confusing their names and driving most of the plot forward from the moment they arrive in jail: Roberto, an Italian tourist with little grasp of English, in the international breakthrough for the Italian comedy star Roberto Benigni. Yes, that one, but that doesn't for one instant detract from how incredibly perfect he is in the role, including his lengthy, almost completely improvised monologue in a language he functionally did not speak at the time on raising and cooking rabbits, a monologue central to the film's emotional meaning.

Roberto - the character, not the actor, although po-tay-toe po-tah-toe - is the single element that pushes the film from a fuzzy version of noir into a fascinating hybrid of noir with a fairy tale. He is the magic being that enters the plot and pushes the other men into Wonderland (he originates the break-out), and he leaves only when the men's road is more or less clear, in a practical if not a mental sense. Down by Law is a lot of things, but the first thing is a bedtime story for grown-up people, and this is Roberto's function in the narrative.

All that - I say that like I actually touched on anything but the shallowest basics - is captured by a man whose contribution was more important to the final project than perhaps even Jarmusch's: the director of photography, Robby Müller, an insanely talented cinematographer who had recently shot Paris, Texas, and would go on to a string of visual masterpieces from Barfly to Dancer in the Dark to Jarmusch's own Dead Man and Ghost Dog: The Way of the Samurai. Here, he worked with the director's beloved black and white 35mm film to create one the sharpest-looking films I have seen from the 1980s, a film that seems as sharp as reality, or even sharper than reality, for the monochrome makes everything surreal in a way; the film is both hyperfamiliar and unfamiliar. It is a perfect marriage of form and content, which may be the great triumph of Down by Law - a film in which form and content are so deeply reliant on each other that one can hardly be mentioned without bringing the other in.