They Shoot Pictures, Don't They? 2008 Edition - #79

By the time we get to the scene where a wealthy widower has drugged his niece, a nun-in-training wearing his dead wife's bridal grown, and is nuzzling her breasts with his face while she lies as still as a corpse, it's pretty clear that Viridiana is a sort of unique movie.

By the time, about an hour later, where a drunk homeless woman flashes a table full of beggars and cripples precisely arranged to recreate Leonardo da Vinci's Last Supper, the role of Jesus being filled by her blind husband, it's clear that Viridiana is a film by Luis Buñuel, perhaps the greatest of all cinematic iconoclasts. It's also clear why the film was denounced by the Vatican as a blasphemous assault on Catholicism, why the film was banned in Spain for its political content for 16 years, and why Buñuel's return to his home country after a 22-year exile turned into a one-film hiccup that saw him quickly return to Mexico and France.

Every time somebody talks about Viridiana, they bring up the history behind it. It's impossible to get around the fact that this is one of the most political films ever made in the West, and so I'm going to go through the boilerplate quickly: in 1936, the right-wing Francisco Franco took over the Spanish government, putting no small amount of fear in the hearts of the country's left-wing intellectuals and artists. By the end of that year, the political tensions in the country had erupted in a civil war that ended in 1939, when Franco, backed by the Vatican, established a Fascist dictatorship in the country, driving most of the left-wingers who weren't dead into exile, including the religion-baiting atheist Buñuel. During the 1950s, a series of immeasurably significant Mexican-produced films had made the director the most important Spanish-language filmmaker in the world, making it ever more likely that he would one day return to his homeland as a renowned celebrity. When that return took place in 1961, it was over the protests of the leftists who felt the director was selling out his principles. These protests were quickly silenced by the finished project: a broadside against the hypocrisy of organised religion, strident even by the standards of a man famous for poking angrily at the manifold failures of the Catholic Church.

Something about that neat little backstory offends me. Not because it's not a key component of understanding Viridiana - the film would be an infinitely lesser thing without that knowledge - but because it reduces an extraordinary cinematic treasure to the status of an op-ed piece. As anybody who's seen the film knows, it's far more than that; like most of the director's films it could be appreciate solely for the arresting & uncomfortable potency of its imagery, without any trace of a plot or theme whatsoever. And yet those images gain much of their potency from the context that explains the culture in which the film was born. Damn, how I am trapped by the necessities of history!

Buñuel claimed to hate symbolism. Therefore I am compelled to suppose that none of the apparently symbolic images in Viridiana truly are; perhaps they are merely metaphors. Metaphors that are exceptionally biting, however: a small gilt crucifix that doubles as a switchblade, or a replica crown of thorns tossed accidentally into a bonfire. Or of course the beggar's banquet that doubles as the Last Supper, scored to Handel's "Hallelujah" chorus from Messiah, in one of the film's two most iconic scenes.

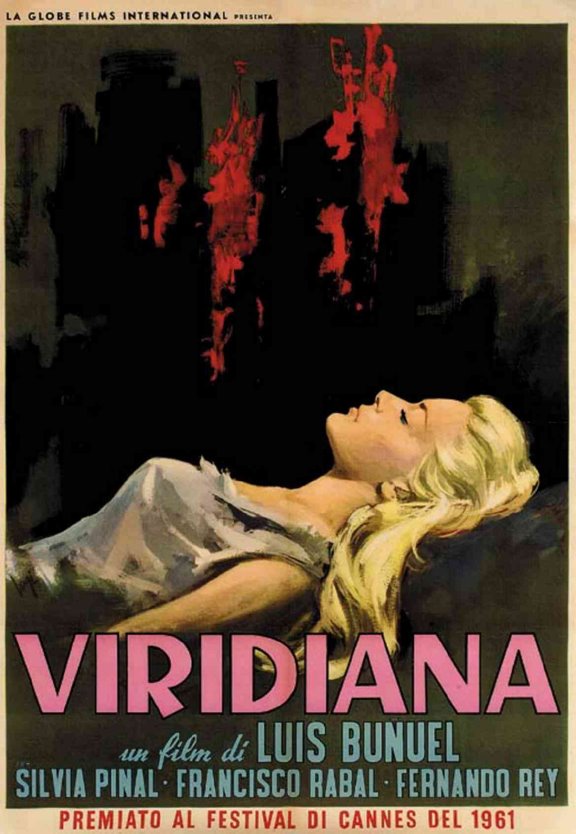

These images, all from the second of the film's two distinct parts, are all in service to its great scheme of muddying the spiritual and intellectual with the earthy and profane. The film revolves around Viridiana (the gorgeous Mexican blonde Silvia Pinal, whose sensuality is the very heart of the film), a novice only days away from taking her final vows and locking herself away from the great mass of humanity forever. Before that can happen, her Mother Superior (an uncredited actress whose name I have not been able to determine) orders her to pay one final visit at the home of her uncle, Don Jaime (Fernando Rey, in the first of his four legendary pairings with the director), who attempts to spoil her purity with his entirely secular desires; when he proves unsuccessful, he resorts to suicide.

This thirty-minute passage, revolving mostly around the sexualised representation of Pinal as the nun, starts off the film's attack on the Church's detachment from human experience: though nothing particularly untoward happens between the young woman and the old lecher, both are destroyed by religious guilt, ending in Viridiana's decision not to pursue her vows until she can shake the evil taint of sexuality that has been awakened in her mind. The second part explores how this impulse spins out after Viridiana and Don Jaime's bastard son Jorge (Francisco Rabal) both inherit the old man's fantastically large estate. Jorge wishes to turn it into a working farm and cash cow; Viridiana's more lofty goal is to turn it into a haven for paupers, who she believes need only direction to turn to a life of godliness.

The paupers, it turns out, are not so easily swayed from the pleasures of the flesh. In the film, their role is less as individual sinners or humans, but as a force of nature, indeed a force of the earth itself - they are dirtier than the other characters, in such a way that makes it seem almost like they have grown up from the ground. Buñuel is not particularly interested in condemning or approving their actions; their existence is important because they live as they will, no matter what Viridiana's noble intentions may have been. Her charity fails because of her absolute inability to understand a life force that exists outside of her literally cloistered knowledge of life, because she puts all her faith in a religious order that exists only for the rich men who control the world, and most of all because she mistakes her brief embarrassments with Don Jaime as a trial by fire that has revealed all the secrets of the secular world to her.

As with all great art, what matters isn't the theme but how the theme is expressed, and here I must claim incompetence. I can explicate Viridiana, but I could never express how overwhelming the film is, even nearly half a century later. Images that first shocked the squares in a Fascist Catholic country have lost not a hint of their ability to unsettle and amaze, and that's something I can't write about. I can only posit, and hope that this review sends at least one reader to seek the film out. It is the masterpiece of one of the giants of European cinema, like all his films a punch in the gut and a fizzy intoxication in the head, but moreso than any of them. By the time it ends, with a generic white-bread American "rock" song playing out over the prelude to a consensual rape, it's ceased to be a political movie, and art film, a comedy, a satire. It is the soul of cinema streamed into the viewer like the voice of a non-existent God.

By the time, about an hour later, where a drunk homeless woman flashes a table full of beggars and cripples precisely arranged to recreate Leonardo da Vinci's Last Supper, the role of Jesus being filled by her blind husband, it's clear that Viridiana is a film by Luis Buñuel, perhaps the greatest of all cinematic iconoclasts. It's also clear why the film was denounced by the Vatican as a blasphemous assault on Catholicism, why the film was banned in Spain for its political content for 16 years, and why Buñuel's return to his home country after a 22-year exile turned into a one-film hiccup that saw him quickly return to Mexico and France.

Every time somebody talks about Viridiana, they bring up the history behind it. It's impossible to get around the fact that this is one of the most political films ever made in the West, and so I'm going to go through the boilerplate quickly: in 1936, the right-wing Francisco Franco took over the Spanish government, putting no small amount of fear in the hearts of the country's left-wing intellectuals and artists. By the end of that year, the political tensions in the country had erupted in a civil war that ended in 1939, when Franco, backed by the Vatican, established a Fascist dictatorship in the country, driving most of the left-wingers who weren't dead into exile, including the religion-baiting atheist Buñuel. During the 1950s, a series of immeasurably significant Mexican-produced films had made the director the most important Spanish-language filmmaker in the world, making it ever more likely that he would one day return to his homeland as a renowned celebrity. When that return took place in 1961, it was over the protests of the leftists who felt the director was selling out his principles. These protests were quickly silenced by the finished project: a broadside against the hypocrisy of organised religion, strident even by the standards of a man famous for poking angrily at the manifold failures of the Catholic Church.

Something about that neat little backstory offends me. Not because it's not a key component of understanding Viridiana - the film would be an infinitely lesser thing without that knowledge - but because it reduces an extraordinary cinematic treasure to the status of an op-ed piece. As anybody who's seen the film knows, it's far more than that; like most of the director's films it could be appreciate solely for the arresting & uncomfortable potency of its imagery, without any trace of a plot or theme whatsoever. And yet those images gain much of their potency from the context that explains the culture in which the film was born. Damn, how I am trapped by the necessities of history!

Buñuel claimed to hate symbolism. Therefore I am compelled to suppose that none of the apparently symbolic images in Viridiana truly are; perhaps they are merely metaphors. Metaphors that are exceptionally biting, however: a small gilt crucifix that doubles as a switchblade, or a replica crown of thorns tossed accidentally into a bonfire. Or of course the beggar's banquet that doubles as the Last Supper, scored to Handel's "Hallelujah" chorus from Messiah, in one of the film's two most iconic scenes.

These images, all from the second of the film's two distinct parts, are all in service to its great scheme of muddying the spiritual and intellectual with the earthy and profane. The film revolves around Viridiana (the gorgeous Mexican blonde Silvia Pinal, whose sensuality is the very heart of the film), a novice only days away from taking her final vows and locking herself away from the great mass of humanity forever. Before that can happen, her Mother Superior (an uncredited actress whose name I have not been able to determine) orders her to pay one final visit at the home of her uncle, Don Jaime (Fernando Rey, in the first of his four legendary pairings with the director), who attempts to spoil her purity with his entirely secular desires; when he proves unsuccessful, he resorts to suicide.

This thirty-minute passage, revolving mostly around the sexualised representation of Pinal as the nun, starts off the film's attack on the Church's detachment from human experience: though nothing particularly untoward happens between the young woman and the old lecher, both are destroyed by religious guilt, ending in Viridiana's decision not to pursue her vows until she can shake the evil taint of sexuality that has been awakened in her mind. The second part explores how this impulse spins out after Viridiana and Don Jaime's bastard son Jorge (Francisco Rabal) both inherit the old man's fantastically large estate. Jorge wishes to turn it into a working farm and cash cow; Viridiana's more lofty goal is to turn it into a haven for paupers, who she believes need only direction to turn to a life of godliness.

The paupers, it turns out, are not so easily swayed from the pleasures of the flesh. In the film, their role is less as individual sinners or humans, but as a force of nature, indeed a force of the earth itself - they are dirtier than the other characters, in such a way that makes it seem almost like they have grown up from the ground. Buñuel is not particularly interested in condemning or approving their actions; their existence is important because they live as they will, no matter what Viridiana's noble intentions may have been. Her charity fails because of her absolute inability to understand a life force that exists outside of her literally cloistered knowledge of life, because she puts all her faith in a religious order that exists only for the rich men who control the world, and most of all because she mistakes her brief embarrassments with Don Jaime as a trial by fire that has revealed all the secrets of the secular world to her.

As with all great art, what matters isn't the theme but how the theme is expressed, and here I must claim incompetence. I can explicate Viridiana, but I could never express how overwhelming the film is, even nearly half a century later. Images that first shocked the squares in a Fascist Catholic country have lost not a hint of their ability to unsettle and amaze, and that's something I can't write about. I can only posit, and hope that this review sends at least one reader to seek the film out. It is the masterpiece of one of the giants of European cinema, like all his films a punch in the gut and a fizzy intoxication in the head, but moreso than any of them. By the time it ends, with a generic white-bread American "rock" song playing out over the prelude to a consensual rape, it's ceased to be a political movie, and art film, a comedy, a satire. It is the soul of cinema streamed into the viewer like the voice of a non-existent God.