Family ties

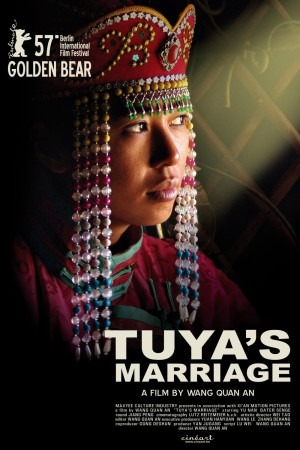

The advertisements for 2007's Berlinale Golden Bear winner, Tuya's Marriage - and is there anything so ubiquitous as the ads for a two-year-old foreign film on the art house circuit? - all make the claim that it's a warm study of human resilience. This is at best misleadingly true; the particular manner that the film studies resilience is through the observation, "no matter how much crap we throw at this poor woman, she just won't die!

Maybe that's a touch snarky, but I think the point is made. What keeps the film from out-and-out miserabilism is a deadpan comic tone, a subtly brilliant command of cinematic language, and the extraordinarily gifted actress at its center. And ultimately, it is humanist in its own hard-won fashion, although calling it "warm" is a gross exaggeration. The plot is hardly nice or uplifting, and even the imagery feels a bit chilly, just as the Mongolian steppes ought to feel, even in what passes for summer there.

Above all things, this film is about a crisis in the life of Tuya (Nan Yu), a shepherd who is the sole support for her children and her disabled husband. After an accident injures her back, "sole support" turns into "no support" and the isolated community she lives in urges her to divorce her husband Bater (played by a Mongolian non-actor named...Bater. You may assume that this formula is true for every other character in the film) and find a new husband with the means to support her, and her children, and her beloved, disabled presumptive ex-husband. A collection of eccentrics come a-courting, leaving Tuya with a whole lot of bad choices in a situation with no realistically pleasing solution.

That covers about as much plot as the film has, although by the time this particular conflict has mostly wrapped itself up, there is still a good amount of the running time left to go. That's because Tuya's Marriage is only incidentally about drama, and much more about the beats of human life in a remote place mostly untouched by what we might like to call civilization. Which isn't to say that it's just a mere ethnography, though that certainly comes into play. Rather, this is a film about a very specific group of people whose existence is tied to a specific way of life on a specific patch of land. Inasmuch as it focuses on the hows and whys of a Mongolian shepherd's life, it's only because being a Mongolian shepherd is the only frame in which Tuya can be understood. One might as well call a Woody Allen film an ethnography of New York Jewishness.

Director Wang Quan-An, a Sixth Generation filmmaker almost totally unknown in the United States after three features, has a remarkable sense for the way to dramatise the land. At first, the style of Tuya's Marriage seems completely unremarkable, just the usual assortment of wide shots outdoors and closer shots inside, with very significant close-ups on the principles' faces. But as the film progresses, he reveals more and more of what he's really all about: the first time we see a high-angle shot of Tuya walking down a dirt road, it hardly registers as anything more than an establishing shot, but the fourth and fifth time we see the same action from the same shot, it has begun to take on the aspect of ritual, a repetitive but characteristic action that must be undertaken for Tuya to remain Tuya. And late in the film, when the action briefly adjusts to the "Big City," Wang's method is even more clear: life in the village is simple and familiar, and while it's inordinately difficult, it's unchallenging. When modernity intervenes, as it does early on in the form of a wrecked motorbike and later on in the form of buildings and cars, it's unexpected and it doesn't fit into the film's aesthetic any more than it fits into the characters' lives (this could be interpreted as that old cliché, life in the rural country is nicer than life in the city and it's a shame that progress moves onward, but it somehow feels less programmatic than that. Then again, this is a Chinese film, so it's hard to tell).

On its own merits, this would be a fine and compelling work about how people live; it is pushed to the next level by Nan Yu's extraordinary treatment of the character of Tuya, making this not just a general tale of humanity but an arresting depiction of psychology. The easiest thing would be to present Tuya as a put-upon saint, and I have a hard time imagining this movie getting made in the West in any other way. But that's not what Wang and Nan are aiming for: Tuya is certainly a likable woman, but hardly a uniformly pleasant one. She's cantankerous and blunt, and even in her injury she maintains a degree of control over her life that absolutely prevents her from seeming like an object of pity. She is that unbreakable human life force that we've been promised, and only the film's opening and closing scenes call that into question at all, although those scenes are filmed in a way that presents Tuya as frustrated instead of truly distressed.

All in all, Tuya's Marriage is a lovely example of a very wonderful kind of movie: it seems very good but very minor as you're watching it, but it latches onto your brain and won't move. It's probably not a masterpiece, but it is an deniable achievement. Its emotions are not grand and sweeping, but they are absolutely sincere.

8/10

Maybe that's a touch snarky, but I think the point is made. What keeps the film from out-and-out miserabilism is a deadpan comic tone, a subtly brilliant command of cinematic language, and the extraordinarily gifted actress at its center. And ultimately, it is humanist in its own hard-won fashion, although calling it "warm" is a gross exaggeration. The plot is hardly nice or uplifting, and even the imagery feels a bit chilly, just as the Mongolian steppes ought to feel, even in what passes for summer there.

Above all things, this film is about a crisis in the life of Tuya (Nan Yu), a shepherd who is the sole support for her children and her disabled husband. After an accident injures her back, "sole support" turns into "no support" and the isolated community she lives in urges her to divorce her husband Bater (played by a Mongolian non-actor named...Bater. You may assume that this formula is true for every other character in the film) and find a new husband with the means to support her, and her children, and her beloved, disabled presumptive ex-husband. A collection of eccentrics come a-courting, leaving Tuya with a whole lot of bad choices in a situation with no realistically pleasing solution.

That covers about as much plot as the film has, although by the time this particular conflict has mostly wrapped itself up, there is still a good amount of the running time left to go. That's because Tuya's Marriage is only incidentally about drama, and much more about the beats of human life in a remote place mostly untouched by what we might like to call civilization. Which isn't to say that it's just a mere ethnography, though that certainly comes into play. Rather, this is a film about a very specific group of people whose existence is tied to a specific way of life on a specific patch of land. Inasmuch as it focuses on the hows and whys of a Mongolian shepherd's life, it's only because being a Mongolian shepherd is the only frame in which Tuya can be understood. One might as well call a Woody Allen film an ethnography of New York Jewishness.

Director Wang Quan-An, a Sixth Generation filmmaker almost totally unknown in the United States after three features, has a remarkable sense for the way to dramatise the land. At first, the style of Tuya's Marriage seems completely unremarkable, just the usual assortment of wide shots outdoors and closer shots inside, with very significant close-ups on the principles' faces. But as the film progresses, he reveals more and more of what he's really all about: the first time we see a high-angle shot of Tuya walking down a dirt road, it hardly registers as anything more than an establishing shot, but the fourth and fifth time we see the same action from the same shot, it has begun to take on the aspect of ritual, a repetitive but characteristic action that must be undertaken for Tuya to remain Tuya. And late in the film, when the action briefly adjusts to the "Big City," Wang's method is even more clear: life in the village is simple and familiar, and while it's inordinately difficult, it's unchallenging. When modernity intervenes, as it does early on in the form of a wrecked motorbike and later on in the form of buildings and cars, it's unexpected and it doesn't fit into the film's aesthetic any more than it fits into the characters' lives (this could be interpreted as that old cliché, life in the rural country is nicer than life in the city and it's a shame that progress moves onward, but it somehow feels less programmatic than that. Then again, this is a Chinese film, so it's hard to tell).

On its own merits, this would be a fine and compelling work about how people live; it is pushed to the next level by Nan Yu's extraordinary treatment of the character of Tuya, making this not just a general tale of humanity but an arresting depiction of psychology. The easiest thing would be to present Tuya as a put-upon saint, and I have a hard time imagining this movie getting made in the West in any other way. But that's not what Wang and Nan are aiming for: Tuya is certainly a likable woman, but hardly a uniformly pleasant one. She's cantankerous and blunt, and even in her injury she maintains a degree of control over her life that absolutely prevents her from seeming like an object of pity. She is that unbreakable human life force that we've been promised, and only the film's opening and closing scenes call that into question at all, although those scenes are filmed in a way that presents Tuya as frustrated instead of truly distressed.

All in all, Tuya's Marriage is a lovely example of a very wonderful kind of movie: it seems very good but very minor as you're watching it, but it latches onto your brain and won't move. It's probably not a masterpiece, but it is an deniable achievement. Its emotions are not grand and sweeping, but they are absolutely sincere.

8/10