Icons of cinema

A review requested by André Robichaud, with thanks for contributing to the Second Quinquennial Antagony & Ecstasy ACS Fundraiser.

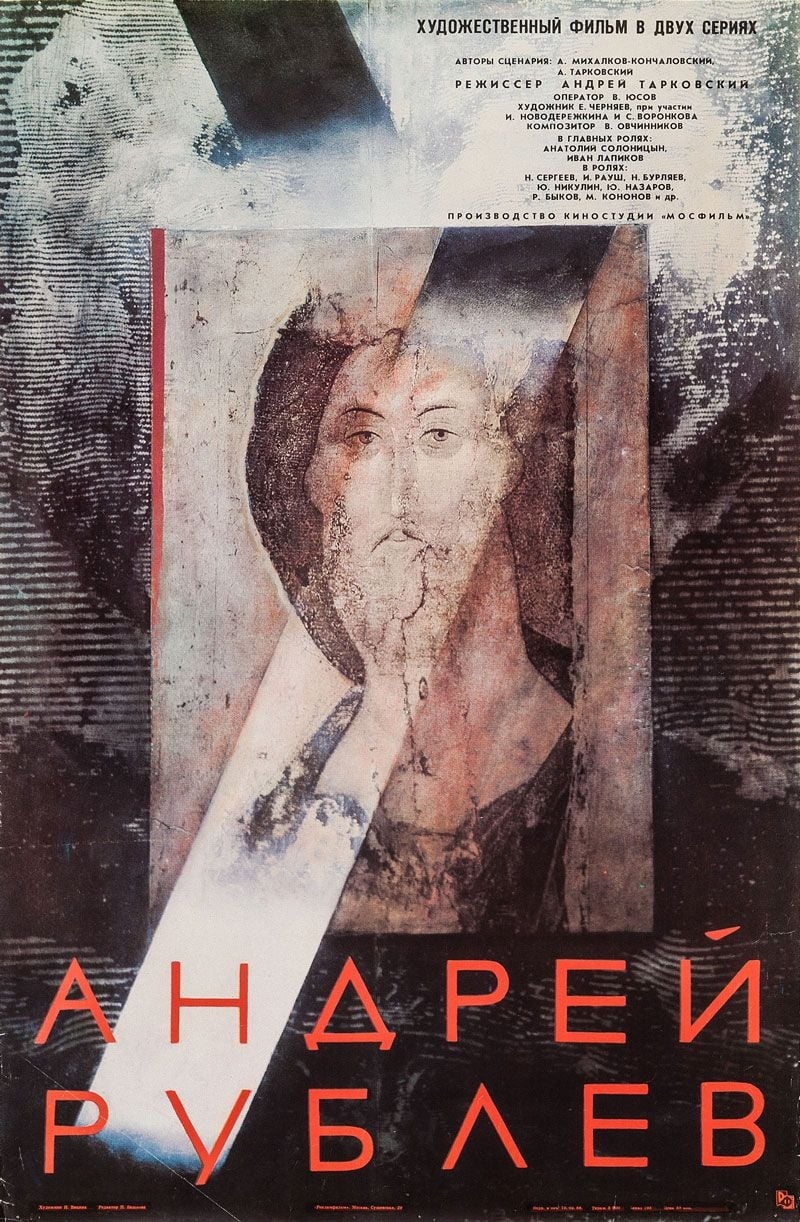

The apparent subject of Soviet director Andrei Tarkovsky's second feature, Andrei Rublev, is indicated right in the title: it's a story of the life of the most renowned painter of icons in medieval Russia, Andrei Rublev (Anatoly Solonitsyn). Which is not, as film loglines go, a lie - but it is painfully reductive. At a minimum, the film also uses Andrei's life as a surrogate for examining the history of Russia in the first quarter of the 15th Century, during which time the Grand Duchy of Moscow began to wrest control from the Mongol Tatars, thus setting the stage for the country we now refer to as "Russia" to come into existence under one government. It is a story of how Orthodox Christianity was a driving engine of proto-Russian identity, and of the tense relationship between artists driven by their need to communicate spiritual truths, and totalitarian governments who saw no value - or were outright threatened - by those artists. And what do you think, but the Soviet government was leery of the movie, sending Tarkovsky to the editing room twice, shortening a 205-minute version of the film (the one universally available now) to 190 minutes, thence to 186 (the version Tarkovsky officially claimed to prefer), for its solitary screening in 1966; it was this version that was notoriously shown at 4:00 in the morning on the last day of the 1969 Cannes Film Festival.

Taking the film as a historical argument about religion, art, and psychology that became yet another one of the many films in the second half of the 20th Century that ran afoul of Communist government censors isn't giving it enough credit either. In its gargantuan, three hour and 25-minute grandeur (whatever Tarkovsky might have said later, I couldn't imagine losing one frame of it), this is the one film, if ever there was such a film, that strikes me as truly being about the whole experience of life. Told in a prologue, eight parts, and a non-narrative epilogue, the film finds a setting to address virtually every facet of the human experience, using its radical narrative structure and mise en scène to express Deep Ideas about the relationship between God and the individual, the individual and society, society and history, history and God, and it does this elliptically, symbolically, and implicitly rather than at any point taking the viewer's hand to say "here's what I think about these very important subjects". It is one of the essential films ever made, and also, perhaps the apotheosis of the great tradition of Russian literature of ideas, using the medium of cinema to explore its profundities in a more glancing, complex manner than even the best prose of the 19th Century could muster.

In order to get at this grand, sprawling content, Tarkovsky and his collaborators - co-writer Andrei Konchalovsky, cinematographer Vadim Yusov, production designer Evgeniy Chernyaev, costumers Maya Abar-Baranovskaya and Lidiya Novi, and the three-person editing team of Tatyana Egorycheva, Lyudmila Feyginova, and Olga Shevkunenko being among the key names to know - worked to the goal, not of fleshing out a narrative (talking about Andrei Rublev in terms of its plot is faintly impossible), but of building a complete, immersive world, which is then filled with symbolic objects rather than events. But they're also actually events. It's hard to describe the feeling of it. The film's opening, for example, is of a man played by Nikolai Glazkov prepping a hot air balloon and launching it just in front of a mob trying to tear him down. After a few moments, he crashes. And that, like, happens.We're not given any reason to doubt the literal truth of what's happening, particularly given its succulent physicality.

But at the same time, this isn't "about" a hot air balloon crashing - it is about the desire to rise above while being pulled down, and about human overreach ending in disaster, but also the way that life continues on despite individual failures. For it is followed by the first of the film's many horses, a symbol of the greatest importance in Andrei Rublev's universe: horses represent the animal instinct to survive, the life force if we want to be more upbeat about it. And the film, despite being 3.5 hours of suffering in medieval Russia, is perfectly willing to encourage our being upbeat: it is about surviving and finding joy as much as it is about being beaten and bloodied by the onslaught of history. In fact, its final, longest, and best sequence, in which a giant bell is cast over the course of a year is all but explicitly a tribute to the human ability to endure and triumph against all odds including self doubt. It sounds ludicrous, and when I first saw the movie it was as much out of a sense of baffled curiosity why the hell a movie would see fit to end with a lengthy sequence about medieval bell-casting techniques as because I expected for it to be even slightly interesting. But it is gripping: as human drama, while we watch young Boriska (Nikolai Burlyayev) find himself suddenly thrust into a position of responsibility and authority that he's not prepared for, and finding the fortitude to survive it; and as cinema, for the film's overall aesthetic reaches its finest expression in this sequence.

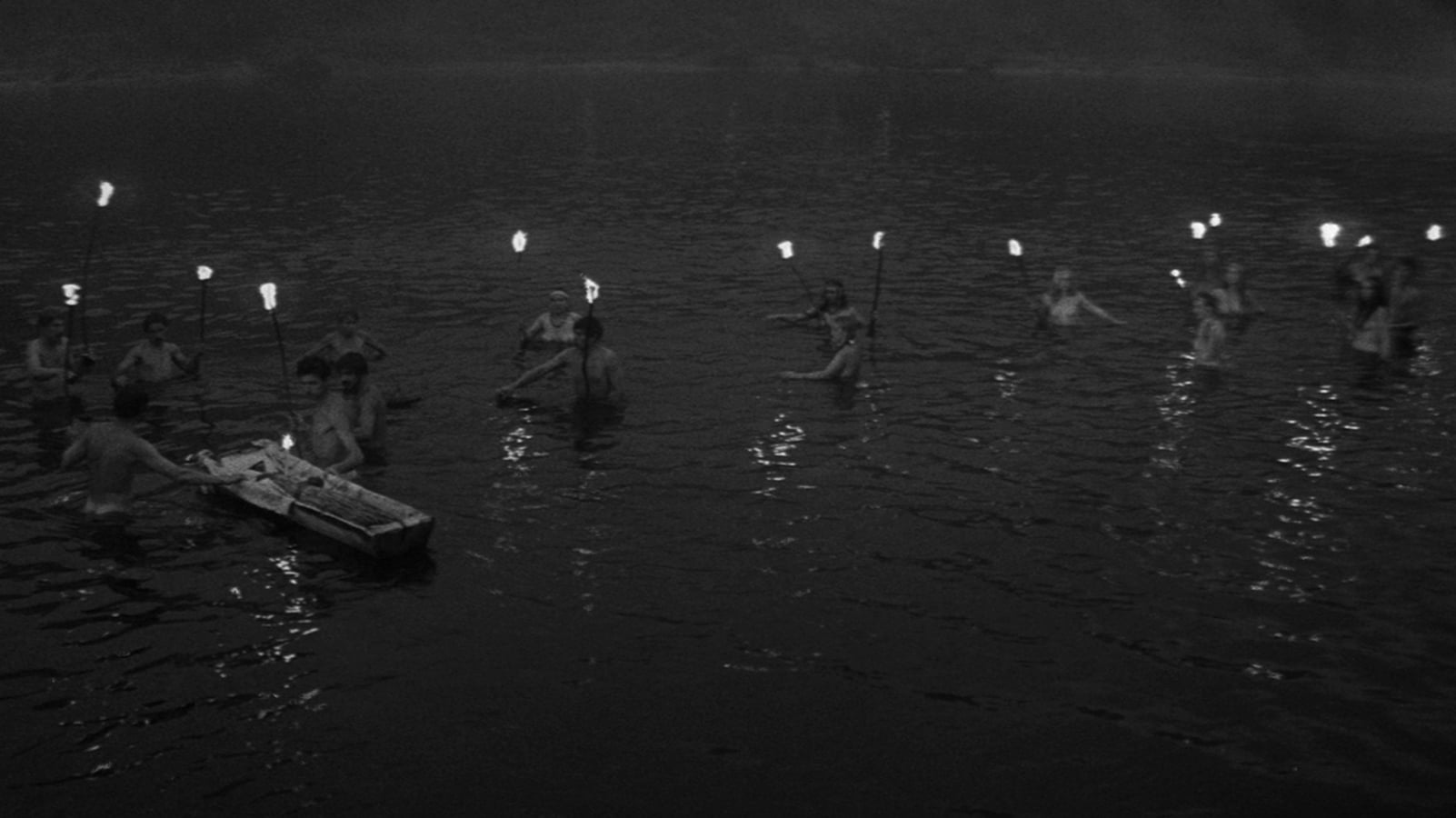

That aesthetic deserves plenty of explication, because it is maybe the most important thing about Andrei Rublev. This is, more or less, the spring from which all of "slow cinema" emerges: long takes, frequently so wide that individual humans fall into a blur, with the camera set as restrained, unblinking observer. Watching the film, one starts to feel that each frame is inspired by painting, yet Tarkovsky and Yusov don't take the expected route of basing their style in Andrei's own icon painting - in fact, if there's any specific tradition of art that the film evokes, it's the pageant-like art of medieval France and England, emphasising and exploiting the width of the anamorphic widescreen frame. I'd say that the film is made out of tableaux, if that didn't suggest a certain posed, static quality that's nothing like the unconstrained movement onscreen.

What this all means, in any case, it that the film does greater work than anything else I can name of simultaneously: A) presenting medieval life in full detail, lingering steadily within sets to capture the full texture and rhythm of a centuries-dead world, while B) being so aware of the organic human component of that life that it feels like we've been dropped squarely in the center of a vibrant, tactile, living world. The only film that comes even close to matching this is Ingmar Bergman's earlier The Seventh Seal, which has a much smaller scope focused on a much less naturalistic scenario, and isn't as extraordinary in its reach - Bergman's interest in death and suffering starts and ends in Scandinavian Lutheranism, while Tarkovsky's study of belief in goodness and faith driving a man's life starts in Russian Orthodoxy, but moves beyond theism or any other specific belief system by the end, in its wide-ranging consideration of what gives meaning to human life and why.

The film is at once stately and lively, glacially paced over its 3.5 hours but so quick in its moments that it's preposterous how quickly it moves towards its meditative finale (a reel in full color, studying in wide and close shots the paintings that are Andrei's legacy). It evolves along the way: the first half of the film is full of greatness, but the second half is on an entirely different level, one unmatched by anything else in world cinema: the bell-casting passage, like a preceding sequence that finds the city of Vladimir sacked by Tatars, could be separated from the movie entirely and presented as a self-contained short, and either of those shorts would make a strong claim towards being one of the key texts of artistic cinema. The Tatar sequence, "The Raid", is a particularly extraordinary case study in everything that makes Andrei Rublev a masterpiece: its depiction, in the script, of the individual being affected by faceless collective history is perfectly complimented by the way that wide shots full of activity allow us to simultaneously appreciated specific character beats against the backdrop of crowded tumult and violence (this is also the scene that makes it impossible to issue an unhesitating blanket recommendation for the film: an actual cow is actually set on fire and tears off camera, where I hope it was doused. But still, the movie contains unsimulated bovine torture). The contrasts that the filmmakers are able to pack into individual shots are incredible and deeply moving: a shot of snow and ash falling onto a smoking church - into which, of course, a horse wanders - is one of the highest moments in any film from the 1960s, or ever.

It is entirely possible that one could eventually exhaust Andrei Rublev, but I don't know what that would take. There's simply so much in it, expressed in such dense visuals and under-stressed performances and elliptical thought. And hacking through all that density is among the most rewarding experiences I have ever had in my life of watching films. If cinephilia has a literal holy text, to be referred to and examined in times of joy and stress and sorrow, it is this.

The apparent subject of Soviet director Andrei Tarkovsky's second feature, Andrei Rublev, is indicated right in the title: it's a story of the life of the most renowned painter of icons in medieval Russia, Andrei Rublev (Anatoly Solonitsyn). Which is not, as film loglines go, a lie - but it is painfully reductive. At a minimum, the film also uses Andrei's life as a surrogate for examining the history of Russia in the first quarter of the 15th Century, during which time the Grand Duchy of Moscow began to wrest control from the Mongol Tatars, thus setting the stage for the country we now refer to as "Russia" to come into existence under one government. It is a story of how Orthodox Christianity was a driving engine of proto-Russian identity, and of the tense relationship between artists driven by their need to communicate spiritual truths, and totalitarian governments who saw no value - or were outright threatened - by those artists. And what do you think, but the Soviet government was leery of the movie, sending Tarkovsky to the editing room twice, shortening a 205-minute version of the film (the one universally available now) to 190 minutes, thence to 186 (the version Tarkovsky officially claimed to prefer), for its solitary screening in 1966; it was this version that was notoriously shown at 4:00 in the morning on the last day of the 1969 Cannes Film Festival.

Taking the film as a historical argument about religion, art, and psychology that became yet another one of the many films in the second half of the 20th Century that ran afoul of Communist government censors isn't giving it enough credit either. In its gargantuan, three hour and 25-minute grandeur (whatever Tarkovsky might have said later, I couldn't imagine losing one frame of it), this is the one film, if ever there was such a film, that strikes me as truly being about the whole experience of life. Told in a prologue, eight parts, and a non-narrative epilogue, the film finds a setting to address virtually every facet of the human experience, using its radical narrative structure and mise en scène to express Deep Ideas about the relationship between God and the individual, the individual and society, society and history, history and God, and it does this elliptically, symbolically, and implicitly rather than at any point taking the viewer's hand to say "here's what I think about these very important subjects". It is one of the essential films ever made, and also, perhaps the apotheosis of the great tradition of Russian literature of ideas, using the medium of cinema to explore its profundities in a more glancing, complex manner than even the best prose of the 19th Century could muster.

In order to get at this grand, sprawling content, Tarkovsky and his collaborators - co-writer Andrei Konchalovsky, cinematographer Vadim Yusov, production designer Evgeniy Chernyaev, costumers Maya Abar-Baranovskaya and Lidiya Novi, and the three-person editing team of Tatyana Egorycheva, Lyudmila Feyginova, and Olga Shevkunenko being among the key names to know - worked to the goal, not of fleshing out a narrative (talking about Andrei Rublev in terms of its plot is faintly impossible), but of building a complete, immersive world, which is then filled with symbolic objects rather than events. But they're also actually events. It's hard to describe the feeling of it. The film's opening, for example, is of a man played by Nikolai Glazkov prepping a hot air balloon and launching it just in front of a mob trying to tear him down. After a few moments, he crashes. And that, like, happens.We're not given any reason to doubt the literal truth of what's happening, particularly given its succulent physicality.

But at the same time, this isn't "about" a hot air balloon crashing - it is about the desire to rise above while being pulled down, and about human overreach ending in disaster, but also the way that life continues on despite individual failures. For it is followed by the first of the film's many horses, a symbol of the greatest importance in Andrei Rublev's universe: horses represent the animal instinct to survive, the life force if we want to be more upbeat about it. And the film, despite being 3.5 hours of suffering in medieval Russia, is perfectly willing to encourage our being upbeat: it is about surviving and finding joy as much as it is about being beaten and bloodied by the onslaught of history. In fact, its final, longest, and best sequence, in which a giant bell is cast over the course of a year is all but explicitly a tribute to the human ability to endure and triumph against all odds including self doubt. It sounds ludicrous, and when I first saw the movie it was as much out of a sense of baffled curiosity why the hell a movie would see fit to end with a lengthy sequence about medieval bell-casting techniques as because I expected for it to be even slightly interesting. But it is gripping: as human drama, while we watch young Boriska (Nikolai Burlyayev) find himself suddenly thrust into a position of responsibility and authority that he's not prepared for, and finding the fortitude to survive it; and as cinema, for the film's overall aesthetic reaches its finest expression in this sequence.

That aesthetic deserves plenty of explication, because it is maybe the most important thing about Andrei Rublev. This is, more or less, the spring from which all of "slow cinema" emerges: long takes, frequently so wide that individual humans fall into a blur, with the camera set as restrained, unblinking observer. Watching the film, one starts to feel that each frame is inspired by painting, yet Tarkovsky and Yusov don't take the expected route of basing their style in Andrei's own icon painting - in fact, if there's any specific tradition of art that the film evokes, it's the pageant-like art of medieval France and England, emphasising and exploiting the width of the anamorphic widescreen frame. I'd say that the film is made out of tableaux, if that didn't suggest a certain posed, static quality that's nothing like the unconstrained movement onscreen.

What this all means, in any case, it that the film does greater work than anything else I can name of simultaneously: A) presenting medieval life in full detail, lingering steadily within sets to capture the full texture and rhythm of a centuries-dead world, while B) being so aware of the organic human component of that life that it feels like we've been dropped squarely in the center of a vibrant, tactile, living world. The only film that comes even close to matching this is Ingmar Bergman's earlier The Seventh Seal, which has a much smaller scope focused on a much less naturalistic scenario, and isn't as extraordinary in its reach - Bergman's interest in death and suffering starts and ends in Scandinavian Lutheranism, while Tarkovsky's study of belief in goodness and faith driving a man's life starts in Russian Orthodoxy, but moves beyond theism or any other specific belief system by the end, in its wide-ranging consideration of what gives meaning to human life and why.

The film is at once stately and lively, glacially paced over its 3.5 hours but so quick in its moments that it's preposterous how quickly it moves towards its meditative finale (a reel in full color, studying in wide and close shots the paintings that are Andrei's legacy). It evolves along the way: the first half of the film is full of greatness, but the second half is on an entirely different level, one unmatched by anything else in world cinema: the bell-casting passage, like a preceding sequence that finds the city of Vladimir sacked by Tatars, could be separated from the movie entirely and presented as a self-contained short, and either of those shorts would make a strong claim towards being one of the key texts of artistic cinema. The Tatar sequence, "The Raid", is a particularly extraordinary case study in everything that makes Andrei Rublev a masterpiece: its depiction, in the script, of the individual being affected by faceless collective history is perfectly complimented by the way that wide shots full of activity allow us to simultaneously appreciated specific character beats against the backdrop of crowded tumult and violence (this is also the scene that makes it impossible to issue an unhesitating blanket recommendation for the film: an actual cow is actually set on fire and tears off camera, where I hope it was doused. But still, the movie contains unsimulated bovine torture). The contrasts that the filmmakers are able to pack into individual shots are incredible and deeply moving: a shot of snow and ash falling onto a smoking church - into which, of course, a horse wanders - is one of the highest moments in any film from the 1960s, or ever.

It is entirely possible that one could eventually exhaust Andrei Rublev, but I don't know what that would take. There's simply so much in it, expressed in such dense visuals and under-stressed performances and elliptical thought. And hacking through all that density is among the most rewarding experiences I have ever had in my life of watching films. If cinephilia has a literal holy text, to be referred to and examined in times of joy and stress and sorrow, it is this.