They Shoot Pictures, Don't They? 2008 Edition - #276

In January, I began this "Top 1000" project with The Leopard, a film about the declining fortunes of the Italian nobility during the Risorgimento. It was the first film I'd seen by director Luchino Visconti, I observed, and a damn fine introduction; enough so that in the months since then, I've become quite the little Visconti whore. From the metaphoric neo-realism of Rocco and His Brothers to the lurid theatrics of The Damned, I've been delighted to find with every new film that the canon of the long-dead filmmaker is a parade of the unexpected and the surprising, every film stretching some new muscle and reveling in an entirely new idiom while still unmistakably bearing the mark of a Visconti film. Which makes it at least a touch ironic that for my second Visconti review of the year, I've selected a film about the declining fortunes of the Italian nobility during the Risorgimento.

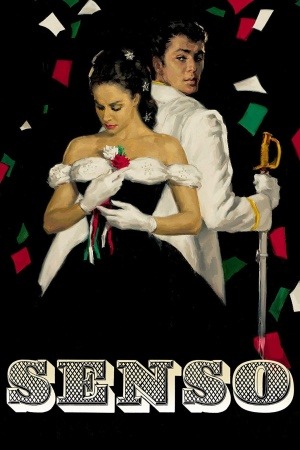

To be fair, besides their setting and the social class of their protagonists, 1954's Senso and 1963's The Leopard don't have much in common as stories or as films, in keeping with the director's remarkable ability as a stylistic chameleon. Whereas the latter work is a sober, serious epic, the earlier one is a wild melodrama, a tearjerker like Douglas Sirk might have made if only he'd had a bit more of an eye towards the historical. As well it might be, given that it's essentially Visconti's stab at making a movie of an opera. All the same elements are there: outsized emotions, ludicrous plot twists, and costumes so luscious that if you wanted to, you good just gawk at them the whole time and still have a pretty swell evening.

The relationship between Senso and opera couldn't possibly be made any clearer than it is: the very first shot of the film is of a production of Verdi's Il trovatore at La Fenice. Setting aside the matter of using that highly metaphorical opera to begin a film about the Risorgimento (think of an American Civil War movie opening with a stage production of Uncle Tom's Cabin, and you're in the right ballpark) as better suited to the strengths of an Italian history buff, the production we see is a monumentally lavish affair, though perhaps no more lavish than would have actually been presented in Venice in the 1860s. That being said, we don't get to see too much of it, and rightly so, for as any 19th Century Italian could tell you, the reason for going to the opera is to people-watch and gossip, and we have plenty of both to attend to.

The performance ends with a demonstration protesting the occupying Austrian army, held by a radical group let by Roberto Ussoni (Massimo Girotti). Among those attending the opera is Ussoni's cousin, the Contessa Livia Serpieri (Alida Valli, delectable as always) and her husband (Heinz Moog), a collaborator with the Austrians, here embodied by the wicked Lieutenant Franz Mahler (American actor Farley Granger, early in the European phase of his career). That information all gets doled out to us in bits and pieces, nestled in with a great deal of whispered gossip, and the whole process is shot by Visconti in a tremendously exciting series of quick-moving tracking shots. The director's use of camera movement is always quite exemplary, from the stately tracks that emphasise physical geometry in The Leopard to the tensely-composed static shots that make up most of Death in Venice. But I don't believe that I have yet seen a film of his with such a freewheeling camera as we see in Senso, especially in these opening minutes; the way it races from place to place is a perfect match for the breathless chatter and confusion that it documents in this first scene.

Naturally, there comes to be a plot, and it's a twisty thing: the patriotic Livia, offended by her husband's mewling complacency, finds herself falling in love with a more forceful example of manhood, and it just so happens to be Mahler (which, I suppose, might just be a metaphor in itself). As far as the story goes, that's really all you need: for most of the film's two hours, the contessa and Mahler tryst in her giant home, or she spends her time trying to figure out how to dump her crappy spouse and prolong her country's occupation long enough to make a new home with her Austrian paramour, all while steadfastly ignoring the increasingly obvious signs that he's planning on dicking her over. The delight (as is usually the case in opera) isn't in seeing what happens, but enjoying all the moments along the way.

And, as is usually the case in opera, the chief of all delights is the performance by the woman in the center of it all. Valli is hardly a household name in the United States, known (if at all) primarily for playing the femme fatale in Carol Reed's The Third Man. Which, make no mistake, is a great thing to know her for, typifying what makes her so irresistible in so many things: she's one of the great exotic Europeans who postively ooze sex and mystery just by standing there, irrespective of quibbly little things like "acting ability" (think Claudia Cardinale, or more recently, Asia Argento). Frankly, I don't know that Valli is a good or bad actress per se, but I do know that she is magnetic - if she is onscreen, you are watching her. That's a far more important thing than something so pedestrian as acting. I've personally never seen her in a role of such large size as Livia, nor one that plays so well to her strengths; and the results are incandesent. Senso triumphs on the strength of its leading lady's presence, a glamorous and passionate eye for the whole messy hurricane of betrayal and lust to whirl around.

The rest of the film's pleasures are similarly earthy, rather than esoteric. Like The Leopard after it, Senso looks simply ravishing, not just in the contessa's rich gowns that swirl around like a dancer's veils, but also the set design, focusing on the gilt and detail of the nobility, with just a touch of decay around the edges to remind us of how depraved and corrupt all of it is. Meanwhile, Visconti's camera, as wielded by cinematographer G.R. Aldo in his last film after a career including stints with De Sica and Welles, captures it all with a flair for the dramatic in composition and in movement, all in some of the thickest Technicolor I've ever seen outside of a Hollywood studio production.

For those who require such things, there's a healthy dose of Importance to all of this, most of it to do with the film's historic-political elements, but my needs at the moment I saw it were well-served by the sensual marvels on display. There's precious damn little to the film that's subtle, but remember: opera. Subtlety matter less than being bowled over in lusciousness sometimes, and you'd have to go very far to find a more luscious movie than this one.

To be fair, besides their setting and the social class of their protagonists, 1954's Senso and 1963's The Leopard don't have much in common as stories or as films, in keeping with the director's remarkable ability as a stylistic chameleon. Whereas the latter work is a sober, serious epic, the earlier one is a wild melodrama, a tearjerker like Douglas Sirk might have made if only he'd had a bit more of an eye towards the historical. As well it might be, given that it's essentially Visconti's stab at making a movie of an opera. All the same elements are there: outsized emotions, ludicrous plot twists, and costumes so luscious that if you wanted to, you good just gawk at them the whole time and still have a pretty swell evening.

The relationship between Senso and opera couldn't possibly be made any clearer than it is: the very first shot of the film is of a production of Verdi's Il trovatore at La Fenice. Setting aside the matter of using that highly metaphorical opera to begin a film about the Risorgimento (think of an American Civil War movie opening with a stage production of Uncle Tom's Cabin, and you're in the right ballpark) as better suited to the strengths of an Italian history buff, the production we see is a monumentally lavish affair, though perhaps no more lavish than would have actually been presented in Venice in the 1860s. That being said, we don't get to see too much of it, and rightly so, for as any 19th Century Italian could tell you, the reason for going to the opera is to people-watch and gossip, and we have plenty of both to attend to.

The performance ends with a demonstration protesting the occupying Austrian army, held by a radical group let by Roberto Ussoni (Massimo Girotti). Among those attending the opera is Ussoni's cousin, the Contessa Livia Serpieri (Alida Valli, delectable as always) and her husband (Heinz Moog), a collaborator with the Austrians, here embodied by the wicked Lieutenant Franz Mahler (American actor Farley Granger, early in the European phase of his career). That information all gets doled out to us in bits and pieces, nestled in with a great deal of whispered gossip, and the whole process is shot by Visconti in a tremendously exciting series of quick-moving tracking shots. The director's use of camera movement is always quite exemplary, from the stately tracks that emphasise physical geometry in The Leopard to the tensely-composed static shots that make up most of Death in Venice. But I don't believe that I have yet seen a film of his with such a freewheeling camera as we see in Senso, especially in these opening minutes; the way it races from place to place is a perfect match for the breathless chatter and confusion that it documents in this first scene.

Naturally, there comes to be a plot, and it's a twisty thing: the patriotic Livia, offended by her husband's mewling complacency, finds herself falling in love with a more forceful example of manhood, and it just so happens to be Mahler (which, I suppose, might just be a metaphor in itself). As far as the story goes, that's really all you need: for most of the film's two hours, the contessa and Mahler tryst in her giant home, or she spends her time trying to figure out how to dump her crappy spouse and prolong her country's occupation long enough to make a new home with her Austrian paramour, all while steadfastly ignoring the increasingly obvious signs that he's planning on dicking her over. The delight (as is usually the case in opera) isn't in seeing what happens, but enjoying all the moments along the way.

And, as is usually the case in opera, the chief of all delights is the performance by the woman in the center of it all. Valli is hardly a household name in the United States, known (if at all) primarily for playing the femme fatale in Carol Reed's The Third Man. Which, make no mistake, is a great thing to know her for, typifying what makes her so irresistible in so many things: she's one of the great exotic Europeans who postively ooze sex and mystery just by standing there, irrespective of quibbly little things like "acting ability" (think Claudia Cardinale, or more recently, Asia Argento). Frankly, I don't know that Valli is a good or bad actress per se, but I do know that she is magnetic - if she is onscreen, you are watching her. That's a far more important thing than something so pedestrian as acting. I've personally never seen her in a role of such large size as Livia, nor one that plays so well to her strengths; and the results are incandesent. Senso triumphs on the strength of its leading lady's presence, a glamorous and passionate eye for the whole messy hurricane of betrayal and lust to whirl around.

The rest of the film's pleasures are similarly earthy, rather than esoteric. Like The Leopard after it, Senso looks simply ravishing, not just in the contessa's rich gowns that swirl around like a dancer's veils, but also the set design, focusing on the gilt and detail of the nobility, with just a touch of decay around the edges to remind us of how depraved and corrupt all of it is. Meanwhile, Visconti's camera, as wielded by cinematographer G.R. Aldo in his last film after a career including stints with De Sica and Welles, captures it all with a flair for the dramatic in composition and in movement, all in some of the thickest Technicolor I've ever seen outside of a Hollywood studio production.

For those who require such things, there's a healthy dose of Importance to all of this, most of it to do with the film's historic-political elements, but my needs at the moment I saw it were well-served by the sensual marvels on display. There's precious damn little to the film that's subtle, but remember: opera. Subtlety matter less than being bowled over in lusciousness sometimes, and you'd have to go very far to find a more luscious movie than this one.