The scientist and the demon

Despite the modern reputation that Hammer enjoys as the home for horror in the United Kingdom, the company spent its first two decades of life as just a random British B-picture house, producing mostly forgotten adventure films. That started to change in 1955 with The Quatermass Xperiment the first in what would ultimately prove to be a trilogy of horror/sci-fi pictures based on a highly successful BBC serial. Quatermass was Hammer's biggest hit ever - largely because it was their first film to make a splash in the United States - and the company quickly began looking for the next big horror title they could exploit. They found it in The Curse of Frankenstein, an adaptation of Mary Shelley's Gothic horror novel that was Hammer's first color feature, and a watershed moment in the history of onscreen representation of sex and gore - basically, the studio figured out exactly where the British censor boards would freak out, and pushed juuuust slightly past that point, and rode the subsequent wave of controversy all the way to majestic box office returns. This being 1957, what counted as "controversial" looks altogether quaint, but it was a Big Fucking Deal back in the day, and Hammer immediately found itself on the vanguard of edgy adult entertainment.

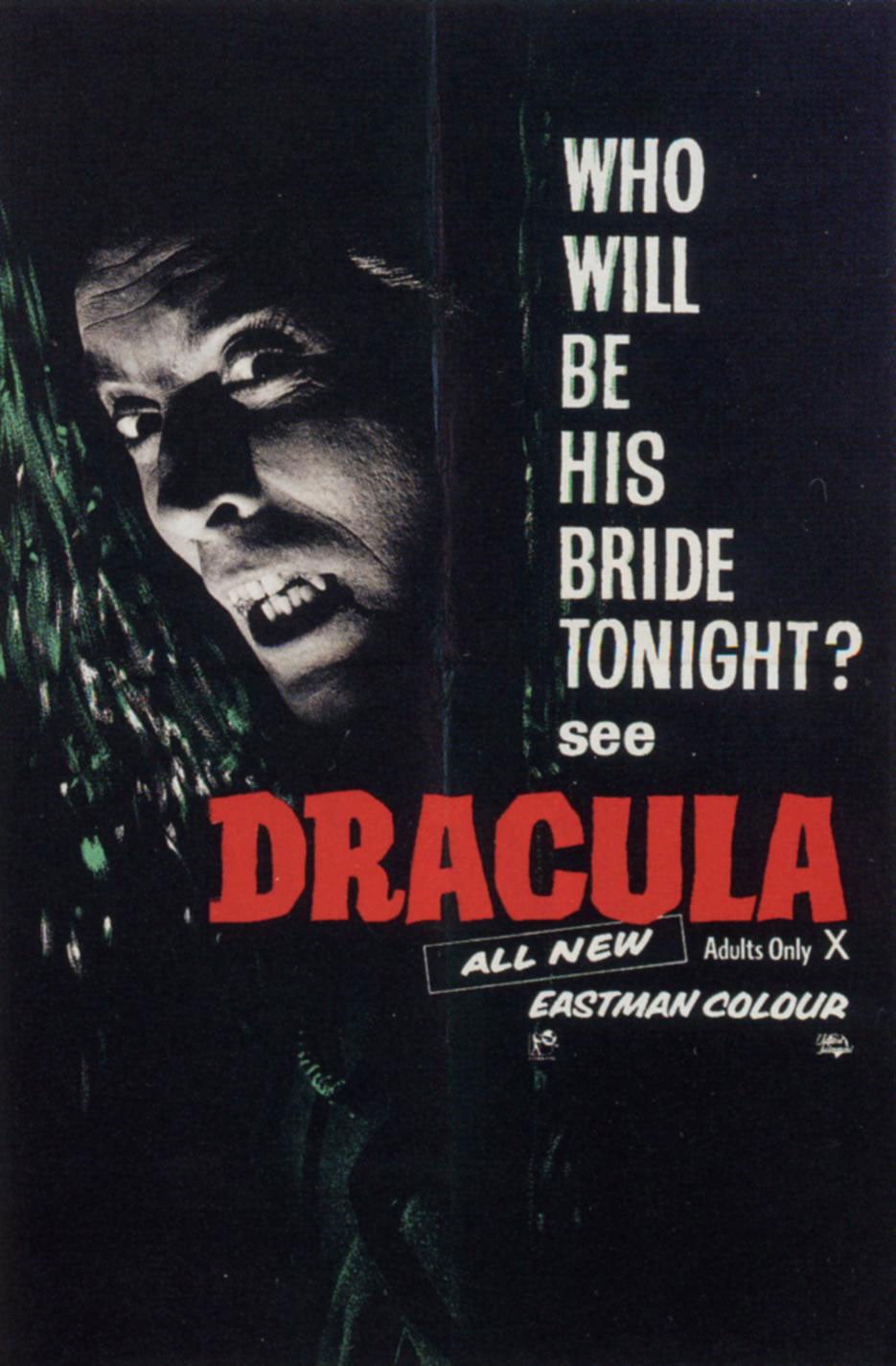

The international success of The Curse of Frankenstein led to a sequel the next year, but in the meanwhile, the Hammer execs found themselves confronting the question: having successfully updated one iconic Universal monster to the world of Technicolor and plentiful blood, where else could they turn? The answer was obvious; and just a couple of months before the first of six Frankenstein sequels hit theaters, Hammer released Dracula (retitled Horror of Dracula in the US, to avoid confusion with the Universal picture).

Based so loosely on Bram Stoker's novel that it performed the seemingly impossible task of making Tod Browning's classic look positively faithful, Hammer's Dracula was nevertheless a smash hit. And why not? It was in many ways a retread of the beloved Curse of Frankenstein, with the same director (the great Terence Fisher), screenwriter (the just as great Jimmy Sangster), and the same two actors as hero and villain from the earlier film: as Dr. Van Helsing, vampire hunter, Hammer's only real star, Peter Cushing, and as Dracula, in the role that turned him from Hammer contract player/"that guy who played Frankenstein's monster" into one of the greatest horror icons in cinema history, the immortal Christopher Lee.

Most people nowadays haven't read Stoker's epistolary novel; I'm not certain that it's a real shame that this is the case (though I personally love it, it takes a truly dedicated student of the Victorian Age to see it as anything but a clumsy potboiler). At any rate, the story in a nutshell: lawyer Jonathan Harker travels to the Transylvanian castle of Count Dracula to advise him on a real estate deal, but learns rather soon that the count is an undead bloodsucking demon. Harker barely escapes, shortly before Dracula travels by boat to England, where he menaces the young lady Lucy Westenra, the dear friend of Harker's fiancée Mina Murray. Lucy at this time has three suitors: Dr. Seward, the owner of an asylum (where a crazed bug-eater named Renfield, later discovered to be in Dracula's thrall, is imprisoned), the Texan Quincey Morris, and Arthur Holmwood, an aristocrat. It doesn't really matter who she chooses, however; by the time she is introduced she is suffering from a wasting disease of unknown origin, spurring Seward to call in his colleague Dr. Abraham Van Helsing to help fight it. Van Helsing realises almost instantly that Lucy is being drained nightly by a vampire; he fails to share this information soon enough to save her life, but when Mina starts to develop the same symptoms, he gathers the three suitors and Harker into a vampire-fighting team.

If that doesn't look very familiar from the movies (there's a Texan in the story?) it's probably because there hasn't yet been a completely satisfying adaptation of a book that's already exorbitantly cinematic. Life is strange like that, sometimes. At any rate, Hammer's Dracula, though a great film on its own merits, is possibly the worst adaptation of the book ever: it opens with Jonathan Harker (John Van Eyssen) arriving at Castle Dracula to maintain the count's library, but we learn through his diary that he's actually there on orders from Van Helsing - the world's greatest vampire expert - to stake the count. Unfortunately for Harker, his mission is discovered fairly soon after he is seduced by Dracula's bride (Valerie Gaunt), a beautiful woman prone to showing outrageous amounts of cleavage, almost like she was trying to subvert cinematic moral codes. Harker ends up vampirised, though not until after he stakes the vampire woman in a remarkably explicit (for 1958) moment, and it falls to Van Helsing to come to the Romanian town of Klausenberg to find and stake his old friend himself.

Not before Dracula has escaped to Karlstadt, Germany, where Harker's fiancée Lucy Holmwood (Carol Marsh) lives with her brother Arthur (Michael Gough) and his wife Mina (Melissa Stribling). See, Dracula found Lucy's photograph among Harker's belongings, and he has already selected her to be his next victim. Van Helsing arrives after Lucy is already quite sick, being fruitlessly treated by Dr. Seward (Charles Lloyd Pack), and though the Holmwoods are doubtful, they trust the vampire's admonition that closing the windows and surrounding Lucy with garlic flowers is the only way to save her. Lucy doesn't take kindly to this, and she has the housekeeper Gerda (Olga Dickie) clear out the room, and the next morning she's found dead. Van Helsing's vampire hunting efforts kick into high gear as soon as Mina starts to suffer from the same anemia-like disease that killed Lucy, and he's joined by Arthur Holmwood just as soon as that conservative man is confronted with his undead sister tormenting Gerda's daughter Tania (Janina Faye). The only question is, where is Dracula hiding, that he can sneak in and out of the house without anybody seeing?

Not very like the book, is it?

Beyond any shadow of a doubt, the first thing that a modern viewer (and probably a 1958 viewer, for that matter) will pay attention to is Christopher Lee's performance as the titular vampire. There is an extremely good reason for this; despite having something like eleven minutes of time on-screen, and thirteen lines of dialogue that all feature in his first scene with Harker, Lee gives a flat-out definitive performance of a vampire that I daresay stomps Bela Lugosi's much more iconic, but unarguably hambone portrayal of the count right into the ground. The only vampire I can think of that trumps Lee's Dracula is Max Schreck's Count Orlok in Murnau's illegal Dracula adaptation from 1922, Nosferatu, and it cannot be a coincidence that both performances share a similar approach to vampirism that's mostly ignored in the greater bulk of popular culture. Lee's Dracula, like Schreck's is not a cultured nobleman, and he's not a tortured lover, and he's really not very charismatic at all. He's an animal, a beast that preys on human beings like cattle, snarling and hissing with blood-red eyes (courtesy of contact lenses that Lee bitched about, like he bitched about everything Dracula-related; but that is a story for next time). It's unabashedly unnerving, even if it's not quite "scary", 50 years later; and how many vampire movies can even make that modest claim?

The thing about Lee is, he's not much of a presence in the film, even at it's tidy 82-minute runtime. So the heavy lifting required to make Dracula memorable is mostly done elsewhere, mostly in the figure of Cushing's Van Helsing. It's a crime that Peter Cushing is primarily, even exclusively, known to a full three generations of filmgoers as Grand Moff Tarkin in Star Wars; back in the day, especially in Britain, he was an absolute superstar in horror films, and with plenty of justification. No matter how silly and overwrought his surroundings, Cushing never let it show: his absolute professionalism is unmistakable at every moment of every performance I've ever seen him give, and despite his commanding work as Victor Frankenstein, his first attempt at Dr. Van Helsing is quite possibly the highlight of his five-decade career. In Hammer's iteration, Van Helsing is a consummate man of science, treating vampirism as a disease to be fought using experimentation and observation. It's thanks entirely to Cushing's level-headed performance that we can believe and fully engage with the sometimes absurd bends in the plot, and if Lee is responsible for making Dracula a classic, Cushing is the reason that it achieves the much harder victory of being an objectively good film.

But having praised those two actors, I could never skip over Terence Fisher, one of the unsung masters of genre filmmaking in Britan or anywhere else (sure, you've heard of Tod Browning and James Whale, maybe even Jack Arnold, to say nothing of Lang, Murnau or Mamoulian; Fisher is the equal to any of them, at least as far as horror is concerned). Fisher, as much as any single person, is the reason that Hammer became known for the remarkable quality of its Gothic horror. Now, we can argue whether Gothic horror is quite as exciting as the stylistic magnificence of German Expressionism, and stylistically, the Hammer Dracula simply can't compete with Nosferatu or Vampyr (or even Universal's Dracula, which is otherwise an exemplar of everything wrong with early sound filmmaking) for the title of "most visually exceptional vampire movie". We'll take that as given. Still, the Hammer Gothic style, at is best, is essentially without peer, and it was never better than in Fisher's hands. Despite a tendency towards being overlit, Dracula is a visual feast of rich production design, shot to its fullest effect in a series of unassuming but inevitably correct camera angles (which tend to be just slightly wider than you'd think, and so we're constantly aware of the space of the film), and a nearly breakneck pace that allows not a single moment of flabby excess.

As long as I've got this marvelous love-in happening, let's wrap it up with the final member of the Hammer horror dream team: Jimmy Sangster. Responsible for basically all of Hammer's best scripts, Sangster's work in Dracula isn't quite as good as his screenplay for The Curse of Frankenstein; it's at least somewhat of a liability that Dracula is offscreen so much, and that when he appears at the end he's dispatched so quickly, and Holmwood and Harker are nothing but ciphers, no matter how well-acted. But the core of Dracula is pure genius; to the best of my knowledge, it's the first example anywhere of vampirism as a scientific problem, and as a result the story's Victorian setting has never been exploited quite the same way. In Sangster's hands, Van Helsing reaches his apotheosis as a character, devoted to the scientific method and as intelligent and competent as he could ever be. He's the great vampire hunter, because he represents the forces of modernity and the Enlightenment marching against superstition and fear, and if the nugget for that metaphor was already present in Stoker's novel, it never came close to being so beautifully expressed as it was in this film, as opposed to Van Helsing's traditional representation as a crackpot mystic with a proclivity towards leg-humping.

There will never be a greater vampire film than Nosferatu or Vampyr, not ever. But Hammer's Dracula puts up a strong fight to come in at third place. The film has it all, really: a truly threatening vampire (as played, if not as written), a nearly perfect hero, grand style, and the good sense to present the vampire as a monster, not a tragic Goth hero. Catch me in a generous mood, and I might call it the single best horror film made between the end of the 1930s and the beginning of the 1970s. There's a reason why classic films become classics, and despite losing some of its visceral impact thanks to the very same lightening of censorship that it helped to encourage, Dracula thrills the blood like very few movies in the genre before or since.

Reviews in this series

Dracula (Fisher, 1958)

The Brides of Dracula (Fisher, 1960)

Dracula: Prince of Darkness (Fisher, 1966)

Dracula Has Risen from the Grave (Francis, 1968)

Taste the Blood of Dracula (Sasdy, 1970)

Scars of Dracula (Baker, 1970)

Dracula A.D. 1972 (Gibson, 1972)

The Satanic Rites of Dracula (Gibson, 1974)

The Legend of the 7 Golden Vampires (Baker, 1974)

The international success of The Curse of Frankenstein led to a sequel the next year, but in the meanwhile, the Hammer execs found themselves confronting the question: having successfully updated one iconic Universal monster to the world of Technicolor and plentiful blood, where else could they turn? The answer was obvious; and just a couple of months before the first of six Frankenstein sequels hit theaters, Hammer released Dracula (retitled Horror of Dracula in the US, to avoid confusion with the Universal picture).

Based so loosely on Bram Stoker's novel that it performed the seemingly impossible task of making Tod Browning's classic look positively faithful, Hammer's Dracula was nevertheless a smash hit. And why not? It was in many ways a retread of the beloved Curse of Frankenstein, with the same director (the great Terence Fisher), screenwriter (the just as great Jimmy Sangster), and the same two actors as hero and villain from the earlier film: as Dr. Van Helsing, vampire hunter, Hammer's only real star, Peter Cushing, and as Dracula, in the role that turned him from Hammer contract player/"that guy who played Frankenstein's monster" into one of the greatest horror icons in cinema history, the immortal Christopher Lee.

Most people nowadays haven't read Stoker's epistolary novel; I'm not certain that it's a real shame that this is the case (though I personally love it, it takes a truly dedicated student of the Victorian Age to see it as anything but a clumsy potboiler). At any rate, the story in a nutshell: lawyer Jonathan Harker travels to the Transylvanian castle of Count Dracula to advise him on a real estate deal, but learns rather soon that the count is an undead bloodsucking demon. Harker barely escapes, shortly before Dracula travels by boat to England, where he menaces the young lady Lucy Westenra, the dear friend of Harker's fiancée Mina Murray. Lucy at this time has three suitors: Dr. Seward, the owner of an asylum (where a crazed bug-eater named Renfield, later discovered to be in Dracula's thrall, is imprisoned), the Texan Quincey Morris, and Arthur Holmwood, an aristocrat. It doesn't really matter who she chooses, however; by the time she is introduced she is suffering from a wasting disease of unknown origin, spurring Seward to call in his colleague Dr. Abraham Van Helsing to help fight it. Van Helsing realises almost instantly that Lucy is being drained nightly by a vampire; he fails to share this information soon enough to save her life, but when Mina starts to develop the same symptoms, he gathers the three suitors and Harker into a vampire-fighting team.

If that doesn't look very familiar from the movies (there's a Texan in the story?) it's probably because there hasn't yet been a completely satisfying adaptation of a book that's already exorbitantly cinematic. Life is strange like that, sometimes. At any rate, Hammer's Dracula, though a great film on its own merits, is possibly the worst adaptation of the book ever: it opens with Jonathan Harker (John Van Eyssen) arriving at Castle Dracula to maintain the count's library, but we learn through his diary that he's actually there on orders from Van Helsing - the world's greatest vampire expert - to stake the count. Unfortunately for Harker, his mission is discovered fairly soon after he is seduced by Dracula's bride (Valerie Gaunt), a beautiful woman prone to showing outrageous amounts of cleavage, almost like she was trying to subvert cinematic moral codes. Harker ends up vampirised, though not until after he stakes the vampire woman in a remarkably explicit (for 1958) moment, and it falls to Van Helsing to come to the Romanian town of Klausenberg to find and stake his old friend himself.

Not before Dracula has escaped to Karlstadt, Germany, where Harker's fiancée Lucy Holmwood (Carol Marsh) lives with her brother Arthur (Michael Gough) and his wife Mina (Melissa Stribling). See, Dracula found Lucy's photograph among Harker's belongings, and he has already selected her to be his next victim. Van Helsing arrives after Lucy is already quite sick, being fruitlessly treated by Dr. Seward (Charles Lloyd Pack), and though the Holmwoods are doubtful, they trust the vampire's admonition that closing the windows and surrounding Lucy with garlic flowers is the only way to save her. Lucy doesn't take kindly to this, and she has the housekeeper Gerda (Olga Dickie) clear out the room, and the next morning she's found dead. Van Helsing's vampire hunting efforts kick into high gear as soon as Mina starts to suffer from the same anemia-like disease that killed Lucy, and he's joined by Arthur Holmwood just as soon as that conservative man is confronted with his undead sister tormenting Gerda's daughter Tania (Janina Faye). The only question is, where is Dracula hiding, that he can sneak in and out of the house without anybody seeing?

Not very like the book, is it?

Beyond any shadow of a doubt, the first thing that a modern viewer (and probably a 1958 viewer, for that matter) will pay attention to is Christopher Lee's performance as the titular vampire. There is an extremely good reason for this; despite having something like eleven minutes of time on-screen, and thirteen lines of dialogue that all feature in his first scene with Harker, Lee gives a flat-out definitive performance of a vampire that I daresay stomps Bela Lugosi's much more iconic, but unarguably hambone portrayal of the count right into the ground. The only vampire I can think of that trumps Lee's Dracula is Max Schreck's Count Orlok in Murnau's illegal Dracula adaptation from 1922, Nosferatu, and it cannot be a coincidence that both performances share a similar approach to vampirism that's mostly ignored in the greater bulk of popular culture. Lee's Dracula, like Schreck's is not a cultured nobleman, and he's not a tortured lover, and he's really not very charismatic at all. He's an animal, a beast that preys on human beings like cattle, snarling and hissing with blood-red eyes (courtesy of contact lenses that Lee bitched about, like he bitched about everything Dracula-related; but that is a story for next time). It's unabashedly unnerving, even if it's not quite "scary", 50 years later; and how many vampire movies can even make that modest claim?

The thing about Lee is, he's not much of a presence in the film, even at it's tidy 82-minute runtime. So the heavy lifting required to make Dracula memorable is mostly done elsewhere, mostly in the figure of Cushing's Van Helsing. It's a crime that Peter Cushing is primarily, even exclusively, known to a full three generations of filmgoers as Grand Moff Tarkin in Star Wars; back in the day, especially in Britain, he was an absolute superstar in horror films, and with plenty of justification. No matter how silly and overwrought his surroundings, Cushing never let it show: his absolute professionalism is unmistakable at every moment of every performance I've ever seen him give, and despite his commanding work as Victor Frankenstein, his first attempt at Dr. Van Helsing is quite possibly the highlight of his five-decade career. In Hammer's iteration, Van Helsing is a consummate man of science, treating vampirism as a disease to be fought using experimentation and observation. It's thanks entirely to Cushing's level-headed performance that we can believe and fully engage with the sometimes absurd bends in the plot, and if Lee is responsible for making Dracula a classic, Cushing is the reason that it achieves the much harder victory of being an objectively good film.

But having praised those two actors, I could never skip over Terence Fisher, one of the unsung masters of genre filmmaking in Britan or anywhere else (sure, you've heard of Tod Browning and James Whale, maybe even Jack Arnold, to say nothing of Lang, Murnau or Mamoulian; Fisher is the equal to any of them, at least as far as horror is concerned). Fisher, as much as any single person, is the reason that Hammer became known for the remarkable quality of its Gothic horror. Now, we can argue whether Gothic horror is quite as exciting as the stylistic magnificence of German Expressionism, and stylistically, the Hammer Dracula simply can't compete with Nosferatu or Vampyr (or even Universal's Dracula, which is otherwise an exemplar of everything wrong with early sound filmmaking) for the title of "most visually exceptional vampire movie". We'll take that as given. Still, the Hammer Gothic style, at is best, is essentially without peer, and it was never better than in Fisher's hands. Despite a tendency towards being overlit, Dracula is a visual feast of rich production design, shot to its fullest effect in a series of unassuming but inevitably correct camera angles (which tend to be just slightly wider than you'd think, and so we're constantly aware of the space of the film), and a nearly breakneck pace that allows not a single moment of flabby excess.

As long as I've got this marvelous love-in happening, let's wrap it up with the final member of the Hammer horror dream team: Jimmy Sangster. Responsible for basically all of Hammer's best scripts, Sangster's work in Dracula isn't quite as good as his screenplay for The Curse of Frankenstein; it's at least somewhat of a liability that Dracula is offscreen so much, and that when he appears at the end he's dispatched so quickly, and Holmwood and Harker are nothing but ciphers, no matter how well-acted. But the core of Dracula is pure genius; to the best of my knowledge, it's the first example anywhere of vampirism as a scientific problem, and as a result the story's Victorian setting has never been exploited quite the same way. In Sangster's hands, Van Helsing reaches his apotheosis as a character, devoted to the scientific method and as intelligent and competent as he could ever be. He's the great vampire hunter, because he represents the forces of modernity and the Enlightenment marching against superstition and fear, and if the nugget for that metaphor was already present in Stoker's novel, it never came close to being so beautifully expressed as it was in this film, as opposed to Van Helsing's traditional representation as a crackpot mystic with a proclivity towards leg-humping.

There will never be a greater vampire film than Nosferatu or Vampyr, not ever. But Hammer's Dracula puts up a strong fight to come in at third place. The film has it all, really: a truly threatening vampire (as played, if not as written), a nearly perfect hero, grand style, and the good sense to present the vampire as a monster, not a tragic Goth hero. Catch me in a generous mood, and I might call it the single best horror film made between the end of the 1930s and the beginning of the 1970s. There's a reason why classic films become classics, and despite losing some of its visceral impact thanks to the very same lightening of censorship that it helped to encourage, Dracula thrills the blood like very few movies in the genre before or since.

Reviews in this series

Dracula (Fisher, 1958)

The Brides of Dracula (Fisher, 1960)

Dracula: Prince of Darkness (Fisher, 1966)

Dracula Has Risen from the Grave (Francis, 1968)

Taste the Blood of Dracula (Sasdy, 1970)

Scars of Dracula (Baker, 1970)

Dracula A.D. 1972 (Gibson, 1972)

The Satanic Rites of Dracula (Gibson, 1974)

The Legend of the 7 Golden Vampires (Baker, 1974)

Categories: british cinema, hammer films, horror, production design-o-rama, vampires