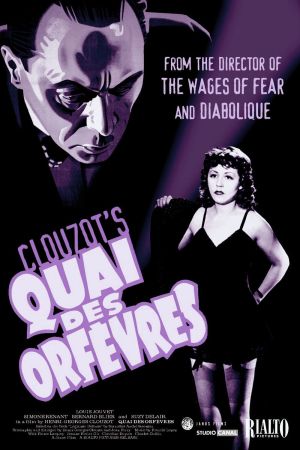

They Shoot Pictures, Don't They? 2008 Edition - #869

Despite being named for the street where Paris's most important police station is located (imagine titling a film Scotland Yard), despite a plot jammed full of intrigue and twists, and despite being written and directed by Henri-Georges Clouzot, a French filmmaker noted for his exceptionally taut movies, Quai des Orfèvres is actually a pretty lousy crime thriller. If not for the reliance on a truly amazing string of coincidences, people in exactly the right place to say exactly the right thing to the cops at just the perfect moment, there would still be one of the most howlingly contrived climaxes imaginable, in which the only piece of information the audience wasn't aware of long before any of the characters turns out to be the key to giving the film its unlikely happy ending. Despite this, Quai des Orfèvres is among the very best French films of the 1940s, and one of the most ridiculously enjoyable films of the director's career.

About Henri-Georges Clouzot: an unabashed auteur in the years shortly before that term began to gain real currency, he was one of the few examples of a dedicated writer-director in those days (he never once directed a screenplay that he didn't at least co-write). After puttering around for a while in the 1930s French film industry, he made his solo directing debut with The Murderer Lives at #21 and Le Corbeau, a pair of mysteries with a black-hearted comic edge that quickly established Clouzot's reputation for misanthropic social commentary. And that's not the only reputation they gave him: as the films were produced by the Nazi-friendly Continental Films, the nasty-minded tenor of Le Corbeau especially led to that film's tarring as a deliberate piece of anti-French propaganda, and Clouzot was briefly banned from the post-war industry for his alleged collaboration. I don't know from France in the 1940s, but I do know a little something about artists, and while some of them will stand on principle in times of crisis, there are plenty who would make any bargain to keep on working, no matter how much compromise it takes. Besides, Le Corbeau is no more anti-French than it is anti-everyone: hypocrisy knows no nation, not even in wartime.

Still, I expect that sensitivity to those charges explains the most curious quality about Quai des Orfèvres, compared to the rest of Clouzot's output: while Le Corbeau and later masterpieces like The Wages of Fear have left him with a deserved reputation as a take-no-prisoners misanthrope of unlimited bile, Quai des Orfèvres is primarily notable for how very much affection the writer-director makes us feel for virtually every character. Maybe it's just a Christmas miracle (the film's climax occurs at midnight on December 25th, after all), maybe it's Clouzot's privately cynical attempt to prove to the very accommodating French authorities that he could play nice, but Quai des Orfèvres is a masterpiece of humanism, even by the standards of a national cinema unusually disposed to humanism before the '50s and '60s came along.

The film opens with Maurice Martineau (Bernard Blier), a pudgy man with a worried face who looks a full decade older than his 30 years, meeting Jenny Lamour (Suzy Delair), born Marguerite Chauffournier, a sweetly sexy music hall singer who auditions with the song publisher where Maurice works as piano accompanist. One tremendously lovely montage later, Jenny has taken the song "Avec son tra-la-la" to superstardom, or at least the closest to superstardom that the Parisian music hall scene in 1946 could support, and she's married Maurice, living with him in a small apartment above his child friend, the professional photographer Dora Monnier (Simone Renant). Being a fixture at the local music hall isn't good enough for a woman as self-assured as Jenny, though, and she happily uses her feminine charms to seduce a hunchbacked movie producer named Georges Brignon (Charles Dullin), over Maurice's loud objections and Dora's much subtler warnings.

Eventually, a fed-up Maurice confronts Brignon in a restaurant, declaring that he will kill the older man if he ever looks at Jenny again. A couple of days later, he prepares to make good on that promise, learning that his wife has lied to him about visiting her sick grandmother when in fact she has a private meeting at the producer's home; the jealous man heads there with murder on his mind, only to find that somebody already beat him to the punch. "Somebody" turns out to be Jenny herself, who tearily confesses to Dora that she never expected Brignon to actually put the moves on her, which is when she bonked him on the head with a champagne bottle. Without further ado, Dora goes to the dead man's home to clean up the evidence, Maurice starts to worry that he's the obvious suspect for a crime he intended to commit, and the case is handed off to the weary Inspector Antoine (French theater icon Louis Jouvet), of the homicide division at 36 Quai des Orfèvres.

There are two, perhaps even three films locked inside this single body. Obviously, there's a crime drama to be had, a jealous lover melodrama cum Hitchcockian "wrong man" thriller, and Clouzot is a fantastic enough filmmaker to wring the most tension he can out of the scenario. But that's not really what he's interested in, attested to the fact that he wrote the adaptation of Stanislas-André Steerman's Légitime défense from memory, earning the wrath of the novelist for all the details he got wrong. The heart of Quai des Orfèvres lies not in its procedural story (which veers from great to frustrating, depending on the level of contrivance involved in the given scene), but in the "where" and "to whom" of that story. Always a director given to obsessive control of little details, Clouzot's evocation of the down-market music halls of France in December, 1946, provides one of the most fully-realized settings for any crime film in history. Indeed, you could take the crime film out of it entirely and still revel in the loving depiction of the Parisian theatrical community, especially in the first half of the film, packed with short vignettes exploring the backstage and the people running through it, in their neurotic and perfectionist glory. To a certain extent, these details are probably accidental; Clouzot was after all shooting the film in the very real December of 1946, and not likely concerned with what people would think about his film 60 years later, but the niceties of such things like all the people in the film wearing coats even indoors - since the city hadn't yet recovered from the ravages of war - give the film's Paris a tremendously lived-in quality that few movie cities ever really attain.

It's the characters who really make the film, though. It's almost impossible to imagine that the man whose last film was Le Corbeau could find it within himself to write a screenplay in which we basically love every single person who walks across the screen, but the sheer glut of humanising details leaves Quai des Orfèvres as just about the most sensitive police procedural imaginable. Take Antoine: a tired man who doesn't fight crime because he's an impassioned ideologue, but because it's his job, and one that he gets really annoyed with when it takes him away from his precious and rare free time with his motherless son, a mixed-race child from Antoine's unelucidated history in the French colonies. That Antoine loves his son without reservation is clear at every moment that he's spoken about, or onscreen (one of my favorite moments in the film is when the detective learns that his son failed to pass his geometry exam, and muses what to do with the already-wrapped Meccano set that was meant as a congratulatory gift; it'll serve for a Christmas present, mutters Antoine, and Jouvet's expression perfectly captures the look of an indulgent father who knows that his boy will be playing with the toy before more than a couple of nights have passed). Using children as a means to humanise gruff police officers is beyond clichéd, of course, but I'd challenge anyone to tell me when it's been used to such perfection as it is in the final shot of Quai des Orfèvres.

Each of the main characters is similarly rich, similarly full; thus do we understand completely Maurice's jealous rage, even as we can see why Jenny is so frustrated by his unwillingness to let her lead a free life. My favorite characterisation might actually be Dora's, though: we're first introduced to the character hidden behind a puff of cigarette smoke with her name, written on her shirt, the only identifiable feature; it's a great way to meet a woman whose motivations and history will always be a bit cloudy - why does she put herself at such risk for Jenny and Maurice? - until Antoine explains in one line of dialogue near the end that he alone of all the characters in the film understands who she truly is, and he sympathises completely. And once we know, it comes as a shock that it was always written right there on her face - and we sympathise, too.

For a genre as traditionally chilly as the crime thriller to produce a work of such warm humanity is a surprise; double that when we factor in the even chillier director. But it's not because Quai des Orfèvres is unexpected that it's so easy to regard it as a masterpiece; it's because it's a beautifully-made and beautifully-written film about people stuck in a place that won't let them lead anything but a crummy, second-rate life. This is classical French cinema at its very best.

About Henri-Georges Clouzot: an unabashed auteur in the years shortly before that term began to gain real currency, he was one of the few examples of a dedicated writer-director in those days (he never once directed a screenplay that he didn't at least co-write). After puttering around for a while in the 1930s French film industry, he made his solo directing debut with The Murderer Lives at #21 and Le Corbeau, a pair of mysteries with a black-hearted comic edge that quickly established Clouzot's reputation for misanthropic social commentary. And that's not the only reputation they gave him: as the films were produced by the Nazi-friendly Continental Films, the nasty-minded tenor of Le Corbeau especially led to that film's tarring as a deliberate piece of anti-French propaganda, and Clouzot was briefly banned from the post-war industry for his alleged collaboration. I don't know from France in the 1940s, but I do know a little something about artists, and while some of them will stand on principle in times of crisis, there are plenty who would make any bargain to keep on working, no matter how much compromise it takes. Besides, Le Corbeau is no more anti-French than it is anti-everyone: hypocrisy knows no nation, not even in wartime.

Still, I expect that sensitivity to those charges explains the most curious quality about Quai des Orfèvres, compared to the rest of Clouzot's output: while Le Corbeau and later masterpieces like The Wages of Fear have left him with a deserved reputation as a take-no-prisoners misanthrope of unlimited bile, Quai des Orfèvres is primarily notable for how very much affection the writer-director makes us feel for virtually every character. Maybe it's just a Christmas miracle (the film's climax occurs at midnight on December 25th, after all), maybe it's Clouzot's privately cynical attempt to prove to the very accommodating French authorities that he could play nice, but Quai des Orfèvres is a masterpiece of humanism, even by the standards of a national cinema unusually disposed to humanism before the '50s and '60s came along.

The film opens with Maurice Martineau (Bernard Blier), a pudgy man with a worried face who looks a full decade older than his 30 years, meeting Jenny Lamour (Suzy Delair), born Marguerite Chauffournier, a sweetly sexy music hall singer who auditions with the song publisher where Maurice works as piano accompanist. One tremendously lovely montage later, Jenny has taken the song "Avec son tra-la-la" to superstardom, or at least the closest to superstardom that the Parisian music hall scene in 1946 could support, and she's married Maurice, living with him in a small apartment above his child friend, the professional photographer Dora Monnier (Simone Renant). Being a fixture at the local music hall isn't good enough for a woman as self-assured as Jenny, though, and she happily uses her feminine charms to seduce a hunchbacked movie producer named Georges Brignon (Charles Dullin), over Maurice's loud objections and Dora's much subtler warnings.

Eventually, a fed-up Maurice confronts Brignon in a restaurant, declaring that he will kill the older man if he ever looks at Jenny again. A couple of days later, he prepares to make good on that promise, learning that his wife has lied to him about visiting her sick grandmother when in fact she has a private meeting at the producer's home; the jealous man heads there with murder on his mind, only to find that somebody already beat him to the punch. "Somebody" turns out to be Jenny herself, who tearily confesses to Dora that she never expected Brignon to actually put the moves on her, which is when she bonked him on the head with a champagne bottle. Without further ado, Dora goes to the dead man's home to clean up the evidence, Maurice starts to worry that he's the obvious suspect for a crime he intended to commit, and the case is handed off to the weary Inspector Antoine (French theater icon Louis Jouvet), of the homicide division at 36 Quai des Orfèvres.

There are two, perhaps even three films locked inside this single body. Obviously, there's a crime drama to be had, a jealous lover melodrama cum Hitchcockian "wrong man" thriller, and Clouzot is a fantastic enough filmmaker to wring the most tension he can out of the scenario. But that's not really what he's interested in, attested to the fact that he wrote the adaptation of Stanislas-André Steerman's Légitime défense from memory, earning the wrath of the novelist for all the details he got wrong. The heart of Quai des Orfèvres lies not in its procedural story (which veers from great to frustrating, depending on the level of contrivance involved in the given scene), but in the "where" and "to whom" of that story. Always a director given to obsessive control of little details, Clouzot's evocation of the down-market music halls of France in December, 1946, provides one of the most fully-realized settings for any crime film in history. Indeed, you could take the crime film out of it entirely and still revel in the loving depiction of the Parisian theatrical community, especially in the first half of the film, packed with short vignettes exploring the backstage and the people running through it, in their neurotic and perfectionist glory. To a certain extent, these details are probably accidental; Clouzot was after all shooting the film in the very real December of 1946, and not likely concerned with what people would think about his film 60 years later, but the niceties of such things like all the people in the film wearing coats even indoors - since the city hadn't yet recovered from the ravages of war - give the film's Paris a tremendously lived-in quality that few movie cities ever really attain.

It's the characters who really make the film, though. It's almost impossible to imagine that the man whose last film was Le Corbeau could find it within himself to write a screenplay in which we basically love every single person who walks across the screen, but the sheer glut of humanising details leaves Quai des Orfèvres as just about the most sensitive police procedural imaginable. Take Antoine: a tired man who doesn't fight crime because he's an impassioned ideologue, but because it's his job, and one that he gets really annoyed with when it takes him away from his precious and rare free time with his motherless son, a mixed-race child from Antoine's unelucidated history in the French colonies. That Antoine loves his son without reservation is clear at every moment that he's spoken about, or onscreen (one of my favorite moments in the film is when the detective learns that his son failed to pass his geometry exam, and muses what to do with the already-wrapped Meccano set that was meant as a congratulatory gift; it'll serve for a Christmas present, mutters Antoine, and Jouvet's expression perfectly captures the look of an indulgent father who knows that his boy will be playing with the toy before more than a couple of nights have passed). Using children as a means to humanise gruff police officers is beyond clichéd, of course, but I'd challenge anyone to tell me when it's been used to such perfection as it is in the final shot of Quai des Orfèvres.

Each of the main characters is similarly rich, similarly full; thus do we understand completely Maurice's jealous rage, even as we can see why Jenny is so frustrated by his unwillingness to let her lead a free life. My favorite characterisation might actually be Dora's, though: we're first introduced to the character hidden behind a puff of cigarette smoke with her name, written on her shirt, the only identifiable feature; it's a great way to meet a woman whose motivations and history will always be a bit cloudy - why does she put herself at such risk for Jenny and Maurice? - until Antoine explains in one line of dialogue near the end that he alone of all the characters in the film understands who she truly is, and he sympathises completely. And once we know, it comes as a shock that it was always written right there on her face - and we sympathise, too.

For a genre as traditionally chilly as the crime thriller to produce a work of such warm humanity is a surprise; double that when we factor in the even chillier director. But it's not because Quai des Orfèvres is unexpected that it's so easy to regard it as a masterpiece; it's because it's a beautifully-made and beautifully-written film about people stuck in a place that won't let them lead anything but a crummy, second-rate life. This is classical French cinema at its very best.