If he could have known that he was an orphan, perhaps he would have cried the louder

Author's note: I have strong suspicions that I no longer agree with much of any of this review, but I haven't seen the film since it was new in theaters - one of these days I really must revisit it and find out.

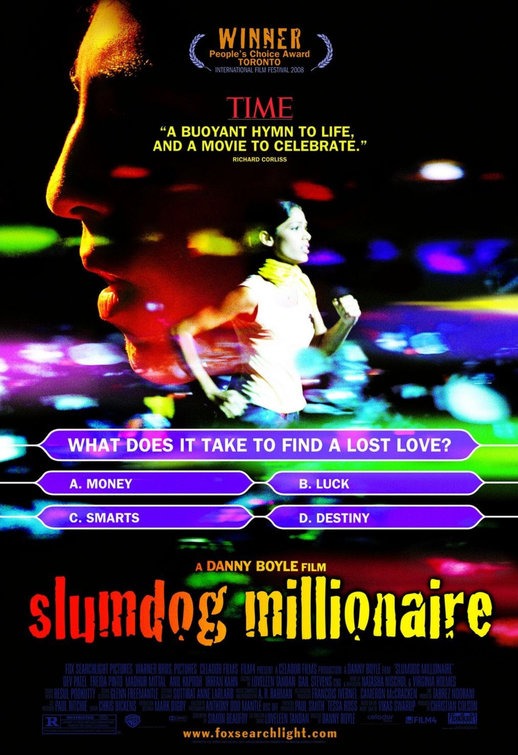

The career of Danny Boyle has gone more places than just about any other modern filmmaker I can think of: from the drug caper Trainspotting to the gory and grim horror experiment 28 Days Later; from the philosophically overburdened adventure film The Beach to the sweet family comedy Millions; from the wimpy Gen-X romcom A Life Less Ordinary to the confounding and atmospheric science fiction drama Sunshine. His newest feature, Slumdog Millionaire, finds him dabbling in yet another valley of the cinematic landscape: it's the biography of a young Indian man with a Citizen Kane-esque narrative hook, and more of the freewheeling style that first made Boyle's reputation than any of his films since Trainspotting, twelve years ago.

The word "slumdog" proves to be a derogatory way of referring to the poor young residents of Mumbai's ample slums, and the particular slumdog of the title is 18-year-old Jamal Malik (Dev Patel), who serves tea at a local call-bank and seems altogether the wrong sort of person to end up one question away from the 20 million rupee grand prize on the Indian version of Who Wants to be a Millionaire, which is exactly the situation he finds himself in as the movie starts up, sitting across from the cheerful host Prem Kumar (Bollywood superstar Anil Kapoor). Cheekily appropriating that show's question format, the film asks us to consider how such a man as this could have ended up in the hot seat: is he cheating, lucky, a genius, or is it destiny? That the question could be asked that way strongly implies the answer, but not everyone is a member of the movie's audience, and that's why Jamal ends up in the hands of a police inspector (Irfan Khan, one of Bollywood's preeminent ambassadors to Western cinema), convinced that the young man is cheating. Some very enhanced interrogation techniques convince the inspector of two things: that Jamal is no cheat, and he's not in the game for money. Thus armed with even more questions, he drifts into a new line of questioning: who is this kid, anyway?

The answer to that question is nested in a narrative framework both simple and ingenious: while the inspector and Jamal watch a tape of that night's Millionaire, the cop frequently stops the tape to ask how on Earth the boy knew the answer. Jamal's response takes the form of a flashback to his childhood, and a horrid, Dickensian childhood it was, too, with a tragically dead mother, a manipulative gang leader, starvation, beatings, and any number of such charming things. The specific nature of these things I would never reveal, for that is the whole point of the movie; but in the main, Jamal's life story is also the story of his relationship with his brother Salim (Madhur Mittal), and his continuing quest to find Latika (Freida Pinto), the young woman he invites in from the rain one evening, and loses track of in the winding course of his grueling slumdog life. Incidentally, all three characters are played at three different ages - childhood, adolescence, and young adulthood - by three different actors, and I wish I'd written down their names while I was watching, because I'm damned if I can find the younger performers' names on the internet, and they're all mostly deserving of praise.

One of the film's curious triumphs is how it manages its tone: though the film is relentlessly bleak, showcasing the agonies of Jamal's life without glitz or whitewash, it's always somehow upbeat and even inspiring. Perhaps this is because we know all along that the long road ends with a chance at a 20 million rupee jackpot that will forever change his fortunes; although it's equally curious that by the end of the film, we're no longer terribly interested in whether or not Jamal wins the game. There are much bigger issues at stake, and while most sources give away Jamal's real goal (including the IMDb plot summary), the film hides that fact for long enough that I choose instead to play along.

It's a strange balancing act, warm and fuzzy without committing the sin of making slum life seem pretty and easy; in fact, it's the same balancing act that Boyle performed so well in Trainspotting, which seems to be the film of his which is most akin to Slumdog Millionaire, if only stylistically. And such style! Shot by the director's frequent recent collaborator Anthony Dod Mantle and edited by the reliable but undistinguished Chris Dickens, the film is one of the great formalist joys of 2008: sliding invisibly from video noise-riddled action sequences in the mud of the slum to shiny offices, cutting frantically or sedately as a function of Jamal's state of mind in that moment, I can't imagine anyone honestly claiming to be bored at any point in the film, and that's even before we get to Boyle's potluck approach to the material: a music montage here, a bit of noir-infused horror there, and we must of course end with a gigantic musical number - it is virtually an Indian film, after all (and that musical number is probably the most delightful and fun ending of any film I've seen this year). He even finds a way to make subtitles exciting for those who think that the idea of a movie shot one-third in Hindi is frightening: color-coded to the speaker, they crop up all over the frame, and their position relative to the action is turned into an active part of the film's visual narrative.

In short, this is almost certainly going to end up the most exhilarating movie of prestige season, even as it is almost entirely taken up with suffering and economic degradation. Is that an amoral combination? Maybe, but it's good to see Boyle goofing around with style again, and never in a way that feels particularly undisciplined. Though it's ultimately a bit too slight and contrived to feel like a timeless artistic masterpiece, it succeeds at everything it sets out to do, and it ends up as one of the few genuinely uplifting movies of the year that doesn't mire itself in calculated naïvete to get there.

The career of Danny Boyle has gone more places than just about any other modern filmmaker I can think of: from the drug caper Trainspotting to the gory and grim horror experiment 28 Days Later; from the philosophically overburdened adventure film The Beach to the sweet family comedy Millions; from the wimpy Gen-X romcom A Life Less Ordinary to the confounding and atmospheric science fiction drama Sunshine. His newest feature, Slumdog Millionaire, finds him dabbling in yet another valley of the cinematic landscape: it's the biography of a young Indian man with a Citizen Kane-esque narrative hook, and more of the freewheeling style that first made Boyle's reputation than any of his films since Trainspotting, twelve years ago.

The word "slumdog" proves to be a derogatory way of referring to the poor young residents of Mumbai's ample slums, and the particular slumdog of the title is 18-year-old Jamal Malik (Dev Patel), who serves tea at a local call-bank and seems altogether the wrong sort of person to end up one question away from the 20 million rupee grand prize on the Indian version of Who Wants to be a Millionaire, which is exactly the situation he finds himself in as the movie starts up, sitting across from the cheerful host Prem Kumar (Bollywood superstar Anil Kapoor). Cheekily appropriating that show's question format, the film asks us to consider how such a man as this could have ended up in the hot seat: is he cheating, lucky, a genius, or is it destiny? That the question could be asked that way strongly implies the answer, but not everyone is a member of the movie's audience, and that's why Jamal ends up in the hands of a police inspector (Irfan Khan, one of Bollywood's preeminent ambassadors to Western cinema), convinced that the young man is cheating. Some very enhanced interrogation techniques convince the inspector of two things: that Jamal is no cheat, and he's not in the game for money. Thus armed with even more questions, he drifts into a new line of questioning: who is this kid, anyway?

The answer to that question is nested in a narrative framework both simple and ingenious: while the inspector and Jamal watch a tape of that night's Millionaire, the cop frequently stops the tape to ask how on Earth the boy knew the answer. Jamal's response takes the form of a flashback to his childhood, and a horrid, Dickensian childhood it was, too, with a tragically dead mother, a manipulative gang leader, starvation, beatings, and any number of such charming things. The specific nature of these things I would never reveal, for that is the whole point of the movie; but in the main, Jamal's life story is also the story of his relationship with his brother Salim (Madhur Mittal), and his continuing quest to find Latika (Freida Pinto), the young woman he invites in from the rain one evening, and loses track of in the winding course of his grueling slumdog life. Incidentally, all three characters are played at three different ages - childhood, adolescence, and young adulthood - by three different actors, and I wish I'd written down their names while I was watching, because I'm damned if I can find the younger performers' names on the internet, and they're all mostly deserving of praise.

One of the film's curious triumphs is how it manages its tone: though the film is relentlessly bleak, showcasing the agonies of Jamal's life without glitz or whitewash, it's always somehow upbeat and even inspiring. Perhaps this is because we know all along that the long road ends with a chance at a 20 million rupee jackpot that will forever change his fortunes; although it's equally curious that by the end of the film, we're no longer terribly interested in whether or not Jamal wins the game. There are much bigger issues at stake, and while most sources give away Jamal's real goal (including the IMDb plot summary), the film hides that fact for long enough that I choose instead to play along.

It's a strange balancing act, warm and fuzzy without committing the sin of making slum life seem pretty and easy; in fact, it's the same balancing act that Boyle performed so well in Trainspotting, which seems to be the film of his which is most akin to Slumdog Millionaire, if only stylistically. And such style! Shot by the director's frequent recent collaborator Anthony Dod Mantle and edited by the reliable but undistinguished Chris Dickens, the film is one of the great formalist joys of 2008: sliding invisibly from video noise-riddled action sequences in the mud of the slum to shiny offices, cutting frantically or sedately as a function of Jamal's state of mind in that moment, I can't imagine anyone honestly claiming to be bored at any point in the film, and that's even before we get to Boyle's potluck approach to the material: a music montage here, a bit of noir-infused horror there, and we must of course end with a gigantic musical number - it is virtually an Indian film, after all (and that musical number is probably the most delightful and fun ending of any film I've seen this year). He even finds a way to make subtitles exciting for those who think that the idea of a movie shot one-third in Hindi is frightening: color-coded to the speaker, they crop up all over the frame, and their position relative to the action is turned into an active part of the film's visual narrative.

In short, this is almost certainly going to end up the most exhilarating movie of prestige season, even as it is almost entirely taken up with suffering and economic degradation. Is that an amoral combination? Maybe, but it's good to see Boyle goofing around with style again, and never in a way that feels particularly undisciplined. Though it's ultimately a bit too slight and contrived to feel like a timeless artistic masterpiece, it succeeds at everything it sets out to do, and it ends up as one of the few genuinely uplifting movies of the year that doesn't mire itself in calculated naïvete to get there.