All in the timing

As mindfucks go, the Spanish micro-budget indie Timecrimes is actually a pretty good lay - it's not easy likely that you'd focus on its biggest problems while you're watching. But the next morning, when you've got a little headache on, and you turn over to see this splotchy mess lying in bed next to you, it's like, "Whoa, what the hell was that all about?"

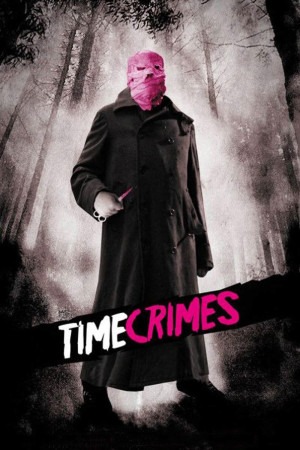

The answer to that question is, "nothing at all, but in the cleverest way possible." Here's the concept: a man named Héctor (Karra Elejalde), who has just moved into a big house in the woods with his wife Clara (Candela Fernández), when he espies strange goings-on in the forest through his binoculars. First, there's a woman (Bárbara Goenaga) standing around doing not much of anything, then she strips off her top, and then she vanishes - and when Héctor goes into the forest to find out what the hell is happening, he spots the woman lying naked and perhaps dead on the ground. He doesn't spot the man with a face all wrapped in pink bandages who comes up behind him and jabs a sharp pair of scissors in his arm.

Thus convinced that a psycho is on the loose, looking to do some carving, Héctor runs to the nearest structure, a laboratory of some sort where he finds a walkie-talkie. The man on the other end (the film's writer-director, Nacho Vigalondo) directs him to a safehouse, where he arrives just moments before the bandaged man can catch him. Quickly ushering Héctor into a kind of floor mounted vault, the man - the scientist, really - pushes a button that lowers the top of the vault, and-

Okay, so I said I'd give you the concept, and then I recapped the first third of the movie. Here's the concept: Héctor goes back in time about six hours, and finds out that the secret behind the woman and the man in the bandage isn't nearly so straightforward as the "psycho killer in the woods" story he'd assumed. Going into it any further than that is to run straight up against spoilers of the very worst kind, given that figuring out exactly what happens and why is precisely the fun of Timecrimes. Let me say only this about it: it plays fair, probably fairer than any other time travel film I can ever name. Ever. Despite a second act that, while you're watching it, feels like an exercise in the most banal time travel plot that can possibly be devised (around minute 50 of 88, I was prepared to write the film off as a feature length illustration of the tautology "things happen because if they don't then nothing would happen"), and a third act that positively gloats in how much it's going to flirt with paradoxes, those saucy things that are always supposed to end the world in time travel movies, Timecrimes pulls it all off. Vigalondo has clearly put a lot of effort into making sure that his story works from every angle, up, down and sideways, without any cheats or logic jumps or obvious fallacies. I mean, besides the big one, about the time machine. Would that all creators of relationship dramedies and biopics would put so much effort into the logical consistency of their screenplays, let alone the teeming masses of shitty, shitty science-fiction writers!

So the problem is what, exactly? Well, once you've watched the film and bathed in the screenplay and marvelled at how remarkably, uniquely sound its construction, what you have left is... dick. Your reward for untangling a perfect puzzle is the knowledge that you just untangled a perfect puzzle. If that's all I want out of life, I can do like four sudokus in the time it takes to watch Timecrimes. The hard sudokus, I mean. The easy ones, man, I could probably do like thirty of those in 90 minutes.

Timecrimes leaves you with nothing: no probing themes, no lasting words of wisdom, not even any exciting production values. You watch it, figure out how it works, and then never have to interact with it ever again. In video games, we'd call this a lack of replay value, and while that's a bigger concern when $60 games are on the line than a $10 movie ticket, I still hold it to be axiomatic that a movie which plants its eggs in your brain and festers there, spawning new insights and revelations every time you look back on it, than to be so ephemeral that you're already done with it when the end credits start to roll.

Vigalondo is clearly a talented filmmaker, to judge from the quick steps he moves the film through, and the perfectly effective slasher-level scares that he trots out during the first third, but mostly he directs without distinction, and without inspiring any of his cast or crew to rise above his example. Okay, the make-up effects are pretty solid. But other than that, we have four actors who merely deliver lands and move through blocking without expending too much obvious effort into figuring out what those lines and blocking indicate (Goenaga is a particular offender in this regard; you'd think a young woman who expects to be raped any moment would have a bit more of an expression on her face). It looks very much like the worst thing that enters your mind when you hear the phrase, "low-budget, shot on video", and if it was not shot on video (full disclosure: I saw it on DVD, not film, such nice distinctions are hard to parse in such circumstances), then everyone involved should be deeply ashamed of themselves.

And thematically, it goes absolutely nowhere. The second act suggests some hints of the ethical quandary of choice vs. free will, but then the third act is cheerfully amoral enough to completely wipe out any slim notion that there's any traction for that idea. Héctor and Clara aren't sufficiently well-defined for any of the screenplay's suggestions that this is partially about the maintenance of marital bliss to take hold in any way but the baldest possible, as hooks to hang a plot development on. It's a little slip of nothing, a good idea badly executed, and nothing more.

The answer to that question is, "nothing at all, but in the cleverest way possible." Here's the concept: a man named Héctor (Karra Elejalde), who has just moved into a big house in the woods with his wife Clara (Candela Fernández), when he espies strange goings-on in the forest through his binoculars. First, there's a woman (Bárbara Goenaga) standing around doing not much of anything, then she strips off her top, and then she vanishes - and when Héctor goes into the forest to find out what the hell is happening, he spots the woman lying naked and perhaps dead on the ground. He doesn't spot the man with a face all wrapped in pink bandages who comes up behind him and jabs a sharp pair of scissors in his arm.

Thus convinced that a psycho is on the loose, looking to do some carving, Héctor runs to the nearest structure, a laboratory of some sort where he finds a walkie-talkie. The man on the other end (the film's writer-director, Nacho Vigalondo) directs him to a safehouse, where he arrives just moments before the bandaged man can catch him. Quickly ushering Héctor into a kind of floor mounted vault, the man - the scientist, really - pushes a button that lowers the top of the vault, and-

Okay, so I said I'd give you the concept, and then I recapped the first third of the movie. Here's the concept: Héctor goes back in time about six hours, and finds out that the secret behind the woman and the man in the bandage isn't nearly so straightforward as the "psycho killer in the woods" story he'd assumed. Going into it any further than that is to run straight up against spoilers of the very worst kind, given that figuring out exactly what happens and why is precisely the fun of Timecrimes. Let me say only this about it: it plays fair, probably fairer than any other time travel film I can ever name. Ever. Despite a second act that, while you're watching it, feels like an exercise in the most banal time travel plot that can possibly be devised (around minute 50 of 88, I was prepared to write the film off as a feature length illustration of the tautology "things happen because if they don't then nothing would happen"), and a third act that positively gloats in how much it's going to flirt with paradoxes, those saucy things that are always supposed to end the world in time travel movies, Timecrimes pulls it all off. Vigalondo has clearly put a lot of effort into making sure that his story works from every angle, up, down and sideways, without any cheats or logic jumps or obvious fallacies. I mean, besides the big one, about the time machine. Would that all creators of relationship dramedies and biopics would put so much effort into the logical consistency of their screenplays, let alone the teeming masses of shitty, shitty science-fiction writers!

So the problem is what, exactly? Well, once you've watched the film and bathed in the screenplay and marvelled at how remarkably, uniquely sound its construction, what you have left is... dick. Your reward for untangling a perfect puzzle is the knowledge that you just untangled a perfect puzzle. If that's all I want out of life, I can do like four sudokus in the time it takes to watch Timecrimes. The hard sudokus, I mean. The easy ones, man, I could probably do like thirty of those in 90 minutes.

Timecrimes leaves you with nothing: no probing themes, no lasting words of wisdom, not even any exciting production values. You watch it, figure out how it works, and then never have to interact with it ever again. In video games, we'd call this a lack of replay value, and while that's a bigger concern when $60 games are on the line than a $10 movie ticket, I still hold it to be axiomatic that a movie which plants its eggs in your brain and festers there, spawning new insights and revelations every time you look back on it, than to be so ephemeral that you're already done with it when the end credits start to roll.

Vigalondo is clearly a talented filmmaker, to judge from the quick steps he moves the film through, and the perfectly effective slasher-level scares that he trots out during the first third, but mostly he directs without distinction, and without inspiring any of his cast or crew to rise above his example. Okay, the make-up effects are pretty solid. But other than that, we have four actors who merely deliver lands and move through blocking without expending too much obvious effort into figuring out what those lines and blocking indicate (Goenaga is a particular offender in this regard; you'd think a young woman who expects to be raped any moment would have a bit more of an expression on her face). It looks very much like the worst thing that enters your mind when you hear the phrase, "low-budget, shot on video", and if it was not shot on video (full disclosure: I saw it on DVD, not film, such nice distinctions are hard to parse in such circumstances), then everyone involved should be deeply ashamed of themselves.

And thematically, it goes absolutely nowhere. The second act suggests some hints of the ethical quandary of choice vs. free will, but then the third act is cheerfully amoral enough to completely wipe out any slim notion that there's any traction for that idea. Héctor and Clara aren't sufficiently well-defined for any of the screenplay's suggestions that this is partially about the maintenance of marital bliss to take hold in any way but the baldest possible, as hooks to hang a plot development on. It's a little slip of nothing, a good idea badly executed, and nothing more.