The eyes of a child

2009 is just barely a month old, but I'm already prepared to call it a better year for movies than 2008. After only 37 days, we've been gifted with the year's first masterpiece; at the very least, it's much superior to all five films currently jockeying for the 2008 Best Picture Oscar.

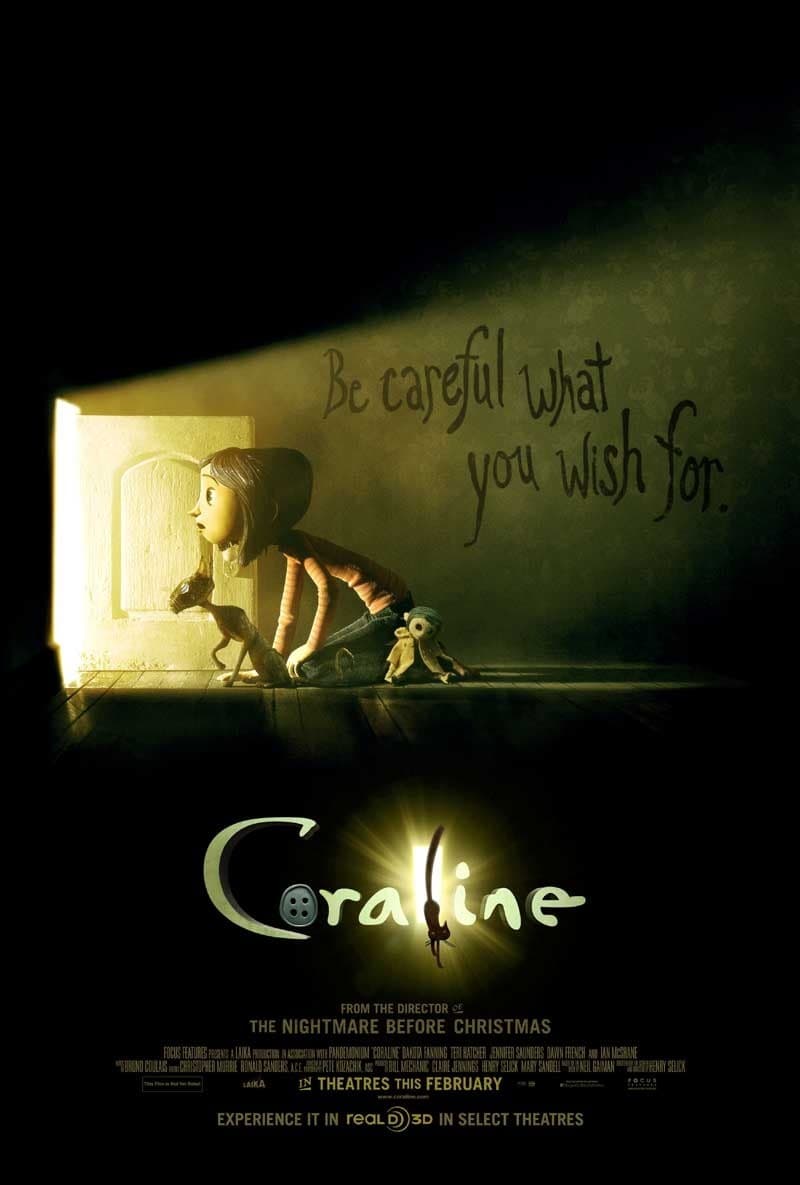

The film is the stop-motion animated Coraline, adapted by writer-director Henry Selick from a marvelous 2002 children's book by Neil Gaiman. It is a straightforward, elementally simple fairy tale: a young girl named Coraline (voiced by Dakota Fanning) moves far away from everything comfortable and familiar because of her emotionally distant parents (Teri Hatcher and John Hodgman), and as she explores the rickety old house where she now lives, she discovers a doorway to another world, where everything is much happier and more colorful, and where an alternate set of parents, identical to the ones she left behind except for having black buttons in place of their eyes, dote on her and give her everything she wants. Eventually, Coraline finds that life in the other house hides a dark secret, and that her endlessly loving Other Mother is really the Beldam (a typically Gaiman contraction of "belle dame sans merci"), who preys on the life force of lonely children.

In its original form, the story was one of the most characteristic things Gaiman ever wrote, an update of ancient storytelling formulas to a modern setting, that never sacrifices the essential timelessness of the material. It's therefore greatly to Selick's credit that his adaptation never feels beholden to Gaiman's novella, that it thrives as a film entirely on its own merits. In some ways, the film is even an improvement on the book; if my memory serves (I haven't read Coraline since it was new, seven years ago), Gaiman only presented Coraline making one trip to the other world before she figures out that something dark is happening, where Selick delays that revelation to her third trip; three being a traditionally important number for magical happenings in fairy tales. In some other ways, the movie is a bit retrograde, such as the addition of a young boy named Wybie (Robert Bailey, Jr.) to help Coraline at the end, apparently a sop to the received wisdom that male children won't respond to stories with female protagonists. But all of that is mostly irrelevant: Coraline-the-movie is a great work unto itself, largely because of how perfectly Selick translates the story into cinematic terms.

The director's most famous work is The Nightmare Before Christmas, usually associated with Tim Burton even though that man had very little to do with the film itself; I hope and expect that Coraline will serve to remind us all of Selick's very important contributions to that project, particularly given that most of what made Nightmare a great film is present to an even greater degree in the newer project. There's the simple but very real pleasure of simply watching great - no, better than great - stop-motion animation, arguably the most labor-intensive form of filmmaking in existence. Between these two films and the mid-'90s adaptation of James and the Giant Peach, Selick has firmly established himself as an absolutely brilliant director of stop-motion, having assembled a team of animators strong enough to make even the groundbreaking solo work of Ray Harryhausen seem decent at best. Coraline is almost without question the most technically accomplished stop-motion in cinema history, and the extraordinary touchability of the exquisite animation puppets and the sets is all the proof I need that there are some things that CGI simply cannot do. No-one has yet made a computer-animated cartoon with such tactility as we see on display here; there is not one moment where Coraline's world does not feel entirely real, for the simple fact that it is real, and this gives the film a deep appeal that even the best CG, such as Pixar's Ratatouille and WALL·E, altogether lack.

This isn't incidental, nor purely for the animation junkies in the audience; since the film's story hinges entirely on Coraline being quickly seduced by the marvels she finds in the world behind the wall, it makes the fantasy that much more effective if we in the audience are seduced just as quickly. Selick and his animators achieve this, both because of the physical quality of their work and the imaginative spectacles they create. Nightmare already proved that Selick is a wonderful fantasist, but it's got nothing on even the middling parts of Coraline, which presents a created world that can stand alongside the finest ever put to film. If I gush, then let me gush, but I find it hard to watch the movie and not conclude that Selick is one of the greatest visionaries in contemporary cinema; every character and location in Coraline is a revelation.

And if all this weren't enough to set the film head and shoulders above any other family fantasy in recent memory, the overwhelming sense of creepiness would be. It's an easy thing for grown-ups to forget, but kids love scary stuff, especially when everything turns out fine in the end. Selick surely knows from creepy, and Coraline far outdoes his previous work in providing unmitigated nightmare fuel, even from an adult perspective: the climax, involving a skeletal spider woman in a shocking high-contrast web is one of the most genuinely unnerving things I've seen in a theater this decade. But it's not all grand statements of children's horror that make the film unsettling and creepy; one of the scenes that freaked me out the most consists of nothing but happy little mice dancing around, in a lower frame-rate than anything else has been animated in the whole movie. The jerky result is an effective early sign that something is wrong in this happy fantasy world.

Having said all that, there's one last thing that gives the film a final push into outright perfection. Coraline is the film I've been awaiting for a long time: it is a 3-D movie in which the dimensional effects aren't just a gimmick, but a vital component of the whole thing. For all that we've been told over and over again that the appeal of 3-D is the way it adds realistic depth to a film, I find it wonderfully ironic that its first truly artistic use should be so blatantly unrealistic. Without getting into the technicals of the whole thing (they're amazing, though), Coraline has two very different depths: in the "real-world" scenes, everything is much flatter than it is in the "other world" scenes, and this difference, though hardly subtle, is absorbed almost subliminally. The point, of course, is that the other world is a magical, fantastic place, much more spectacular than drab reality; so why not depict it using the most spectacular gimmick available to the modern filmmaker? I'm simplifying mightily; the key here is that Coraline is the first 3-D film I've ever seen that does not seem to exist largely as a distributor for cheap trichttps://www.alternateending.com/2009/08/1939-a-whiz-of-a-wiz.htmlkery. It is the film that proves Jeffrey Katzenberg and James Cameron right, that 3-D is a useful storytelling tool; it is the new medium's À nous la liberté (the first film to fully exploit sound), its The Wizard of Oz (color), its Yojimbo (anamorphic widescreen).

For this reason, I find myself completely unable to recommend or even think about the film in anything but its intended 3-D format. Trying to think of Coraline flat is like trying to think of Gone with the Wind in black-and-white, or a silent Meet Me in St. Louis. The story and tremendous craftsmanship are all the same, but something is lost; something that makes this film seem like one of the great cinematic revolutions of my lifetime. By all means, there's enough to the film without 3-D to make it a tremendous fantasy, and one of the best films I've seen in months; but if you have the opportunity to see it in its intended glory, that makes it absolutely essential viewing.

The film is the stop-motion animated Coraline, adapted by writer-director Henry Selick from a marvelous 2002 children's book by Neil Gaiman. It is a straightforward, elementally simple fairy tale: a young girl named Coraline (voiced by Dakota Fanning) moves far away from everything comfortable and familiar because of her emotionally distant parents (Teri Hatcher and John Hodgman), and as she explores the rickety old house where she now lives, she discovers a doorway to another world, where everything is much happier and more colorful, and where an alternate set of parents, identical to the ones she left behind except for having black buttons in place of their eyes, dote on her and give her everything she wants. Eventually, Coraline finds that life in the other house hides a dark secret, and that her endlessly loving Other Mother is really the Beldam (a typically Gaiman contraction of "belle dame sans merci"), who preys on the life force of lonely children.

In its original form, the story was one of the most characteristic things Gaiman ever wrote, an update of ancient storytelling formulas to a modern setting, that never sacrifices the essential timelessness of the material. It's therefore greatly to Selick's credit that his adaptation never feels beholden to Gaiman's novella, that it thrives as a film entirely on its own merits. In some ways, the film is even an improvement on the book; if my memory serves (I haven't read Coraline since it was new, seven years ago), Gaiman only presented Coraline making one trip to the other world before she figures out that something dark is happening, where Selick delays that revelation to her third trip; three being a traditionally important number for magical happenings in fairy tales. In some other ways, the movie is a bit retrograde, such as the addition of a young boy named Wybie (Robert Bailey, Jr.) to help Coraline at the end, apparently a sop to the received wisdom that male children won't respond to stories with female protagonists. But all of that is mostly irrelevant: Coraline-the-movie is a great work unto itself, largely because of how perfectly Selick translates the story into cinematic terms.

The director's most famous work is The Nightmare Before Christmas, usually associated with Tim Burton even though that man had very little to do with the film itself; I hope and expect that Coraline will serve to remind us all of Selick's very important contributions to that project, particularly given that most of what made Nightmare a great film is present to an even greater degree in the newer project. There's the simple but very real pleasure of simply watching great - no, better than great - stop-motion animation, arguably the most labor-intensive form of filmmaking in existence. Between these two films and the mid-'90s adaptation of James and the Giant Peach, Selick has firmly established himself as an absolutely brilliant director of stop-motion, having assembled a team of animators strong enough to make even the groundbreaking solo work of Ray Harryhausen seem decent at best. Coraline is almost without question the most technically accomplished stop-motion in cinema history, and the extraordinary touchability of the exquisite animation puppets and the sets is all the proof I need that there are some things that CGI simply cannot do. No-one has yet made a computer-animated cartoon with such tactility as we see on display here; there is not one moment where Coraline's world does not feel entirely real, for the simple fact that it is real, and this gives the film a deep appeal that even the best CG, such as Pixar's Ratatouille and WALL·E, altogether lack.

This isn't incidental, nor purely for the animation junkies in the audience; since the film's story hinges entirely on Coraline being quickly seduced by the marvels she finds in the world behind the wall, it makes the fantasy that much more effective if we in the audience are seduced just as quickly. Selick and his animators achieve this, both because of the physical quality of their work and the imaginative spectacles they create. Nightmare already proved that Selick is a wonderful fantasist, but it's got nothing on even the middling parts of Coraline, which presents a created world that can stand alongside the finest ever put to film. If I gush, then let me gush, but I find it hard to watch the movie and not conclude that Selick is one of the greatest visionaries in contemporary cinema; every character and location in Coraline is a revelation.

And if all this weren't enough to set the film head and shoulders above any other family fantasy in recent memory, the overwhelming sense of creepiness would be. It's an easy thing for grown-ups to forget, but kids love scary stuff, especially when everything turns out fine in the end. Selick surely knows from creepy, and Coraline far outdoes his previous work in providing unmitigated nightmare fuel, even from an adult perspective: the climax, involving a skeletal spider woman in a shocking high-contrast web is one of the most genuinely unnerving things I've seen in a theater this decade. But it's not all grand statements of children's horror that make the film unsettling and creepy; one of the scenes that freaked me out the most consists of nothing but happy little mice dancing around, in a lower frame-rate than anything else has been animated in the whole movie. The jerky result is an effective early sign that something is wrong in this happy fantasy world.

Having said all that, there's one last thing that gives the film a final push into outright perfection. Coraline is the film I've been awaiting for a long time: it is a 3-D movie in which the dimensional effects aren't just a gimmick, but a vital component of the whole thing. For all that we've been told over and over again that the appeal of 3-D is the way it adds realistic depth to a film, I find it wonderfully ironic that its first truly artistic use should be so blatantly unrealistic. Without getting into the technicals of the whole thing (they're amazing, though), Coraline has two very different depths: in the "real-world" scenes, everything is much flatter than it is in the "other world" scenes, and this difference, though hardly subtle, is absorbed almost subliminally. The point, of course, is that the other world is a magical, fantastic place, much more spectacular than drab reality; so why not depict it using the most spectacular gimmick available to the modern filmmaker? I'm simplifying mightily; the key here is that Coraline is the first 3-D film I've ever seen that does not seem to exist largely as a distributor for cheap trichttps://www.alternateending.com/2009/08/1939-a-whiz-of-a-wiz.htmlkery. It is the film that proves Jeffrey Katzenberg and James Cameron right, that 3-D is a useful storytelling tool; it is the new medium's À nous la liberté (the first film to fully exploit sound), its The Wizard of Oz (color), its Yojimbo (anamorphic widescreen).

For this reason, I find myself completely unable to recommend or even think about the film in anything but its intended 3-D format. Trying to think of Coraline flat is like trying to think of Gone with the Wind in black-and-white, or a silent Meet Me in St. Louis. The story and tremendous craftsmanship are all the same, but something is lost; something that makes this film seem like one of the great cinematic revolutions of my lifetime. By all means, there's enough to the film without 3-D to make it a tremendous fantasy, and one of the best films I've seen in months; but if you have the opportunity to see it in its intended glory, that makes it absolutely essential viewing.