When it rains, the rain falls down

A review requested by Jonathan Storey, with thanks for donating to the Second Quinquennial Antagony & Ecstasy ACS Fundraiser.

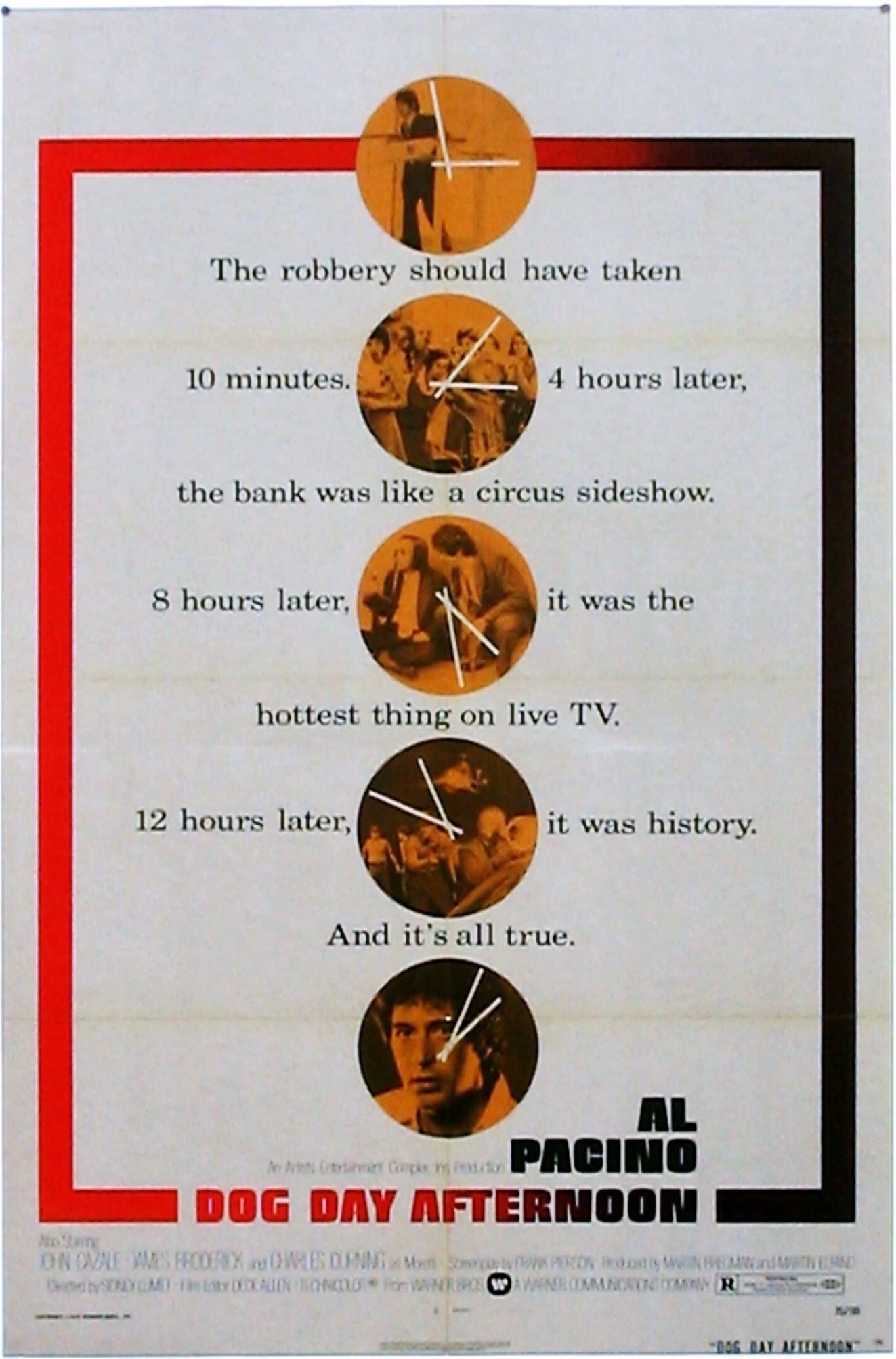

The title of the magnificent 1975 Warner Bros. release Dog Day Afternoon gives the game away: whatever else it's about, and there's a lot of things we could say it's specifically about, it's about how fucking hot it gets. 22 August, 1972, the day the true-crime story that screenwriter Frank Pierson turned into a screenplay (and which director Sidney Lumet and his cast then extensively revised through improvisation, though Pierson is the one who ended up with the film's solitary Oscar), was 81° F (~27° C) with a dewpoint of 59° F (~15° C), which is to say it was actually a rather pleasant day by late-August standards in New York City. But Dog Day Afternoon does not dick around with weather reports: it knows that the best version of its story comes from presenting a city torn against itself at a thousand fissure points, baking in the merciless sun that beats down on the asphalt and doesn't let up even when it drops below the horizon: the characters are even sweatier and more ragged at night than they were during the day. It forms one of the smallest subgenres ever with 1989's Do the Right Thing: movies in which the atmospheric oppression of summertime in New York City can magnify everybody's impatience and readiness to blow up at exactly those fissures between the people keeping society propped up and the dispossessed. Spike Lee's film called upon Public Enemy to chant "Fight the Power", Lumet's finds Al Pacino nervously and angrily sputtering "Attica! Attica!" at retreating police to the delight of a crowd of bored onlookers, and it's all just another way of saying "fuck this bullshit". Or as Lumet's next film potently frames it, "I'm mad as hell and I'm not going to take it anymore".

At its core, the story (massaged away from reality and with the main character undergoing a name change) is a good old-fashioned slice of Americana: the chestnut about criminals who make every possible mistake while regarding themselves as cool, smart operators. On that August day, Sonny Wortzik (Pacino), Sal Naturale (John Cazale), and Stevie (Gary Springer) plan to hold up a bank in Brooklyn, in and out in just minutes. The first problem is that the bank has no money - the criminals just barely missed the daily cash pickup. The second is that Sonny's impromptu backup plan involves setting the bank register on fire, and the smoke catches the attention of the cops, who quickly surround the bank. With little else to do, Sonny and Sal simply claim all the bank employees as their hostages (Stevie having jumped ship almost immediately), leaving the slightly baffled Sgt. Moretti (Charles Durning) to negotiate in the face of Sonny's increasingly colorful behavior and weird demands, all catching the attention of the media, who turn the fraught situation into a gaudy circus, dragging in Sonny's devasted mother (Judith Malina), his ex-wife Angie (Susan Peretz), and his new wife Leon (Chris Sarandon), a trans woman whose costly gender reassignment surgery, it turns out, was the motivating factor in Sonny looking to rob a bank in the first place.

With that last detail, we plunge headlong into the film's defining trait, its interest in the lives and needs of the kind of people typically left of the mass cultural narrative, but it's become clear long before that plot thread shows up (it is, in fact, presented as something of a twist, though not in the least bit prurient about it) that Dog Day Afternoon either possesses its own streak of anti-establishment energy, or it finds those who do to be thoroughly fascinating, with no moral judgment supplied. The famous "Attica!" scene doesn't come from the clear blue sky; that's not even the first reference in dialogue to the 1971 Attica State Prison riots, one of the great flashpoints for the early-'70s left-wing intelligentsia. But even more than in its specifics, the whole film brims with characters who are fed up and know that things aren't going right for them. Sonny, in his many squawks of petulant outrage, shows off his knowledge of a full list of cultural touchstones, some more absurdly wielded than others, all of which reinforce the sense that he's as much a symptom of urban helplessness as a person in his own right; this is certainly why he so quickly becomes so fascinating to the news media that latch onto the crime like lampreys, and to the crowd of people outside.

Dog Day Afternoon holds back from actually serving as a left-wing polemic; its satire aims in all directions, against Sonny's enthusiastic dimness as well as in tandem with his outrage. And its anti-police sentiments were tempered considerably by casting Durning in the role of the police representive whom we see the most of; in contrast to the spitfire Pacino and the wary, wired Cazale, Durning's calming tone of voice and relaxed features make him instantly likeable, even if he is the film's main emblem of The Man.

The main thrust instead is twofold: first , the film provides a comprehensive snapshot of a segment of the underclasses of New York at a certain moment, more of an act of gonzo journalism than a message film about social ills. Many of the best films in Lumet's career (and this is very much one of the best - among the handful of films I'd say jostle for the #2 spot in his filmography, behind his exemplary theatrical debut, 12 Angry Men) are holistic descriptions of some broad aspect of that city filtered through one colorful individual, and Dog Day Afternoon is more overt about it than most: before we meet any named character, we've been treated to a montage of the city's working class in all their aspects, set somewhat incongruously to Elton John's "Amoreena".

The other thing it does is, simply, to present a remarkable collection of human beings behaving under stress. Pacino certainly dominates the film and its subsequent decades of appreciation, and he earns that: its one of his best performances, from the moment he explodes the film's quiet, whispering opening scenes with his prattling, to the extraordinary scene where he recites his will, dripping with sweat and wearing a flat, distant look. Bbut Durning and Cazale aren't far behind him in terms of how much depth they weave into there characters with just expressions and body language - in Cazale's case, frequently doing so when he's not even in focus within the frame. The miracle of it, and where Lumet's impossibly giving direction most clearly manifests itself, is in the full sense of we get of the characters who aren't even "supposed" to matter - the bank employees, who emerge one by one out of an amorphous mass of victims to be unique personalities, worrying about their loved ones, giggling and chatting as they try to stay cool while the night marches on.

Insofar as the film is a tribute to messy, vital society, it's the way that it gives all of the hostages fully-realised personalities, leaving us with the sense that any of them could just as easily be the focal point of this exact scenario as Sonny is, that most insists on that tribute: there are no "side characters" here, just a bunch of human beings all mixed up and trying to muscle through an awful situation: awful because they're all beat down by The Man in their own way; awful because of the hard, flat sun that cinematographer Victor J. Kemper allows to blow out the windows in so many shots, and the glossy sheen of perspiration they're all wearing by the end of the movie. For all its "down with everybody" rhetoric and its willingness to caustically mock the behavior that happens within it, Dog Day Afternoon is tremendously interested in its humans, and almost generous towards them, given a very curious definition of generosity.

The title of the magnificent 1975 Warner Bros. release Dog Day Afternoon gives the game away: whatever else it's about, and there's a lot of things we could say it's specifically about, it's about how fucking hot it gets. 22 August, 1972, the day the true-crime story that screenwriter Frank Pierson turned into a screenplay (and which director Sidney Lumet and his cast then extensively revised through improvisation, though Pierson is the one who ended up with the film's solitary Oscar), was 81° F (~27° C) with a dewpoint of 59° F (~15° C), which is to say it was actually a rather pleasant day by late-August standards in New York City. But Dog Day Afternoon does not dick around with weather reports: it knows that the best version of its story comes from presenting a city torn against itself at a thousand fissure points, baking in the merciless sun that beats down on the asphalt and doesn't let up even when it drops below the horizon: the characters are even sweatier and more ragged at night than they were during the day. It forms one of the smallest subgenres ever with 1989's Do the Right Thing: movies in which the atmospheric oppression of summertime in New York City can magnify everybody's impatience and readiness to blow up at exactly those fissures between the people keeping society propped up and the dispossessed. Spike Lee's film called upon Public Enemy to chant "Fight the Power", Lumet's finds Al Pacino nervously and angrily sputtering "Attica! Attica!" at retreating police to the delight of a crowd of bored onlookers, and it's all just another way of saying "fuck this bullshit". Or as Lumet's next film potently frames it, "I'm mad as hell and I'm not going to take it anymore".

At its core, the story (massaged away from reality and with the main character undergoing a name change) is a good old-fashioned slice of Americana: the chestnut about criminals who make every possible mistake while regarding themselves as cool, smart operators. On that August day, Sonny Wortzik (Pacino), Sal Naturale (John Cazale), and Stevie (Gary Springer) plan to hold up a bank in Brooklyn, in and out in just minutes. The first problem is that the bank has no money - the criminals just barely missed the daily cash pickup. The second is that Sonny's impromptu backup plan involves setting the bank register on fire, and the smoke catches the attention of the cops, who quickly surround the bank. With little else to do, Sonny and Sal simply claim all the bank employees as their hostages (Stevie having jumped ship almost immediately), leaving the slightly baffled Sgt. Moretti (Charles Durning) to negotiate in the face of Sonny's increasingly colorful behavior and weird demands, all catching the attention of the media, who turn the fraught situation into a gaudy circus, dragging in Sonny's devasted mother (Judith Malina), his ex-wife Angie (Susan Peretz), and his new wife Leon (Chris Sarandon), a trans woman whose costly gender reassignment surgery, it turns out, was the motivating factor in Sonny looking to rob a bank in the first place.

With that last detail, we plunge headlong into the film's defining trait, its interest in the lives and needs of the kind of people typically left of the mass cultural narrative, but it's become clear long before that plot thread shows up (it is, in fact, presented as something of a twist, though not in the least bit prurient about it) that Dog Day Afternoon either possesses its own streak of anti-establishment energy, or it finds those who do to be thoroughly fascinating, with no moral judgment supplied. The famous "Attica!" scene doesn't come from the clear blue sky; that's not even the first reference in dialogue to the 1971 Attica State Prison riots, one of the great flashpoints for the early-'70s left-wing intelligentsia. But even more than in its specifics, the whole film brims with characters who are fed up and know that things aren't going right for them. Sonny, in his many squawks of petulant outrage, shows off his knowledge of a full list of cultural touchstones, some more absurdly wielded than others, all of which reinforce the sense that he's as much a symptom of urban helplessness as a person in his own right; this is certainly why he so quickly becomes so fascinating to the news media that latch onto the crime like lampreys, and to the crowd of people outside.

Dog Day Afternoon holds back from actually serving as a left-wing polemic; its satire aims in all directions, against Sonny's enthusiastic dimness as well as in tandem with his outrage. And its anti-police sentiments were tempered considerably by casting Durning in the role of the police representive whom we see the most of; in contrast to the spitfire Pacino and the wary, wired Cazale, Durning's calming tone of voice and relaxed features make him instantly likeable, even if he is the film's main emblem of The Man.

The main thrust instead is twofold: first , the film provides a comprehensive snapshot of a segment of the underclasses of New York at a certain moment, more of an act of gonzo journalism than a message film about social ills. Many of the best films in Lumet's career (and this is very much one of the best - among the handful of films I'd say jostle for the #2 spot in his filmography, behind his exemplary theatrical debut, 12 Angry Men) are holistic descriptions of some broad aspect of that city filtered through one colorful individual, and Dog Day Afternoon is more overt about it than most: before we meet any named character, we've been treated to a montage of the city's working class in all their aspects, set somewhat incongruously to Elton John's "Amoreena".

The other thing it does is, simply, to present a remarkable collection of human beings behaving under stress. Pacino certainly dominates the film and its subsequent decades of appreciation, and he earns that: its one of his best performances, from the moment he explodes the film's quiet, whispering opening scenes with his prattling, to the extraordinary scene where he recites his will, dripping with sweat and wearing a flat, distant look. Bbut Durning and Cazale aren't far behind him in terms of how much depth they weave into there characters with just expressions and body language - in Cazale's case, frequently doing so when he's not even in focus within the frame. The miracle of it, and where Lumet's impossibly giving direction most clearly manifests itself, is in the full sense of we get of the characters who aren't even "supposed" to matter - the bank employees, who emerge one by one out of an amorphous mass of victims to be unique personalities, worrying about their loved ones, giggling and chatting as they try to stay cool while the night marches on.

Insofar as the film is a tribute to messy, vital society, it's the way that it gives all of the hostages fully-realised personalities, leaving us with the sense that any of them could just as easily be the focal point of this exact scenario as Sonny is, that most insists on that tribute: there are no "side characters" here, just a bunch of human beings all mixed up and trying to muscle through an awful situation: awful because they're all beat down by The Man in their own way; awful because of the hard, flat sun that cinematographer Victor J. Kemper allows to blow out the windows in so many shots, and the glossy sheen of perspiration they're all wearing by the end of the movie. For all its "down with everybody" rhetoric and its willingness to caustically mock the behavior that happens within it, Dog Day Afternoon is tremendously interested in its humans, and almost generous towards them, given a very curious definition of generosity.

Categories: crime pictures, new hollywood cinema, satire