Border lands

If the new Israeli film Lemon Tree seems an awful lot like many other Israeli films in the last several years, it's not really hard to understand why. The big thrust in Israeli message pictures of late (much like their far less widespread counterpart, Palestinian message pictures) has been to dramatise intimate stories of what happens when two people from either side of the Israel/Palestine conflict are made to interact with each other on the level of individuals, rather than members of a country. The stories are pretty much the same, and the conclusions - that there's a lot of work to be done, but the first step is for everyone to realise that we're all just humans, after all - are pretty much the same, so if you've seen an Israeli film in recent years, you've probably seen something close enough to Lemon Tree that Eran Riklis's new film will probably give you some déjà vu. Ordinarily I'd find this all somewhat disappointing and tiresome, but I'm somewhat inclined to forgive Israeli cinema its flaws; the conflicts inspiring these films have been going on for longer than there's been an English language, after all, so if it takes a couple decades of making similar movies before the region's filmmakers have got it all out of their systems, I don't see that I have any right to get sniffy about it.

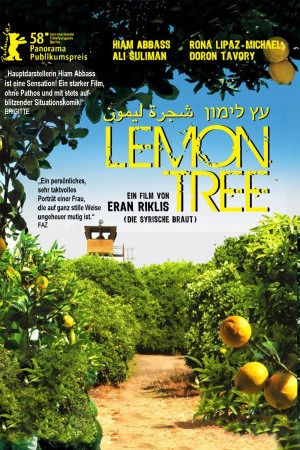

And at any rate, Lemon Tree has plenty of things going for it that justify it as an interesting, watchable movie - though not, maybe, a masterpiece - regardless of its creativity. Starting with the magnificent Hiam Abbass, an Israeli actress of Arab descent, who plays the lead role of Salma, a Palestinian widow whose house, with a vast grove of lemon trees planted by her family fifty years ago, lies just yards from the Green Line dividing Israel from the occupied West Bank. A delicate place to live, for certain, but just how awkward Salma's position is becomes clear when she gets a new pair of neighbors, the Navons: Mira (Rona Lipaz-Michael) and her husband Israel (Doron Tavory). Israel just happens to be the new Minister of Defense, and the security detail tasked with protecting him and his wife conclude after only a few days of living in the new house that the lemon grove represents an unacceptable risk; any ol' terrorist could creep in with a sniper rifle or grenade belt, the thinking goes. Thus it is that Salma receives a letter (which she cannot read, as it is in Hebrew), informing her that the Israeli government will shortly be uprooting her trees and compensating her financially. So begins a battle of wills between Salma and the edifice of Israel's bureaucracy.

That this story is meant to be read as allegory is quite plain, and it is not always the case that the allegory is effective - I should say, that at times it's not subtle enough to be clever, but is rather equivalent to being smacked over the head with a brick (in particular, I'm thinking of how the man who is responsible for Salma's suffering, who refuses to listen to the sensible, moderate advice of his wife, is named Israel). At the same time, Riklis and his co-writer Suha Arraf are obviously proud of their message, and why not? It boils down to something like, "the first step is, don't be dicks to each other", which is probably as good a bit of advice as anything else you'll hear in the torments of the Middle East.

At the same time, the movie just plain works better as a human story, centered around three great performances by Abbass, Lipaz-Michael, and Ali Suliman as the smitten lawyer who takes Salma's case all the way to the Supreme Court. One of the important things about Lemon Tree is that Salma does not particularly think of herself as a victim of vicious Israeli brutality; she just wants to protect the grove that has been in her family since before she was born, and she even possesses a certain faith that if she can but explain herself to the Israelis, they will respond to her on a human level and do right by her trees. Abbass's performance leads us into this character perfectly, suggesting a woman who isn't so much awards-baiting "Sad" as worn out and at the very end of her rope. On the other side of the fence, Lipaz-Michael demonstrates with understated grace the transformation of a woman who believes, like Salma, that people ought to just be reasonable, into a woman who has looked into a faceless patriarchy and seen the terrible truth, that people who just don't think enough about things to care if they're hurting anybody can do far more wickedness than people who are actively evil. I hesitate to say it (Abbass is one of my favorite actresses now working), but I think Lipaz-Michael even gives the greater performance, as her role has more tricky depths to it. While Salma is ever more disappointed, in a steady arc, Mira swings around from optimism to frustration slowly, but absolutely believably. It's one of the film's most unexpected and strongest choices to prevent these two women from ever actually speaking to each other, or interacting in any way more profound than a shared glance across the fence; while dramatic logic might suggest that if they joined forces, they could change everything about this situation, the truth of the film is that both women are shown to be sliding into isolation from everyone around them, and by demonstrating that they want to connect but cannot, the film gains a bit more tragedy than just "people don't get along" boilerplate.

Most of the brilliance of the film, alas, is strictly related to its script and characters; Riklis is a more than competent director (he proved that with The Syrian Bride in 2004), but much of Lemon Tree is indifferently-made at best. Or should I say, unexceptionally. Several of the shots in the film seem to be there because those are the kinds of shots you put into a movie; I was especially bothered by the way that every time we changed locations, even if it was a location we'd already seen, Riklis saw fit to give us a brand new establishing shot, filmed with a boring lack of inflection. But the problem extends to most things, except for the director's strong handling of dialogue scenes (in which he benefits incalculably from his actors); everything about this is completely by the book, as though a somewhat-gifted film student had just graduated and been handed a top-notch script. I appreciate, on the one hand, that Riklis is dedicated to avoiding easy dramatics and heavy-handed propagandising - for Lemon Tree really isn't all that propagandistic a film, presenting the hard-liners more as too pleased by the efficiency of the current way of doing things, rather than as somehow bad or mean - but the danger with trying to avoid cheap drama, and an undue level of influence over the audience, is missing drama altogether; and while the script crackles along, the visuals in Lemon Tree are powerfully uninteresting.

If that keeps it out of the top tier of Israeli movies, then so be it. It's still much smarter and more grown-up than just about anything that you could expect to find in a movie theater in the summer. If anything, its flaws are those of a filmmaker intent on letting his audience discover the film for itself, rather than being handed everything on a platter; and as sins go, that is a forgivable one.

7/10

And at any rate, Lemon Tree has plenty of things going for it that justify it as an interesting, watchable movie - though not, maybe, a masterpiece - regardless of its creativity. Starting with the magnificent Hiam Abbass, an Israeli actress of Arab descent, who plays the lead role of Salma, a Palestinian widow whose house, with a vast grove of lemon trees planted by her family fifty years ago, lies just yards from the Green Line dividing Israel from the occupied West Bank. A delicate place to live, for certain, but just how awkward Salma's position is becomes clear when she gets a new pair of neighbors, the Navons: Mira (Rona Lipaz-Michael) and her husband Israel (Doron Tavory). Israel just happens to be the new Minister of Defense, and the security detail tasked with protecting him and his wife conclude after only a few days of living in the new house that the lemon grove represents an unacceptable risk; any ol' terrorist could creep in with a sniper rifle or grenade belt, the thinking goes. Thus it is that Salma receives a letter (which she cannot read, as it is in Hebrew), informing her that the Israeli government will shortly be uprooting her trees and compensating her financially. So begins a battle of wills between Salma and the edifice of Israel's bureaucracy.

That this story is meant to be read as allegory is quite plain, and it is not always the case that the allegory is effective - I should say, that at times it's not subtle enough to be clever, but is rather equivalent to being smacked over the head with a brick (in particular, I'm thinking of how the man who is responsible for Salma's suffering, who refuses to listen to the sensible, moderate advice of his wife, is named Israel). At the same time, Riklis and his co-writer Suha Arraf are obviously proud of their message, and why not? It boils down to something like, "the first step is, don't be dicks to each other", which is probably as good a bit of advice as anything else you'll hear in the torments of the Middle East.

At the same time, the movie just plain works better as a human story, centered around three great performances by Abbass, Lipaz-Michael, and Ali Suliman as the smitten lawyer who takes Salma's case all the way to the Supreme Court. One of the important things about Lemon Tree is that Salma does not particularly think of herself as a victim of vicious Israeli brutality; she just wants to protect the grove that has been in her family since before she was born, and she even possesses a certain faith that if she can but explain herself to the Israelis, they will respond to her on a human level and do right by her trees. Abbass's performance leads us into this character perfectly, suggesting a woman who isn't so much awards-baiting "Sad" as worn out and at the very end of her rope. On the other side of the fence, Lipaz-Michael demonstrates with understated grace the transformation of a woman who believes, like Salma, that people ought to just be reasonable, into a woman who has looked into a faceless patriarchy and seen the terrible truth, that people who just don't think enough about things to care if they're hurting anybody can do far more wickedness than people who are actively evil. I hesitate to say it (Abbass is one of my favorite actresses now working), but I think Lipaz-Michael even gives the greater performance, as her role has more tricky depths to it. While Salma is ever more disappointed, in a steady arc, Mira swings around from optimism to frustration slowly, but absolutely believably. It's one of the film's most unexpected and strongest choices to prevent these two women from ever actually speaking to each other, or interacting in any way more profound than a shared glance across the fence; while dramatic logic might suggest that if they joined forces, they could change everything about this situation, the truth of the film is that both women are shown to be sliding into isolation from everyone around them, and by demonstrating that they want to connect but cannot, the film gains a bit more tragedy than just "people don't get along" boilerplate.

Most of the brilliance of the film, alas, is strictly related to its script and characters; Riklis is a more than competent director (he proved that with The Syrian Bride in 2004), but much of Lemon Tree is indifferently-made at best. Or should I say, unexceptionally. Several of the shots in the film seem to be there because those are the kinds of shots you put into a movie; I was especially bothered by the way that every time we changed locations, even if it was a location we'd already seen, Riklis saw fit to give us a brand new establishing shot, filmed with a boring lack of inflection. But the problem extends to most things, except for the director's strong handling of dialogue scenes (in which he benefits incalculably from his actors); everything about this is completely by the book, as though a somewhat-gifted film student had just graduated and been handed a top-notch script. I appreciate, on the one hand, that Riklis is dedicated to avoiding easy dramatics and heavy-handed propagandising - for Lemon Tree really isn't all that propagandistic a film, presenting the hard-liners more as too pleased by the efficiency of the current way of doing things, rather than as somehow bad or mean - but the danger with trying to avoid cheap drama, and an undue level of influence over the audience, is missing drama altogether; and while the script crackles along, the visuals in Lemon Tree are powerfully uninteresting.

If that keeps it out of the top tier of Israeli movies, then so be it. It's still much smarter and more grown-up than just about anything that you could expect to find in a movie theater in the summer. If anything, its flaws are those of a filmmaker intent on letting his audience discover the film for itself, rather than being handed everything on a platter; and as sins go, that is a forgivable one.

7/10