Smiles of a summer night

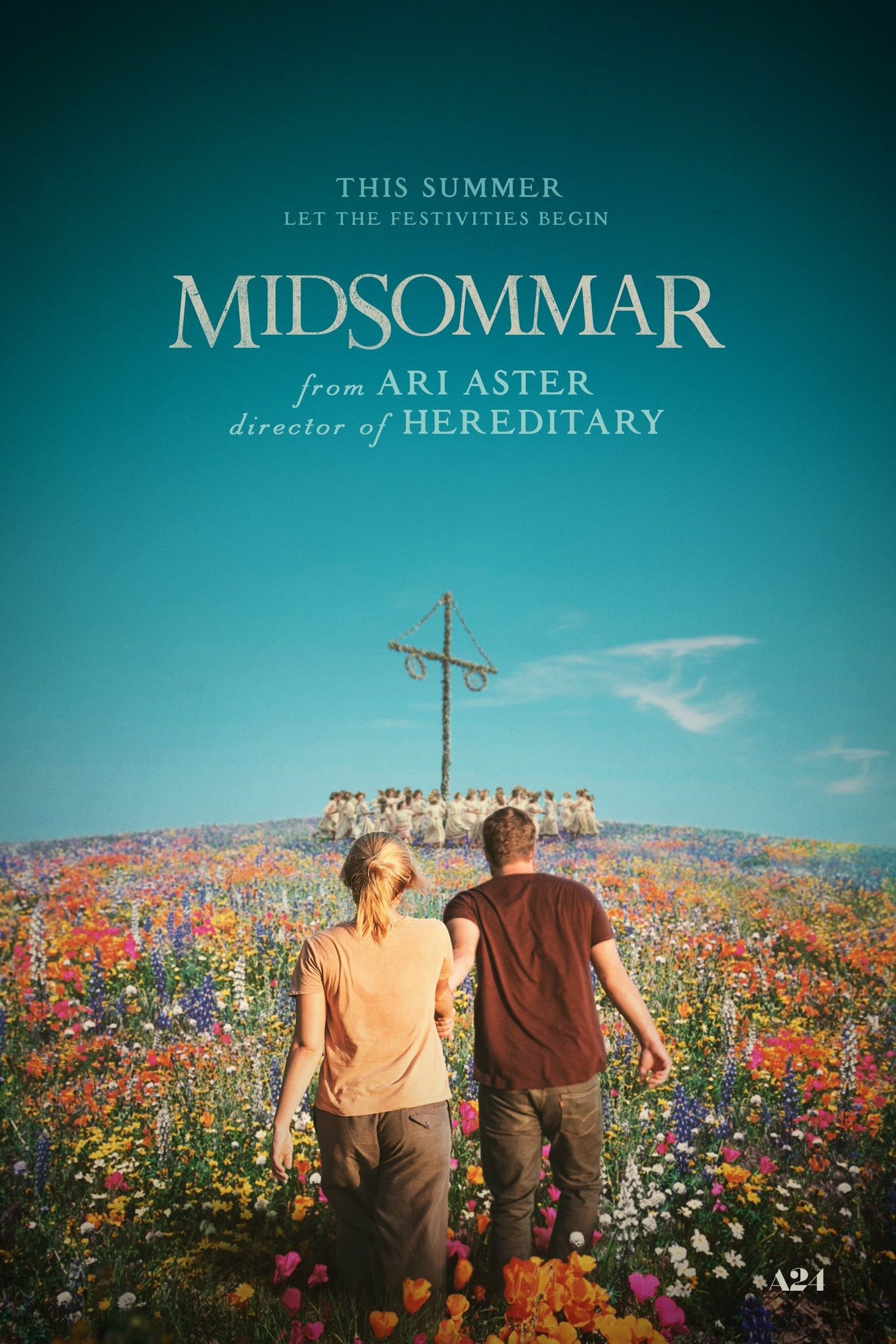

There are multiple versions of 1973's The Wicker Man, but the one that has been easiest to see for most of the film's existence is 88 minutes long. This might not matter, since you're not reading a review of The Wicker Man, but here's the thing: Midsommar is basically The Wicker Man with the serial numbers sanded off (but not very well, or with much motivation), and the theme of toxic religious conservatism replaced by a theme of toxic romantic relationships and male entitlement therein. It is fair to say that they are doing 80% of the same thing in 80% of the same way, and part of that 20% is that Midsommar is 147 minutes long. I'll do the math for you: 59 minutes, or basically an hour. It's not time well-spent.

In fact, it is time spent so ill that you could probably cut the first 20 minutes right off of Midsommar, and only have to tweak one or two lines of dialogue for it to still make perfect sense and cover exactly the same psychological ground. And you would still have a movie that's too motherfucking long, though at least at that point it would merely be "too long" instead of the hallucinatory pretentious impossibility of this scenario somehow dragging its bloated ass all the way to two hours and twenty-seven god-be-damned minutes.

Said scenario begins, naturally enough, in the dead of winter, on a night when Dani (Florence Pugh) is freaking out a cryptic e-mail from her sister that, read in a certain light, suggests the possibility of self-harm or worse. She keeps calling her boyfriend, Christian (Jack Reynor), who is playing poker with his fellow anthropology grad students Josh (William Jackson Harper), Pelle (Vilhelm Blogren), and Mark (Will Poulter), and through them we learn that Christian has been emotionally checked-out of this relationship for a very long time, and they all want very badly for him to simply cut ties already. But something - guilt is the only obvious explanation, but he doesn't seem like much of a guilty sort - keeps him tethered to the phone, patiently and condescendingly listening to here freaking out. Turns out that she should be: her sister has killed herself and the girls' parents with carbon monoxide poisoning.

Six months later - so, nearly midsummer, if you're keeping track - Dani and Christian are still together, no more happily; he has, in fact, been secretly planning a two-week trip to Sweden with the other guys, and she only finds out by pure accident. He invites her along, expecting her to say no; she accepts, not really wanting to go, but thinking he wants her there. Once in Sweden, a place where she feels totally uncomfortable and confused on top of the perpetual risk of depression swinging in to knock her for a loop, Dani has an opportunity to really just sink into the knowledge of what a shitty situation she's stuck in, amplified by the open interest some of the local girls express in Christian.

Ari Aster, the writer and director of Midsommar - it is his second feature, after last year's Hereditary - has made it very clear that he thinks this is a film primarily about being stalled out in a toxic, emotionally unhealthy relationship, and from all that I've written, it mostly likely sounds like he's right. Hell, he is right. The problem is that his film shouldn't be a study of a terrible relationship, because that part of it frankly doesn't work much at all. Aster's script for Midsommar is a bit of a fever swamp, plugging in fragments of character arcs and isolated shards of character backstory and altogether failing to sketch either Dani or Christian in the kind of detail needed to make their relationship anything other than a writerly conceit. This is made worse by how clearly the film thinks it has done this work: all the material about Dani's dead family, portrayed at some length and with a level of dreamy nightmarish detail that amply reminds us that Aster can be a great horror director when he's aiming to, is clearly supposed to inform the entire rest of her arc. It is, however, drawn in only in the most rudimentary, arbitrary way: when the film wants her to be a trauma-haunted orphan she is, and when it has anything else going on, it isn't even an echo in the character's behavior or Pugh's performance. This is a particularly galling example of the film's overall problem with not letting these characters have fully-developed inner lives: they behave the way the script needs them to behave, whether it fits their personality or not. Which is to say, they don't have personalities, just tics and behaviors.

That's an enormous problem for a character drama; it barely even registers as a concern of a paranoid, atmospheric horror movie, so the good news for Midsommar is that, when it's not failing to be the bracing break-up movie of Aster's dreams, it's succeeding at being a genre film. It's giving away nothing that's not obvious within minutes that the Swedish commune where Pelle takes his four American friends after the bloated first act, in celebration of the every-90-years fertility festival going on this particular year, has something rather more menacing on its mind than is apparent at first glance (and not just because I already told you that this is a Wicker Man knock-off). And for a very large overall percentage of its running time, the film is absolutely happy to do nothing but watch in alarm as the commune reveals its deadly side at great length. Midsommar comes close to doing something brand new to me in screen horror: it extracts exhausting, bone-deep tension and moody terror out of aggressively bright, sunlit exteriors, full of richly saturated colors against a color palette that overall skews towards bright, searing whites. Pawel Pogorzelski, Aster's cinematographer since their film school days, has created a striking, original look of sun-blasted landscapes mixing with interior so cool in their blue-black-brown hues that you can almost smell the clammy summer damp leeching off them.

It is a superb evocation of the nightless days around the summer solstice in Scandinavia, a place and time whose ethereal wrongness has only rarely been exploited by filmmakers at all, let alone horror filmmakers (Ingmar Bergman prominently used the phenomenon of midnight sun twice, in Smiles of a Summer Night and Persona, but neither of those seems to be foremost among Aster's influences). Midsommar runs with it, turning daylight into some oppressive and hideous. Couple that with Aster's fantastic staging of the commune's behavior and religious rites, as calm, quiet, orderly arrangements of geometry, and the film starts to become something extremely special. And then add in the brazen use of sound, with everything unpleasantly over-loud and mixed to all the surrounds to feel like we're under assault from basically every sound effect in the natural world, and the film starts to look like an outright masterpiece of place-setting and uncanny atmosphere, from its dizzying warp effects during the drug trips that keep laying Dani low to a frantic maypole sequence near the end that is a masterpiece of hallucinatory subjectivity, to the handful of bursts of some of the most realistic violence I've seen in many a day.

It is, in short, a rich and unnerving mood piece and mental horror picture. Then why insist on foregrounding the non-starter of a relationship drama? Why try to tease out themes of female passivity and male entitlement that have to fight for every inch against how flat and undercooked the characters are? Why do any of this in a vessel that's a soul-crushing 147 minutes long, fully half an hour past even the most indulgent running time for this sort of material that would likely have worked? I cannot answer any of these questions; I can only say that they add up to enough frustrations and gaping flaws with the movie that Midsommar somehow manages to barely rise up to the level of "eh, it's watchable" despite having individual scenes as good as any horror movie of the 2010s. But that's it, maybe: when a film is this disjointed and underwritten, it's only individual scenes, adding up to nothing, and a huge fucking stretch of nothing at that.

In fact, it is time spent so ill that you could probably cut the first 20 minutes right off of Midsommar, and only have to tweak one or two lines of dialogue for it to still make perfect sense and cover exactly the same psychological ground. And you would still have a movie that's too motherfucking long, though at least at that point it would merely be "too long" instead of the hallucinatory pretentious impossibility of this scenario somehow dragging its bloated ass all the way to two hours and twenty-seven god-be-damned minutes.

Said scenario begins, naturally enough, in the dead of winter, on a night when Dani (Florence Pugh) is freaking out a cryptic e-mail from her sister that, read in a certain light, suggests the possibility of self-harm or worse. She keeps calling her boyfriend, Christian (Jack Reynor), who is playing poker with his fellow anthropology grad students Josh (William Jackson Harper), Pelle (Vilhelm Blogren), and Mark (Will Poulter), and through them we learn that Christian has been emotionally checked-out of this relationship for a very long time, and they all want very badly for him to simply cut ties already. But something - guilt is the only obvious explanation, but he doesn't seem like much of a guilty sort - keeps him tethered to the phone, patiently and condescendingly listening to here freaking out. Turns out that she should be: her sister has killed herself and the girls' parents with carbon monoxide poisoning.

Six months later - so, nearly midsummer, if you're keeping track - Dani and Christian are still together, no more happily; he has, in fact, been secretly planning a two-week trip to Sweden with the other guys, and she only finds out by pure accident. He invites her along, expecting her to say no; she accepts, not really wanting to go, but thinking he wants her there. Once in Sweden, a place where she feels totally uncomfortable and confused on top of the perpetual risk of depression swinging in to knock her for a loop, Dani has an opportunity to really just sink into the knowledge of what a shitty situation she's stuck in, amplified by the open interest some of the local girls express in Christian.

Ari Aster, the writer and director of Midsommar - it is his second feature, after last year's Hereditary - has made it very clear that he thinks this is a film primarily about being stalled out in a toxic, emotionally unhealthy relationship, and from all that I've written, it mostly likely sounds like he's right. Hell, he is right. The problem is that his film shouldn't be a study of a terrible relationship, because that part of it frankly doesn't work much at all. Aster's script for Midsommar is a bit of a fever swamp, plugging in fragments of character arcs and isolated shards of character backstory and altogether failing to sketch either Dani or Christian in the kind of detail needed to make their relationship anything other than a writerly conceit. This is made worse by how clearly the film thinks it has done this work: all the material about Dani's dead family, portrayed at some length and with a level of dreamy nightmarish detail that amply reminds us that Aster can be a great horror director when he's aiming to, is clearly supposed to inform the entire rest of her arc. It is, however, drawn in only in the most rudimentary, arbitrary way: when the film wants her to be a trauma-haunted orphan she is, and when it has anything else going on, it isn't even an echo in the character's behavior or Pugh's performance. This is a particularly galling example of the film's overall problem with not letting these characters have fully-developed inner lives: they behave the way the script needs them to behave, whether it fits their personality or not. Which is to say, they don't have personalities, just tics and behaviors.

That's an enormous problem for a character drama; it barely even registers as a concern of a paranoid, atmospheric horror movie, so the good news for Midsommar is that, when it's not failing to be the bracing break-up movie of Aster's dreams, it's succeeding at being a genre film. It's giving away nothing that's not obvious within minutes that the Swedish commune where Pelle takes his four American friends after the bloated first act, in celebration of the every-90-years fertility festival going on this particular year, has something rather more menacing on its mind than is apparent at first glance (and not just because I already told you that this is a Wicker Man knock-off). And for a very large overall percentage of its running time, the film is absolutely happy to do nothing but watch in alarm as the commune reveals its deadly side at great length. Midsommar comes close to doing something brand new to me in screen horror: it extracts exhausting, bone-deep tension and moody terror out of aggressively bright, sunlit exteriors, full of richly saturated colors against a color palette that overall skews towards bright, searing whites. Pawel Pogorzelski, Aster's cinematographer since their film school days, has created a striking, original look of sun-blasted landscapes mixing with interior so cool in their blue-black-brown hues that you can almost smell the clammy summer damp leeching off them.

It is a superb evocation of the nightless days around the summer solstice in Scandinavia, a place and time whose ethereal wrongness has only rarely been exploited by filmmakers at all, let alone horror filmmakers (Ingmar Bergman prominently used the phenomenon of midnight sun twice, in Smiles of a Summer Night and Persona, but neither of those seems to be foremost among Aster's influences). Midsommar runs with it, turning daylight into some oppressive and hideous. Couple that with Aster's fantastic staging of the commune's behavior and religious rites, as calm, quiet, orderly arrangements of geometry, and the film starts to become something extremely special. And then add in the brazen use of sound, with everything unpleasantly over-loud and mixed to all the surrounds to feel like we're under assault from basically every sound effect in the natural world, and the film starts to look like an outright masterpiece of place-setting and uncanny atmosphere, from its dizzying warp effects during the drug trips that keep laying Dani low to a frantic maypole sequence near the end that is a masterpiece of hallucinatory subjectivity, to the handful of bursts of some of the most realistic violence I've seen in many a day.

It is, in short, a rich and unnerving mood piece and mental horror picture. Then why insist on foregrounding the non-starter of a relationship drama? Why try to tease out themes of female passivity and male entitlement that have to fight for every inch against how flat and undercooked the characters are? Why do any of this in a vessel that's a soul-crushing 147 minutes long, fully half an hour past even the most indulgent running time for this sort of material that would likely have worked? I cannot answer any of these questions; I can only say that they add up to enough frustrations and gaping flaws with the movie that Midsommar somehow manages to barely rise up to the level of "eh, it's watchable" despite having individual scenes as good as any horror movie of the 2010s. But that's it, maybe: when a film is this disjointed and underwritten, it's only individual scenes, adding up to nothing, and a huge fucking stretch of nothing at that.