The family business

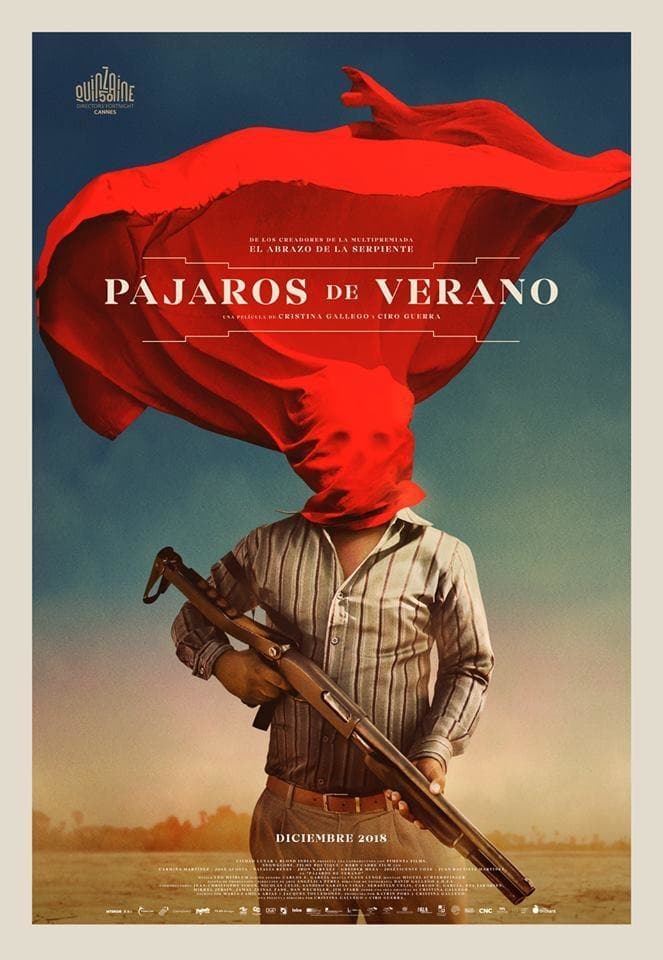

2015's Embrace of the Serpent, director Ciro Guerra's third film, was a story of indigenous traditions in Colombia being corrupted and overwritten by an encounter with Westerners. It's also one of the most remarkable sui generis films of the 2010s, a film that takes place in history but also feels outside of it; draws upon art film techniques decades old while refashioning them into something that challenges European norms in its style as much as it does in its narrative; has an otherworldly, dreamy beauty, while also commanding a great deal of immediate presence. And that's not a fair standard to hold any filmmaker to, but I'm going to anyway. Because here comes Birds of Passage, Guerra's fourth film, this time co-directed with Serpent's producer, Cristina Gallego (she also wrote the film's scenario), and it is also a story of indigenous traditions in Colombia being corrupted and overwritten by an encounter with Westerners. But now, instead of re-writing the possibilities of cinematic storytelling right before our dazzled eyes, Birds of Passage is... basically, it's The Godfather. Or The Godfather, Part II, if we want to be more precise. Or Goodfellas, or the 1983 Scarface if we want to talk about bad movies that are famous, or 2001's Blow if we want to talk about bad movies that have been forgotten. Or... I could go on, is the point.

In short, Birds of Passage is a "rise and fail of a young gangster's drug empire, plus the fortunes of his family" picture, not so far as I am aware "based on" a true story, but certainly pointing in the direction of truth of how Colombia was swept up into the international drug trade in the 1970s. Not a new subject for cinema by even the most generous stretch of the imagination, and there's really not much of anything in Maria Camila Arias & Jacques Toulemonde's screenplay to make it pretend to be new; nor does José Acosta's lead performance as Rapayet, the determined innocent-turned overbearing hothead who makes all the money and causes all the trouble push in startling new directions from the basic template of intemperate young men who have been getting themselves all wrapped up in organised crime since the very first months of sound cinema.

Granting all of that - and I think it is a lot to grant - Birds of Passage still manages to distinguish itself in one hugely important way: its setting is more or less entirely unique, I think (the IMDb suggests that it is the only film ever made in the Wayuu language, which serves at least as a proxy). The film takes place among the Wayuu people of northern Colombia and Venezuela, a clan-based indigenous group that remained unusually impermeable to influence from the alijuna (anyone with European ancestry) through the middle part of the 20th Century. This means that much of the story is not merely about Rapayet's flirtation with dangerous criminality; it's about the effect that flirtation has on the particular cadences of Wayuu life in the clan run by his mother-in-law, Úrsula (Carmiña Martínez). The five-part story, spanning about 15 years in the 1960s and 1970s, tracks the increments by which the traditions we witness in the protracted opening sequence are replaced by gang wars with Western weaponry.

Like all the best movies set in cinematically-unknown indigenous cultures, Birds of Passage isn't looking to be an ethnography. The film does not take the perspective of an outsider to any of this, teaching us how Wayuu lore works, what the rules are governing hierarchies and behavior, or any such thing. It just starts, and we either pick it up as we go along or not. This yields immediate benefits: the film's opening sequence is its best part, depicting the coming-of-age ritual for Úrsula's daughter Zaida (Natalia Reyes), culminating in a series of symbolic dances by which men try and fail to court her. The ritual isn't the point; the ritual is taken for granted, so that the film can instead focus on the psychological warfare between Rapayet and Úrsula, who immediately recognises that the young man will be of no good to her clan, herself, or especially her daughter. But he promises to devote himself to meeting her usurious demands for a dowry, and to do it, he calls upon his alijuna friend Moisés (Jhon Narváez) to help him set up an arrangement with some dimwitted white Peace Corps members in Colombia that year. A few dozen pounds of marijuana later, Rapayet has his dowry, and one particular white man has an idea that if Rapayet wants to make some real money...

So far, so ingenious and intoxicating and visually striking and sonically transporting. The last two things, at least, never go away: David Gallego's cinematography captures the hard lighting of the arid Guajira peninsula as a striking combination of crisp shadows and blazingly bright colors from start to finish; heck, the film's look even gets better as it goes along, culminating in some immensely powerful storm clouds on the horizon. And Leo Heiblum's music, which might for all I know draw from Wayuu motifs, provides an irresistibly rhythmic structure for the stillness of traditional life, before speeding up and erupting in the more Westernised violent sequences.

The thing is, for all the smartness of its craft, and Gallego & Guerra's fine management of a good cast, this is awfully familiar stuff. The film's Big Claims - capitalism kills, greed eats your soul, simplicity and tradition are maybe boring and static, but at least they're predictable and don't end in bloodshed - are clichés through and through, and so, increasingly, are the character relationships. When Úrsula is onscreen, the film remains in focus: her implacability that softens and turns into greed, even as she knows with every breath that a reckoning will come due, that is the film, and Martínez is also giving the best performance as this ambivalent, internally-wracked figure. But Rapayet, for all that he's precisely-conceived and specific, is a lot like a lot of characters; his relationship with Moisés, in particular, is the exact same "one is mercurial but has his head on his shoulders, one is a possibly psychopathic loose cannon" relationship of goddamn near every gangster movie on the books. And for all her prominence in the early going - including being the focal point for a long opening scene - Zaida flattens out entirely well before the film is over.

Where the film shines is where it contrasts its genre stereotypes with the mysticism of the Wayuu lifestyle, which is part of why it's so brilliant that it refuses to explain that lifestyle for the audience: the aberration is Westernisation, not tradition, and that comes through clearer by letting the tradition speak for itself. Still, even that's all a bit clichéd in the broad strokes, and there's less of it with every passing one of the film's chapters. I am aware of being hard on this film, which I do very much admire in almost all ways, and love in more than a couple. But admiring a thing is not the same as being impressed by it, and Birds of Passage is just not nearly as interesting a movie as it really ought to be.

In short, Birds of Passage is a "rise and fail of a young gangster's drug empire, plus the fortunes of his family" picture, not so far as I am aware "based on" a true story, but certainly pointing in the direction of truth of how Colombia was swept up into the international drug trade in the 1970s. Not a new subject for cinema by even the most generous stretch of the imagination, and there's really not much of anything in Maria Camila Arias & Jacques Toulemonde's screenplay to make it pretend to be new; nor does José Acosta's lead performance as Rapayet, the determined innocent-turned overbearing hothead who makes all the money and causes all the trouble push in startling new directions from the basic template of intemperate young men who have been getting themselves all wrapped up in organised crime since the very first months of sound cinema.

Granting all of that - and I think it is a lot to grant - Birds of Passage still manages to distinguish itself in one hugely important way: its setting is more or less entirely unique, I think (the IMDb suggests that it is the only film ever made in the Wayuu language, which serves at least as a proxy). The film takes place among the Wayuu people of northern Colombia and Venezuela, a clan-based indigenous group that remained unusually impermeable to influence from the alijuna (anyone with European ancestry) through the middle part of the 20th Century. This means that much of the story is not merely about Rapayet's flirtation with dangerous criminality; it's about the effect that flirtation has on the particular cadences of Wayuu life in the clan run by his mother-in-law, Úrsula (Carmiña Martínez). The five-part story, spanning about 15 years in the 1960s and 1970s, tracks the increments by which the traditions we witness in the protracted opening sequence are replaced by gang wars with Western weaponry.

Like all the best movies set in cinematically-unknown indigenous cultures, Birds of Passage isn't looking to be an ethnography. The film does not take the perspective of an outsider to any of this, teaching us how Wayuu lore works, what the rules are governing hierarchies and behavior, or any such thing. It just starts, and we either pick it up as we go along or not. This yields immediate benefits: the film's opening sequence is its best part, depicting the coming-of-age ritual for Úrsula's daughter Zaida (Natalia Reyes), culminating in a series of symbolic dances by which men try and fail to court her. The ritual isn't the point; the ritual is taken for granted, so that the film can instead focus on the psychological warfare between Rapayet and Úrsula, who immediately recognises that the young man will be of no good to her clan, herself, or especially her daughter. But he promises to devote himself to meeting her usurious demands for a dowry, and to do it, he calls upon his alijuna friend Moisés (Jhon Narváez) to help him set up an arrangement with some dimwitted white Peace Corps members in Colombia that year. A few dozen pounds of marijuana later, Rapayet has his dowry, and one particular white man has an idea that if Rapayet wants to make some real money...

So far, so ingenious and intoxicating and visually striking and sonically transporting. The last two things, at least, never go away: David Gallego's cinematography captures the hard lighting of the arid Guajira peninsula as a striking combination of crisp shadows and blazingly bright colors from start to finish; heck, the film's look even gets better as it goes along, culminating in some immensely powerful storm clouds on the horizon. And Leo Heiblum's music, which might for all I know draw from Wayuu motifs, provides an irresistibly rhythmic structure for the stillness of traditional life, before speeding up and erupting in the more Westernised violent sequences.

The thing is, for all the smartness of its craft, and Gallego & Guerra's fine management of a good cast, this is awfully familiar stuff. The film's Big Claims - capitalism kills, greed eats your soul, simplicity and tradition are maybe boring and static, but at least they're predictable and don't end in bloodshed - are clichés through and through, and so, increasingly, are the character relationships. When Úrsula is onscreen, the film remains in focus: her implacability that softens and turns into greed, even as she knows with every breath that a reckoning will come due, that is the film, and Martínez is also giving the best performance as this ambivalent, internally-wracked figure. But Rapayet, for all that he's precisely-conceived and specific, is a lot like a lot of characters; his relationship with Moisés, in particular, is the exact same "one is mercurial but has his head on his shoulders, one is a possibly psychopathic loose cannon" relationship of goddamn near every gangster movie on the books. And for all her prominence in the early going - including being the focal point for a long opening scene - Zaida flattens out entirely well before the film is over.

Where the film shines is where it contrasts its genre stereotypes with the mysticism of the Wayuu lifestyle, which is part of why it's so brilliant that it refuses to explain that lifestyle for the audience: the aberration is Westernisation, not tradition, and that comes through clearer by letting the tradition speak for itself. Still, even that's all a bit clichéd in the broad strokes, and there's less of it with every passing one of the film's chapters. I am aware of being hard on this film, which I do very much admire in almost all ways, and love in more than a couple. But admiring a thing is not the same as being impressed by it, and Birds of Passage is just not nearly as interesting a movie as it really ought to be.