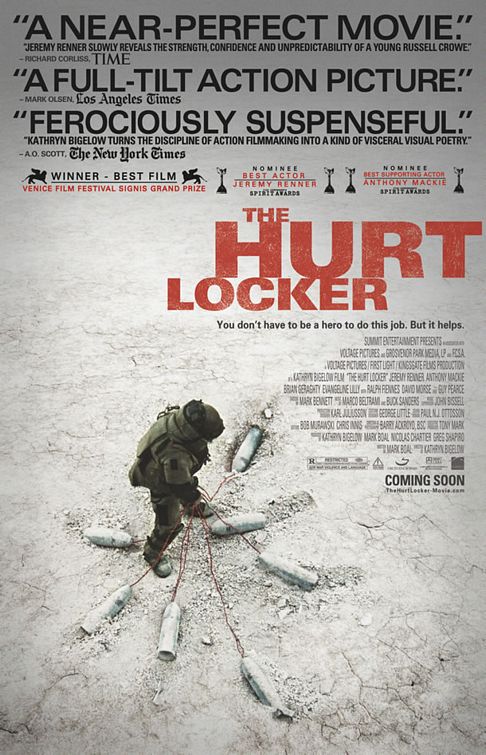

Man of war

François Truffaut once famously suggested that there could never be a truly anti-war film, because film by its nature makes whatever it is depicting seem exciting. This generally sound theory has been violated since he first voiced it (and really, already had been before that; has anyone ever walked out of Grand Illusion thinking to themselves, "Boy howdy, it does seem to me that war is both fun and invigorating"?), but it is given a particularly interesting workout by director Kathryn Bigelow's The Hurt Locker, the latest attempt to make audiences give a damn about the Iraq War. This film certainly does not make warfare seem all that exciting; it seems instead to be stretched-out moments of terror punctuated by instants of blissful relief when you somehow manage to remain not dead. At the same time, it must be honest to its protagonist, an explosives expert who gets a distinct and unambiguous rush from his acts of death-defying heroism, and by yoking itself to his POV, the film allows us to experience, somewhat the same pleasant adrenaline spike. As the epigraph by Chris Hedges that opens the movie puts it, war is a drug.

Set in Baghdad in an ostensible 2004 that is positively rotten with anachronisms, The Hurt Locker is the story of a three-man Explosive Ordinance Disposal (EOD) team whose job is to hunt and eliminate IEDs, those nasty bits of business that were such a prominent feature of news stories back in the days before the war got shuffled off the front page by the economy (hah, I tease, the war wasn't infotaining enough to ever hold a secure place on the front page): Staff Sergeant James (Jeremy Renner), the uncontrollable technician whose desire to defuse bombs borders on the pathological, and puts his life in basically constant jeopardy; Sergeant Sanborn (Anthony Mackie), his subordinate who is in charge of keeping an eye on the surrounding situation while James is at the bomb; and Specialist Eldridge (Brian Geraghty), who basically does the same thing as Sanborn but is still too shaken up from the explosive death of their previous CO, Sergeant Thompson (a cameoing Guy Pearce) to fully engage with what he's doing.

The film achieves a kind of platonic ideal: it is about nothing but the experience of being a soldier, no editorialising or hand-wringing to be found. That experience, in the film's eyes, has two facets: one can either try to play things as safe as humanly possible in the least-safe place imaginable, just trying to keep alive long enough to get home, and be like Sanborn; or one can embrace the danger of the moment and feed off it, and use that danger to inspire one to greater achievements, liek James. Neither man is vilified for his position - when Sanborn declares, apparently without a hint of sarcasm or hesitation, that he would just soon kill James as follow him yet again into a reckless, potentially lethal situation, we can understand him without agreeing that it is the right thing to do, nor finding ourselves shocked at his murderous rage. This is just the way things are, the film argues with tremendous effectiveness (the writer, Mark Boal, was embedded with an actual EOD team in Iraq), and it's all so hellish and disorienting and awful that nobody could expect to remain a placid, zen-like individual in the midst of it all. If the film has an ideological bent, it's neither pro- nor anti-war, but simply pro-soldier; agree with their mission or not (Bigelow and Boal do not even once invite us to take such a stance), but you have to respect their willingness, every day, to risk dying a violent and painful death.

The film advances this argument in two ways, one mostly successful, the other a bit less. In the first, there are its celebrated action sequences, though action is hardly the right word. I just don't know what else to call them. Basically the story of the movie is one event repeated over and over: a call comes in, the EOD team drives out to some alley or road where an explosive has been secreted, and James hops out in his bulky, restrictive suit to waddle over to the bomb and stop it from exploding. Most of the time, he does something along the way to drive Sanborn crazy, as the sergeant does not agree with their higher-ups that James is some kind of inspired hellcat (the higher-ups, of course, are not in immediate danger of blowing up along with him). It's fair to say that the bulk of this 131 minute film consists of the pregnant wait in the time between the team identifying the bomb and James successfully defusing it; agonising minutes waiting for something awful to happen. These sequences are put together with absolutely impeccable craftsmanship; my only previous context for Bigelow's direction was the faintly awful K-19: The Widowmaker, which suggested very little good about her talents, but then here she had to go and make something to prove me all sorts of wrong. What's amazing about the many tense moments in The Hurt Locker is how few of the customary tricks used to generate tension: there are no urgent close-ups or pounding drums or rapid-fire cuts. The most shocking thing about the movie, really, is how much of it takes place in lingering medium shots. Only the slightly intrusive use of hand-held camera, its characteristic wobbliness insisting "REALISM!" while just coming off as stale, threatens to puncture the uncanny effectiveness of these moments.

We're right there with the characters: it's terrifying and we absolutely know that things are going to go wrong, but it's kind of thrilling and fun anyway. I could take or leave the extended "hunt through Baghdad at night" sequence near the end, demonstrating how James's experiences have started to unravel his mind; the protracted pauses when we're waiting for the "boom" have more than done explained what we needed to know.

And that's where the film starts to wander into its more awkward territory. The filmmakers, it seems, do not believe that they are very good at their jobs; that we intuitively understand what's going on from the impact on ourselves as viewers from those masterful bomb-defusing sequences. So they explain everything, in the most explicit detail you could imagine; starting with that very same epigraph, all the way to the penultimate scene. Basically, this is one of those movies that is extremely good whenever characters keep their mouths shut; when there's dialogue, it's usually heavy-handed and leading. A shame, because the more-than-able cast - especially Renner, who has cropped up here and there in various things, and whose face communicates everything we could ever hope to know about James - doesn't need Bigelow and Boal whispering in the audience's ear to get their characters across. It's frankly damned annoying, and turns what could have been a truly marvelous war picture into a kind of harangue, at times; moments of intensity punctuated by lectures. Does it make The Hurt Locker a failure? Lord no, but it does mean that at the very best, it's a qualified success.

Set in Baghdad in an ostensible 2004 that is positively rotten with anachronisms, The Hurt Locker is the story of a three-man Explosive Ordinance Disposal (EOD) team whose job is to hunt and eliminate IEDs, those nasty bits of business that were such a prominent feature of news stories back in the days before the war got shuffled off the front page by the economy (hah, I tease, the war wasn't infotaining enough to ever hold a secure place on the front page): Staff Sergeant James (Jeremy Renner), the uncontrollable technician whose desire to defuse bombs borders on the pathological, and puts his life in basically constant jeopardy; Sergeant Sanborn (Anthony Mackie), his subordinate who is in charge of keeping an eye on the surrounding situation while James is at the bomb; and Specialist Eldridge (Brian Geraghty), who basically does the same thing as Sanborn but is still too shaken up from the explosive death of their previous CO, Sergeant Thompson (a cameoing Guy Pearce) to fully engage with what he's doing.

The film achieves a kind of platonic ideal: it is about nothing but the experience of being a soldier, no editorialising or hand-wringing to be found. That experience, in the film's eyes, has two facets: one can either try to play things as safe as humanly possible in the least-safe place imaginable, just trying to keep alive long enough to get home, and be like Sanborn; or one can embrace the danger of the moment and feed off it, and use that danger to inspire one to greater achievements, liek James. Neither man is vilified for his position - when Sanborn declares, apparently without a hint of sarcasm or hesitation, that he would just soon kill James as follow him yet again into a reckless, potentially lethal situation, we can understand him without agreeing that it is the right thing to do, nor finding ourselves shocked at his murderous rage. This is just the way things are, the film argues with tremendous effectiveness (the writer, Mark Boal, was embedded with an actual EOD team in Iraq), and it's all so hellish and disorienting and awful that nobody could expect to remain a placid, zen-like individual in the midst of it all. If the film has an ideological bent, it's neither pro- nor anti-war, but simply pro-soldier; agree with their mission or not (Bigelow and Boal do not even once invite us to take such a stance), but you have to respect their willingness, every day, to risk dying a violent and painful death.

The film advances this argument in two ways, one mostly successful, the other a bit less. In the first, there are its celebrated action sequences, though action is hardly the right word. I just don't know what else to call them. Basically the story of the movie is one event repeated over and over: a call comes in, the EOD team drives out to some alley or road where an explosive has been secreted, and James hops out in his bulky, restrictive suit to waddle over to the bomb and stop it from exploding. Most of the time, he does something along the way to drive Sanborn crazy, as the sergeant does not agree with their higher-ups that James is some kind of inspired hellcat (the higher-ups, of course, are not in immediate danger of blowing up along with him). It's fair to say that the bulk of this 131 minute film consists of the pregnant wait in the time between the team identifying the bomb and James successfully defusing it; agonising minutes waiting for something awful to happen. These sequences are put together with absolutely impeccable craftsmanship; my only previous context for Bigelow's direction was the faintly awful K-19: The Widowmaker, which suggested very little good about her talents, but then here she had to go and make something to prove me all sorts of wrong. What's amazing about the many tense moments in The Hurt Locker is how few of the customary tricks used to generate tension: there are no urgent close-ups or pounding drums or rapid-fire cuts. The most shocking thing about the movie, really, is how much of it takes place in lingering medium shots. Only the slightly intrusive use of hand-held camera, its characteristic wobbliness insisting "REALISM!" while just coming off as stale, threatens to puncture the uncanny effectiveness of these moments.

We're right there with the characters: it's terrifying and we absolutely know that things are going to go wrong, but it's kind of thrilling and fun anyway. I could take or leave the extended "hunt through Baghdad at night" sequence near the end, demonstrating how James's experiences have started to unravel his mind; the protracted pauses when we're waiting for the "boom" have more than done explained what we needed to know.

And that's where the film starts to wander into its more awkward territory. The filmmakers, it seems, do not believe that they are very good at their jobs; that we intuitively understand what's going on from the impact on ourselves as viewers from those masterful bomb-defusing sequences. So they explain everything, in the most explicit detail you could imagine; starting with that very same epigraph, all the way to the penultimate scene. Basically, this is one of those movies that is extremely good whenever characters keep their mouths shut; when there's dialogue, it's usually heavy-handed and leading. A shame, because the more-than-able cast - especially Renner, who has cropped up here and there in various things, and whose face communicates everything we could ever hope to know about James - doesn't need Bigelow and Boal whispering in the audience's ear to get their characters across. It's frankly damned annoying, and turns what could have been a truly marvelous war picture into a kind of harangue, at times; moments of intensity punctuated by lectures. Does it make The Hurt Locker a failure? Lord no, but it does mean that at the very best, it's a qualified success.

Categories: mr. cheney's war, oscar's best picture, thrillers, war pictures