When the volcano blow

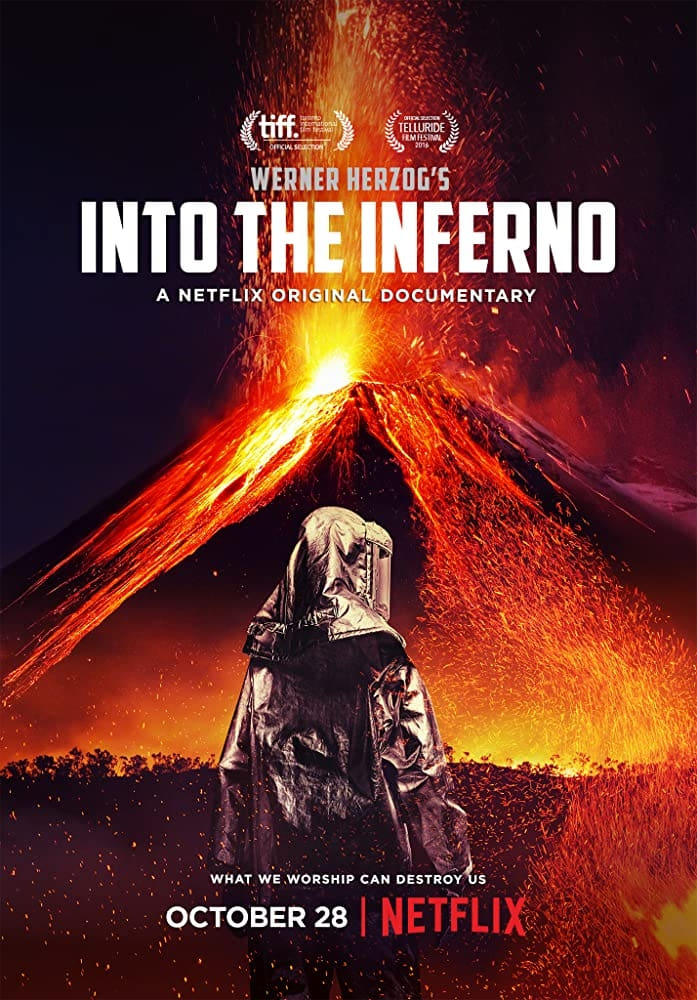

When all else fails, every Werner Herzog documentary has at least this going for it: they make for a fascinating glimpse into the things that Werner Herzog finds interesting, and he's nothing if not an interesting man himself. This is probably the best argument I can make in favor of all 104 minutes of the director's Into the Inferno, five wonderfully captivating documentaries that have been pressed together into one very weird shape. The best way to describe is it to imagine if sense of thematic dislocation that accompanies the albino alligator sequence of Herzog's Cave of Forgotten Dreams was spread across an entire feature film rather than carefully placed as the coda to a more unified piece. It's kind of maddening - maybe even it's even supposed to be maddening.

The unifying theme of the movie is, officially, the impact of volcanoes on human societies: several very different kinds of societies, and several different forms of impact. The less-official theme, but one which Herzog's choice of soundtrack (heavy on Christian liturgical chants) indicates that the director is fully anxious for us to note, is the nature of spiritual expression. Or at least the idea that volcanoes, such a powerful embodiment of the destructive capacity of the natural world and so otherworldly in their beauty, are inherently inclined towards providing we tiny human beings with spiritually meaningful experiences. Neither of those themes ends up actually covering all of the film's twists and turns, but let's hold that thought for just a moment.

Into the Inferno is a sequel, in the loosest sense, the sequel to two other Herzog documentaries*: the 1977 short La Soufrière, footage of which appears in the new film, and the 2007 Encounters at the End of the World, which has supplied some of its outtake footage. One of the titular encounters in the latter film was with volcanologist Clive Oppenheimer, stationed at the time in Antarctica, and the two men hit it off well enough to collaborate on this new project; the onscreen credits go so far to refer to Into the Inferno as "a film by" the both of them, though Herzog ends up with the sole directorial credit. The result is a film that travels across the Eastern Hemisphere from Indonesia and all the way back again, with stops in Australia, Ethiopia, and North Korea, and which only sometimes involves Oppenheimer and his insights into the physical nature of volcanoes.

That is, of course, the last thing Herzog cares about. As usual, his modus operandi is to seek out the most curious specimens of the human animal he can find in whatever extreme condition he arrives at along his travels, and Into the Inferno offers quite a splendid array: from the aboriginal shaman who claims that he can have literal one-on-one conversations with the volcano, which obligingly lights his cigarettes for him, to a Roman Catholic Indonesian earnestly building a bird-shaped shaped church, to a UC Berkeley paleoanthropologist whose thoughts on his field are delightfully low-stakes. Through each of these journeys, the backdrop is always some kind of volcano: one that has been dead since before the earliest flickering of human civilization, in the case of the Ethiopian hunt for prehistoric human remains, ones that are still pulsing with an unfathomable red glow in the case of the Indonesian volcanoes that bookend the movie. For all his fascination with humans and his own characteristically arch narration, Herzog never really does better than to step back and allow the volcanoes to speak for themselves, in the endlessly absorbing footage of bubbling magma and lava flows (some of it stock footage captured by fellow volcano experts Katia and Maurice Krafft, who died in a 1991 eruption), colors and shapes and fluidity that the human mind simply cannot quite accept as real all playing out under that soaring religious music, like you might find in a Terrence Malick movie, if Malick made movies about Hell instead of Heaven.

Honestly, it's always a little disappointing when Herzog cuts away from that footage, but he almost always cuts to something worth seeing: indigenous Indonesian children play-acting a sort of put-on exoticism for the German filmmaker's camera, obviously adoring the chance to play the ham; the rigid, graphically stunning procedure by which the diggers in Ethiopia ply their trade; and so on and so forth. It's all stitched together in the most ad hoc way you could imagine, but let us seriously ask the question: do we watch Werner Herzog films for their unyielding structural clarity? And while Into the Inferno is even looser and sloppier than most of his work (it is, in fact, the most free-wheeling and unstructured documentary of his that I've seen, allowing that I haven't yet seen his recent film about the internet, Lo and Behold, which I'm told works in much the same register), it forms a fairly uniform mood of reflection on the human drive towards spiritual systems.

Where things break is when the film heads into North Korea (the fourth of its five major movements). It's easy to figure out why it's supposed to fit - totalitarianism filling the role in one culture that religion fills in others - and there's even a volcano connection, though it's blatantly obvious that Herzog doesn't care. The material is, by itself, deeply fascinating, but it simply makes no sense for this to be the vessel in which it is delivered to the viewer. It's always more or less true throughout Into the Inferno that one wants more than Herzog gives us: more volcanoes, more indigenous children goofing around. But it's only in the North Korea segment that it seems like the director wants more, too: it's clear how much he wants to make a whole film about the way the country functions, which fascinates Herzog thanks to its ritualistic intensity far more than it appears to outrage him or alarm him or do any of the things that mention of North Korea typically does. And that movie would be great. But instead, we just get fragments, and once you've gotten through the North Korea sequence, it's hard to miss how much the rest of the film leading up to that point has been just as fragmentary. From there, it's hard not to feel a bit deflated by the whole of Into the Inferno: a movie in which every different piece is so intriguing that it becomes annoying that pieces are all we get. The whole movie ends up feeling a bit slack and superficial as a result. It's the summary of several different movies rather than a movie unto itself.

*And it has virtually the same title as his 2011 Into the Abyss, with which it has nothing else in common.

The unifying theme of the movie is, officially, the impact of volcanoes on human societies: several very different kinds of societies, and several different forms of impact. The less-official theme, but one which Herzog's choice of soundtrack (heavy on Christian liturgical chants) indicates that the director is fully anxious for us to note, is the nature of spiritual expression. Or at least the idea that volcanoes, such a powerful embodiment of the destructive capacity of the natural world and so otherworldly in their beauty, are inherently inclined towards providing we tiny human beings with spiritually meaningful experiences. Neither of those themes ends up actually covering all of the film's twists and turns, but let's hold that thought for just a moment.

Into the Inferno is a sequel, in the loosest sense, the sequel to two other Herzog documentaries*: the 1977 short La Soufrière, footage of which appears in the new film, and the 2007 Encounters at the End of the World, which has supplied some of its outtake footage. One of the titular encounters in the latter film was with volcanologist Clive Oppenheimer, stationed at the time in Antarctica, and the two men hit it off well enough to collaborate on this new project; the onscreen credits go so far to refer to Into the Inferno as "a film by" the both of them, though Herzog ends up with the sole directorial credit. The result is a film that travels across the Eastern Hemisphere from Indonesia and all the way back again, with stops in Australia, Ethiopia, and North Korea, and which only sometimes involves Oppenheimer and his insights into the physical nature of volcanoes.

That is, of course, the last thing Herzog cares about. As usual, his modus operandi is to seek out the most curious specimens of the human animal he can find in whatever extreme condition he arrives at along his travels, and Into the Inferno offers quite a splendid array: from the aboriginal shaman who claims that he can have literal one-on-one conversations with the volcano, which obligingly lights his cigarettes for him, to a Roman Catholic Indonesian earnestly building a bird-shaped shaped church, to a UC Berkeley paleoanthropologist whose thoughts on his field are delightfully low-stakes. Through each of these journeys, the backdrop is always some kind of volcano: one that has been dead since before the earliest flickering of human civilization, in the case of the Ethiopian hunt for prehistoric human remains, ones that are still pulsing with an unfathomable red glow in the case of the Indonesian volcanoes that bookend the movie. For all his fascination with humans and his own characteristically arch narration, Herzog never really does better than to step back and allow the volcanoes to speak for themselves, in the endlessly absorbing footage of bubbling magma and lava flows (some of it stock footage captured by fellow volcano experts Katia and Maurice Krafft, who died in a 1991 eruption), colors and shapes and fluidity that the human mind simply cannot quite accept as real all playing out under that soaring religious music, like you might find in a Terrence Malick movie, if Malick made movies about Hell instead of Heaven.

Honestly, it's always a little disappointing when Herzog cuts away from that footage, but he almost always cuts to something worth seeing: indigenous Indonesian children play-acting a sort of put-on exoticism for the German filmmaker's camera, obviously adoring the chance to play the ham; the rigid, graphically stunning procedure by which the diggers in Ethiopia ply their trade; and so on and so forth. It's all stitched together in the most ad hoc way you could imagine, but let us seriously ask the question: do we watch Werner Herzog films for their unyielding structural clarity? And while Into the Inferno is even looser and sloppier than most of his work (it is, in fact, the most free-wheeling and unstructured documentary of his that I've seen, allowing that I haven't yet seen his recent film about the internet, Lo and Behold, which I'm told works in much the same register), it forms a fairly uniform mood of reflection on the human drive towards spiritual systems.

Where things break is when the film heads into North Korea (the fourth of its five major movements). It's easy to figure out why it's supposed to fit - totalitarianism filling the role in one culture that religion fills in others - and there's even a volcano connection, though it's blatantly obvious that Herzog doesn't care. The material is, by itself, deeply fascinating, but it simply makes no sense for this to be the vessel in which it is delivered to the viewer. It's always more or less true throughout Into the Inferno that one wants more than Herzog gives us: more volcanoes, more indigenous children goofing around. But it's only in the North Korea segment that it seems like the director wants more, too: it's clear how much he wants to make a whole film about the way the country functions, which fascinates Herzog thanks to its ritualistic intensity far more than it appears to outrage him or alarm him or do any of the things that mention of North Korea typically does. And that movie would be great. But instead, we just get fragments, and once you've gotten through the North Korea sequence, it's hard to miss how much the rest of the film leading up to that point has been just as fragmentary. From there, it's hard not to feel a bit deflated by the whole of Into the Inferno: a movie in which every different piece is so intriguing that it becomes annoying that pieces are all we get. The whole movie ends up feeling a bit slack and superficial as a result. It's the summary of several different movies rather than a movie unto itself.

*And it has virtually the same title as his 2011 Into the Abyss, with which it has nothing else in common.