Mine eyes have seen the gloury

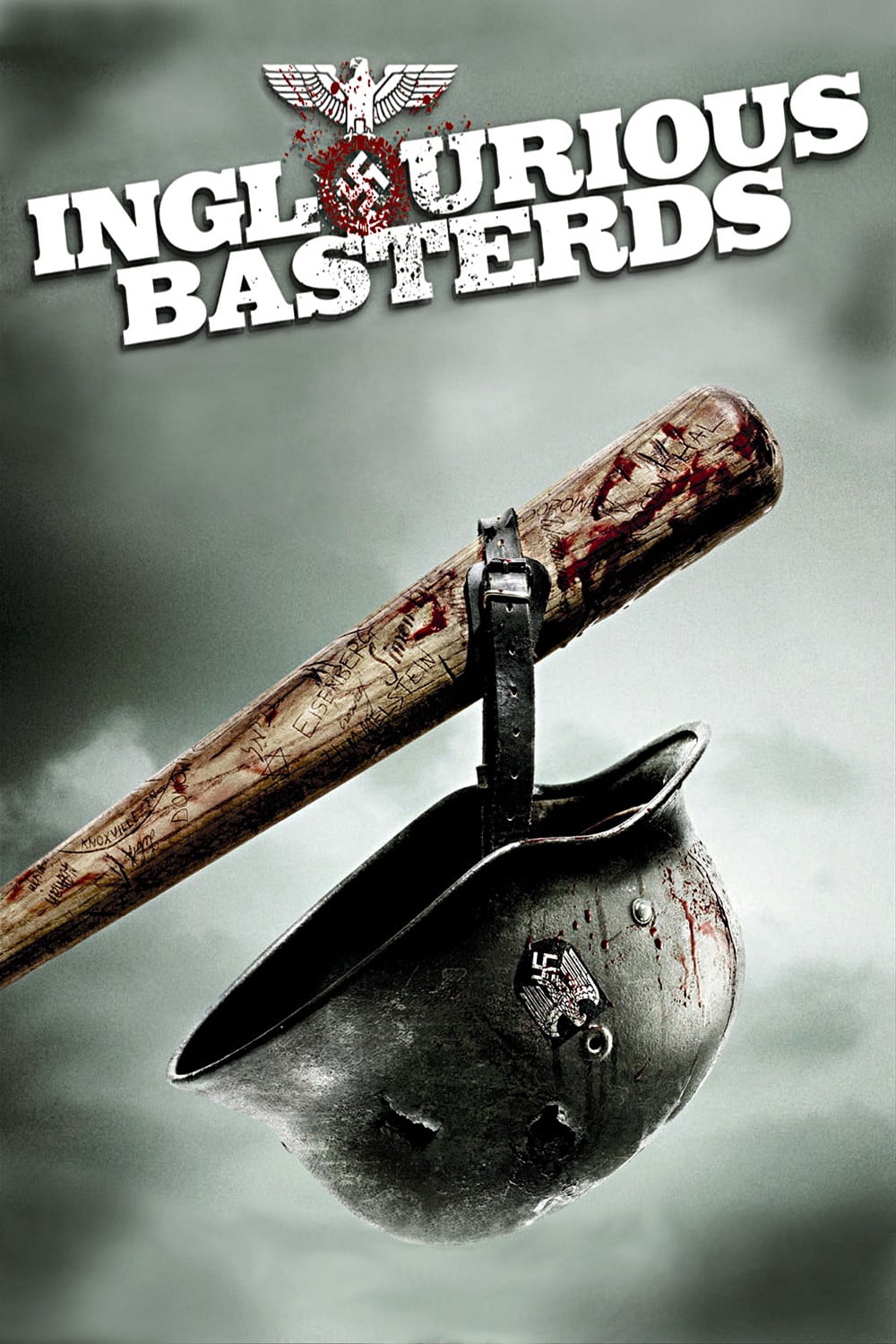

Inglourious Basterds is a marvel, at least. Like it or hate it or worship it, I'm pretty sure that you've never seen anything like it. I know, because I have seen many films just like it, and I still haven't seen anything like it. But that's what makes Quentin Tarantino the man he is: there's not a single new idea in any of his films, but something about the way he puts them all together is bracing and original. He is a singular talent: the cinema's reigning lord of pop culture post-modernism. And he's just released the most challenging and intellectually engaging film of his deceptively intelligent career.

Since you don't live under a rock, you know that the film is about a team of Jewish American soldiers united under the command of a good ol' boy with some Apache blood in him, Aldo Raine (Brad Pitt), and what these soldiers do is stalk through the forests and fields of World War II France and kill the shit out of Nazis. There's a good chance that you also know that the film really isn't about the Basterds much at all; nor is it about any one person or group. The original, Sergio Leone-dusted working title for the film was Once Upon a Time in Nazi-Occupied France, and that's pretty much the perfect description of the film's content; a whole lot of stuff happening in France in 1944 (and a little bit in 1941).

Honestly, there's simply way too much going on here for me to even pretend that I can grapple with all of it in one review based upon one viewing. It is for good or not a quintessential Tarantino movie: it looks so damn simple at first, but the more you sit and think, the more it becomes obvious that it's lousy with nested layers of meaning. Which doesn't alleviate the very strong suspicion that Tarantino himself might have had no idea what the hell was going on; he's either one of the most self-ignorant filmmakers in modern cinema, or he is freakishly good at misrepresenting himself as a bit of a yahoo in interviews. I have no damn idea. But just like Pulp Fiction is much more than just a fun, structurally audacious mobster flick and Kill Bill is more than a compendium of tropes from '70s genre flicks, so is Inglourious Basterds much more than a supremely gory revenge tale of Jews turning the tables on the the Nazis. Though it certainly is that.

What it really is, as most everybody who wasn't too disgusted to give the film a chance has already mentioned, is a movie about movies about WWII. Specifically, it is Tarantino's version of a 1970s Italian war film, a highly robust subset of Italian film; other than making films about cannibals and nude women (there are two ways to read that clause, and they're both accurate), there's nothing '70s Italian B-directors enjoyed more than spinning yarns about the terrible things the Germans did in the war. One such film was Quel maladetto treno blindato, literally "The Cursed Armored Train", but the commonest English release title is The Inglorious Bastards. There are exactly no points of narrative similarity between Tarantino's film and the Italian original, but I'm guessing that wasn't a big concern; he's just trying to make it as easy as possible for us to take note of what he's doing.

One of the main things that's happening in Inglourious Basterds - if there is a grand unifying theory of everything in the film, I cannot come up with it - is a commentary on representation in war films. On a certain level of abstraction, everything we're looking at is a broad parody of the tropes of other movies. This is most obvious in the single scene set in the British command offices: General Ed Fenech (Mike Myers, a Canadian) and Lt. Archie Hicox (Michael Fassbender, a German) play two of the most ridiculously plummy fake Brits you will ever see, yammering on about mixing drinks and I say old chap and Good Show, and the like. It's goofy as hell, and completely freaking hilarious if you've seen the old wartime films made in England where everybody actually does act that way. The Basterds themselves are a parody of the gung-ho, can't-fail American squad of awesomely competent G.I. Joes. And the mighty amounts of blood and torture are nothing so much as the natural extension of the ultra-violent Italian war movies, with the budget and technology to make the blood and prosthetics look even that much more realistic.

Of course, Inglourious Basterds is a relentlessly fictional film - the lies it tells are truly epic in scope. By extension, Tarantino is at least suggesting that all war movies are lies to the same degree; they might not tell such easily disprovable falsehoods, but that's a matter of degree. A direct riposte to the predictable howls of outrage from people wondering when the hell Tarantino is going to grow up and start addressing the real world, anyway, the film as much as argues, "what movie was ever about the real world? And with that in mind, why can't I just go balls-out crazy?" Besides, he already demonstrated in Pulp Fiction that movies and television have replaced the real world as our model for reality; to call something "real" actually means that it's reminiscent of "realist" films.

Forgive this abrupt jump, but I really can't think of a segue: the construction of Inglourious Basterds is where things get really interesting. Like Kill Bill, it's divided into chapters, although they are mostly chronologically straightforward; and each of these chapters is tonally different. For my tastes, the best are the first and fourth, with a special nod to the fifth. The first especially is the sequence that we're all going to remember twenty years from now: a real-time 15 or 20-minute conversation between S.S. Col. Hans Landa (Christoph Waltz, who gives a truly exemplary performance, one of the best Tarantino has ever directed) and a dairy farmer named Perrier LaPadite (Denis Menochet). The talk starts out on the most banal pleasantries, turns to Nazi business, returns to banality, and then Landa suddenly asks LaPadite to give up the Jewish refugees hiding in his floorboards, because it will be much easier for everyone that way. This is an absolutely immaculate sequence: every cut and every shot works together like the instruments in an orchestra, building, building, building the tension, stretching out the pregnant terror of the moment until the audience is ready to burst.

The third chapter sees that and raises it with a mind-blowing scene set in a bar, where the Basterds are meant to be meeting a German double agent (Diane Kruger), only to find themselves stymied by an unexpected party and an even less-expected S.S. officer. This is the make-or-break point for the film, I suspect; an endless scene of people chattering, playing games, discussing the sociology of King Kong - it has to be a solid half-hour or longer, and it is either mesmerising or atrociously boring. Taste is a wicked hellcat like that.

Everything is filled with freewheeling, uncontrolled ambition like that: the fifth chapter opens on the strains of David Bowie's "Cat People (Putting Out Fire)" that could not possibly be better; the film barely has an hour of plot even with two completely separate story arcs, one involving a young French Jew (Mélanie Laurent) who never meets the Basterds and has her own plan for vengeance, and yet it stretches to more than double that length. We could argue whether Tarantino has any right to do these things, but let's at least agree that he doesn't want for self-confidence. And that's what Inglourious Basterds is to me: a film made by a man who knows why he makes every single choice, even if it's desperately unintuitive. This is filmmaking at its bravest, and whether Tarantino is a genius or a fool, he does nothing by accident.

Since you don't live under a rock, you know that the film is about a team of Jewish American soldiers united under the command of a good ol' boy with some Apache blood in him, Aldo Raine (Brad Pitt), and what these soldiers do is stalk through the forests and fields of World War II France and kill the shit out of Nazis. There's a good chance that you also know that the film really isn't about the Basterds much at all; nor is it about any one person or group. The original, Sergio Leone-dusted working title for the film was Once Upon a Time in Nazi-Occupied France, and that's pretty much the perfect description of the film's content; a whole lot of stuff happening in France in 1944 (and a little bit in 1941).

Honestly, there's simply way too much going on here for me to even pretend that I can grapple with all of it in one review based upon one viewing. It is for good or not a quintessential Tarantino movie: it looks so damn simple at first, but the more you sit and think, the more it becomes obvious that it's lousy with nested layers of meaning. Which doesn't alleviate the very strong suspicion that Tarantino himself might have had no idea what the hell was going on; he's either one of the most self-ignorant filmmakers in modern cinema, or he is freakishly good at misrepresenting himself as a bit of a yahoo in interviews. I have no damn idea. But just like Pulp Fiction is much more than just a fun, structurally audacious mobster flick and Kill Bill is more than a compendium of tropes from '70s genre flicks, so is Inglourious Basterds much more than a supremely gory revenge tale of Jews turning the tables on the the Nazis. Though it certainly is that.

What it really is, as most everybody who wasn't too disgusted to give the film a chance has already mentioned, is a movie about movies about WWII. Specifically, it is Tarantino's version of a 1970s Italian war film, a highly robust subset of Italian film; other than making films about cannibals and nude women (there are two ways to read that clause, and they're both accurate), there's nothing '70s Italian B-directors enjoyed more than spinning yarns about the terrible things the Germans did in the war. One such film was Quel maladetto treno blindato, literally "The Cursed Armored Train", but the commonest English release title is The Inglorious Bastards. There are exactly no points of narrative similarity between Tarantino's film and the Italian original, but I'm guessing that wasn't a big concern; he's just trying to make it as easy as possible for us to take note of what he's doing.

One of the main things that's happening in Inglourious Basterds - if there is a grand unifying theory of everything in the film, I cannot come up with it - is a commentary on representation in war films. On a certain level of abstraction, everything we're looking at is a broad parody of the tropes of other movies. This is most obvious in the single scene set in the British command offices: General Ed Fenech (Mike Myers, a Canadian) and Lt. Archie Hicox (Michael Fassbender, a German) play two of the most ridiculously plummy fake Brits you will ever see, yammering on about mixing drinks and I say old chap and Good Show, and the like. It's goofy as hell, and completely freaking hilarious if you've seen the old wartime films made in England where everybody actually does act that way. The Basterds themselves are a parody of the gung-ho, can't-fail American squad of awesomely competent G.I. Joes. And the mighty amounts of blood and torture are nothing so much as the natural extension of the ultra-violent Italian war movies, with the budget and technology to make the blood and prosthetics look even that much more realistic.

Of course, Inglourious Basterds is a relentlessly fictional film - the lies it tells are truly epic in scope. By extension, Tarantino is at least suggesting that all war movies are lies to the same degree; they might not tell such easily disprovable falsehoods, but that's a matter of degree. A direct riposte to the predictable howls of outrage from people wondering when the hell Tarantino is going to grow up and start addressing the real world, anyway, the film as much as argues, "what movie was ever about the real world? And with that in mind, why can't I just go balls-out crazy?" Besides, he already demonstrated in Pulp Fiction that movies and television have replaced the real world as our model for reality; to call something "real" actually means that it's reminiscent of "realist" films.

Forgive this abrupt jump, but I really can't think of a segue: the construction of Inglourious Basterds is where things get really interesting. Like Kill Bill, it's divided into chapters, although they are mostly chronologically straightforward; and each of these chapters is tonally different. For my tastes, the best are the first and fourth, with a special nod to the fifth. The first especially is the sequence that we're all going to remember twenty years from now: a real-time 15 or 20-minute conversation between S.S. Col. Hans Landa (Christoph Waltz, who gives a truly exemplary performance, one of the best Tarantino has ever directed) and a dairy farmer named Perrier LaPadite (Denis Menochet). The talk starts out on the most banal pleasantries, turns to Nazi business, returns to banality, and then Landa suddenly asks LaPadite to give up the Jewish refugees hiding in his floorboards, because it will be much easier for everyone that way. This is an absolutely immaculate sequence: every cut and every shot works together like the instruments in an orchestra, building, building, building the tension, stretching out the pregnant terror of the moment until the audience is ready to burst.

The third chapter sees that and raises it with a mind-blowing scene set in a bar, where the Basterds are meant to be meeting a German double agent (Diane Kruger), only to find themselves stymied by an unexpected party and an even less-expected S.S. officer. This is the make-or-break point for the film, I suspect; an endless scene of people chattering, playing games, discussing the sociology of King Kong - it has to be a solid half-hour or longer, and it is either mesmerising or atrociously boring. Taste is a wicked hellcat like that.

Everything is filled with freewheeling, uncontrolled ambition like that: the fifth chapter opens on the strains of David Bowie's "Cat People (Putting Out Fire)" that could not possibly be better; the film barely has an hour of plot even with two completely separate story arcs, one involving a young French Jew (Mélanie Laurent) who never meets the Basterds and has her own plan for vengeance, and yet it stretches to more than double that length. We could argue whether Tarantino has any right to do these things, but let's at least agree that he doesn't want for self-confidence. And that's what Inglourious Basterds is to me: a film made by a man who knows why he makes every single choice, even if it's desperately unintuitive. This is filmmaking at its bravest, and whether Tarantino is a genius or a fool, he does nothing by accident.

Categories: movies about wwii, quentin tarantino, violence and gore, war pictures