College days

Previously reviewed at the Film Experience

Many directors have had great years, in which they've released two (or more!) tremendously good films that demonstrate the breadth of their skills. But very, very few directors have ever had a years like Yuasa Masaaki had in 2017. This was the year that the animation genius, whose work has been almost entirely in television, finally released his second and third features, 13 years after the tremendous Mind Game in 2004. Somehow, both of them leaped over that already extremely high bar, giving Yuasa a year that wasn't merely "tremendously good", but managed to completely redefined what the animation medium was capable of. The latter of these by about a month, Lu Over the Wall, was the first released in the United States, and it's a complete marvel: a fun, energetic fairy tale challenging all the accepted rules of how 2-D character animation can be achieved in a digital workflow, and a lovely musical adventure on top of it. It's also a thin achievement indeed compared to Night Is Short, Walk On Girl, one of the most astonishing pieces of animation made in the 21st Century, a marriage of style, narrative, theme, and mood that feels almost entirely without precedent.

I hedge with that "almost", and offer my one mild disappointment in the film, because there exists an 11-part TV series from 2010, The Tatami Galaxy, that pioneered all of the basics of style and narrative developed into maturity in Night Is Short. That series, also directed by Yuasa and, like Night Is Short, adapted from a novel by Morimi Tomohiko, tells of the parallel universe adventures of a nameless boy whose college career keeps developing in wildly different ways in every different timeline, but always somehow ending in romantic frustration. The feature isn't exactly a sequel, though it borrows many characters and character designs, and the basic psychological state. Now we have two nameless college protagonists, a male senior (Hoshino Gen) and a female junior (Hanazawa Kana); he has a huge crush on her and goes about trying to passive-aggressively communicate this to her in the most idiotic ways, while she quite blithely notices none of this, and wanders throughout Kyoto having the time of her life making extremely bad decisions around drinking and the sorts of dubious people she spends time with.

The character types are the spine of the film, but not really the point. Instead, this is a celebration of the freedom of youth, told from an amused, wise, older perspective that recognises that both characters are probably complete idiots, but young enough and resilient enough that they'll certainly survive just fine, and wasn't it absolutely great when we could all say the same about ourselves? The plot- but it doesn't do to call it a plot. It's a chain of events, tied together with a tight chain of causality (the clarity of the causal links turns out, in fact, to be a critical aspect of the climax), but feeling like an unpredictable sprawl that cannot possibly be contained in the film's 92 minutes, nor in the short night promised by the title. And it explicitly is all set during one night, though a night that somehow manages to stretch from early summer to late fall. Realism is not remotely a concern here; the goal, I think, is to create an intoxicating subjectivity, the feeling of being a young adult free to spend the night wandering around the city discovering life and finding that every night is both more or less the same and a brand new experience of all the weird and wild things life has to offer.

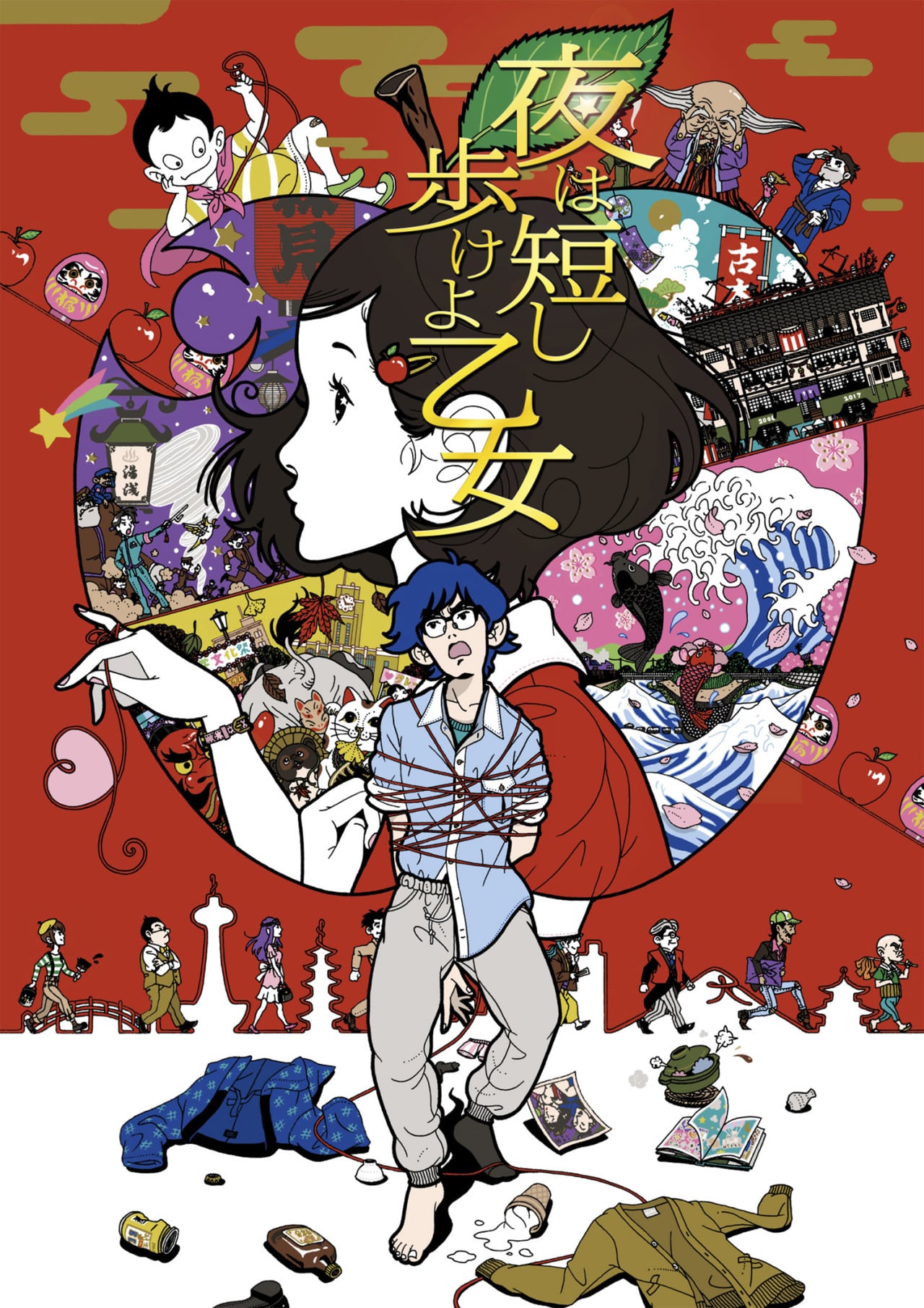

It would not do to belabor Ueda Makoto's script any more than that; the peculiar feeling of Night Is Short is that it has hardly been written at all, but keeps finding its path as it topples forward. This sense of boundlessness is amplified by the film's style, which is really quite entirely unlike anything else I've ever seen, other than The Tatami Galaxy. And even then, Night Is Short represents an exaggeration and expansion upon that show's aesthetic, which was already pretty exaggerated to begin with. Trying to describe the film's look in prose is a fool's errand, but if I was going to make a stab at it, I'd start by suggestion that the characters all feel like line drawings, round empty shapes with only the bare minimum of detail to clearly define their faces and richly saturated clothes. Their skin is colored white, except when they are sick or drunk (both of which happen frequently) and turn magenta; their bodies are like the caricatures out of a comic strip, with elongated, distorted features that distort even more in moments of stress or enthusiasm. The boy's entire body contorts into a large comma-shaped curve when he's petrified by his humiliated libido; the girl is generally more normal, but she can still squash herself into impossible shapes, at one pointing leading a line dance in which she trusts her arms in huge, wobbly arcs, right at the camera, her hand grossly exploding in size as it moves. It hardly needs mentioning that the physical world is just as malleable as the characters: shifting colors and even apparent locations as needed to evoke the subjective experience of the characters, creating an impossible environment of places that fit together only occasionally, and with the free anti-physicality of dreaming.

It's an aesthetic that constantly reinvents itself, just as much as the story does, and as the characters can't help but do. The film feels inexhaustible. Stylistically, it never settles down, including flashbacks that are even more starkly, colorfully minimalist than the rest of the movie, often including just basic shapes that evoke characters rather than portray them. Narratively, it moves from rat-a-tat banter to elaborate slapstick setpieces to complicated hyper-narrative touches. And along the way, it stops for long enough to have a ten-minute musical sequence in which a guerilla play is interrupted by one lead actor declaring his love who is interrupted by a different actor declaring his love. The film feels like it understands no rules or limitations, and yet it never feels arbitrary or too much for the sake of muchness; perhaps the weirdest thing is that every new scene feels inevitable, just like very stylistic flourish seems to be the only possible way the film could have developed its characters and their messy emotions. It's everything, a movie about the bottomless energy of youth that itself possesses that energy and instills it in the viewer, and in a great year for animation, it's still pretty effortlessly one of the pinnacle achievements in any incarnation of that medium.

Many directors have had great years, in which they've released two (or more!) tremendously good films that demonstrate the breadth of their skills. But very, very few directors have ever had a years like Yuasa Masaaki had in 2017. This was the year that the animation genius, whose work has been almost entirely in television, finally released his second and third features, 13 years after the tremendous Mind Game in 2004. Somehow, both of them leaped over that already extremely high bar, giving Yuasa a year that wasn't merely "tremendously good", but managed to completely redefined what the animation medium was capable of. The latter of these by about a month, Lu Over the Wall, was the first released in the United States, and it's a complete marvel: a fun, energetic fairy tale challenging all the accepted rules of how 2-D character animation can be achieved in a digital workflow, and a lovely musical adventure on top of it. It's also a thin achievement indeed compared to Night Is Short, Walk On Girl, one of the most astonishing pieces of animation made in the 21st Century, a marriage of style, narrative, theme, and mood that feels almost entirely without precedent.

I hedge with that "almost", and offer my one mild disappointment in the film, because there exists an 11-part TV series from 2010, The Tatami Galaxy, that pioneered all of the basics of style and narrative developed into maturity in Night Is Short. That series, also directed by Yuasa and, like Night Is Short, adapted from a novel by Morimi Tomohiko, tells of the parallel universe adventures of a nameless boy whose college career keeps developing in wildly different ways in every different timeline, but always somehow ending in romantic frustration. The feature isn't exactly a sequel, though it borrows many characters and character designs, and the basic psychological state. Now we have two nameless college protagonists, a male senior (Hoshino Gen) and a female junior (Hanazawa Kana); he has a huge crush on her and goes about trying to passive-aggressively communicate this to her in the most idiotic ways, while she quite blithely notices none of this, and wanders throughout Kyoto having the time of her life making extremely bad decisions around drinking and the sorts of dubious people she spends time with.

The character types are the spine of the film, but not really the point. Instead, this is a celebration of the freedom of youth, told from an amused, wise, older perspective that recognises that both characters are probably complete idiots, but young enough and resilient enough that they'll certainly survive just fine, and wasn't it absolutely great when we could all say the same about ourselves? The plot- but it doesn't do to call it a plot. It's a chain of events, tied together with a tight chain of causality (the clarity of the causal links turns out, in fact, to be a critical aspect of the climax), but feeling like an unpredictable sprawl that cannot possibly be contained in the film's 92 minutes, nor in the short night promised by the title. And it explicitly is all set during one night, though a night that somehow manages to stretch from early summer to late fall. Realism is not remotely a concern here; the goal, I think, is to create an intoxicating subjectivity, the feeling of being a young adult free to spend the night wandering around the city discovering life and finding that every night is both more or less the same and a brand new experience of all the weird and wild things life has to offer.

It would not do to belabor Ueda Makoto's script any more than that; the peculiar feeling of Night Is Short is that it has hardly been written at all, but keeps finding its path as it topples forward. This sense of boundlessness is amplified by the film's style, which is really quite entirely unlike anything else I've ever seen, other than The Tatami Galaxy. And even then, Night Is Short represents an exaggeration and expansion upon that show's aesthetic, which was already pretty exaggerated to begin with. Trying to describe the film's look in prose is a fool's errand, but if I was going to make a stab at it, I'd start by suggestion that the characters all feel like line drawings, round empty shapes with only the bare minimum of detail to clearly define their faces and richly saturated clothes. Their skin is colored white, except when they are sick or drunk (both of which happen frequently) and turn magenta; their bodies are like the caricatures out of a comic strip, with elongated, distorted features that distort even more in moments of stress or enthusiasm. The boy's entire body contorts into a large comma-shaped curve when he's petrified by his humiliated libido; the girl is generally more normal, but she can still squash herself into impossible shapes, at one pointing leading a line dance in which she trusts her arms in huge, wobbly arcs, right at the camera, her hand grossly exploding in size as it moves. It hardly needs mentioning that the physical world is just as malleable as the characters: shifting colors and even apparent locations as needed to evoke the subjective experience of the characters, creating an impossible environment of places that fit together only occasionally, and with the free anti-physicality of dreaming.

It's an aesthetic that constantly reinvents itself, just as much as the story does, and as the characters can't help but do. The film feels inexhaustible. Stylistically, it never settles down, including flashbacks that are even more starkly, colorfully minimalist than the rest of the movie, often including just basic shapes that evoke characters rather than portray them. Narratively, it moves from rat-a-tat banter to elaborate slapstick setpieces to complicated hyper-narrative touches. And along the way, it stops for long enough to have a ten-minute musical sequence in which a guerilla play is interrupted by one lead actor declaring his love who is interrupted by a different actor declaring his love. The film feels like it understands no rules or limitations, and yet it never feels arbitrary or too much for the sake of muchness; perhaps the weirdest thing is that every new scene feels inevitable, just like very stylistic flourish seems to be the only possible way the film could have developed its characters and their messy emotions. It's everything, a movie about the bottomless energy of youth that itself possesses that energy and instills it in the viewer, and in a great year for animation, it's still pretty effortlessly one of the pinnacle achievements in any incarnation of that medium.

Categories: adventure, animation, best of the 10s, japanese cinema, love stories, teen movies, top 10, yuasa masaaki