Universal Horror: Children of the night

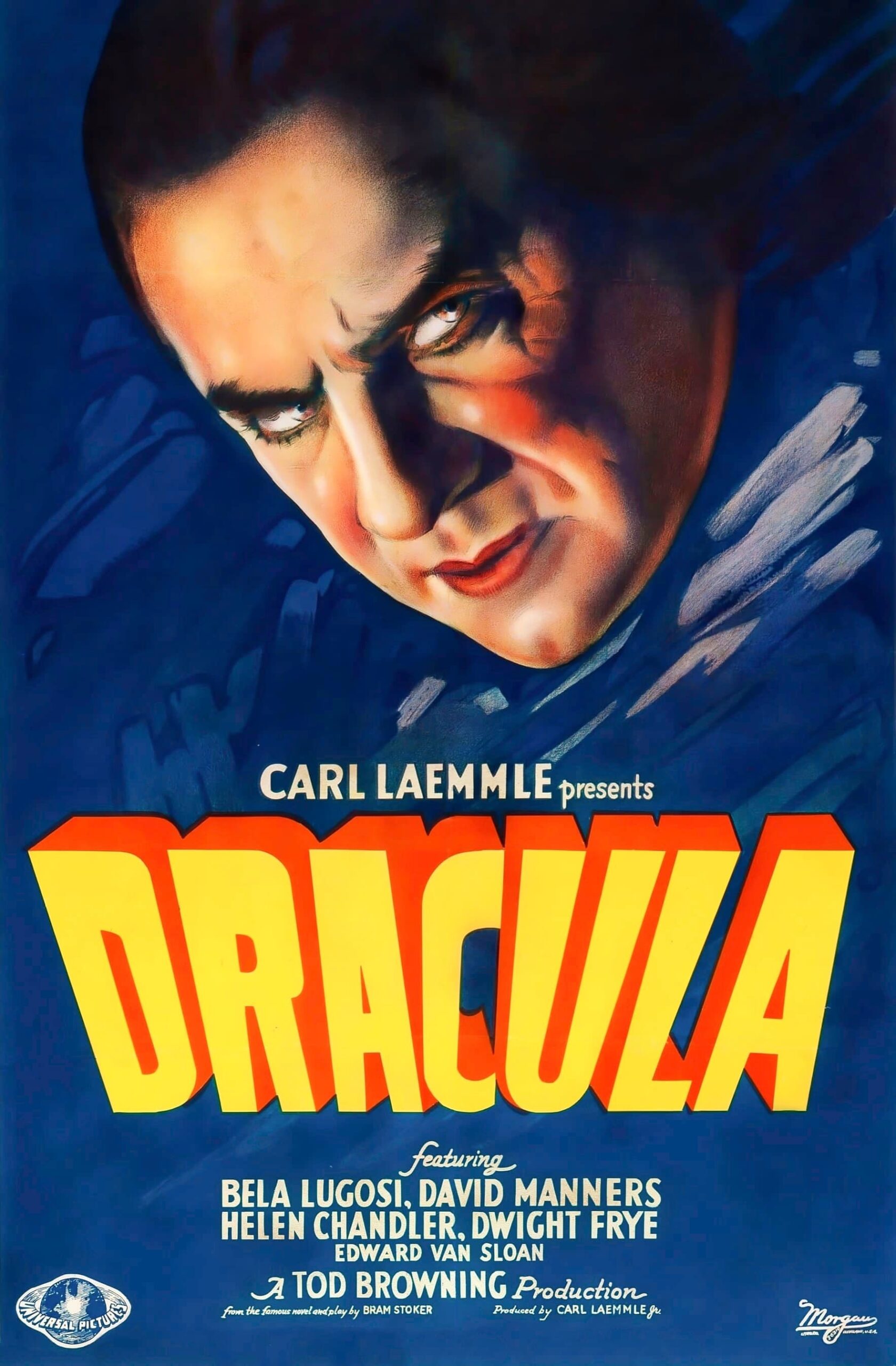

The 1931 adaptation of Dracula is a classic if ever a film has deserved that name: an incalculably important film, just about every single horror picture made in the last 78 years - and certainly, every vampire picture - owes it some debt, if only a small one. Its influence has extended far beyond even the movies; if your mental image of a vampire is a pale man with black hair in a cape purring, "I vant to sahk your blahd", then you too have been touched by this, unarguably one of the most influential American movies of the 1930s, possibly ever.

It is an unfortunate twist in the story that Dracula is also kind of bad.

But before I get to that, let's have a wee tiny history lesson: the American horror film, as a genre, didn't really exist in the silent era. There were isolated examples, without a doubt; but censorship issues and public tastes kept the form from developing into anything even vaguely resembling the current environment we enjoy (or fail to enjoy) today. No, the only people making horror films in any kind of systematic way back then were the Germans, and the famous Expressionist horror of Weimar remains to this very day one of the most visually distinctive styles in the history of the art form.

Now, it just so happened that the president of Universal Pictures, a certain Carl Laemmle, Sr., had been giving some thought to adapting Bram Stoker's beloved potboiler Dracula for a number of years, not because he particularly liked the material (he famously hated it), but because his extremely savvy son Carl Laemmle, Jr. seemed to think that the book was just itching to become a blockbuster. The time for this adaptation finally seemed right late in the 1920s, when disaster struck - not just for the Laemmles, but for the whole damn country. The Great Depression meant that the globe-trotting epic adaptation of the novel that Universal was gearing up to make was absolutely out of the question, but a solution was easily found: the 1924 stage adaptation by Hamilton Deane, which was anyway the version of the story most people were familiar with, could be readily turned into something far cheaper than Stoker's original text, being set almost exclusively in a single London house. In a nod to the more expansive representational powers of the cinema, the book's Transylvanian opening sequence was restored, but the rest was taken straight from Deane, including his compression of the plot and characters - not that any film version of Dracula has ever done much in the way of honoring Stoker's original plot and characters.

The film starred two members of the Broadway run of Deane's play, Bela Lugosi and Edward Van Sloan, and became a stupidly large hit - the most profitable movie Universal released during the Depression. Its influence was quick and certain: as the first American horror movie to explicitly ground its narrative in the supernatural, it opened up a whole new world of storytelling possibilities. It turned Universal overnight into a horror film factory, permitting the creation of the masterful Frankenstein later in the same year. And - I cannot stress this point enough - it was also kind of bad.

Dracula, though directed by Tod Browning, a more than capable filmmaker in the genre, and shot by the amazing Karl Freund, one of the best German cinematographers of the 1920s (making him arguably one of the best cinematographers in history, although he got very few chances to do anything worthwhile after this film), is a perfect example of the worst traits of Hollywood films in the early sound era. A combination of problems, beginning with its budgetary issues and the elder Laemmle's dubious feelings towards the project, and continuing to Browning's alcoholism and outsized grief for the recently deceased Lon Chaney, Sr. left the production in a rocky place (allegedly, it also left Freund to direct most of the London scenes himself, without the benefit of speaking English), and the result is that the bulk of the film, as much as the last two-thirds, feels exactly like what happens when you put a film camera on a theatrical stage to record a live play. Considering that this is frequently cited as the film linking German horror cinema with American horror cinema (a marriage still thriving today), it is peculiar and frustrating that the adjective which best describes it is "uncinematic".

And this much must be said: it's not all that way. The opening 24 minutes, or thereabouts (the film runs for 74), are close to perfection. This is the part of the film concerning the English solicitor Renfield (Dwight Frye) in Transylvania, visiting to deliver some paperwork to the reclusive Count Dracula (Lugosi, but you didn't need me to point that out). It is also a wholly effective immersion in gloomy design and gloomier lighting, creating a mood of suffocating foreboding that's as good as any of its Germanic ancestors. If the whole movie looked as good and as creepy (yes, creepy, even after decades of films have had the chance to improve on it) as the opening, up to the shot of a vampire-crazy Renfield staring out of the hold of a ship with terrifying bug eyes, it would more than deserve its reputation and its place in history.

But 'tis not to be. Almost from the moment that Dracula exits the ship and walks into the Royal Albert Hall, Dracula becomes a crushing bore, not just visually uninspired, but crippled with a barely functional screenplay. Nearly all of the film takes place in the home of Dr. Seward (Herbert Bunston), a pleasant manor on the grounds of his sanitarium, next door to Carfax Abbey, where Dracula has set up his new home, and for a solid 40 minutes, exactly nothing happens.

The characters, loosely adapted from Stoker, include Seward's daughter Mina (Helen Chandler), her fiancé John Harker (David Manners), and her good friend Lucy Weston (Frances Dade). We needn't worry much about Lucy, though, since she falls for Dracula pretty quickly, and becomes his newest vampire bride almost as quickly, and after that she's out of the movie, except for a single shot. Her death is brought to the attention of Prof. Abraham Van Helsing (Edward Van Sloan), a scientist who believes in the occult, insofar as he expects that one day, science will be able to rationally explain all manner of things that go bump in the night.

When I said that nothing happens? I lied. One thing actually does happen, and happen, and happen, and happen. Basically, all the good characters will be sitting around in Seward's parlor, and Dracula will poke his head in and be charming and somehow threatening, Van Helsing will furrow his brow, and declare that the must stop this vampire in their midst. They do not, Mina is attacked offscreen during the night, rinse, repeat. It is as stultifying as any other early-'30s stage adaptation, and if you've seen more than a couple you know just how stultifying that can be. This would be sufficient by itself to earn the movie a thick black mark, except that I haven't mentioned the major plothole concerning Lucy, who dies, is mentioned casually as having become a vampire a good 20 minutes later, and who thereafter ceases to be heard from ever again. Nor the editing of the final scene, which makes time flow like a corkscrew and ends with a truly inexplicable little moment of Van Helsing having to do one more thing, except he doesn't do it and we don't know what it is. There's also the question of how it is that Renfield manages to keep escaping from his cell in the sanitarium to wander around Seward's house, or indeed what possible use he can be to Dracula, since all he does is look crazy and then at the very end explode in a geyser of exposition. And God, let me not even remember the horrible comic relief nurse (Joan Standing) and security guard (Charles Gerrard).

Through all this endless slog of bad writing and flat staging, only three men are able to keep Dracula from sinking into absolute worthlessness: Lugosi, Van Sloan, and Frye. Bela Lugosi's performance as Dracula is, of course, not even worth my description: it's virtually unimaginable that anyone has completely avoided it, and while he was never anywhere near as good an actor as e.g. Lon Chaney or Boris Karloff, when he got to chew hisself a nice thick chunk of scenery, he was absolutely a treat to watch (and of course, the Dracula screenplay gives him plenty to chew on: "Children ahf the night... what music dey make"; "I never... drink... wine"; et cetera ad infinitum). Van Sloan's German accent is very nearly as cartoonish as Lugosi's Hungarian, except that he doesn't come by it honestly, and while the performance is undeniably campy, it's a lot of fun, especially during the late scene when Dracula and Van Helsing face off in one of the all-time great ham festivals of the 1930s. Not to miss out on the fun, Frye gives a completely unhinged performance that ranges from absurdly melodramatic to genuinely disturbing in the space of a few lines, even a syllable - he's always reminded me a little bit of Dudley Manlove in a far different Lugosi vehicle, Plan 9 from Outer Space, only with a dangerous edge that makes his flouncy excesses seem less funny and more terrifying.

But outside of that core - and the uncanny atmosphere of the opening - there's precious little to like about Dracula. Nothing I can do would make the least dent in its historic position - rightfully so, and I do not wish to take away its awesome influence - but there are very few films I can name for which the sniffy phrase "of historical interest only" has been more dreadfully accurate.

Reviews in this series

Dracula (Browning, 1931)

Drácula (Melford, 1931)

Dracula's Daughter (Hillyer, 1936)

Son of Dracula (Siodmak, 1943)

House of Frankenstein (Kenton, 1944)

House of Dracula (Kenton, 1945)

Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein (Barton, 1948)

It is an unfortunate twist in the story that Dracula is also kind of bad.

But before I get to that, let's have a wee tiny history lesson: the American horror film, as a genre, didn't really exist in the silent era. There were isolated examples, without a doubt; but censorship issues and public tastes kept the form from developing into anything even vaguely resembling the current environment we enjoy (or fail to enjoy) today. No, the only people making horror films in any kind of systematic way back then were the Germans, and the famous Expressionist horror of Weimar remains to this very day one of the most visually distinctive styles in the history of the art form.

Now, it just so happened that the president of Universal Pictures, a certain Carl Laemmle, Sr., had been giving some thought to adapting Bram Stoker's beloved potboiler Dracula for a number of years, not because he particularly liked the material (he famously hated it), but because his extremely savvy son Carl Laemmle, Jr. seemed to think that the book was just itching to become a blockbuster. The time for this adaptation finally seemed right late in the 1920s, when disaster struck - not just for the Laemmles, but for the whole damn country. The Great Depression meant that the globe-trotting epic adaptation of the novel that Universal was gearing up to make was absolutely out of the question, but a solution was easily found: the 1924 stage adaptation by Hamilton Deane, which was anyway the version of the story most people were familiar with, could be readily turned into something far cheaper than Stoker's original text, being set almost exclusively in a single London house. In a nod to the more expansive representational powers of the cinema, the book's Transylvanian opening sequence was restored, but the rest was taken straight from Deane, including his compression of the plot and characters - not that any film version of Dracula has ever done much in the way of honoring Stoker's original plot and characters.

The film starred two members of the Broadway run of Deane's play, Bela Lugosi and Edward Van Sloan, and became a stupidly large hit - the most profitable movie Universal released during the Depression. Its influence was quick and certain: as the first American horror movie to explicitly ground its narrative in the supernatural, it opened up a whole new world of storytelling possibilities. It turned Universal overnight into a horror film factory, permitting the creation of the masterful Frankenstein later in the same year. And - I cannot stress this point enough - it was also kind of bad.

Dracula, though directed by Tod Browning, a more than capable filmmaker in the genre, and shot by the amazing Karl Freund, one of the best German cinematographers of the 1920s (making him arguably one of the best cinematographers in history, although he got very few chances to do anything worthwhile after this film), is a perfect example of the worst traits of Hollywood films in the early sound era. A combination of problems, beginning with its budgetary issues and the elder Laemmle's dubious feelings towards the project, and continuing to Browning's alcoholism and outsized grief for the recently deceased Lon Chaney, Sr. left the production in a rocky place (allegedly, it also left Freund to direct most of the London scenes himself, without the benefit of speaking English), and the result is that the bulk of the film, as much as the last two-thirds, feels exactly like what happens when you put a film camera on a theatrical stage to record a live play. Considering that this is frequently cited as the film linking German horror cinema with American horror cinema (a marriage still thriving today), it is peculiar and frustrating that the adjective which best describes it is "uncinematic".

And this much must be said: it's not all that way. The opening 24 minutes, or thereabouts (the film runs for 74), are close to perfection. This is the part of the film concerning the English solicitor Renfield (Dwight Frye) in Transylvania, visiting to deliver some paperwork to the reclusive Count Dracula (Lugosi, but you didn't need me to point that out). It is also a wholly effective immersion in gloomy design and gloomier lighting, creating a mood of suffocating foreboding that's as good as any of its Germanic ancestors. If the whole movie looked as good and as creepy (yes, creepy, even after decades of films have had the chance to improve on it) as the opening, up to the shot of a vampire-crazy Renfield staring out of the hold of a ship with terrifying bug eyes, it would more than deserve its reputation and its place in history.

But 'tis not to be. Almost from the moment that Dracula exits the ship and walks into the Royal Albert Hall, Dracula becomes a crushing bore, not just visually uninspired, but crippled with a barely functional screenplay. Nearly all of the film takes place in the home of Dr. Seward (Herbert Bunston), a pleasant manor on the grounds of his sanitarium, next door to Carfax Abbey, where Dracula has set up his new home, and for a solid 40 minutes, exactly nothing happens.

The characters, loosely adapted from Stoker, include Seward's daughter Mina (Helen Chandler), her fiancé John Harker (David Manners), and her good friend Lucy Weston (Frances Dade). We needn't worry much about Lucy, though, since she falls for Dracula pretty quickly, and becomes his newest vampire bride almost as quickly, and after that she's out of the movie, except for a single shot. Her death is brought to the attention of Prof. Abraham Van Helsing (Edward Van Sloan), a scientist who believes in the occult, insofar as he expects that one day, science will be able to rationally explain all manner of things that go bump in the night.

When I said that nothing happens? I lied. One thing actually does happen, and happen, and happen, and happen. Basically, all the good characters will be sitting around in Seward's parlor, and Dracula will poke his head in and be charming and somehow threatening, Van Helsing will furrow his brow, and declare that the must stop this vampire in their midst. They do not, Mina is attacked offscreen during the night, rinse, repeat. It is as stultifying as any other early-'30s stage adaptation, and if you've seen more than a couple you know just how stultifying that can be. This would be sufficient by itself to earn the movie a thick black mark, except that I haven't mentioned the major plothole concerning Lucy, who dies, is mentioned casually as having become a vampire a good 20 minutes later, and who thereafter ceases to be heard from ever again. Nor the editing of the final scene, which makes time flow like a corkscrew and ends with a truly inexplicable little moment of Van Helsing having to do one more thing, except he doesn't do it and we don't know what it is. There's also the question of how it is that Renfield manages to keep escaping from his cell in the sanitarium to wander around Seward's house, or indeed what possible use he can be to Dracula, since all he does is look crazy and then at the very end explode in a geyser of exposition. And God, let me not even remember the horrible comic relief nurse (Joan Standing) and security guard (Charles Gerrard).

Through all this endless slog of bad writing and flat staging, only three men are able to keep Dracula from sinking into absolute worthlessness: Lugosi, Van Sloan, and Frye. Bela Lugosi's performance as Dracula is, of course, not even worth my description: it's virtually unimaginable that anyone has completely avoided it, and while he was never anywhere near as good an actor as e.g. Lon Chaney or Boris Karloff, when he got to chew hisself a nice thick chunk of scenery, he was absolutely a treat to watch (and of course, the Dracula screenplay gives him plenty to chew on: "Children ahf the night... what music dey make"; "I never... drink... wine"; et cetera ad infinitum). Van Sloan's German accent is very nearly as cartoonish as Lugosi's Hungarian, except that he doesn't come by it honestly, and while the performance is undeniably campy, it's a lot of fun, especially during the late scene when Dracula and Van Helsing face off in one of the all-time great ham festivals of the 1930s. Not to miss out on the fun, Frye gives a completely unhinged performance that ranges from absurdly melodramatic to genuinely disturbing in the space of a few lines, even a syllable - he's always reminded me a little bit of Dudley Manlove in a far different Lugosi vehicle, Plan 9 from Outer Space, only with a dangerous edge that makes his flouncy excesses seem less funny and more terrifying.

But outside of that core - and the uncanny atmosphere of the opening - there's precious little to like about Dracula. Nothing I can do would make the least dent in its historic position - rightfully so, and I do not wish to take away its awesome influence - but there are very few films I can name for which the sniffy phrase "of historical interest only" has been more dreadfully accurate.

Reviews in this series

Dracula (Browning, 1931)

Drácula (Melford, 1931)

Dracula's Daughter (Hillyer, 1936)

Son of Dracula (Siodmak, 1943)

House of Frankenstein (Kenton, 1944)

House of Dracula (Kenton, 1945)

Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein (Barton, 1948)