Positively the same dame

A second review requested by Julian D, with thanks for contributing twice to the Second Quinquennial Antagony & Ecstasy ACS Fundraiser.

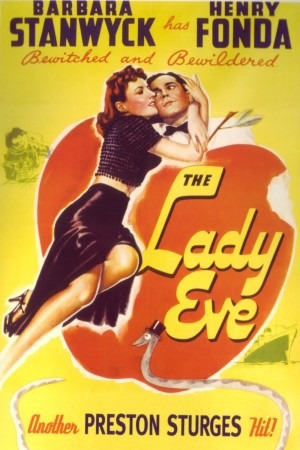

There's nothing more personal and unique than what somebody finds funny - not even what they find scary, maybe not even what they find sexy. The things that make us laugh are as specific to us as a fingerprint. And with that niceness out of the way, may I be so bold as to claim that The Lady Eve, the third film written and directed by the uncommonly great Preston Sturges (a writer-director in an era when those two jobs were jealously segregated) is objectively one of the funniest movies ever made, and that is that.

Better yet, the 1941 film is a remarkable study in what makes a film objectively funny to begin with. It's not the only comedy with a nigh-perfect screenplay; the perfection of Sturges's writing, from an Oscar-nominated story by Monckton Hoffe, is however pure in a way that the perfection of, say, Some Like It Hot is not. For the latter is full of idiosyncracies and structural weirdness that should destroy it instead of force it up to greatness. The Lady Eve, however, is a model for the entire corpus of American film comedy, the kind of script that you want to hold up and say "this is what you do" to aspiring writers. It is structurally flawless, with a second half that mirrors the first half and a bridge between them that gives the audience a chance to relax and re-orient. The dialogue is precisely shaped and timed to build characters at the exact pace Sturges wants them to be built, telling us an enormous amount in what is said, how it is said, and most of all, why and when it is said. It helps things out that the movie boasts a murderer's row of on-screen talent, with a shamefully high number of people at or near their all-time best work, but this is as close at it gets to an actor-proof comedy; I can imagine a recast version of it that is worse of course, but not really one that's no good at all. The writing is simply too goddamn good for that.

It is one of the last great screwball comedies of the '30s tradition, with cunning fast-talking women and hapless idiot men. A ship traveling up the east coast of the Americas makes an unscheduled stop to pick up a single passenger; this could only be a luxury afforded to the very rich, and that is absolutely the right description for mild, dimwitted Charles Pike (Henry Fonda), heir apparent to the mighty Pike Ale ("the ale that won for Yale") fortune. He only cares about one thing: cataloguing rare snakes. And it is for the reason that he's been in the Amazon for the last year. Nothing about him makes him much for social graces, which is why he's so baffled by the besotted attention of every woman on the vessel. But it's one particular woman he needs to be wary of: Jean Harrington (Barbara Stanwyck), traveling with her father "Colonel" Harrington (Charles Coburn), the both of them trained in the fine art of hustling people at cards. Ideally mild, dimwitted, wealthy people. Unluckily, Jean falls in love with Charles while she's busy tricking him into falling in love with her, leading her to sabotage her father's dogged attempts to fleece the boy. Tragically, Charles's endless distrustful bodyguard "Muggsy" Murgatroyd (William Demarest) learns of the Harringtons' identity just when they've given up their shenanigans, and Charles brutally drops Jean. And this leads her to vow the most punishing kind of revenge she can concoct: in the guise of Lady Eve Sidwich, fake niece to fake nobleman Sir Alfred McGlennan Keith (Eric Blore), she plots to kick Charles square in the male ego.

The two halves of the film echo each other in many little ways, from basic scenario (Jean falling for Charles despite his money vs. Charles falling for "Eve" because of hers), to the placement of exact gags. Both of them are introduced with a terrifyingly perfect line of acidity given to Stanwyck on a silver platter, who pays back her writer-director by delivering those lines with with the exact energy that drives the next 40 minutes: "Gee, I hope he's rich. I hope he thinks he's a wizard at cards" she bursts out with the giddy anticipation of a child on Christmas Eve - it's Jean's very first line in the whole movie, and between those words and the fever pitch pace of Stanwyck's delivery, we know or can pretty much figure out everything we'll need to know about her. The knowing cynicism, the high-energy prattle. And high-energy prattle is one of the great weapons in The Lady Eve's quiver; all screwball films rely on a female lead who can speak a mile a minute, and the absolute best of them use that as a character and story device as much as a comic element (what is His Girl Friday without Rosalind Russell's rapid-fire newspaperman argot?), but I don't think there's another film out there where the high-speed delivery is so clearly a choice made by the character as a way of getting the upper hand on a mark.

This, of course, is what happens when Stanwyck gets involved: not just a great actor (not just, arguably, the greatest actor of her generation) with peerless comic chops, but one who had a gift like nobody ever did for showing us thoughtfulness and calculation and all the things her characters aren't saying in favor of the things she finally elects to vocalise. Jean Harrington is absolutely the twin sister of Phyllis Dietrichson from Double Indemnity, so many moves ahead of her opponent in her mind that she's already working on the next game. One is a comic hero, the other a noir villain, but that's not such an impossible gap to clear. And it's never narrower than in the other great one-liner Stanwyck gets to open the second half of the movie: "I need him like the axe needs the turkey", underplayed and reflective, delivered as much through the way she drops her eyebrow as by the self-amusement twisting her mouth.

One could go on and on praising Stanwyck, because it's maybe her best performance, maybe the best comic performance in Hollywood history, maybe the best performance in English cinema. It's easy to go overboard. But she's merely one element that goes into the absolutely all-over perfection of The Lady Eve, the standout in a tremendous ensemble: Fonda, gamely playing a vanilla idiot, is more a matter of perfect casting than inspired acting (the one real flaw I can spot in the movie is that Jean is much too smart and good a character to grow so fond of such a nebbish), but when he's the arguable weak link, we're clearly facing one of the greatest collection of actors ever assembled for a comedy. Coburn's mingling of impatience and fatherly pride; Demarest's pathetic sharpness; Eugene Pallette's thick bellowing and besotted creepiness as the elder Mr. Pike; these are not persona-shattering turns by great supporting actors, and yet none of the actors in question ever really topped this version of their usual role.

Besides all that, it's probably Sturges's most tightly-made film, the one where he used editing most dauntlessly to build and punctuate gags; it was his first collaboration with Stuart Gilmore, who edited all of the writer-director's comic masterworks to immediately follow - Sullivan's Travels, The Palm Beach Story, The Miracle of Morgan's Creek. Any of those films could serve as a case study in how precise timing and cutting can augment film comedy, and yet none of them have a single moment as perfect as Eve's dining room sequence, a collection of reverse shots along shifting eyelines that perfectly express Charles's terror and bafflement, or its climactic train scene, in which storms and close-ups on pounding locomotion ironically provide melodramatic counterpoint and sexually suggestive visual gags. Amusingly enough, the film's most famous scene and possibly its best is the one with no editing at all: Jean plays with Charles's hair in a single shot lasting more than three minutes that is possibly the most sexually explicit sequence in American cinema of the 1940s, culminating in what I can only describe as a metaphorical orgasm. It's erotic and hilarious simultaneously; as much an act of craft as eros, with Stanwyck and Fonda sparking off some of the most electrifying screen chemistry imaginable.

It's the crowning moment of a movie that seems like it can do anything: run at full steam and then slow down for a scene of tenderness without letting us see the downshift; play with verbal dexterity, broad farce, and gaudy slapstick, and make all of them seem equally airy and effortless; and allow Stanwyck to create an enormously vivid and deep character of self-aware desire, professional acumen, and buried wounds out of the stock material of a daffy romantic lead in a comedy. It is one of the most triumphant delights of pre-WWII Hollywood, the comedy upon which Sturges's great and well-earned reputation most securely resides, and there is not a single frame of it I would change, move, or take away.

There's nothing more personal and unique than what somebody finds funny - not even what they find scary, maybe not even what they find sexy. The things that make us laugh are as specific to us as a fingerprint. And with that niceness out of the way, may I be so bold as to claim that The Lady Eve, the third film written and directed by the uncommonly great Preston Sturges (a writer-director in an era when those two jobs were jealously segregated) is objectively one of the funniest movies ever made, and that is that.

Better yet, the 1941 film is a remarkable study in what makes a film objectively funny to begin with. It's not the only comedy with a nigh-perfect screenplay; the perfection of Sturges's writing, from an Oscar-nominated story by Monckton Hoffe, is however pure in a way that the perfection of, say, Some Like It Hot is not. For the latter is full of idiosyncracies and structural weirdness that should destroy it instead of force it up to greatness. The Lady Eve, however, is a model for the entire corpus of American film comedy, the kind of script that you want to hold up and say "this is what you do" to aspiring writers. It is structurally flawless, with a second half that mirrors the first half and a bridge between them that gives the audience a chance to relax and re-orient. The dialogue is precisely shaped and timed to build characters at the exact pace Sturges wants them to be built, telling us an enormous amount in what is said, how it is said, and most of all, why and when it is said. It helps things out that the movie boasts a murderer's row of on-screen talent, with a shamefully high number of people at or near their all-time best work, but this is as close at it gets to an actor-proof comedy; I can imagine a recast version of it that is worse of course, but not really one that's no good at all. The writing is simply too goddamn good for that.

It is one of the last great screwball comedies of the '30s tradition, with cunning fast-talking women and hapless idiot men. A ship traveling up the east coast of the Americas makes an unscheduled stop to pick up a single passenger; this could only be a luxury afforded to the very rich, and that is absolutely the right description for mild, dimwitted Charles Pike (Henry Fonda), heir apparent to the mighty Pike Ale ("the ale that won for Yale") fortune. He only cares about one thing: cataloguing rare snakes. And it is for the reason that he's been in the Amazon for the last year. Nothing about him makes him much for social graces, which is why he's so baffled by the besotted attention of every woman on the vessel. But it's one particular woman he needs to be wary of: Jean Harrington (Barbara Stanwyck), traveling with her father "Colonel" Harrington (Charles Coburn), the both of them trained in the fine art of hustling people at cards. Ideally mild, dimwitted, wealthy people. Unluckily, Jean falls in love with Charles while she's busy tricking him into falling in love with her, leading her to sabotage her father's dogged attempts to fleece the boy. Tragically, Charles's endless distrustful bodyguard "Muggsy" Murgatroyd (William Demarest) learns of the Harringtons' identity just when they've given up their shenanigans, and Charles brutally drops Jean. And this leads her to vow the most punishing kind of revenge she can concoct: in the guise of Lady Eve Sidwich, fake niece to fake nobleman Sir Alfred McGlennan Keith (Eric Blore), she plots to kick Charles square in the male ego.

The two halves of the film echo each other in many little ways, from basic scenario (Jean falling for Charles despite his money vs. Charles falling for "Eve" because of hers), to the placement of exact gags. Both of them are introduced with a terrifyingly perfect line of acidity given to Stanwyck on a silver platter, who pays back her writer-director by delivering those lines with with the exact energy that drives the next 40 minutes: "Gee, I hope he's rich. I hope he thinks he's a wizard at cards" she bursts out with the giddy anticipation of a child on Christmas Eve - it's Jean's very first line in the whole movie, and between those words and the fever pitch pace of Stanwyck's delivery, we know or can pretty much figure out everything we'll need to know about her. The knowing cynicism, the high-energy prattle. And high-energy prattle is one of the great weapons in The Lady Eve's quiver; all screwball films rely on a female lead who can speak a mile a minute, and the absolute best of them use that as a character and story device as much as a comic element (what is His Girl Friday without Rosalind Russell's rapid-fire newspaperman argot?), but I don't think there's another film out there where the high-speed delivery is so clearly a choice made by the character as a way of getting the upper hand on a mark.

This, of course, is what happens when Stanwyck gets involved: not just a great actor (not just, arguably, the greatest actor of her generation) with peerless comic chops, but one who had a gift like nobody ever did for showing us thoughtfulness and calculation and all the things her characters aren't saying in favor of the things she finally elects to vocalise. Jean Harrington is absolutely the twin sister of Phyllis Dietrichson from Double Indemnity, so many moves ahead of her opponent in her mind that she's already working on the next game. One is a comic hero, the other a noir villain, but that's not such an impossible gap to clear. And it's never narrower than in the other great one-liner Stanwyck gets to open the second half of the movie: "I need him like the axe needs the turkey", underplayed and reflective, delivered as much through the way she drops her eyebrow as by the self-amusement twisting her mouth.

One could go on and on praising Stanwyck, because it's maybe her best performance, maybe the best comic performance in Hollywood history, maybe the best performance in English cinema. It's easy to go overboard. But she's merely one element that goes into the absolutely all-over perfection of The Lady Eve, the standout in a tremendous ensemble: Fonda, gamely playing a vanilla idiot, is more a matter of perfect casting than inspired acting (the one real flaw I can spot in the movie is that Jean is much too smart and good a character to grow so fond of such a nebbish), but when he's the arguable weak link, we're clearly facing one of the greatest collection of actors ever assembled for a comedy. Coburn's mingling of impatience and fatherly pride; Demarest's pathetic sharpness; Eugene Pallette's thick bellowing and besotted creepiness as the elder Mr. Pike; these are not persona-shattering turns by great supporting actors, and yet none of the actors in question ever really topped this version of their usual role.

Besides all that, it's probably Sturges's most tightly-made film, the one where he used editing most dauntlessly to build and punctuate gags; it was his first collaboration with Stuart Gilmore, who edited all of the writer-director's comic masterworks to immediately follow - Sullivan's Travels, The Palm Beach Story, The Miracle of Morgan's Creek. Any of those films could serve as a case study in how precise timing and cutting can augment film comedy, and yet none of them have a single moment as perfect as Eve's dining room sequence, a collection of reverse shots along shifting eyelines that perfectly express Charles's terror and bafflement, or its climactic train scene, in which storms and close-ups on pounding locomotion ironically provide melodramatic counterpoint and sexually suggestive visual gags. Amusingly enough, the film's most famous scene and possibly its best is the one with no editing at all: Jean plays with Charles's hair in a single shot lasting more than three minutes that is possibly the most sexually explicit sequence in American cinema of the 1940s, culminating in what I can only describe as a metaphorical orgasm. It's erotic and hilarious simultaneously; as much an act of craft as eros, with Stanwyck and Fonda sparking off some of the most electrifying screen chemistry imaginable.

It's the crowning moment of a movie that seems like it can do anything: run at full steam and then slow down for a scene of tenderness without letting us see the downshift; play with verbal dexterity, broad farce, and gaudy slapstick, and make all of them seem equally airy and effortless; and allow Stanwyck to create an enormously vivid and deep character of self-aware desire, professional acumen, and buried wounds out of the stock material of a daffy romantic lead in a comedy. It is one of the most triumphant delights of pre-WWII Hollywood, the comedy upon which Sturges's great and well-earned reputation most securely resides, and there is not a single frame of it I would change, move, or take away.

Categories: best films of all time, comedies, farce, romcoms