Universal Horror: ¡Es el vampiro!

The modern American trend of remaking successful foreign language films on the grounds that "nobody likes subtitles" is insulting, but unlike so many moviegoing insults, is not a terribly new development; it is indeed as old as sound cinema itself. And frankly, the current guise of that trend - a blink-and-miss-it limited release followed after a couple of years by the new Hollywood version - is rather sedate next to the old school method, in which the original studio, and in some cases the original filmmakers, would produce multiple versions of the film in different languages right at the start. I do not know how widespread this trend was, but it was at any rate not uncommon in Europe; even filmmakers as prominent as Fritz Lang and Carl Theodor Dreyer have examples in their filmographies of duplicate films in variant languages.

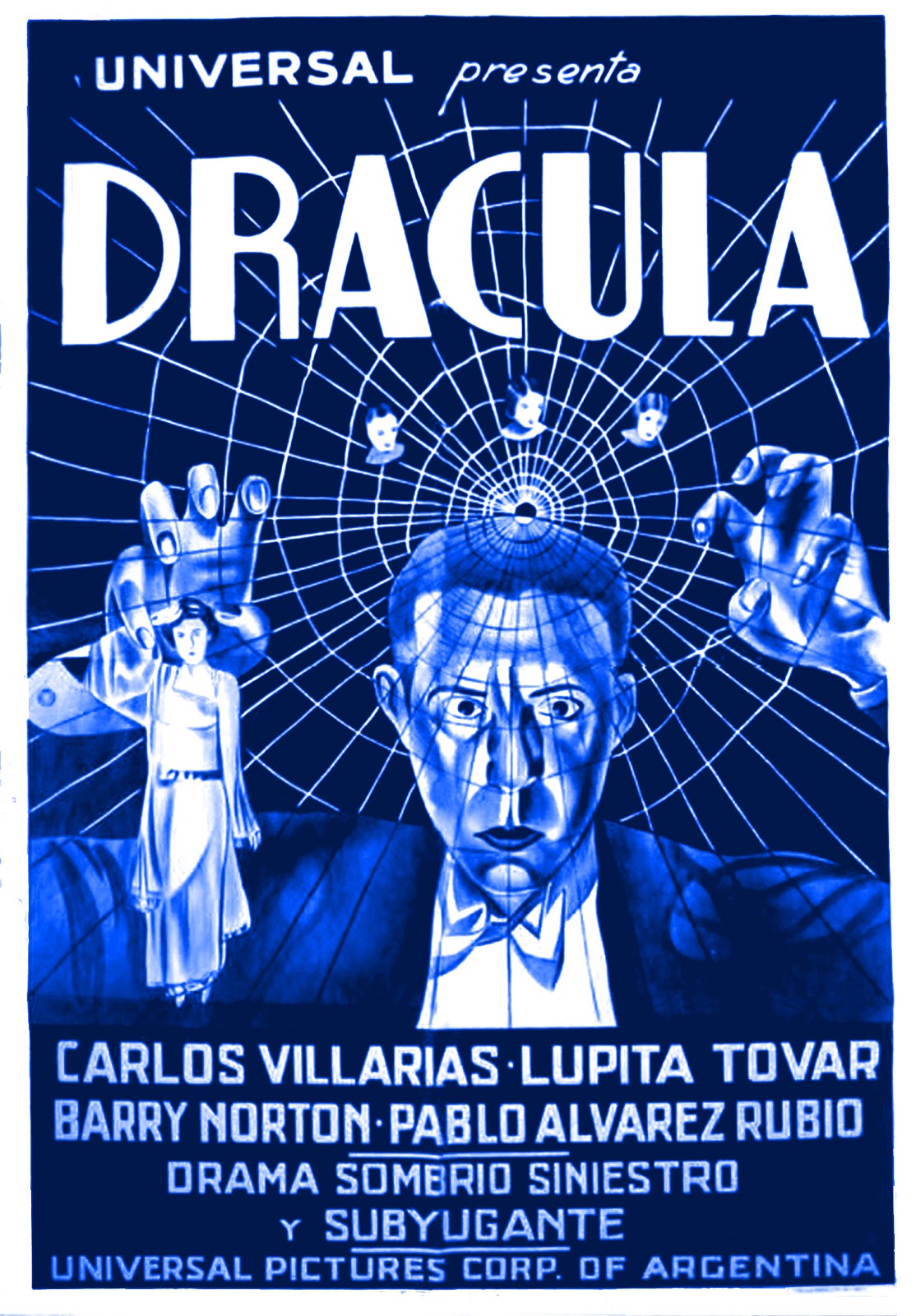

But we're here to talk about Universal's horror films, and the interesting thing that happened at that studio in 1930. While Tod Browning was directing his incredibly important version of Dracula during the day, a far less prominent nobody called George Melford would show up at night to shoot a Spanish-language Drácula intended for the Mexican market with a cast cobbled together from Spain, Mexico, and South America - none of them speaking English, and Melford knowing no Spanish, mind you - using not only the same sets as the Browning film, but also the same basic script, and if some of the early scenes are to be judged, the same shot list. So carefully did the Spanish-language film track the better-known English version that its Spanish lead, Carlos Villarias, wore a hairpiece identical to Bela Lugosi's so that wide shots and some special effects could be cribbed from the higher-budget production.

Yet for all that the films ought to be basically identical, Melford & company's Drácula is a surprisingly different beast. It is not absolutely, unmistakably superior - there are several key ways in which the better-known film is in fact better - but on the whole, the quick cash-in proves to be a much more mature and comprehensible work, answering most of the biggest problems I raised in regards to the Browning variation, even as it makes a couple of mistakes that Browning was able to avoid. I hate to turn this into a simple compare 'n contrast between Dracula and Drácula (please keep an eye out for that diacritic, it's going to be the only way I distinguish the two films from here on out), but at least to start, that's the simplest way and - given that I expect that even Spanish speakers are more familiar with the English film- probably the easiest to follow.

From a narrative standpoint, the most notable change to Drácula is that there's just plumb more of it. 29 minutes more, in fact, mostly just extended versions of scenes that were already there, giving them room to breathe and get the point across without having that dreadfully choppy "here's a new thing to keep track of - move along!" rhythm of Dracula;. The added length also gives Drácula a chance to correct the most howling plot hole of Dracula the ultimate fate of Lucy Weston. In the other film, Van Helsing confidently assures Mina that they'll take care of her vampire friend, and then the matter is dropped. Here, Van Helsing (Eduardo Arozamena) and Juan Harker (Barry Norton, who did in fact speak English, so I lied up there; but he's not American, despite his arch-gringo name) steal away to the graveyard where Lucía (Carmen Guerrero) lies buried; there is a still shot of the foggy outside pierced by a woman's scream, and the two men exit the graveyard, Van Helsing reassuring Harker that they have just done a good act, freeing her soul. Maybe not the most action-packed scene in horror cinema, but at least we aren't left hanging.<

Most of the other script changes are relatively tiny, limited mostly to a few lines here or there that clarify things left fuzzy in Dracula, such as Van Helsing's explanation for why he stays behind in the crypt (it's to exorcise the demon from Renfield's (Pablo Álvarez Rubio) corpse), or slightly fuller expansions of what exactly is happening to Mina - that is, Eva (Lupita Tovar) - and when. Indeed, Drácula has a much more sensible chronology; whereas the last thirty minutes of Dracula could take place over anything from one night to a couple of weeks, dialogue here makes it fairly clear that everything in the second half takes place in one night, about two weeks after Drácula's arrival in whatever unnamed city this version takes place in. Dialogue also makes the shocking point that the film is set in either 1930 or 1931, though virtually every reviewer I've encountered of the standard Dracula agrees that it's sometime indefinitely in the 1890s. Also, befitting its largely Catholic target audience, Drácula has a much greater emphasis on religion - characters are always crossing themselves, and such.

But after the resolution of that hanging Lucía plotline, the most significant narrative shift centers upon Renfield, poor crazy bug-eater that he is. A lot of it is something as simple as how Melford blocks the scenes differently from Browning (or Karl Freund, whoever really directed those London interiors). In Dracula, Renfield always wanders in from the outer reaches of the Seward house, an impossible situation - if he's that dangerous, no way would Dr. Seward (here played by José Soriano Viosca) be so sanguine about a madman in his very home. In Drácula, Renfield always approaches from the outside - a teeny shift that makes everything much easier to believe. His characterisation is also generally more sensible than in the other film; what looks like unmotivated waffling between helping his master and helping Van Helsing here reads as a smug psycho who enjoys taunting his enemies, but sometimes gives too much away by accident - a reading that is helped out considerably by the vastly expanded interview between Van Helsing and Renfield at the professor's arrival to the sanitarium.

Now, as written, I'm inclined to give Drácula the full victory - I can't think of a single point where its divergences from Dracula's script don't serve to improve it. As produced, though, things get a bit crazy: almost everything that was good in Dracula is just kind of so-so here, and vice-versa. To start with, there's the opening sequence in Transylvania: shot by Freund in Dracula with the most crushing blacks imaginable, it was a masterpiece of mood creation. George Robinson, the DP on Drácula, makes an utterly idiotic mistake, particularly since I would imagine he had access to Freund's dailies: he over-lights Castle Dracula. All the pitch-black corners are now merely charcoal grey, and the general feeling is that the Count seems to have picked himself up some halogen floor lamps recently.

That said, most of the effects in this sequence are just as good as in Dracula (as they ought to be; many of them are the exact same shots), and in one important instance, significantly better: now we actually get to see Drácula rising from his coffin, accompanied by a puff of smoke. I never could quite understand why Browning's film always panned or cut away from the opening coffins - a taste issue, perhaps? - and it's tremendously gratifying to see that added back in here.

A weird exception to that general rule is in the boat passage scene (the boat has been renamed Elsie from Vesta, don't ask me why): all of the establishing shots of the boat caught in the storm have been removed. This makes absolutely no sense on any level I can imagine and it serves to suck most of the drama out of this sequence. It gets worse still in the shot where the dock authorities find Renfield hiding in the cargo hold: arguably the single best shot in Browning's Dracula, the framing and lighting are entirely dull in this case, robbing a haunting moment of all its impact.

But when the action gets to the city, the film's visuals suddenly improve immensely, far outstripping Dracula. That film was barbarically focused on reminding the audience that it was, in fact, a stage adaptation: most of the action was filmed from one angle, scene after scene, with virtually nothing but wide shots. Melford mixes things up quite a bit: let's shoot this scene from behind the couch, let's have some nice close-ups here, let's make good use of the door leading to the portico to frame characters and action. And - wonder of wonders! miracle of miracles! - his camera moves! Nothing that would make Mizoguchi sweat, but he uses subtle dollies and pans in ways that Browning (or Freund) seemed constitutionally averse to. At the very least, this is more interesting to look at than Dracula; at best, it proves that nobody director can run rings around a star filmmaker if he's not crippled by alcohol.

As to the acting: it is mostly good where Dracula is bad, and bad where Dracula is good. There are two exceptions: neither Soriano Viosca nor Herbert Bunston could do much of anything with the hopelessly dull Dr. Seward, for one. On the other side, Arozamena's take on Van Helsing is quite fascinating: not by any means a standard interpretation of the character, but compelling for just that reason, his gruff sensibility is light years from Edward Van Sloan loony approach to the character, but almost as memorable.

As Eva and Juan, Tovar and Norton run rings around Helen Chandler and David Manners. For a start, they actually have chemistry, to spare. And Tovar in particular brings a living womanly quality to the character that Chandler played as an ambulatory chuck of wood. If I were going to indulge in cultural stereotypes, I'd mention something about Latina sensuality here, and I would have thus indicated to no small degree why Eva is a much more active and interesting character than Mina.

Then, we've got Renfield and the Count. Álvarez Rubio isn't bad per se, but he won't make anybody forget Dwight Frye. His "madman" is more like a snotty teen with a case of the giggles, and only the "millions of rats!" monologue actually approaches anything like the constant warped eeriness that Frye carried around like a well-worn coat. He's really just not very distinctive, that's all. As for Villarias, well... fuck. Look, Lugosi's performance as Dracula is the vampire, and there's no competing with that. But Villarias would be a disaster no matter what. If Lugosi was all animalistic smoldering and hideous charisma, Villarias... he just kind of opens his eyes till they bug out, and bares his teeth in a grin that makes him look like an applicant to clown school. He also has exactly zero of the seductive power that pretty much defined Lugosi's screen presence. It's a very silly Drácula we see onscreen here, and if the film had any real horrific suspense to speak of, Villarias big ol' smile would pretty much smother it in the crib.

Even so, he's not enough to keep Drácula from collapsing in on itself - though he almost single-handedly keeps it from being a really fine '30s horror movie. As it is, the film must settle for just being good enough. That is still more than the more famous Dracula can claim, and I must be honest: if I were to watch one of these again any time soon, I am absolutely certain that I'd go for the Spanish one. Sorry, Bela.

Reviews in this series

Dracula (Browning, 1931)

Drácula (Melford, 1931)

Dracula's Daughter (Hillyer, 1936)

Son of Dracula (Siodmak, 1943)

House of Frankenstein (Kenton, 1944)

House of Dracula (Kenton, 1945)

Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein (Barton, 1948)

But we're here to talk about Universal's horror films, and the interesting thing that happened at that studio in 1930. While Tod Browning was directing his incredibly important version of Dracula during the day, a far less prominent nobody called George Melford would show up at night to shoot a Spanish-language Drácula intended for the Mexican market with a cast cobbled together from Spain, Mexico, and South America - none of them speaking English, and Melford knowing no Spanish, mind you - using not only the same sets as the Browning film, but also the same basic script, and if some of the early scenes are to be judged, the same shot list. So carefully did the Spanish-language film track the better-known English version that its Spanish lead, Carlos Villarias, wore a hairpiece identical to Bela Lugosi's so that wide shots and some special effects could be cribbed from the higher-budget production.

Yet for all that the films ought to be basically identical, Melford & company's Drácula is a surprisingly different beast. It is not absolutely, unmistakably superior - there are several key ways in which the better-known film is in fact better - but on the whole, the quick cash-in proves to be a much more mature and comprehensible work, answering most of the biggest problems I raised in regards to the Browning variation, even as it makes a couple of mistakes that Browning was able to avoid. I hate to turn this into a simple compare 'n contrast between Dracula and Drácula (please keep an eye out for that diacritic, it's going to be the only way I distinguish the two films from here on out), but at least to start, that's the simplest way and - given that I expect that even Spanish speakers are more familiar with the English film- probably the easiest to follow.

From a narrative standpoint, the most notable change to Drácula is that there's just plumb more of it. 29 minutes more, in fact, mostly just extended versions of scenes that were already there, giving them room to breathe and get the point across without having that dreadfully choppy "here's a new thing to keep track of - move along!" rhythm of Dracula;. The added length also gives Drácula a chance to correct the most howling plot hole of Dracula the ultimate fate of Lucy Weston. In the other film, Van Helsing confidently assures Mina that they'll take care of her vampire friend, and then the matter is dropped. Here, Van Helsing (Eduardo Arozamena) and Juan Harker (Barry Norton, who did in fact speak English, so I lied up there; but he's not American, despite his arch-gringo name) steal away to the graveyard where Lucía (Carmen Guerrero) lies buried; there is a still shot of the foggy outside pierced by a woman's scream, and the two men exit the graveyard, Van Helsing reassuring Harker that they have just done a good act, freeing her soul. Maybe not the most action-packed scene in horror cinema, but at least we aren't left hanging.<

Most of the other script changes are relatively tiny, limited mostly to a few lines here or there that clarify things left fuzzy in Dracula, such as Van Helsing's explanation for why he stays behind in the crypt (it's to exorcise the demon from Renfield's (Pablo Álvarez Rubio) corpse), or slightly fuller expansions of what exactly is happening to Mina - that is, Eva (Lupita Tovar) - and when. Indeed, Drácula has a much more sensible chronology; whereas the last thirty minutes of Dracula could take place over anything from one night to a couple of weeks, dialogue here makes it fairly clear that everything in the second half takes place in one night, about two weeks after Drácula's arrival in whatever unnamed city this version takes place in. Dialogue also makes the shocking point that the film is set in either 1930 or 1931, though virtually every reviewer I've encountered of the standard Dracula agrees that it's sometime indefinitely in the 1890s. Also, befitting its largely Catholic target audience, Drácula has a much greater emphasis on religion - characters are always crossing themselves, and such.

But after the resolution of that hanging Lucía plotline, the most significant narrative shift centers upon Renfield, poor crazy bug-eater that he is. A lot of it is something as simple as how Melford blocks the scenes differently from Browning (or Karl Freund, whoever really directed those London interiors). In Dracula, Renfield always wanders in from the outer reaches of the Seward house, an impossible situation - if he's that dangerous, no way would Dr. Seward (here played by José Soriano Viosca) be so sanguine about a madman in his very home. In Drácula, Renfield always approaches from the outside - a teeny shift that makes everything much easier to believe. His characterisation is also generally more sensible than in the other film; what looks like unmotivated waffling between helping his master and helping Van Helsing here reads as a smug psycho who enjoys taunting his enemies, but sometimes gives too much away by accident - a reading that is helped out considerably by the vastly expanded interview between Van Helsing and Renfield at the professor's arrival to the sanitarium.

Now, as written, I'm inclined to give Drácula the full victory - I can't think of a single point where its divergences from Dracula's script don't serve to improve it. As produced, though, things get a bit crazy: almost everything that was good in Dracula is just kind of so-so here, and vice-versa. To start with, there's the opening sequence in Transylvania: shot by Freund in Dracula with the most crushing blacks imaginable, it was a masterpiece of mood creation. George Robinson, the DP on Drácula, makes an utterly idiotic mistake, particularly since I would imagine he had access to Freund's dailies: he over-lights Castle Dracula. All the pitch-black corners are now merely charcoal grey, and the general feeling is that the Count seems to have picked himself up some halogen floor lamps recently.

That said, most of the effects in this sequence are just as good as in Dracula (as they ought to be; many of them are the exact same shots), and in one important instance, significantly better: now we actually get to see Drácula rising from his coffin, accompanied by a puff of smoke. I never could quite understand why Browning's film always panned or cut away from the opening coffins - a taste issue, perhaps? - and it's tremendously gratifying to see that added back in here.

A weird exception to that general rule is in the boat passage scene (the boat has been renamed Elsie from Vesta, don't ask me why): all of the establishing shots of the boat caught in the storm have been removed. This makes absolutely no sense on any level I can imagine and it serves to suck most of the drama out of this sequence. It gets worse still in the shot where the dock authorities find Renfield hiding in the cargo hold: arguably the single best shot in Browning's Dracula, the framing and lighting are entirely dull in this case, robbing a haunting moment of all its impact.

But when the action gets to the city, the film's visuals suddenly improve immensely, far outstripping Dracula. That film was barbarically focused on reminding the audience that it was, in fact, a stage adaptation: most of the action was filmed from one angle, scene after scene, with virtually nothing but wide shots. Melford mixes things up quite a bit: let's shoot this scene from behind the couch, let's have some nice close-ups here, let's make good use of the door leading to the portico to frame characters and action. And - wonder of wonders! miracle of miracles! - his camera moves! Nothing that would make Mizoguchi sweat, but he uses subtle dollies and pans in ways that Browning (or Freund) seemed constitutionally averse to. At the very least, this is more interesting to look at than Dracula; at best, it proves that nobody director can run rings around a star filmmaker if he's not crippled by alcohol.

As to the acting: it is mostly good where Dracula is bad, and bad where Dracula is good. There are two exceptions: neither Soriano Viosca nor Herbert Bunston could do much of anything with the hopelessly dull Dr. Seward, for one. On the other side, Arozamena's take on Van Helsing is quite fascinating: not by any means a standard interpretation of the character, but compelling for just that reason, his gruff sensibility is light years from Edward Van Sloan loony approach to the character, but almost as memorable.

As Eva and Juan, Tovar and Norton run rings around Helen Chandler and David Manners. For a start, they actually have chemistry, to spare. And Tovar in particular brings a living womanly quality to the character that Chandler played as an ambulatory chuck of wood. If I were going to indulge in cultural stereotypes, I'd mention something about Latina sensuality here, and I would have thus indicated to no small degree why Eva is a much more active and interesting character than Mina.

Then, we've got Renfield and the Count. Álvarez Rubio isn't bad per se, but he won't make anybody forget Dwight Frye. His "madman" is more like a snotty teen with a case of the giggles, and only the "millions of rats!" monologue actually approaches anything like the constant warped eeriness that Frye carried around like a well-worn coat. He's really just not very distinctive, that's all. As for Villarias, well... fuck. Look, Lugosi's performance as Dracula is the vampire, and there's no competing with that. But Villarias would be a disaster no matter what. If Lugosi was all animalistic smoldering and hideous charisma, Villarias... he just kind of opens his eyes till they bug out, and bares his teeth in a grin that makes him look like an applicant to clown school. He also has exactly zero of the seductive power that pretty much defined Lugosi's screen presence. It's a very silly Drácula we see onscreen here, and if the film had any real horrific suspense to speak of, Villarias big ol' smile would pretty much smother it in the crib.

Even so, he's not enough to keep Drácula from collapsing in on itself - though he almost single-handedly keeps it from being a really fine '30s horror movie. As it is, the film must settle for just being good enough. That is still more than the more famous Dracula can claim, and I must be honest: if I were to watch one of these again any time soon, I am absolutely certain that I'd go for the Spanish one. Sorry, Bela.

Reviews in this series

Dracula (Browning, 1931)

Drácula (Melford, 1931)

Dracula's Daughter (Hillyer, 1936)

Son of Dracula (Siodmak, 1943)

House of Frankenstein (Kenton, 1944)

House of Dracula (Kenton, 1945)

Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein (Barton, 1948)