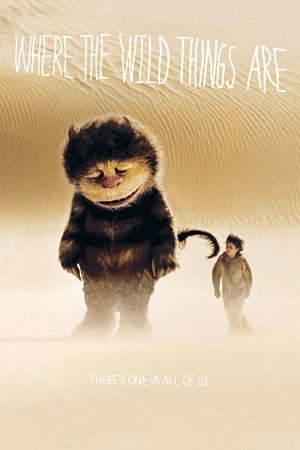

Wild at heart

Spike Jonze and Dave Eggers's adaptation of Maurice Sendak's perfect and nearly wordless picture book Where the Wild Things Are, the story of a little boy named Max (Max Records) who gets so fed up with his mom (Catherine Keener) and his life that he runs off to find a place where large and not altogether friendly monsters live and play and fight in the woods, has so far received the kind of mixed reception that can only be earned by a love-it or hate-it movie, and indeed that is what I've found to be the case: with but a handful of exceptions, people are either absolutely transfixed by this film's depiction of childhood trauma, or they are violently turned off by the filmmaker's narrowness of emotional vision. I am honestly quite impressed by anyone who can be that sure of their opinion; there's hardly been a moment since I saw it that I haven't been trying to figure out exactly what the hell I feel about it, and frankly there's a bit of a love-it or hate-it thing going on inside my brain. With all due respect to the many smart and well-spoken champions and opponents of the film, I think the only reasonable response (for me at least) is to be completely muddled about the whole thing.

Beginning with what is unabashedly brilliant about the film (not because I want to be nice, but because it's the only thing that's easy to grapple with), it looks as amazing and beautiful as anything else you will see in theatres right now. For a start, the wild things themselves are among the most perfectly-realised fantasy creatures in movie history: a nigh-miraculous marriage of full-body suits made with as much love and attention as anything to ever come out of Jim Henson's Creature Shop and incredibly, almost uncannily expressive CGI facial features, particularly their deep, soulful eyes. It's not hard to understand why young Max would be attracted to these beasts, for they are so warm and full-bodied that one longs to jump into the screen and join in their pile-up right along with him.

Right along side the design of the wild things is the look of their world, courtesy of K.K. Barrett, whose strong work in Jonze's previous features (as well as Sofia Coppola's Marie Antoinette) doesn't even begin to suggest that he had something as imaginative and otherworldly as the giant orbs that make up the things' homes and the vast fort that Max commissions from them. All of these visual splendors are captured by Jonze and his regular cinematographer Lance Acord with a level of sophistication unmatched elsewhere in the careers. Jonze's direction in Being John Malkovich and even more so in Adaptation. always struck me as being deliberately invisible, permitting Charlie Kaufman's hallucinatory screenplays to speak for themselves without being prodded along by funky visuals; to a certain degree he continues that trend in Wild Things, but at the same time the direction is certain and intelligent, keeping us tightly yoked to Max's POV so that the things seem to tower over us in their majesty and terror, and yet when the need arises to bring things to a more intimate scale, he knows exactly when to use a wider shot to bring the creatures and their environment down to a manageable size. Hell, he even manages to make the colossally over-used handheld camera aesthetic that ceased being inventive or appealing years ago seem positively essential. And Acord, well, the film looks beautiful without having to resort to postcard-friendly shots of landscaping; indeed, the way that lighting is used in the film could almost be lovely if it didn't have a certain air of unearthliness to it.

And then, there's the movie as a narrative experience, and well, I just don't know. It's not that I'm bothered with the degree to which it's not Sendak's book. Sendak's book is perfect in a way that no feature film could ever be perfect, since they are not permitted to be so compact. In fact, Jonze and Eggers (they co-wrote, despite the number of reviews that seem to lay all the blame or credit squarely at Eggers's feet) probably have made the most credible adaptation of the slim volume possible, because they have not tried to expand Sendak's tiny scenario into something sprawling; they have used it as the basis for something as personal to themselves as Sendak's book was to him. Therein lies the rub.

The extended plot greatly enlarges the details of Max's home life: with his sister Claire (Pepita Emmerichs) entering the strange world of teenagerdom, his father conspicuously absent save for a somewhat ominous globe bearing the plaque, "This world is yours - Dad", and his mother trying desperately to hold things together at work, keep a good home for her kids, and still pursue a personal life, the boy believes like most children that he isn't getting enough attention, and he acts out violently. In the opening sequence, he gets revenge on his sister's friends by trashing her room; later on he vents his anger at his mom bringing a man to the house (played by Mark Ruffalo in what is not so much a glorified cameo as a featured extra role), by screaming and standing on the kitchen counter threatening to eat her, and biting her on the shoulder - this last event freaks her out so badly that she starts to scream back, and he runs out of the house, and in a fairly delicate transition implied almost solely by the editing, starts to fantasise about taking a boat to a far-away forest on the edge of a desert by the sea, where the wild things are.

The wild things themselves are also expanded, given distinct personalities and voiced by a cast of famous people that, shockingly, don't overwhelm their characters. The most important thing in Max's eyes, since they are the most similar, is Carol (a deliberate echo of Claire, else I'm no judge), the monster whose response to being ignored by those he loves is to lash out with terrible acts of violence. Carol is voiced by James Gandolfini, brilliantly; though at first there's the usual "why is Tony Soprano a fuzzy monster?" distraction, but that goes away swiftly as Gandolfini carefully pitches his voice to send like nothing so much as a big, sullen kid. The wild things are almost all sullen kids, really, though it takes Max a long time to realise that: there's Alexander (Paul Dano), who hates that people don't pay attention to him, and Judith (Catherine O'Hara), who has an opinion for everything and gets really angry if she thinks someone is trying to boss her around. Judith has a boyfriend, Ira (Forest Whitaker), who is easy-going and conciliatory to the point of self-abnegation. The closest thing to grown-ups are Douglas (Chris Cooper), who pretty much tolerates the kids with bemusement, and KW (Lauren Ambrose), who has started hanging out with Bob and Terry, who are way smarter and cooler than the things. Carol, who has a crush on KW - or is it that, like Max, he can't stand the loss of his big sister figure? - has grown increasingly short-tempered since Bob and Terry entered the picture, and that's basically what you need to go on. The great bulk of the film - oh, my, how great a bulk it is - consists of the wild things and Max, their newly-anointed king, sitting around and talking about the loss of their uncomplicated happiness, and seeking to find exciting things to do that will make them all a family again. It really is exactly that explicit about what's going on.

Where the Wild Things Are is a film about the psyche of a child, but it would be a tremendous mistake to think that it is a story told from a child's perspective. It is very much a film told from the perspective of an adult remember what it was like to be a child, and it would appear that Jonze and Eggers don't have terribly fond memories of that time of their lives. A more distressingly sad view of what kids go through would be hard to imagine; there's not a single moment where Max does anything fun except that it ends in destruction and misery. To judge from this movie, it's impossible for young people to have any kind of joy in life whatsoever except in fleeting moments, and those moments invariably lead to greater suffering than the pain they were conceived to alleviate.

So, the closest thing I had to a childhood trauma was this one time when I was four, and I got knocked down in a playground and broke my clavicle; maybe if every time I played with my friends somebody died, I'd be in a better position to appreciate what Jonze and Eggers have written here. But damn me to hell if Where the Wild Things Are isn't mostly a suffocating miserabilist for most of its running time - even the "and now Max is safe and home again" coda is a downer in its own way, suggesting that he doesn't get to be an innocent kid anymore. All the joy in the visuals, and all the joy in Sendak's book (which is a much different allegory than the film) are no match for the unending sorrow that the things wear like shrouds. The writers are so eager to work through their demons - and make no mistake, this film could not possibly have been written by men without significant childhood demons - that they either forget or just don't care that being a child can be a lot of fun, too. And while it's all very persychological to think of young people as the seed pods for future adult trauma, the fact that we grown-ups don't like to consider very much is that pre-teen kids are way more resilient than we are. They can bounce back from a hell of a lot; the few that can't grow up to become artistes like Dave Eggers (I should have disclosed ages ago that I really don't like Eggers at all).

And yet (my whole response to the film is one big "and yet"), the fact that Jonze and Eggers are revealing so much of themselves in this emotionally crabbed tribute to the unending hell of childhood is itself reason to see the film. It's thrilling, humiliating, but most of all interesting to see them express something so nakedly as we see in Where the Wild Things Are; not at all comfortable, mind you, but then therapy isn't supposed to be - and make no mistake, more than anything else, Where the Wild Things Are is therapy.

Lastly, I just want to point out the one thing that hugely doesn't work for me on any level: the score, "by Karen O and Carter Burwell". Assuming that Burwell's work consists of the parts that aren't Karen O songs, it's still the most disappointing thing he's done in a whoh my God, he scored Twilight? Never mind what I was saying, but it's still a tediously twee, glittering score that made me want to cut myself, though not as badly as Karen Orzolek's contributions did; but then I've always found her work with the Yeah Yeah Yeahs to typify everything grating about indie rock. Whatever the case, if it's in Where the Wild Things Are and it's musical, it fucking sucks.

6/10

Beginning with what is unabashedly brilliant about the film (not because I want to be nice, but because it's the only thing that's easy to grapple with), it looks as amazing and beautiful as anything else you will see in theatres right now. For a start, the wild things themselves are among the most perfectly-realised fantasy creatures in movie history: a nigh-miraculous marriage of full-body suits made with as much love and attention as anything to ever come out of Jim Henson's Creature Shop and incredibly, almost uncannily expressive CGI facial features, particularly their deep, soulful eyes. It's not hard to understand why young Max would be attracted to these beasts, for they are so warm and full-bodied that one longs to jump into the screen and join in their pile-up right along with him.

Right along side the design of the wild things is the look of their world, courtesy of K.K. Barrett, whose strong work in Jonze's previous features (as well as Sofia Coppola's Marie Antoinette) doesn't even begin to suggest that he had something as imaginative and otherworldly as the giant orbs that make up the things' homes and the vast fort that Max commissions from them. All of these visual splendors are captured by Jonze and his regular cinematographer Lance Acord with a level of sophistication unmatched elsewhere in the careers. Jonze's direction in Being John Malkovich and even more so in Adaptation. always struck me as being deliberately invisible, permitting Charlie Kaufman's hallucinatory screenplays to speak for themselves without being prodded along by funky visuals; to a certain degree he continues that trend in Wild Things, but at the same time the direction is certain and intelligent, keeping us tightly yoked to Max's POV so that the things seem to tower over us in their majesty and terror, and yet when the need arises to bring things to a more intimate scale, he knows exactly when to use a wider shot to bring the creatures and their environment down to a manageable size. Hell, he even manages to make the colossally over-used handheld camera aesthetic that ceased being inventive or appealing years ago seem positively essential. And Acord, well, the film looks beautiful without having to resort to postcard-friendly shots of landscaping; indeed, the way that lighting is used in the film could almost be lovely if it didn't have a certain air of unearthliness to it.

And then, there's the movie as a narrative experience, and well, I just don't know. It's not that I'm bothered with the degree to which it's not Sendak's book. Sendak's book is perfect in a way that no feature film could ever be perfect, since they are not permitted to be so compact. In fact, Jonze and Eggers (they co-wrote, despite the number of reviews that seem to lay all the blame or credit squarely at Eggers's feet) probably have made the most credible adaptation of the slim volume possible, because they have not tried to expand Sendak's tiny scenario into something sprawling; they have used it as the basis for something as personal to themselves as Sendak's book was to him. Therein lies the rub.

The extended plot greatly enlarges the details of Max's home life: with his sister Claire (Pepita Emmerichs) entering the strange world of teenagerdom, his father conspicuously absent save for a somewhat ominous globe bearing the plaque, "This world is yours - Dad", and his mother trying desperately to hold things together at work, keep a good home for her kids, and still pursue a personal life, the boy believes like most children that he isn't getting enough attention, and he acts out violently. In the opening sequence, he gets revenge on his sister's friends by trashing her room; later on he vents his anger at his mom bringing a man to the house (played by Mark Ruffalo in what is not so much a glorified cameo as a featured extra role), by screaming and standing on the kitchen counter threatening to eat her, and biting her on the shoulder - this last event freaks her out so badly that she starts to scream back, and he runs out of the house, and in a fairly delicate transition implied almost solely by the editing, starts to fantasise about taking a boat to a far-away forest on the edge of a desert by the sea, where the wild things are.

The wild things themselves are also expanded, given distinct personalities and voiced by a cast of famous people that, shockingly, don't overwhelm their characters. The most important thing in Max's eyes, since they are the most similar, is Carol (a deliberate echo of Claire, else I'm no judge), the monster whose response to being ignored by those he loves is to lash out with terrible acts of violence. Carol is voiced by James Gandolfini, brilliantly; though at first there's the usual "why is Tony Soprano a fuzzy monster?" distraction, but that goes away swiftly as Gandolfini carefully pitches his voice to send like nothing so much as a big, sullen kid. The wild things are almost all sullen kids, really, though it takes Max a long time to realise that: there's Alexander (Paul Dano), who hates that people don't pay attention to him, and Judith (Catherine O'Hara), who has an opinion for everything and gets really angry if she thinks someone is trying to boss her around. Judith has a boyfriend, Ira (Forest Whitaker), who is easy-going and conciliatory to the point of self-abnegation. The closest thing to grown-ups are Douglas (Chris Cooper), who pretty much tolerates the kids with bemusement, and KW (Lauren Ambrose), who has started hanging out with Bob and Terry, who are way smarter and cooler than the things. Carol, who has a crush on KW - or is it that, like Max, he can't stand the loss of his big sister figure? - has grown increasingly short-tempered since Bob and Terry entered the picture, and that's basically what you need to go on. The great bulk of the film - oh, my, how great a bulk it is - consists of the wild things and Max, their newly-anointed king, sitting around and talking about the loss of their uncomplicated happiness, and seeking to find exciting things to do that will make them all a family again. It really is exactly that explicit about what's going on.

Where the Wild Things Are is a film about the psyche of a child, but it would be a tremendous mistake to think that it is a story told from a child's perspective. It is very much a film told from the perspective of an adult remember what it was like to be a child, and it would appear that Jonze and Eggers don't have terribly fond memories of that time of their lives. A more distressingly sad view of what kids go through would be hard to imagine; there's not a single moment where Max does anything fun except that it ends in destruction and misery. To judge from this movie, it's impossible for young people to have any kind of joy in life whatsoever except in fleeting moments, and those moments invariably lead to greater suffering than the pain they were conceived to alleviate.

So, the closest thing I had to a childhood trauma was this one time when I was four, and I got knocked down in a playground and broke my clavicle; maybe if every time I played with my friends somebody died, I'd be in a better position to appreciate what Jonze and Eggers have written here. But damn me to hell if Where the Wild Things Are isn't mostly a suffocating miserabilist for most of its running time - even the "and now Max is safe and home again" coda is a downer in its own way, suggesting that he doesn't get to be an innocent kid anymore. All the joy in the visuals, and all the joy in Sendak's book (which is a much different allegory than the film) are no match for the unending sorrow that the things wear like shrouds. The writers are so eager to work through their demons - and make no mistake, this film could not possibly have been written by men without significant childhood demons - that they either forget or just don't care that being a child can be a lot of fun, too. And while it's all very persychological to think of young people as the seed pods for future adult trauma, the fact that we grown-ups don't like to consider very much is that pre-teen kids are way more resilient than we are. They can bounce back from a hell of a lot; the few that can't grow up to become artistes like Dave Eggers (I should have disclosed ages ago that I really don't like Eggers at all).

And yet (my whole response to the film is one big "and yet"), the fact that Jonze and Eggers are revealing so much of themselves in this emotionally crabbed tribute to the unending hell of childhood is itself reason to see the film. It's thrilling, humiliating, but most of all interesting to see them express something so nakedly as we see in Where the Wild Things Are; not at all comfortable, mind you, but then therapy isn't supposed to be - and make no mistake, more than anything else, Where the Wild Things Are is therapy.

Lastly, I just want to point out the one thing that hugely doesn't work for me on any level: the score, "by Karen O and Carter Burwell". Assuming that Burwell's work consists of the parts that aren't Karen O songs, it's still the most disappointing thing he's done in a whoh my God, he scored Twilight? Never mind what I was saying, but it's still a tediously twee, glittering score that made me want to cut myself, though not as badly as Karen Orzolek's contributions did; but then I've always found her work with the Yeah Yeah Yeahs to typify everything grating about indie rock. Whatever the case, if it's in Where the Wild Things Are and it's musical, it fucking sucks.

6/10