Disney Animation: Three happy chappies with snappy serapes

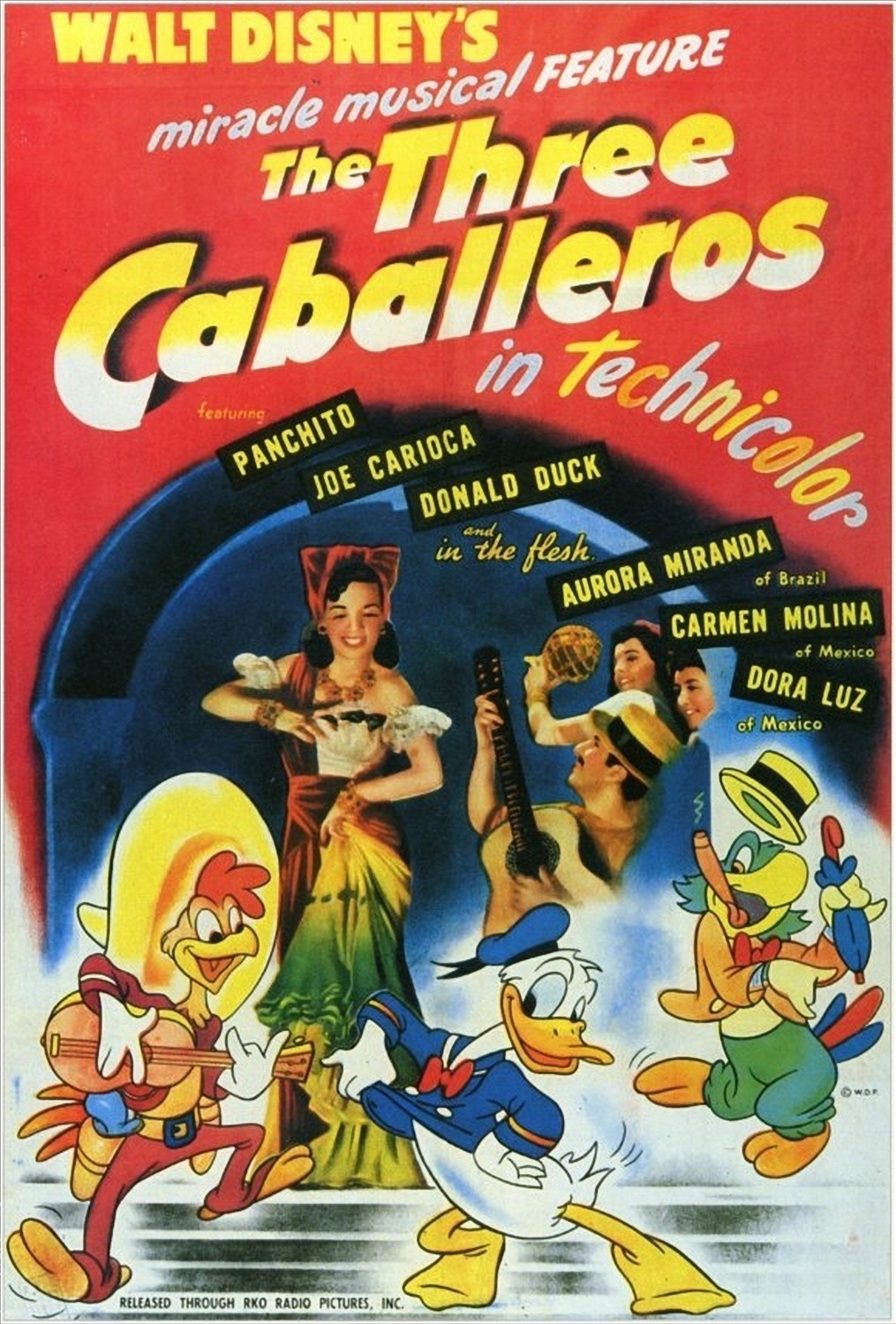

Saludos Amigos was a big enough success that Walt Disney was encouraged to put into production a second Latin American project, again theoretically meant to foster goodwill during the hard days of World War II. This quasi-sequel from 1944, The Three Caballeros (treating upon Brazil once again, along with Mexico in the place of Peru, Chile and Argentina), was a significantly more ambitious production: not just a half-hour longer, it also marked the first time since his silent Alice comedies that Walt oversaw the combination of live action footage with animation, a technology that was only a bit less dodgy than it had been in the '20s. But there's a certain X-factor to it above and beyond such quantifiable thingst; as though, having hacked out what amounted to a quota quickie two years prior, the animators wanted to make something a bit more distinctive and original and, to be frank, absolutely crazed. I would define the different meta-narratives of the two films thusly: the underlying statement of Saludos Amigos is, "Boy, those curious foreigners! Ha ha, they sure do have customs! And they like color! How about that?" while in The Three Caballeros it is more along the lines of, "Peyote buttons? Never heard of 'em, but I guess I'll try a few."

It's the film that Saludos Amigos was supposed to be; it still possesses a rather obnoxiously reductive vision of what Latin American life consists of (exotic animals and sexy women, surrounded by day-glo colors), but on the other hand it's damn entertaining, It also does something that's not altogether unlike its mission statement: showcase the locales and people of Latin America in a manner edifying to people in the U.S. and at the same time promising to the citizenry of the Latin American countries in question that we Yanks would very much like to be their friends. This is largely achieved by having Donald Duck chase after Mexican women constantly for the movie's last 25 minutes, but at least it's not so inane as the preceding movie.

Of all six package movies, The Three Caballeros comes the closest to being a proper narrative, and there are only two shorts that really feel separate from the rest of the work. Here's how it begins: first, are the brightly-colored credits, which I mention largely to notice the odd fact that this is the first Disney feature give credit to its voice cast, although they are not identified by character. Then the film itself begins, on a semi-ominous shot of a large parcel sitting in a featureless void. It would appear that the void is in fact Donald Duck's home, for he soon bounds in, excited to have received such a large bundle, which judging from the tag (which dissolves from Spanish to English before Donald's eyes) is a birthday present from his friends in Latin America (apparently Donald, at least, made good use of the 1941 goodwill tour). The parcel proves to be full of birthday presents, which the duck leaps into with glee; it is a movie projector, and a reel of film titled "Aves Raras" ["Rare Birds"]. It would seem that the film is meant to be a celebration of the wildlife of South America, but the first segment is actually a lengthy tale of Pablo, the cold-blooded penguin, who longed to journey from Antarctica to the Galapagos Islands. Only then comes a brief discussion of some of the birds to be found in the Amazon basin, comically treating on their foibles and physical appearance. Among these many creatures is the strange Aracuan, a bright pink fellow with a baggy shirt and a shock of red hair, who pops right out of the movie to greet Donald.

The film wraps up with the story of a Paraguayan boy who found a flying donkey, and this is effectively the end of the "anthology" portion of The Three Caballeros all that follows will be a more-or-less continuous extension of the framework narrative, divided into episodes of anywhere from a couple minutes to around ten minutes. The flow of these episodes is incredibly surreal - I would not hesitate to call it the most surreal work ever produced by the Disney studios. Donald's next present is a book from Brazil, which opens in a series of pop-up dioramas, one of which has his parrot friend José Carioca puffing away contentedly at a cigar in a café. José is delighted to see Donald, and after their greetings are done, he asks of Donald: "Have you been to Baía?" Donald's negative answer sends José into a reverie, thinking of the unbridled romance of this, the most beautiful city in Brazil (as near as I can tell, they're referring to Salvador, AKA São Salvador da Baía de Todos os Santos, and I can find no reference to it ever being called just plain Baía outside of this movie). His reverie done, he launches into a little samba and clubs Donald with a mallet, shrinking the duck to a size where they can both fit into the train just pulling up into the book. Along their train trip to Baía, the Aracuan pops up to wreak a little havoc, but he doesn't do any lasting harm, and thus do the boys end up in the city at last. There, Donald falls head over heels in love with Aurora Miranda (Carmen's sister), singing a song titled "Os Quindins de Yaya", about selling cookies, which I assume to be a euphemism.

Having failed to make it with Ms. Miranda, Donald and José return to Donald's terrifyingly nihilistic living room, where José shows his friend how to reinflate to normal size and open his last present: a big box from Mexico. Inside is a literal explosion of masks, candy, bits of colorful paper, and pistol-packing rooster named Panchito, who is so hugely thrilled to be with the others that he immediately leads them in song, musically declaring how wonderful it is to be "The Three Caballeros". This done, he presents Donald with a piñata, but before the duck gets a chance to split it open, Panchito describes in short detail one of the Christmas traditions of his country, all of the children of a town going on a mock-pilgrimage in honor of Joseph and the Virgin. Donald doesn't really give a shit, and after some slapsticky business he breaks the piñata, which is full of many delights, but the most delightful is a magical flying sarape that allows Panchito to show Donald and José live-action footage of three Mexican cities. Donald is mostly interested in the live-action girls he spots there, and the other two must bodily restrain him.

There is presumably a scene cut here for content on latter-day video releases, because it seems clear that what happens next is that Donald has too much mescal, and in the skies over Acapulco he begins to hallucinate: a woman sings to him, he sees her face in flowers, José and Panchito keep bursting in and annoying him, cacti dance, and finally, back in his nightmarish, empty home, he pretends that he is a bull and things blow up.

Here's what's craziest about The Three Caballeros: I didn't even mention the most surreal bits in that recap. This is by far the strangest feature-length movie in the history of the Walt Disney Company, with virtually every new minute bringing something more insanely creative than the last to our attention. It doesn't event take the extended framework plot to get there, either. "The Cold-Blooded Penguin" is as peculiar as any short the studio ever produced, with Sterling Holloway narrating in the driest, most ironic tone of voice possible, reminding one of the later work that Edward Everett Horton would do for Jay Ward's "Fractured Fairy Tales"; the short is also an exemplar of the finest in cartoon physics. "The Flying Gauchito", in turn, is an uncharacteristically post-modern stab at storytelling, as the old man recalling his youth keeps stumbling over the details, to the irritation of his younger self.

But the joys of the film are mostly found in the Donald plot, where the animators, apparently chafing to do any damn thing (The Three Caballeros was released in 1944, a year and a half after Bambi and Saludos Amigos were finished), turned off any desire for realism or sensibility and let themselves go wild. The Three Caballeros is the closest that the Disney Studios ever came to the surrealistic anarchy of the Looney Tunes shorts over at Warner Bros. These we have multiple examples of Donald grabbing a beam of light as though it were a tangible object (the latter in the midst of a brilliant comic number where he attempts to replicate José's black magic skills, getting his limbs all tangled up in the process), scenes of José spontaneously dividing into four replicas and having a conversation amongst himself, to say nothing of the ten-minute cavalcade of head movie images years before anyone at Disney is likely to have even heard of LSD. Clearly, this is a film in which a number of gifted artists, freed from the constraints of telling clear stories on classical themes, indulged their playful sides, and it's quite giddy to watch, even as it drags down in some points.

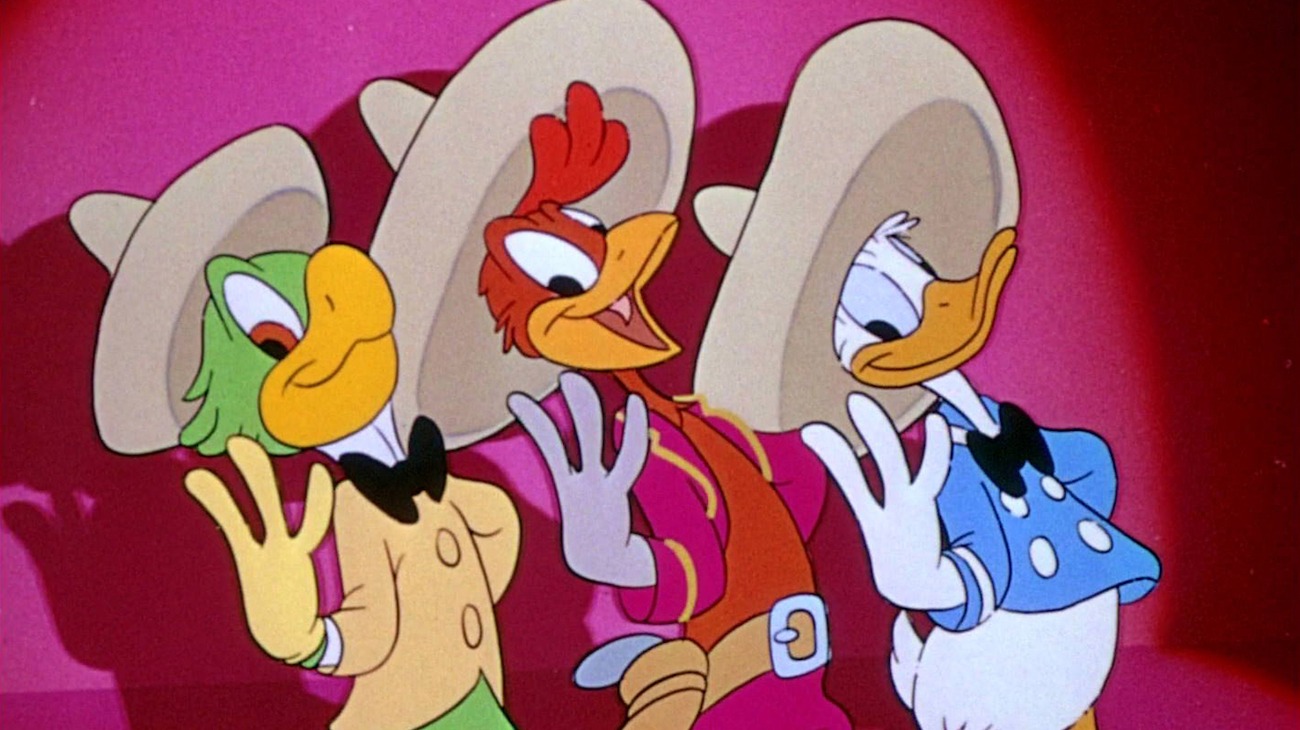

Nowhere is this feeling of "hell with it, let's just be silly" clearer than in the title number, one of the greatest achievements of animator Ward Kimball (who had already supervised Pinocchio's Jiminy Cricket and Dumbo's crows). Kimball was something an animating savant who found "normal" animation a bit too simple for his tastes; his best work ran towards the more stylised, comic, and absurd - his masterwork was the 1953 short Toot, Whistle, Plunk and Boom, the first animated CinemaScope release, and probably the most stylistically unusual thing in Disney Studios history. For "The Three Caballeros", Kimball had been given a free hand, to do whatever he liked; faced with an essentially non-narrative song, he solved the problem it set him by simply putting everything in the lyrics onscreen for the duration of one line. Just to add some humor, he also made certain to keep Donald one step behind Panchito and José, always messing up the dance moves they executed flawlessly. The result is the most imaginative, fun three minutes of Disney animation during the whole fallow period between 1942 and 1950, and arguably one of the most entertaining musical numbers to watch in the company's canon.

About the madness of the Donald Duck sex farce, I can really think of nothing to say: not because it is a sequence unworthy of consideration, but because it's so wholly bizarre as to beggar language. Sexuality is always a weird thing in a Disney movie, but when it's live action women and the most popular animated star of the 1940s, and he's being really, unabashedly horny... it actually makes you feel a little dirty to watch it, I don't mind saying, and not just because of how objectified the women are. Heck, that probably makes it easier to watch. At any rate, in a film full of surrealist touches, Donald the sex fiend is easily the strangest part, though certainly one of the most memorable. (The fact that the animation looks a bit pasted on top of the live action footage just makes it all the weirder).

It's not all silliness and surrealism in the film, mind you: the "Baía" number is nothing but a camera gliding over lovely impressionistic oil backgrounds, for example. And the Christmas sequence - "Las Posadas" - is a series of wonderfully charming still images of little Mexican children out at night, all designed by the whimisical hand of Mary Blair if I know anything about anything at all. By no means is any of this up to the remarkable level of technical achievement found in the pre-war features, but for a film made on the cheap, it's infinitely more attractive than the slipshod Saludos Amigos.

Not to give away the next few reviews or nothing, but this is my favorite of the package films; a chance to see the Disney animators in a rare moment of blissed-out creativity, and the combination of color and sound and character (this film is, I think, the finest moment in Donald Duck's career; certainly his peak after 1935's The Band Concert) makes it as energetic as just about anything else in the Disney canon. Oh, it's clearly not an expensive project that a lot of time had been sunk into; but it has such a loopy appeal that it doesn't necessarily need to be. Given that Disney animation couldn't be too ambitious or exciting in the 1940s, I'm glad the animators were still able to to produce something with this kind of vitality.

It's the film that Saludos Amigos was supposed to be; it still possesses a rather obnoxiously reductive vision of what Latin American life consists of (exotic animals and sexy women, surrounded by day-glo colors), but on the other hand it's damn entertaining, It also does something that's not altogether unlike its mission statement: showcase the locales and people of Latin America in a manner edifying to people in the U.S. and at the same time promising to the citizenry of the Latin American countries in question that we Yanks would very much like to be their friends. This is largely achieved by having Donald Duck chase after Mexican women constantly for the movie's last 25 minutes, but at least it's not so inane as the preceding movie.

Of all six package movies, The Three Caballeros comes the closest to being a proper narrative, and there are only two shorts that really feel separate from the rest of the work. Here's how it begins: first, are the brightly-colored credits, which I mention largely to notice the odd fact that this is the first Disney feature give credit to its voice cast, although they are not identified by character. Then the film itself begins, on a semi-ominous shot of a large parcel sitting in a featureless void. It would appear that the void is in fact Donald Duck's home, for he soon bounds in, excited to have received such a large bundle, which judging from the tag (which dissolves from Spanish to English before Donald's eyes) is a birthday present from his friends in Latin America (apparently Donald, at least, made good use of the 1941 goodwill tour). The parcel proves to be full of birthday presents, which the duck leaps into with glee; it is a movie projector, and a reel of film titled "Aves Raras" ["Rare Birds"]. It would seem that the film is meant to be a celebration of the wildlife of South America, but the first segment is actually a lengthy tale of Pablo, the cold-blooded penguin, who longed to journey from Antarctica to the Galapagos Islands. Only then comes a brief discussion of some of the birds to be found in the Amazon basin, comically treating on their foibles and physical appearance. Among these many creatures is the strange Aracuan, a bright pink fellow with a baggy shirt and a shock of red hair, who pops right out of the movie to greet Donald.

The film wraps up with the story of a Paraguayan boy who found a flying donkey, and this is effectively the end of the "anthology" portion of The Three Caballeros all that follows will be a more-or-less continuous extension of the framework narrative, divided into episodes of anywhere from a couple minutes to around ten minutes. The flow of these episodes is incredibly surreal - I would not hesitate to call it the most surreal work ever produced by the Disney studios. Donald's next present is a book from Brazil, which opens in a series of pop-up dioramas, one of which has his parrot friend José Carioca puffing away contentedly at a cigar in a café. José is delighted to see Donald, and after their greetings are done, he asks of Donald: "Have you been to Baía?" Donald's negative answer sends José into a reverie, thinking of the unbridled romance of this, the most beautiful city in Brazil (as near as I can tell, they're referring to Salvador, AKA São Salvador da Baía de Todos os Santos, and I can find no reference to it ever being called just plain Baía outside of this movie). His reverie done, he launches into a little samba and clubs Donald with a mallet, shrinking the duck to a size where they can both fit into the train just pulling up into the book. Along their train trip to Baía, the Aracuan pops up to wreak a little havoc, but he doesn't do any lasting harm, and thus do the boys end up in the city at last. There, Donald falls head over heels in love with Aurora Miranda (Carmen's sister), singing a song titled "Os Quindins de Yaya", about selling cookies, which I assume to be a euphemism.

Having failed to make it with Ms. Miranda, Donald and José return to Donald's terrifyingly nihilistic living room, where José shows his friend how to reinflate to normal size and open his last present: a big box from Mexico. Inside is a literal explosion of masks, candy, bits of colorful paper, and pistol-packing rooster named Panchito, who is so hugely thrilled to be with the others that he immediately leads them in song, musically declaring how wonderful it is to be "The Three Caballeros". This done, he presents Donald with a piñata, but before the duck gets a chance to split it open, Panchito describes in short detail one of the Christmas traditions of his country, all of the children of a town going on a mock-pilgrimage in honor of Joseph and the Virgin. Donald doesn't really give a shit, and after some slapsticky business he breaks the piñata, which is full of many delights, but the most delightful is a magical flying sarape that allows Panchito to show Donald and José live-action footage of three Mexican cities. Donald is mostly interested in the live-action girls he spots there, and the other two must bodily restrain him.

There is presumably a scene cut here for content on latter-day video releases, because it seems clear that what happens next is that Donald has too much mescal, and in the skies over Acapulco he begins to hallucinate: a woman sings to him, he sees her face in flowers, José and Panchito keep bursting in and annoying him, cacti dance, and finally, back in his nightmarish, empty home, he pretends that he is a bull and things blow up.

Here's what's craziest about The Three Caballeros: I didn't even mention the most surreal bits in that recap. This is by far the strangest feature-length movie in the history of the Walt Disney Company, with virtually every new minute bringing something more insanely creative than the last to our attention. It doesn't event take the extended framework plot to get there, either. "The Cold-Blooded Penguin" is as peculiar as any short the studio ever produced, with Sterling Holloway narrating in the driest, most ironic tone of voice possible, reminding one of the later work that Edward Everett Horton would do for Jay Ward's "Fractured Fairy Tales"; the short is also an exemplar of the finest in cartoon physics. "The Flying Gauchito", in turn, is an uncharacteristically post-modern stab at storytelling, as the old man recalling his youth keeps stumbling over the details, to the irritation of his younger self.

But the joys of the film are mostly found in the Donald plot, where the animators, apparently chafing to do any damn thing (The Three Caballeros was released in 1944, a year and a half after Bambi and Saludos Amigos were finished), turned off any desire for realism or sensibility and let themselves go wild. The Three Caballeros is the closest that the Disney Studios ever came to the surrealistic anarchy of the Looney Tunes shorts over at Warner Bros. These we have multiple examples of Donald grabbing a beam of light as though it were a tangible object (the latter in the midst of a brilliant comic number where he attempts to replicate José's black magic skills, getting his limbs all tangled up in the process), scenes of José spontaneously dividing into four replicas and having a conversation amongst himself, to say nothing of the ten-minute cavalcade of head movie images years before anyone at Disney is likely to have even heard of LSD. Clearly, this is a film in which a number of gifted artists, freed from the constraints of telling clear stories on classical themes, indulged their playful sides, and it's quite giddy to watch, even as it drags down in some points.

Nowhere is this feeling of "hell with it, let's just be silly" clearer than in the title number, one of the greatest achievements of animator Ward Kimball (who had already supervised Pinocchio's Jiminy Cricket and Dumbo's crows). Kimball was something an animating savant who found "normal" animation a bit too simple for his tastes; his best work ran towards the more stylised, comic, and absurd - his masterwork was the 1953 short Toot, Whistle, Plunk and Boom, the first animated CinemaScope release, and probably the most stylistically unusual thing in Disney Studios history. For "The Three Caballeros", Kimball had been given a free hand, to do whatever he liked; faced with an essentially non-narrative song, he solved the problem it set him by simply putting everything in the lyrics onscreen for the duration of one line. Just to add some humor, he also made certain to keep Donald one step behind Panchito and José, always messing up the dance moves they executed flawlessly. The result is the most imaginative, fun three minutes of Disney animation during the whole fallow period between 1942 and 1950, and arguably one of the most entertaining musical numbers to watch in the company's canon.

About the madness of the Donald Duck sex farce, I can really think of nothing to say: not because it is a sequence unworthy of consideration, but because it's so wholly bizarre as to beggar language. Sexuality is always a weird thing in a Disney movie, but when it's live action women and the most popular animated star of the 1940s, and he's being really, unabashedly horny... it actually makes you feel a little dirty to watch it, I don't mind saying, and not just because of how objectified the women are. Heck, that probably makes it easier to watch. At any rate, in a film full of surrealist touches, Donald the sex fiend is easily the strangest part, though certainly one of the most memorable. (The fact that the animation looks a bit pasted on top of the live action footage just makes it all the weirder).

It's not all silliness and surrealism in the film, mind you: the "Baía" number is nothing but a camera gliding over lovely impressionistic oil backgrounds, for example. And the Christmas sequence - "Las Posadas" - is a series of wonderfully charming still images of little Mexican children out at night, all designed by the whimisical hand of Mary Blair if I know anything about anything at all. By no means is any of this up to the remarkable level of technical achievement found in the pre-war features, but for a film made on the cheap, it's infinitely more attractive than the slipshod Saludos Amigos.

Not to give away the next few reviews or nothing, but this is my favorite of the package films; a chance to see the Disney animators in a rare moment of blissed-out creativity, and the combination of color and sound and character (this film is, I think, the finest moment in Donald Duck's career; certainly his peak after 1935's The Band Concert) makes it as energetic as just about anything else in the Disney canon. Oh, it's clearly not an expensive project that a lot of time had been sunk into; but it has such a loopy appeal that it doesn't necessarily need to be. Given that Disney animation couldn't be too ambitious or exciting in the 1940s, I'm glad the animators were still able to to produce something with this kind of vitality.

Categories: animation, anthology films, disney, documentaries, musicals, the cinema of wwii