Disney Animation: Music will play the shadows away

It is a known thing that Walt Disney took the failure of Fantasia badly, and on a rather personal level. The film that was to have been the culmination of his artistic ambitions become a well-reviewed box-office meltdown, and if the studio never again came even close to making such a self-consciously artsy movie again, I think it is because the cuts that the producer received in those fateful days late in 1940 and early in 1941 never really healed.

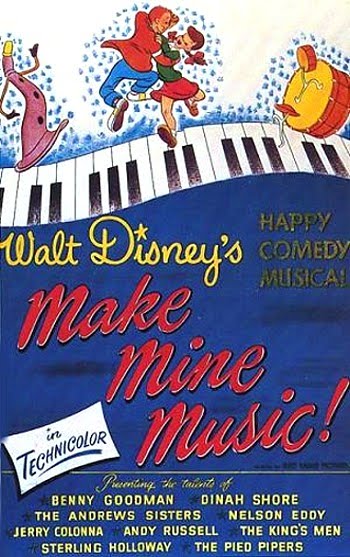

In the midst of Disney's run of package films in the 1940s, two films were released that were both modeled explicitly after Fantasia, though with modern pop music instead of classic pieces, far less expansive running times, and much simpler animation. I do not know if this was Walt's attempt to prove that his basic idea of a non-narrative program of music and animation was sound, a bitter reproach to the philistines who couldn't appreciate his visionary genius for what it was, or if in fact Walt had nothing to do with these films at all, and had locked himself away to brood over the direction his fate had gone over the last few years. At any rate, Make Mine Music, the first of the two "Poor Man's Fantasias" as they are often called, is one of the saddest little orphans in the whole of the Disney animated features canon. It couldn't even turn a profit during its single theatrical release - proving, if nothing else, that the whole "music + animated shorts = feature" probably wasn't something that Disney should keep pursuing, and its lonely place in history was cemented when it became the very last Disney vault title to ever see release on home video (it debuted on VHS and DVD in June, 2000; Saludos Amigos beat it by just about one month).

Though the film hits more than it misses over the course of its ten sequences - and one of the hits is among the best of the many shorts that the studio released in that decade - it's not hard to understand why the film was ignored and then forgotten. It suffers from a general lack of affect that was becoming a significant source of evil at the Disney Studios in the immediate post-war years: constantly scrabbling for money, lost without the guiding hand of Walt, who by all accounts had spent most of his energy devising exciting propaganda films and somewhat lost interest in animation once the money to do the things he wanted had dried up.

In short, this was a period of transition for Disney, and much like the twenty-year interregnum following Walt's death in 1966, the studio was caught in an identity crisis that threatened to destroy it altogether. Financially, the only thing that was keeping the studio afloat were re-issues of older movies: Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs in 1944, followed by Pinocchio in 1945 (Fantasia would once again flop when it was re-released in 1946). The war years had seen a second live-action documentary incorporating animated sequences, the propaganda effort Victory Through Air Power, to sit alongside The Reluctant Dragon; the idea that live-action might be a valid future direction for the studio to go was reinforced by the production of Song of the South, a hybrid film refining the technology developed for The Three Caballeros. It was this project that received most of Walt's attention, while Make Mine Music languished in the animation department, and it far out-grossed its little cousin in the 1946 box office charts, despite or because of igniting a race controversy that remains alive to this day. Song of the South's success spurred the creation of more and more live-action movies, forcing Disney animation deeper into its shell as the decade progressed.

So much for the history lesson. Let us now take a look at this sorry little thing, this Make Mine Music that got put together despite the fact that nobody much cared for it, yet which still found the animators - all of them the same greatly talented craftsmen who'd given so much to the masterpieces of the early years of the '40s - trying in small ways to extend the limits of their art.

Like Fantasia, which included everything from an abstract Baroque piece to instantly familiar and comfortable symphonic pieces to nervy modernism, Make Mine Music is deliberately pitched as a survey of many different genres popular at the time: ballads and jazz, opera and pop. And like Fantasia, the conceit is that we're attending a concert of sorts, taking place in a lovely Art Deco skyscraper that's revealed in the opening credits - and it doesn't speak terribly well of the film that some of the most well-drawn material in the film is the credit sequence, but it's too early to bitch about that.

The first of the ten numbers finds The King's Men, a bluegrass group, singing the story of "The Martins and the Coys", a tale of two feuding Appalachian families modeled after the Hatfields and the McCoys. This sequence was snipped from the DVD release of the film, and there is some conflict as to why: there are those who tell you it's because of the gun violence - very nearly the first thing that happens is that both families die in a hail of bullets, though of course we don't actually see the deaths, only their angels rising up cartoon-style - or because it insulting to the rural mountain dwellers of the Appalachians. Frankly, I'd prefer it be the latter, if only because that at least fits in with the bullshit political correctness that still keeps Song of the South from home video, even in a scholarly edition; the caricatures are pretty dumbfounding, though no worse than much of what you can find in the animation of Disney and other studios in that period.

At any rate, the sequence quickly turns into a cutesy romance about the last Martin and the last Coy falling in love, only to have their own domestic squabbles far outstrip any of the rancor between their two families. It's a faintly amusing comic piece, and it's pretty well-animated, all things considered; it opens with an ambitious multiplane camera shot that seems far more complex than the package films' low budgets would ordinarily permit. But it offers little that isn't found in any of the stand-alone Disney comic shorts of the period, and it's a distinctly pokey way to start things off. The song is especially irritating to modern ears, which helps not at all.

Next up, the Ken Darby Singers perform "Blue Bayou", the most curious piece in the whole feature, for it consists of footage first animated for Fantasia, when it was to have been accompanied by Claude Debussy's Suite Bergamasque, or Clair de lune. It was inked and painted a year after Fantasia tanked, meant to be released as a short, but it was shelved, and only now, after being significantly recut, did it find its way to the public eye, yoked to a pleasant but unforgivably drowsy ballad.

It's obvious that "Blue Bayou" was animated when money was much freer than it had become in 1946: it's the most detailed and painterly of all the shorts in Make Mine Music. Just like the label says, it depicts a bayou, and it is blue, in the light of a full moon. It looks not unlike a moving oil painting, and the animation of a heron at one point is a particularly lovely touch, and when all is said and done it cannot be denied that this is the most visually accomplished part of the feature; but there's no getting around that damn song, which is so sleepy that it makes you want to close your eyes and drift far, far away from the movie. Here we see the first occurrence of a problem that virtually overwhelms Make Mine Music: it shifts tones too abruptly to ever develop a reasonable flow, and so it hangs together less successfully than any of the other package films.

Case in point: the very next number is a bouncy jazz number performed by Benny Goodman and his band. Called "All the Cats Join In", it's one of the few unqualified successes of the feature, although it helps to have a high tolerance for '40s jazz-pop. The narrative is simple: a teen boy is alone at the soda shop, and he wants some friends to help him swing, or jive, or whatever verb you used in the '40s to mean "dance to poppy, white-friendly jazz". So he calls up his girl, and picks her up in his car, and they grab a bunch of friends (or "cats" in the teenage vernacular of those days) and get to dancing. The song comments mindlessly on this action: "Down goes my last two bits / Comes up one banana split / And all the cats join in".

What makes this supremely interesting is the animation style, unlike anything else in Disney at the time: full of round, somewhat expressionless and mostly anonymous characters, against a background of the most barbarically simple line drawings. And not just line drawings, but drawings that are drawn right before our eyes, by an animated pencil working hectically to keep up with the high-pitched energy of the song (it fails, at one point, and a boy falls to the ground when his stool doesn't appear in time). It was the second time the Disney animators had used that trick, after the final sequence in Saludos Amigos, beating Chuck Jones's epochal Warner short Duck Amuck by still seven years (though, of course, not bettering it).

None of it is a timeless example of graphic art, but as a depiction of what the '40s looked like in the '40s, it's an amusing time capsule that still entertains in its own right, and it gets extra points for indicating, in a roundabout way, that women are naked under their clothes - I don't mean to sound pervy all the time, but when sex accidentally finds its way into a Disney film, it's worth mentioning it, for it is rare. And "All the Cats Join In" thankfully acknowledges that even in its sanitised, Benny Goodman form, jazz is about having sex.

The tone shifts back into the sleepy in "Without You", sung by Andy Russell. This is perhaps the most pointless bit of animation ever created for a Disney production: nothing but dull backgrounds that get some interesting effects animation thrown at them, most of it watery in nature. The song is inordinately soporific, and the best and only justification I can come up with for what is thankfully the shortest piece in Make Mine Music is that it makes a good demo reel for how the Disney animators could replicate the optical effects of looking at still images through moving water.

The next number, bringing us halfway through, is "Casey at the Bat", a recitation of the 1888 poem of the tragedy of losing a baseball game, performed by Bob Hope's sidekick Jerry Colonna. I am at a loss to explain what music is being made mine, or anybody else's; this is a dramatic reading by a man using a comic Irish accent, with a score beneath it, but to call it a "song" bends the definition of that word a bit far beyond. Leaving that aside: one of the three longest sequences in the film, it's also one of the two most famous, though I do not personally consider it one of the very best shorts here, largely because of Colonna's indulgent line readings. But it is certainly a funny enough piece, animated more according to the Warner Bros. style of crazy physics and exaggerated physical performance than what we'd usually expect to see from a routine Disney piece. I suspect that, as in The Three Caballeros, the animators were simply trying on a new style to keep themselves amused. And lo! it is amusing. To describe it too fully is to break the joke, but for the sheer spectacle of Looney Tunes physics and Disney character design being mashed together, it is of more than incidental interest for the dedicated 1940s animation scholar.

The second half begins with "Two Silhouettes", another slow segment. This one is sung by Dinah Shore, one of the most popular singers of her era, and danced by the Russian ballet team of David Lichine and Tatiana Riabouchinska. It is a lovely and delicate thing, though the rotoscoping used to capture the dancers as the silhouettes of the title has not aged as well as some of the other tricks used by the Disney animators throughout the years. As with all of the slow numbers, it bogs down a little, but it is pretty, with nicely expressive use of color to evoke silhouettes in love. Still, you can just tell that the artists weren't stretching with this one, at all.

Next, we have the great masterpiece of Make Mine Music: Sergei Prokofiev's Peter and the Wolf, as narrated by Sterling Holloway, well on his way to becoming one of the indispensable Disney voice artists. The short was good enough to accompany the subsequent theatrical re-release of Fantasia, and despite the bubbly comic tone (and the musical simplicity of the composition), it surely fits with that film better than the poppy feature that it was created for.

The story has been Disneyfied a bit; the characters given names, the duck remains un-eaten. But in the main this is a wholly successful version of Prokofiev's classic children's music. It has a charmingly cartoonish appreciation of Russian culture and language, which I think to be a holdover from the war, Holloway's narration is about as close to perfection as any other English narrator of the piece has ever managed (though I remain enamored of Leonard Bernstein's recording), and the character design is, while quite simple, round and appealing in the way of the best American cartoons (Peter, I mention for no reason, looks a lot like the young hero of "The Flying Gauchito" from The Three Caballeros, with different hair).

The one glowing exception is the wolf itself. A triumph of design and animation wasted on a forgotten feature like this, the wolf is one of the great Disney villains, period. With fiery yellow eyes and a long snout of giant teeth, he's one of the most genuinely scary creations the animators ever put to celluloid, more a hellbeast than an animal, and his movements suggest a weight that his skinny frame doesn't appear to possess, giving him an extra dash of otherworldliness. If there was not a single thing to recommend Make Mine Music but the wolf, I would still not be prepared to throw the whole thing out. That much do I find this character a work of great artistry.

"After You've Gone" is a fun noodling about, but, especially after "Peter and the Wolf", it has all the significance of a glass of water meant to cleanse the palate. Another Benny Goodman song, this one instrumental, the number is basically like Fantasia's "Toccata and Fugue", an attempt to dramatise the act of listening to music, which here means jazz instruments running around and morphing into other things. It is pleasant, forgettable, and boasts some fun, bright colors - that is all.

The Andrews Sisters, a group that I have never been able to stand, follow with "Johnny Fedora and Alice Blue Bonnett" (Edith Piaf peformed it in the French dub, lucky damn bastard French). It's a cute love story, about two hats that fall in love in a store window, but when she is sold he spends the next several - months? years? - looking for her. Aside from the fact that I don't like the music, the big problem I have with this sequence is the character design: maybe it is possible to make anthropomorphic hats that aren't a bit disgusting to look at, but that has not been achieved here, particularly with Johnny, whose mouth is formed by the broad area that a man's head goes in. I remember being freaked out when I saw this on one Disney TV show or another (with "Casey" and "Peter", this is the most frequently anthologised segment from Make Mine Music), so maybe this is just a childhood trauma thing speaking. At any rate, I cannot fault the nice development of the story, nor the animation quality. The best part of all are the backgrounds, colored with a technique I cannot readily name, but in some sequences it looks like chalk.

The finale is "The Whale Who Wanted to Sing At the Met", a short "about" music more than it is a musical short. The title explains most of it: Willie, a sperm whale that can sing opera in tenor, baritone and bass voices, wants to get his big break, but the impresario Tetti Tatti assumes that the whale has swallowed a trio of opera singers, and mounts an expedition to get them back out, by killing Willie. In no small part, the piece is a showcase for the skills of Nelson Eddy, once the highest-paid singer in the world, and a huge crossover star between the spheres of high opera and Hollywood musicals. He sings everything in four (or five?) different ranges, as well as acting multiple characters, and though I have little use for the overly flowery style that characterised much of opera singing in the first half of the 20th Century, I must concede that what Eddy did in this film was quite amazing.

By and large, this last sequence is more interesting in the concept than the execution: although Willie himself is a well-animated character, with no qualification, and there is a moment where he plays Méphistophélès in Gounod's Faust that is one of the damn cutest things in any of the package films. All the same, the story just doesn't hold together much at all, and the piece can't support its running time, or its out-of-left-field tragic ending.

In other words, it makes a fairly appropriate conclusion for Make Mine Music: it is so close to good in enough ways that you might as well just call it worthwhile, but it has a tremendous lack of direction, and it wobbles badly in tone. Thus ends one of the most sweetly inept attempts to make a feature film in Disney animated history. Part of me really likes the film; the much greater remainder of me is annoyed and saddened by its bumbling awkwardness. Thankfully, the next stab at a poor man's Fantasia, though still no masterpiece, would turn out far better.

In the midst of Disney's run of package films in the 1940s, two films were released that were both modeled explicitly after Fantasia, though with modern pop music instead of classic pieces, far less expansive running times, and much simpler animation. I do not know if this was Walt's attempt to prove that his basic idea of a non-narrative program of music and animation was sound, a bitter reproach to the philistines who couldn't appreciate his visionary genius for what it was, or if in fact Walt had nothing to do with these films at all, and had locked himself away to brood over the direction his fate had gone over the last few years. At any rate, Make Mine Music, the first of the two "Poor Man's Fantasias" as they are often called, is one of the saddest little orphans in the whole of the Disney animated features canon. It couldn't even turn a profit during its single theatrical release - proving, if nothing else, that the whole "music + animated shorts = feature" probably wasn't something that Disney should keep pursuing, and its lonely place in history was cemented when it became the very last Disney vault title to ever see release on home video (it debuted on VHS and DVD in June, 2000; Saludos Amigos beat it by just about one month).

Though the film hits more than it misses over the course of its ten sequences - and one of the hits is among the best of the many shorts that the studio released in that decade - it's not hard to understand why the film was ignored and then forgotten. It suffers from a general lack of affect that was becoming a significant source of evil at the Disney Studios in the immediate post-war years: constantly scrabbling for money, lost without the guiding hand of Walt, who by all accounts had spent most of his energy devising exciting propaganda films and somewhat lost interest in animation once the money to do the things he wanted had dried up.

In short, this was a period of transition for Disney, and much like the twenty-year interregnum following Walt's death in 1966, the studio was caught in an identity crisis that threatened to destroy it altogether. Financially, the only thing that was keeping the studio afloat were re-issues of older movies: Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs in 1944, followed by Pinocchio in 1945 (Fantasia would once again flop when it was re-released in 1946). The war years had seen a second live-action documentary incorporating animated sequences, the propaganda effort Victory Through Air Power, to sit alongside The Reluctant Dragon; the idea that live-action might be a valid future direction for the studio to go was reinforced by the production of Song of the South, a hybrid film refining the technology developed for The Three Caballeros. It was this project that received most of Walt's attention, while Make Mine Music languished in the animation department, and it far out-grossed its little cousin in the 1946 box office charts, despite or because of igniting a race controversy that remains alive to this day. Song of the South's success spurred the creation of more and more live-action movies, forcing Disney animation deeper into its shell as the decade progressed.

So much for the history lesson. Let us now take a look at this sorry little thing, this Make Mine Music that got put together despite the fact that nobody much cared for it, yet which still found the animators - all of them the same greatly talented craftsmen who'd given so much to the masterpieces of the early years of the '40s - trying in small ways to extend the limits of their art.

Like Fantasia, which included everything from an abstract Baroque piece to instantly familiar and comfortable symphonic pieces to nervy modernism, Make Mine Music is deliberately pitched as a survey of many different genres popular at the time: ballads and jazz, opera and pop. And like Fantasia, the conceit is that we're attending a concert of sorts, taking place in a lovely Art Deco skyscraper that's revealed in the opening credits - and it doesn't speak terribly well of the film that some of the most well-drawn material in the film is the credit sequence, but it's too early to bitch about that.

The first of the ten numbers finds The King's Men, a bluegrass group, singing the story of "The Martins and the Coys", a tale of two feuding Appalachian families modeled after the Hatfields and the McCoys. This sequence was snipped from the DVD release of the film, and there is some conflict as to why: there are those who tell you it's because of the gun violence - very nearly the first thing that happens is that both families die in a hail of bullets, though of course we don't actually see the deaths, only their angels rising up cartoon-style - or because it insulting to the rural mountain dwellers of the Appalachians. Frankly, I'd prefer it be the latter, if only because that at least fits in with the bullshit political correctness that still keeps Song of the South from home video, even in a scholarly edition; the caricatures are pretty dumbfounding, though no worse than much of what you can find in the animation of Disney and other studios in that period.

At any rate, the sequence quickly turns into a cutesy romance about the last Martin and the last Coy falling in love, only to have their own domestic squabbles far outstrip any of the rancor between their two families. It's a faintly amusing comic piece, and it's pretty well-animated, all things considered; it opens with an ambitious multiplane camera shot that seems far more complex than the package films' low budgets would ordinarily permit. But it offers little that isn't found in any of the stand-alone Disney comic shorts of the period, and it's a distinctly pokey way to start things off. The song is especially irritating to modern ears, which helps not at all.

Next up, the Ken Darby Singers perform "Blue Bayou", the most curious piece in the whole feature, for it consists of footage first animated for Fantasia, when it was to have been accompanied by Claude Debussy's Suite Bergamasque, or Clair de lune. It was inked and painted a year after Fantasia tanked, meant to be released as a short, but it was shelved, and only now, after being significantly recut, did it find its way to the public eye, yoked to a pleasant but unforgivably drowsy ballad.

It's obvious that "Blue Bayou" was animated when money was much freer than it had become in 1946: it's the most detailed and painterly of all the shorts in Make Mine Music. Just like the label says, it depicts a bayou, and it is blue, in the light of a full moon. It looks not unlike a moving oil painting, and the animation of a heron at one point is a particularly lovely touch, and when all is said and done it cannot be denied that this is the most visually accomplished part of the feature; but there's no getting around that damn song, which is so sleepy that it makes you want to close your eyes and drift far, far away from the movie. Here we see the first occurrence of a problem that virtually overwhelms Make Mine Music: it shifts tones too abruptly to ever develop a reasonable flow, and so it hangs together less successfully than any of the other package films.

Case in point: the very next number is a bouncy jazz number performed by Benny Goodman and his band. Called "All the Cats Join In", it's one of the few unqualified successes of the feature, although it helps to have a high tolerance for '40s jazz-pop. The narrative is simple: a teen boy is alone at the soda shop, and he wants some friends to help him swing, or jive, or whatever verb you used in the '40s to mean "dance to poppy, white-friendly jazz". So he calls up his girl, and picks her up in his car, and they grab a bunch of friends (or "cats" in the teenage vernacular of those days) and get to dancing. The song comments mindlessly on this action: "Down goes my last two bits / Comes up one banana split / And all the cats join in".

What makes this supremely interesting is the animation style, unlike anything else in Disney at the time: full of round, somewhat expressionless and mostly anonymous characters, against a background of the most barbarically simple line drawings. And not just line drawings, but drawings that are drawn right before our eyes, by an animated pencil working hectically to keep up with the high-pitched energy of the song (it fails, at one point, and a boy falls to the ground when his stool doesn't appear in time). It was the second time the Disney animators had used that trick, after the final sequence in Saludos Amigos, beating Chuck Jones's epochal Warner short Duck Amuck by still seven years (though, of course, not bettering it).

None of it is a timeless example of graphic art, but as a depiction of what the '40s looked like in the '40s, it's an amusing time capsule that still entertains in its own right, and it gets extra points for indicating, in a roundabout way, that women are naked under their clothes - I don't mean to sound pervy all the time, but when sex accidentally finds its way into a Disney film, it's worth mentioning it, for it is rare. And "All the Cats Join In" thankfully acknowledges that even in its sanitised, Benny Goodman form, jazz is about having sex.

The tone shifts back into the sleepy in "Without You", sung by Andy Russell. This is perhaps the most pointless bit of animation ever created for a Disney production: nothing but dull backgrounds that get some interesting effects animation thrown at them, most of it watery in nature. The song is inordinately soporific, and the best and only justification I can come up with for what is thankfully the shortest piece in Make Mine Music is that it makes a good demo reel for how the Disney animators could replicate the optical effects of looking at still images through moving water.

The next number, bringing us halfway through, is "Casey at the Bat", a recitation of the 1888 poem of the tragedy of losing a baseball game, performed by Bob Hope's sidekick Jerry Colonna. I am at a loss to explain what music is being made mine, or anybody else's; this is a dramatic reading by a man using a comic Irish accent, with a score beneath it, but to call it a "song" bends the definition of that word a bit far beyond. Leaving that aside: one of the three longest sequences in the film, it's also one of the two most famous, though I do not personally consider it one of the very best shorts here, largely because of Colonna's indulgent line readings. But it is certainly a funny enough piece, animated more according to the Warner Bros. style of crazy physics and exaggerated physical performance than what we'd usually expect to see from a routine Disney piece. I suspect that, as in The Three Caballeros, the animators were simply trying on a new style to keep themselves amused. And lo! it is amusing. To describe it too fully is to break the joke, but for the sheer spectacle of Looney Tunes physics and Disney character design being mashed together, it is of more than incidental interest for the dedicated 1940s animation scholar.

The second half begins with "Two Silhouettes", another slow segment. This one is sung by Dinah Shore, one of the most popular singers of her era, and danced by the Russian ballet team of David Lichine and Tatiana Riabouchinska. It is a lovely and delicate thing, though the rotoscoping used to capture the dancers as the silhouettes of the title has not aged as well as some of the other tricks used by the Disney animators throughout the years. As with all of the slow numbers, it bogs down a little, but it is pretty, with nicely expressive use of color to evoke silhouettes in love. Still, you can just tell that the artists weren't stretching with this one, at all.

Next, we have the great masterpiece of Make Mine Music: Sergei Prokofiev's Peter and the Wolf, as narrated by Sterling Holloway, well on his way to becoming one of the indispensable Disney voice artists. The short was good enough to accompany the subsequent theatrical re-release of Fantasia, and despite the bubbly comic tone (and the musical simplicity of the composition), it surely fits with that film better than the poppy feature that it was created for.

The story has been Disneyfied a bit; the characters given names, the duck remains un-eaten. But in the main this is a wholly successful version of Prokofiev's classic children's music. It has a charmingly cartoonish appreciation of Russian culture and language, which I think to be a holdover from the war, Holloway's narration is about as close to perfection as any other English narrator of the piece has ever managed (though I remain enamored of Leonard Bernstein's recording), and the character design is, while quite simple, round and appealing in the way of the best American cartoons (Peter, I mention for no reason, looks a lot like the young hero of "The Flying Gauchito" from The Three Caballeros, with different hair).

The one glowing exception is the wolf itself. A triumph of design and animation wasted on a forgotten feature like this, the wolf is one of the great Disney villains, period. With fiery yellow eyes and a long snout of giant teeth, he's one of the most genuinely scary creations the animators ever put to celluloid, more a hellbeast than an animal, and his movements suggest a weight that his skinny frame doesn't appear to possess, giving him an extra dash of otherworldliness. If there was not a single thing to recommend Make Mine Music but the wolf, I would still not be prepared to throw the whole thing out. That much do I find this character a work of great artistry.

"After You've Gone" is a fun noodling about, but, especially after "Peter and the Wolf", it has all the significance of a glass of water meant to cleanse the palate. Another Benny Goodman song, this one instrumental, the number is basically like Fantasia's "Toccata and Fugue", an attempt to dramatise the act of listening to music, which here means jazz instruments running around and morphing into other things. It is pleasant, forgettable, and boasts some fun, bright colors - that is all.

The Andrews Sisters, a group that I have never been able to stand, follow with "Johnny Fedora and Alice Blue Bonnett" (Edith Piaf peformed it in the French dub, lucky damn bastard French). It's a cute love story, about two hats that fall in love in a store window, but when she is sold he spends the next several - months? years? - looking for her. Aside from the fact that I don't like the music, the big problem I have with this sequence is the character design: maybe it is possible to make anthropomorphic hats that aren't a bit disgusting to look at, but that has not been achieved here, particularly with Johnny, whose mouth is formed by the broad area that a man's head goes in. I remember being freaked out when I saw this on one Disney TV show or another (with "Casey" and "Peter", this is the most frequently anthologised segment from Make Mine Music), so maybe this is just a childhood trauma thing speaking. At any rate, I cannot fault the nice development of the story, nor the animation quality. The best part of all are the backgrounds, colored with a technique I cannot readily name, but in some sequences it looks like chalk.

The finale is "The Whale Who Wanted to Sing At the Met", a short "about" music more than it is a musical short. The title explains most of it: Willie, a sperm whale that can sing opera in tenor, baritone and bass voices, wants to get his big break, but the impresario Tetti Tatti assumes that the whale has swallowed a trio of opera singers, and mounts an expedition to get them back out, by killing Willie. In no small part, the piece is a showcase for the skills of Nelson Eddy, once the highest-paid singer in the world, and a huge crossover star between the spheres of high opera and Hollywood musicals. He sings everything in four (or five?) different ranges, as well as acting multiple characters, and though I have little use for the overly flowery style that characterised much of opera singing in the first half of the 20th Century, I must concede that what Eddy did in this film was quite amazing.

By and large, this last sequence is more interesting in the concept than the execution: although Willie himself is a well-animated character, with no qualification, and there is a moment where he plays Méphistophélès in Gounod's Faust that is one of the damn cutest things in any of the package films. All the same, the story just doesn't hold together much at all, and the piece can't support its running time, or its out-of-left-field tragic ending.

In other words, it makes a fairly appropriate conclusion for Make Mine Music: it is so close to good in enough ways that you might as well just call it worthwhile, but it has a tremendous lack of direction, and it wobbles badly in tone. Thus ends one of the most sweetly inept attempts to make a feature film in Disney animated history. Part of me really likes the film; the much greater remainder of me is annoyed and saddened by its bumbling awkwardness. Thankfully, the next stab at a poor man's Fantasia, though still no masterpiece, would turn out far better.

Categories: animation, anthology films, disney, musicals, post-war hollywood