The films of Alan J. Pakula

If I have dragged my feet in this Alan J. Pakula retrospective, it is because I knew what lay in wait, and I wanted to stave off my fate as long as I possibly could. For even if the director managed to delay his arrival in the 1980s by the length of one film when he made the curious political thriller Rollover, we all owe God a death, and Pakula paid his with the leaden 1982 prestige drama Sophie's Choice, a ponderous, horribly mirthless affair that typifies everything that made the 1980s such a lousy decade for American drama. This much, I could stand to re-watch, in the name of scholarship, if Sophie's Choice were not also a suffocating 151 minutes long, with a healthy portion of that running time devoted to a hunk of Holocausploitation of the most crass and cynical variety. And that's the good part.

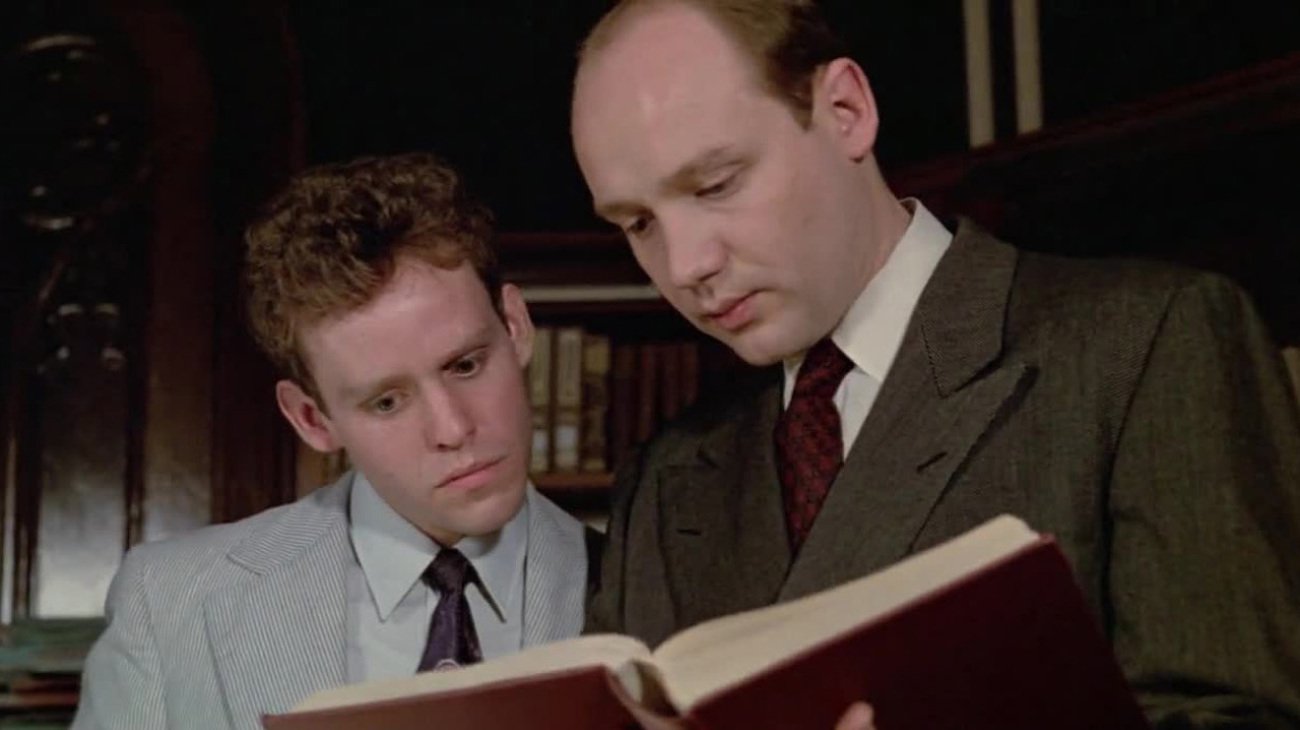

If you had only heard of the film, but not seen it, and I asked you to summarise what you know about it, I think you would almost certainly give an answer along the lines of "Meryl Streep has to choose one of her children to give up to the Nazis". So close, but no, that's not it. Technically, yes, I suppose you could describe it that way, much as you could describe Casablanca as "a night club owner shoots a Nazi major." Yes, it does happen in the film - that's exactly the choice mentioned in the title. But it's not at all what Sophie's Choice is "about". It's rather about a callow young Southerner named Stingo (Peter MacNicol) who travels to Brooklyn in the summer of 1947 to find himself as a writer, and falls in with a most peculiar couple that lives above him in a boarding house: Sophie Zawistowski (Streep), a Polish Catholic who survived the camp at Auschwitz-Birkenau, and Nathan Landau (Kevin Kline), a New York Jew who rescued her from anemia when she was still wasting from the traumas she suffered under the Germans. The first time Stingo sees either of these characters, it's when they're in the middle of a vicious fight on the stairs right outside his room; less than twenty-hour hours later they've made up and invited the boy to join in their free-spirited life as their new best friend. Innocent and anxious to discover the colorful New York freedom of spirit that he came north to find, Stingo happily jumps into their lives, and spends the next few weeks watching in terrified wonder as Nathan oscillates between jovial Romanticism and angry, violent paranoia and rage, which Sophie accepts with a peculiar calmness.

It doesn't look like I've described a first act, to say nothing of a two-and-a-half hour movie, but that's pretty much the whole narrative thrust of Sophie's Choice. It sounds like the set-up to a joke: "A Jew, a Polack, and a Southern boy get drunk together..." On the contrary, this is Serious Filmmaking about Serious Things, revealed only gradually. One day, Sophie is comfortable enough with Stingo that she tells him the story of her time in Auschwitz: her children were taken from her the moment they arrived and her little girl sent to the gas chambers; she herself became a secretary for the camp commandant, and was approached by the Resistance to smuggle a radio from his house, a task she will only undertake if they promise to find out if her son yet lives. The story she weaves is full of outrageous sorrows and indignities, and it affects Stingo greatly, but he later learns that bits and pieces of Sophie's histories aren't entirely true, and the great arc of his coming-of-age is not that he learns that men can be tyrants in one moment and passionate lovers the next, but that some moments in history are so unspeakably evil that they could drive a woman to deliberately re-write her own life's story to keep the darkness at bay.

The film's biggest conceptual problem is that it doesn't know what to be about: it's quite hard to argue that the primary dramatic arc isn't about Stingo's growth, but for the most part his function is to be our surrogate for observing the behavior of Sophie and Nathan. And they are, without a doubt, much more interesting than he is, which leads us to the second biggest problem, though I don't know if it's rightly "conceptual", or just part of the film's litany of failures: Stingo is a horribly banal protagonist, performed by MacNicol in a wilting, disaffected manner, and he makes it impossible to engage with the main narrative of Sophie's Choice at all, above and beyond the fact that the narrative seems to consist of an endless string of scenes where Nathan is alternately nice or insane. It's not just repetitive, its repetition has no point at all, and so we are stuck with a movie that is solidly 105 minutes of chamber featuring characters who we don't get to know except as the sum of their most outwardly obvious traits, and who aren't interesting even when we know them the best.

The lengthy flashback passage to Sophie's time at Auschwitz is infinitely more fascinating, and therein lies the exact problem: the film drags in the Holocaust as a pretext, justification, and prop for its maddeningly uninvolving framework narrative, in a manner that I can only call distasteful in the extreme. Filmmakers had been invoking the Holocaust as a cheap trick to get some unearned gravitas before Sophie's Choice, and they continue to do it - 2008's grossly exploitative The Boy in the Striped Pajamas makes Pakula's film look like an unabashed masterpiece - but that does not excuse Pakula for using this very serious subject in such a whorish manner. I will credit Sophie's Choice with this much: it's treatment of the Holocaust is not without merit, though it is kept strictly PG-rated (in an R-rated film), and this naturally makes the horrors of the Shoah seem much more pedestrian. At the same time, it offers a perspective that is not terribly common in movies (a non-Jew, inside the home of a commandant), and other than the crass way that it's incorporated into the rest of the film, it's treated without sensationalism or tawdriness. Which is a bit like saying "except for the temperature, Antarctica is a great place to live", but still.

The shallowest complaint, but maybe the most dearly felt, is that the movie drags and drags and drags, much more than it has to. The ten-minute flashback to Nathan and Sophie meeting? Could have been cut. The endless run of scenes of Nathan being angry and happy? Certainly could have been reduced. Making matters worse, though it's not the film's fault, is that the one fact that everybody knows about the movie is a huge spoiler, much like how the one thing everybody knows is that Rosebud is Charles Foster Kane's sled; or that George Taylor finds the Statue of Liberty buried on the beach. But Citizen Kane and Planet of the Apes have a lot going on that makes them worthwhile movies besides their twist endings; Sophie's Choice is much less accomplished than either of them, and much longer, so it turns into a deathly waiting game, wondering when the hell she picks which kid to kill.

How dearly I wish that I could obviate Pakula from this movie, having spent so much energy trying to defend him as a great director on the basis of his '70s movies - but that would not be possible. This is undeniably and obviously an Alan J. Pakula film, starting with the fact that it was the first time he ever received a writing credit, and solo at that (it's based on a novel by William Styron that might be quite exquisite, I don't know, but I strongly doubt it). Even beyond that, it is a prime example of the director's favorite theme and storytelling mode: a close look at people in a period of stressful and transition, with special emphasis on what happens to sexual behavior in that situation. Frankly, I think that if Pakula had come up with all of this on his own, the fishbowl-perspective threesome of Stingo, Sophie and Nathan would be the whole of the movie, depriving us of the thin merits of the Auschwitz segment.

Worse still, for the first time in his career Pakula really dropped the ball with Sophie's Choice behind the camera. The screenplay was maybe salvageable; many a director has done just that. Unfortunately, Pakula seemed intent on taking a sow's ear and showing off with pride exactly how much of a sow's ear it was. This is a man who worked with geniuses on the scale of Gordon Willis and Sven Nykvist, and made with them some of the most subtly brilliant visuals of the 1970s - sometimes not so subtly. Now he was working with Néstor Almendros, a fair genius in his own right, and the most interesting thing the two men could come up with was to find as many different angles as possible from which to shoot close-ups. It is as best a bland, functional-looking movie, though I suppose if pressed I'd admit that the daytime interiors were lit better than they had to be. Only the Auschwitz scenes are visually distinguished (my God! take out the Holocaust and the whole thing really does just suck like a tornado!), with a tremendously washed-out palette, and what looks to me like deliberately damaged stock meant to indicate age, although that might just be the awful DVD that remains the only digital release of the film. The compositions, mind you, are still uniformly bland, but at least they are bland in desaturated grime.

I must also point out, just briefly, that Marvin Hamlisch's score is an affront to good taste; portentous and dramatic without sacrificing any schmaltz.

Many of these points are conceded by those who have kept the film's memory alive these many decades; especially Stingo's lack of value as a lead character. "But", comes the invariable rejoinder, "it is such a magnificent vehicle for Meryl Streep!" Indeed, you don't have to look very far at all to find people ready to call her Oscar-winning performance as Sophie the single best bit of film acting in history. Setting aside that specifically as the naïveté of people who haven't seen enough movies, I couldn't in good faith call it the best performance of Streep's career; I don't even know if I'd say it's the best performance nominated for that year's Oscar. I'm not a fool, and I certainly admit that Streep's work is formally immaculate: the nuances of her Polish-American accent, her juggling of three, count 'em, three languages, and the very precise way she physically embodies Sophie's self-immolating, hidden grief. But the performance is so perfect in the details that Streep, a great actress that I love, seems to have unaccountably forgotten to feel anything. Her precision is a chilly precision; only in the "choice" scene, where she screams that they should take her daughter, do I feel anything but the respect for what amounts to the most perfect acting class exercise in history. Frankly, I much prefer Kline's performance to Streep's: in his film debut, after much success on the New York stage, he explodes with vitality, and even when the film gives him silly things to do, he makes the most of them.

Worse than just the misery of watching a long, boring, offensive movie, is watching a movie that is all of those things and represents the hideous fall from grace of a fine director. Thankfully, Pakula never returned to the dull Oscarbaiting of this particular waste of time, though the slipping that had been part of his career ever since the late '70s was irreversible now. Especially since he didn't regard Sophie's Choice as a failure, there was no returning to the masterpiece phase of his career. Thus beginneth the reputation of Alan J. Pakula, hack director, a reputation that he is still stuck with, despite being for several years about as far from a "hack" as anyone could be.

If you had only heard of the film, but not seen it, and I asked you to summarise what you know about it, I think you would almost certainly give an answer along the lines of "Meryl Streep has to choose one of her children to give up to the Nazis". So close, but no, that's not it. Technically, yes, I suppose you could describe it that way, much as you could describe Casablanca as "a night club owner shoots a Nazi major." Yes, it does happen in the film - that's exactly the choice mentioned in the title. But it's not at all what Sophie's Choice is "about". It's rather about a callow young Southerner named Stingo (Peter MacNicol) who travels to Brooklyn in the summer of 1947 to find himself as a writer, and falls in with a most peculiar couple that lives above him in a boarding house: Sophie Zawistowski (Streep), a Polish Catholic who survived the camp at Auschwitz-Birkenau, and Nathan Landau (Kevin Kline), a New York Jew who rescued her from anemia when she was still wasting from the traumas she suffered under the Germans. The first time Stingo sees either of these characters, it's when they're in the middle of a vicious fight on the stairs right outside his room; less than twenty-hour hours later they've made up and invited the boy to join in their free-spirited life as their new best friend. Innocent and anxious to discover the colorful New York freedom of spirit that he came north to find, Stingo happily jumps into their lives, and spends the next few weeks watching in terrified wonder as Nathan oscillates between jovial Romanticism and angry, violent paranoia and rage, which Sophie accepts with a peculiar calmness.

It doesn't look like I've described a first act, to say nothing of a two-and-a-half hour movie, but that's pretty much the whole narrative thrust of Sophie's Choice. It sounds like the set-up to a joke: "A Jew, a Polack, and a Southern boy get drunk together..." On the contrary, this is Serious Filmmaking about Serious Things, revealed only gradually. One day, Sophie is comfortable enough with Stingo that she tells him the story of her time in Auschwitz: her children were taken from her the moment they arrived and her little girl sent to the gas chambers; she herself became a secretary for the camp commandant, and was approached by the Resistance to smuggle a radio from his house, a task she will only undertake if they promise to find out if her son yet lives. The story she weaves is full of outrageous sorrows and indignities, and it affects Stingo greatly, but he later learns that bits and pieces of Sophie's histories aren't entirely true, and the great arc of his coming-of-age is not that he learns that men can be tyrants in one moment and passionate lovers the next, but that some moments in history are so unspeakably evil that they could drive a woman to deliberately re-write her own life's story to keep the darkness at bay.

The film's biggest conceptual problem is that it doesn't know what to be about: it's quite hard to argue that the primary dramatic arc isn't about Stingo's growth, but for the most part his function is to be our surrogate for observing the behavior of Sophie and Nathan. And they are, without a doubt, much more interesting than he is, which leads us to the second biggest problem, though I don't know if it's rightly "conceptual", or just part of the film's litany of failures: Stingo is a horribly banal protagonist, performed by MacNicol in a wilting, disaffected manner, and he makes it impossible to engage with the main narrative of Sophie's Choice at all, above and beyond the fact that the narrative seems to consist of an endless string of scenes where Nathan is alternately nice or insane. It's not just repetitive, its repetition has no point at all, and so we are stuck with a movie that is solidly 105 minutes of chamber featuring characters who we don't get to know except as the sum of their most outwardly obvious traits, and who aren't interesting even when we know them the best.

The lengthy flashback passage to Sophie's time at Auschwitz is infinitely more fascinating, and therein lies the exact problem: the film drags in the Holocaust as a pretext, justification, and prop for its maddeningly uninvolving framework narrative, in a manner that I can only call distasteful in the extreme. Filmmakers had been invoking the Holocaust as a cheap trick to get some unearned gravitas before Sophie's Choice, and they continue to do it - 2008's grossly exploitative The Boy in the Striped Pajamas makes Pakula's film look like an unabashed masterpiece - but that does not excuse Pakula for using this very serious subject in such a whorish manner. I will credit Sophie's Choice with this much: it's treatment of the Holocaust is not without merit, though it is kept strictly PG-rated (in an R-rated film), and this naturally makes the horrors of the Shoah seem much more pedestrian. At the same time, it offers a perspective that is not terribly common in movies (a non-Jew, inside the home of a commandant), and other than the crass way that it's incorporated into the rest of the film, it's treated without sensationalism or tawdriness. Which is a bit like saying "except for the temperature, Antarctica is a great place to live", but still.

The shallowest complaint, but maybe the most dearly felt, is that the movie drags and drags and drags, much more than it has to. The ten-minute flashback to Nathan and Sophie meeting? Could have been cut. The endless run of scenes of Nathan being angry and happy? Certainly could have been reduced. Making matters worse, though it's not the film's fault, is that the one fact that everybody knows about the movie is a huge spoiler, much like how the one thing everybody knows is that Rosebud is Charles Foster Kane's sled; or that George Taylor finds the Statue of Liberty buried on the beach. But Citizen Kane and Planet of the Apes have a lot going on that makes them worthwhile movies besides their twist endings; Sophie's Choice is much less accomplished than either of them, and much longer, so it turns into a deathly waiting game, wondering when the hell she picks which kid to kill.

How dearly I wish that I could obviate Pakula from this movie, having spent so much energy trying to defend him as a great director on the basis of his '70s movies - but that would not be possible. This is undeniably and obviously an Alan J. Pakula film, starting with the fact that it was the first time he ever received a writing credit, and solo at that (it's based on a novel by William Styron that might be quite exquisite, I don't know, but I strongly doubt it). Even beyond that, it is a prime example of the director's favorite theme and storytelling mode: a close look at people in a period of stressful and transition, with special emphasis on what happens to sexual behavior in that situation. Frankly, I think that if Pakula had come up with all of this on his own, the fishbowl-perspective threesome of Stingo, Sophie and Nathan would be the whole of the movie, depriving us of the thin merits of the Auschwitz segment.

Worse still, for the first time in his career Pakula really dropped the ball with Sophie's Choice behind the camera. The screenplay was maybe salvageable; many a director has done just that. Unfortunately, Pakula seemed intent on taking a sow's ear and showing off with pride exactly how much of a sow's ear it was. This is a man who worked with geniuses on the scale of Gordon Willis and Sven Nykvist, and made with them some of the most subtly brilliant visuals of the 1970s - sometimes not so subtly. Now he was working with Néstor Almendros, a fair genius in his own right, and the most interesting thing the two men could come up with was to find as many different angles as possible from which to shoot close-ups. It is as best a bland, functional-looking movie, though I suppose if pressed I'd admit that the daytime interiors were lit better than they had to be. Only the Auschwitz scenes are visually distinguished (my God! take out the Holocaust and the whole thing really does just suck like a tornado!), with a tremendously washed-out palette, and what looks to me like deliberately damaged stock meant to indicate age, although that might just be the awful DVD that remains the only digital release of the film. The compositions, mind you, are still uniformly bland, but at least they are bland in desaturated grime.

I must also point out, just briefly, that Marvin Hamlisch's score is an affront to good taste; portentous and dramatic without sacrificing any schmaltz.

Many of these points are conceded by those who have kept the film's memory alive these many decades; especially Stingo's lack of value as a lead character. "But", comes the invariable rejoinder, "it is such a magnificent vehicle for Meryl Streep!" Indeed, you don't have to look very far at all to find people ready to call her Oscar-winning performance as Sophie the single best bit of film acting in history. Setting aside that specifically as the naïveté of people who haven't seen enough movies, I couldn't in good faith call it the best performance of Streep's career; I don't even know if I'd say it's the best performance nominated for that year's Oscar. I'm not a fool, and I certainly admit that Streep's work is formally immaculate: the nuances of her Polish-American accent, her juggling of three, count 'em, three languages, and the very precise way she physically embodies Sophie's self-immolating, hidden grief. But the performance is so perfect in the details that Streep, a great actress that I love, seems to have unaccountably forgotten to feel anything. Her precision is a chilly precision; only in the "choice" scene, where she screams that they should take her daughter, do I feel anything but the respect for what amounts to the most perfect acting class exercise in history. Frankly, I much prefer Kline's performance to Streep's: in his film debut, after much success on the New York stage, he explodes with vitality, and even when the film gives him silly things to do, he makes the most of them.

Worse than just the misery of watching a long, boring, offensive movie, is watching a movie that is all of those things and represents the hideous fall from grace of a fine director. Thankfully, Pakula never returned to the dull Oscarbaiting of this particular waste of time, though the slipping that had been part of his career ever since the late '70s was irreversible now. Especially since he didn't regard Sophie's Choice as a failure, there was no returning to the masterpiece phase of his career. Thus beginneth the reputation of Alan J. Pakula, hack director, a reputation that he is still stuck with, despite being for several years about as far from a "hack" as anyone could be.