Disney Animation: Forget about your worries and your strife

There is a famous story told about how Walt Disney, having picked the story for his studio's 19th animated feature in his customary jolly autocratic style, handed copies of Rudyard Kipling's The Jungle Book and its sequel to four of his story men - Larry Clemmons, Ralph Wright, Ken Anderson, and Vance Gerry - and gave them only one piece of instruction: "The first thing I want you to is not to read it".

Instead, Walt described for the writers his ideas for the characters, based upon Kipling's original figures but made, across the board, much more comic and lighter. Lightness, it would become clear, was a major concern for the producer. Which would, you might think, make Kipling's novel an odd choice of subject matter: though it was written for children, it is (like much Victorian children's fiction) full of danger and darkness, trusting the that it's young target audience will be able to survive the experience of reading, and therefore surviving in the popular imagination for more than a century, while so many "nice" children's stories have faded instantly from memory. At any rate, I was starting to say that I suspect that Disney selected this project because he knew that its large cast of a wide array of animals - pythons and tigers and bears, elephants, wolves, and oh yeah, one little human boy - was ideally suited to the medium of animation, and smarting from the lukewarm response to The Sword in the Stone, and still probably resisting the sketchy, graphic animation style that had been introduced by One Hundred and One Dalmatians, he wanted to make a fun, epic-sized cartoon that would show off what his team of animators could do, while still being a delightful, bouncy entertainment for kids of all ages.

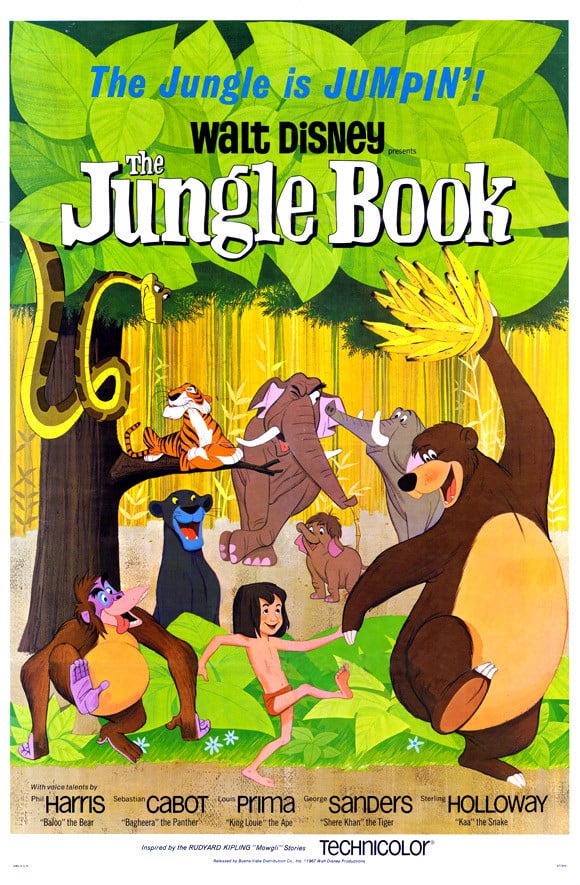

Walt's personal involvement with the development of The Jungle Book was greater than it had been for any other film of the Silver Age: he suggest gags, vetoed plot-lines and characters that weren't going anywhere, and generally fussed over the story like he hadn't since World War II came along and took the fun out of animation. When the initial story drafts hewed to closely to Kipling's darker vision, he threw them out and started from scratch; when the original songwriter, Terry Gilkyson, presented a soundtrack that was far moodier and inflected with Indian flavor, Disney took him off the project, saving only "The Bare Necessities", which would become the film's signature tune, and putting the Sherman Brothers on the case. The important thing was to keep it fun and bubbly: his vision for the project can be quickly spotted when we observe that for the first time since The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad, all the way back in 1949, there was a celebrity voice cast hired. And not just any celebrity cast: Phil Harris (playing Baloo the bear) and Louis Prima (playing King Louie the orangutan) were both noteworthy figures in jazz music, at least the kind of edges-sanded-off jazz that Walt Disney would have been comfortable enough. And their personae did a great deal to drive the film: not only with the characters they played largely derived from the actors' personalities and mannerisms, but the whole tone of The Jungle Book can be called "jazzy"; it is by far the most contemporary in expression and attitude of any Disney animated feature to that time, re-casting the Indian jungle of the late 19th Century as some kind of 1960s music club, not only featuring a beatnik sloth bear who is perfectly sanguine to use phrases like, "I'm gone, man. Solid gone", but a quartet of vultures who would very much like to be The Beatles (and, allegedly, almost were; but the band vetoed this idea, preferring to do something dignified like Magical Mystery Tour instead).

The "pop culture and celebrity" angle that would later be exploited and driven into the ground by DreamWorks Animation in the 2000s was not a mode that Disney had explored yet, and this more than anything speaks to the new direction Walt wanted this project to take. This was going to be fun movie, dammit, something delightful and silly, driven by appealing characters who felt modern and relatable, not like fusty old fairy tale creations out of a storybook. But at the same time, it was going to have heart, and real heartwarming drama, that's what. It was in short meant to be everything that a Disney Studios feature could be, but hadn't been for too long.

Walt Disney died on December 15, 1966, while The Jungle Book was still in production (I have read that most of the animation had been completed, but very little had been painted; this could well be a romantic ahistoricism to make it seem that Walt saw a complete workprint of the film). A lifetime of smoking had caught up to him, and his left lung had been removed the month prior, riddled with tumours; he came out of the surgery and underwent chemo, but the damage had been done, and he spent the last two weeks of his life - including his 65th birthday on December 5th - in the hospital.

The last animation he saw released was the short "Winnie the Pooh and the Honey Tree" in February of that year, and its success pleased him; he certainly had high hopes that The Jungle Book would continue the legacy of Disney Animation, even in the new cheaper form that it had been obliged to take during the 1960s. This would indeed turn out to be the case, for when the finished project was released on October 18, 1967, it was greeted by some of the most uniformly positive reviews of any Silver Age feature, while becoming the highest-grossing film of the year. One must assume that a large part of this was due to nostalgia and mourning; how could it not be? Walt's death was one of those national traumas that comes along only rarely, though more often in the 1960s than in most decades.

This is not the place to talk about the particulars of Walt's life, but I hope you'll indulge me: for I must confess that for all his notorious character flaws, be they antisemitism, a racism that was not probably more pronounced than anyone else felt in his generation, but given a bullhorn because of his cultural prominence, a nasty habit of fighting unions, and all the rest, I do completely buy into the company-promulgated myth that he was a uniquely imaginative genius of popular entertainment; his desire to create new worlds to play in and to share with others has been only rarely matched and never surpassed. I have the sense that if Walt could have died penniless, knowing that he'd spent every dime on making something truly wonderful, he would have been thrilled to do so, and the financial empire he created when Disneyland opened was merely a nice bonus. For it is known that he took to heart the failures of his most ambitious projects like Fantasia, and I think that he was probably not upset that Fantasia did not make money, so much as he was upset that he therefore did not get to keep making more Fantasias. His was a creative soul, doubtlessly given far too much to sentimentality and easy traditionalism, but I can never for a moment believe that he was insincere. If the man who appeared on television to ramble on about his EPCOT project in Florida was faking his genuine, boyish enthusiasm, then he missed his calling: for in that case Walt Disney could surely have been the finest actor of the 20th Century.

This, then, is the man who was finally re-energised to pitch in with the animation studio to make The Jungle Book the best it could possibly be. Which makes it not merely disappointing but frankly soul-wracking that The Jungle Book isn't any better than it is - for my tastes, the worst film of Disney's Silver Age, and not by a terribly close margin, either. It has the feeling of a transitional film, with almost as much in common with the sometimes dreadful movies to come out in the two decades following it as with the films in the decade-and-a-half preceding it. The animation quality in particular is a shocking sight: if someone told me that it was the halfway point between the invention of xerography-based animation in One Hundred and One Dalmatians and the smoothness and refinement of that technology in The Sword in the Stone, I'd believe them without a thought; but to know that The Jungle Book actually followed The Sword in the Stone by four years seems an impossibility: it is such a dramatic roll-back in quality as to beggar belief.

As for the narrative content of the film, well, there is the obvious matter of the sickly-cute ending that it even annoyed the animators responsible for executing it (the directing animator for this sequence was Ollie Johnston: and when he of all people thought that something was too sentimental, you can be damn sure that it was too sentimental). But that's just the capstone to a movie that was ambling about without much of a point for quite some time before it finally ends. It suffers in particular from delaying the introduction of its villain, and thus the active stage of its conflict, until about two-thirds of the way through the movie; everything before that is simple, and mostly unengaging, comic banter.

In essence, the problem is this: the movie banks everything on the characters being so delightful that you just enjoy spending time with them, watching as they have low-key little adventures, and this would work brilliantly - if the characters were up to it. I certainly know that The Jungle Book has a fairly cast-iron reputation, so I suppose I must be in the minority in this respect, but I don't really have that much affection for several of the major characters: Baloo in particular annoys me with his boisterous idiocy (and for that matter, I have little use for Phil Harris's two other Disney characters, but we'll get to them soon enough), even if "The Bare Necessities" is a pretty fun song. By the same token, although I like King Louie - Prima's performance is wonderfully energetic, and it is possible that no person was ever so outspoken about his delight in having voiced a Disney character - and his number "I Wanna Be Like You" is one of the Sherman's best compositions, his monkey retainers are so insanely irritating that I very nearly want to fast-forward every time I re-watch the film (which, oddly, is more often than for several Disney projects I like a great deal better).

As for little Mowgli (here pronounced MOE-glee, rather than Kipling's preferred "MAU-glee"), the human "man-cub" whose return to a man village forms the narrative spine of what is otherwise a mostly episodic movie, he's essentially just a blank slate. Voiced by director Wolfgang Reitherman's son Bruce without much distinction, his only function in the film is to be in peril that he doesn't really understand, and to outglare animals who should, in theory, be able to destroy him in an eye blink. But he's fundamentally impossible to understand or sympathise with; while everyone around him insists that he is a human and must be around humans, I rather agree with Mowgli himself that he's no human at all: he was raised around animals, in an animal way of living, and frankly nothing he does up until that ridiculous cutesy-poo finale has anything to do with any human feeling I can recall having. I mean, I was a ten-year-old boy myself, once - I suspect that I saw The Jungle Book at least once in that period, for its VHS release occurred when I was nine - but I can't recall ever having a glimmer of affection for Mowgli at all. He simple doesn't have a personality worth mentioning.

Happily, to my mind the characters that work are better than the characters that fail are bad. King Louie, with his broad physicality and loopy personality, I have mentioned (an aside: I once read a well-intentioned complaint that Disney would have the temerity to cast a black actor as an ape, something that I imagine would have amused the Italian-American Prima if he'd ever heard it). I also have great affection for the panther Bagheera, largely a function of the great vocal work done by Sebastian Cabot, a recently-minted member of the Disney Stock Company (he'd voiced Sir Ector in The Sword in the Stone, and narrated the Winnie the Pooh short), very serious and ceremonial but a great humanist (is that the word?) nonetheless. And I am always amused by the caricatured English elephant regiment, boasting two great performers: Disney regulars J. Pat O'Malley and Verna Felton, in her last of many great turns for the studio (she died just one day prior to Walt Disney), stretching back to playing the imperious matriarch elephant in Dumbo, 26 years earlier. It has always given me a peculiar degree of joy that she bookended her Disney career with two pachyderms.

Unquestionably, the two stand-out characters are the film's villains: Kaa the python (voiced by the irreplaceable Sterling Holloway), and Shere Khan the tiger (speaking in the bored, silken tones of the magnificent George Sanders, in the only voice-acting work of his career). It was not the first time, and it would hardly be the last, that a Disney film should be overwhelmed by its antagonists; but they are particularly well-rendered in this film, nor could they be more different: the snake is a mewling, pitiful idiot who has to rely on his cunning to do anything, while the tiger is so aware of his reputation and presence that he knows that he doesn't actually have to act threatening, thus the hint of bored amusement throughout. The one scene these two characters share is the non-musical highlight of the film, with two very different concepts of wickedness dueling for prominence and ending in a draw.

That particular scene was also supervised entirely by Milt Kahl, the directing animator for both characters, and much as Frank Thomas and Marc Davis did their best work in villains, so did Kahl (usually cited as the animators' animator among Disney's Nine Old Men) never surpass either Kaa or Shere Khan - the tiger especially, who is a case study in how to create a character through the most delicate movements. Watch his shoulders as he walks! it is not only a miracle of observation but of mood-setting as well: you know from his every step that Shere Khan is just a moment's thought away from pouncing. And the smug, bastardly grin he perpetually wears matches Sanders's performance to a T. He really is one of the most amazingly dangerous villains in Disney, with none of the comic padding that keeps so many of them from true wickedness.

"But Tim", you may ask, "didn't you say the animation was bad? Well, is it or isn't it?" Ah, yes. It's both, which isn't as cheap an answer as it sounds. The actual physical act of character animation is quite extraordinarily good in The Jungle Book, the best of the '60s: Shere Khan alone makes that argument, as would the dance between Louie and Baloo (Thomas and Kahl working together, a reunion of the great team behind the wizards' duel in The Sword in the Stone). And I would also not hesitate to praise the very Ollie Johnston-esque degree to which characters in this film are in constant physical contact; I have seen it alleged without reference that Johnston did more work on this film than anyone else, which I would believe if only because it was his innovation to stress how character touching can have an emotional impact, and he was always the best at it - and say what one will about the value of Mowgli and Baloo, their physical affection is one of the best parts of the film, emotionally speaking. Wolfgang Reitherman, in his second solo directing project, absolutely did a wonderful job marshaling the talents of all the animators, better than he ever did before or after.

No, what I dislike about the animation - strongly - is the actual look of it. This was the third "sketchy" Disney film, and the two earlier ones had managed to work around it: One Hundred and One Dalmatians by marrying the graphic character design with equally graphic backgrounds that looked just as stylised, and The Sword in the Stone by advancing the graphic technique enough that it didn't really seem so rough. But The Jungle Book seemingly goes out of its way to emphasise the rough, pencilled quality of the animation, even more maybe than One Hundred and One Dalmatians did: there are certain details, such as Mowgli's loincloth or Baloo's whole body, that don't even look like they were transferred to cels first, but just painted right there on the paper where the animators drew them.

Arguably, this half-finished look is well-combined with the jazzy, loose style of the narrative; but it clashes terribly with the lovely oil backgrounds, more detailed by far than in the last two films, and never before in any Disney film did the essential contrast between painted scenes and cel-animated characters seem so jarring. The characters, both in design and execution are so obviously cartoons; the backgrounds are of the same realistic quality of Cinderella, and it bothers me.

Even worse is the slipshod cheapness that the sketchy animation implies. In the previous xerographic films, it seemed like it might be legitimately an aesthetic choice, but here it can only be regarded as cost-cutting. This impression is underscored by the amount of recycled animation present, far more than in any previous film: the scene of Mowgli and his wolf brothers is taken from The Sword in the Stone (and Mowgli's design overall seem rather similar to the Wart), a chase scene in the ruins between Louie, Baloo and Bagheera was lifted from The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad, and Shere Khan's introduction comes when he is seen stalking a deer that you would never find in the jungles of India - because it's Bambi's mother.

Far more damningly, the recycling is even of animation from within The Jungle Book itself: Kaa falls from a tree in the exact same way twice, and is indeed lit the same way: never mind that it's night in one scene and midday in the other. And both times we see the elephants, they walk in exactly - exactly - the same way. Ironically, in the one place where a little bit of recycling could have been useful, it's ignored: and thus Shere Khan's stripes change, sometimes dramatically, from shot to shot.

I do not know if this was laziness, sloppiness, a desire for speed, or just the need to keep things cheap, but it set up a pattern of sub-par animation quality - as compared to technical skill of the animation - that would prove a severe Achilles' heel for the studio in the years to come. The combination of Walt's death and the box-office success of three consecutive cheap kids' movies led to a devaluation of basic craftsmanship, and that in turn to the first sustained run of truly mediocre films in the studio's history. But that is a story for another time.

Instead, Walt described for the writers his ideas for the characters, based upon Kipling's original figures but made, across the board, much more comic and lighter. Lightness, it would become clear, was a major concern for the producer. Which would, you might think, make Kipling's novel an odd choice of subject matter: though it was written for children, it is (like much Victorian children's fiction) full of danger and darkness, trusting the that it's young target audience will be able to survive the experience of reading, and therefore surviving in the popular imagination for more than a century, while so many "nice" children's stories have faded instantly from memory. At any rate, I was starting to say that I suspect that Disney selected this project because he knew that its large cast of a wide array of animals - pythons and tigers and bears, elephants, wolves, and oh yeah, one little human boy - was ideally suited to the medium of animation, and smarting from the lukewarm response to The Sword in the Stone, and still probably resisting the sketchy, graphic animation style that had been introduced by One Hundred and One Dalmatians, he wanted to make a fun, epic-sized cartoon that would show off what his team of animators could do, while still being a delightful, bouncy entertainment for kids of all ages.

Walt's personal involvement with the development of The Jungle Book was greater than it had been for any other film of the Silver Age: he suggest gags, vetoed plot-lines and characters that weren't going anywhere, and generally fussed over the story like he hadn't since World War II came along and took the fun out of animation. When the initial story drafts hewed to closely to Kipling's darker vision, he threw them out and started from scratch; when the original songwriter, Terry Gilkyson, presented a soundtrack that was far moodier and inflected with Indian flavor, Disney took him off the project, saving only "The Bare Necessities", which would become the film's signature tune, and putting the Sherman Brothers on the case. The important thing was to keep it fun and bubbly: his vision for the project can be quickly spotted when we observe that for the first time since The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad, all the way back in 1949, there was a celebrity voice cast hired. And not just any celebrity cast: Phil Harris (playing Baloo the bear) and Louis Prima (playing King Louie the orangutan) were both noteworthy figures in jazz music, at least the kind of edges-sanded-off jazz that Walt Disney would have been comfortable enough. And their personae did a great deal to drive the film: not only with the characters they played largely derived from the actors' personalities and mannerisms, but the whole tone of The Jungle Book can be called "jazzy"; it is by far the most contemporary in expression and attitude of any Disney animated feature to that time, re-casting the Indian jungle of the late 19th Century as some kind of 1960s music club, not only featuring a beatnik sloth bear who is perfectly sanguine to use phrases like, "I'm gone, man. Solid gone", but a quartet of vultures who would very much like to be The Beatles (and, allegedly, almost were; but the band vetoed this idea, preferring to do something dignified like Magical Mystery Tour instead).

The "pop culture and celebrity" angle that would later be exploited and driven into the ground by DreamWorks Animation in the 2000s was not a mode that Disney had explored yet, and this more than anything speaks to the new direction Walt wanted this project to take. This was going to be fun movie, dammit, something delightful and silly, driven by appealing characters who felt modern and relatable, not like fusty old fairy tale creations out of a storybook. But at the same time, it was going to have heart, and real heartwarming drama, that's what. It was in short meant to be everything that a Disney Studios feature could be, but hadn't been for too long.

Walt Disney died on December 15, 1966, while The Jungle Book was still in production (I have read that most of the animation had been completed, but very little had been painted; this could well be a romantic ahistoricism to make it seem that Walt saw a complete workprint of the film). A lifetime of smoking had caught up to him, and his left lung had been removed the month prior, riddled with tumours; he came out of the surgery and underwent chemo, but the damage had been done, and he spent the last two weeks of his life - including his 65th birthday on December 5th - in the hospital.

The last animation he saw released was the short "Winnie the Pooh and the Honey Tree" in February of that year, and its success pleased him; he certainly had high hopes that The Jungle Book would continue the legacy of Disney Animation, even in the new cheaper form that it had been obliged to take during the 1960s. This would indeed turn out to be the case, for when the finished project was released on October 18, 1967, it was greeted by some of the most uniformly positive reviews of any Silver Age feature, while becoming the highest-grossing film of the year. One must assume that a large part of this was due to nostalgia and mourning; how could it not be? Walt's death was one of those national traumas that comes along only rarely, though more often in the 1960s than in most decades.

This is not the place to talk about the particulars of Walt's life, but I hope you'll indulge me: for I must confess that for all his notorious character flaws, be they antisemitism, a racism that was not probably more pronounced than anyone else felt in his generation, but given a bullhorn because of his cultural prominence, a nasty habit of fighting unions, and all the rest, I do completely buy into the company-promulgated myth that he was a uniquely imaginative genius of popular entertainment; his desire to create new worlds to play in and to share with others has been only rarely matched and never surpassed. I have the sense that if Walt could have died penniless, knowing that he'd spent every dime on making something truly wonderful, he would have been thrilled to do so, and the financial empire he created when Disneyland opened was merely a nice bonus. For it is known that he took to heart the failures of his most ambitious projects like Fantasia, and I think that he was probably not upset that Fantasia did not make money, so much as he was upset that he therefore did not get to keep making more Fantasias. His was a creative soul, doubtlessly given far too much to sentimentality and easy traditionalism, but I can never for a moment believe that he was insincere. If the man who appeared on television to ramble on about his EPCOT project in Florida was faking his genuine, boyish enthusiasm, then he missed his calling: for in that case Walt Disney could surely have been the finest actor of the 20th Century.

This, then, is the man who was finally re-energised to pitch in with the animation studio to make The Jungle Book the best it could possibly be. Which makes it not merely disappointing but frankly soul-wracking that The Jungle Book isn't any better than it is - for my tastes, the worst film of Disney's Silver Age, and not by a terribly close margin, either. It has the feeling of a transitional film, with almost as much in common with the sometimes dreadful movies to come out in the two decades following it as with the films in the decade-and-a-half preceding it. The animation quality in particular is a shocking sight: if someone told me that it was the halfway point between the invention of xerography-based animation in One Hundred and One Dalmatians and the smoothness and refinement of that technology in The Sword in the Stone, I'd believe them without a thought; but to know that The Jungle Book actually followed The Sword in the Stone by four years seems an impossibility: it is such a dramatic roll-back in quality as to beggar belief.

As for the narrative content of the film, well, there is the obvious matter of the sickly-cute ending that it even annoyed the animators responsible for executing it (the directing animator for this sequence was Ollie Johnston: and when he of all people thought that something was too sentimental, you can be damn sure that it was too sentimental). But that's just the capstone to a movie that was ambling about without much of a point for quite some time before it finally ends. It suffers in particular from delaying the introduction of its villain, and thus the active stage of its conflict, until about two-thirds of the way through the movie; everything before that is simple, and mostly unengaging, comic banter.

In essence, the problem is this: the movie banks everything on the characters being so delightful that you just enjoy spending time with them, watching as they have low-key little adventures, and this would work brilliantly - if the characters were up to it. I certainly know that The Jungle Book has a fairly cast-iron reputation, so I suppose I must be in the minority in this respect, but I don't really have that much affection for several of the major characters: Baloo in particular annoys me with his boisterous idiocy (and for that matter, I have little use for Phil Harris's two other Disney characters, but we'll get to them soon enough), even if "The Bare Necessities" is a pretty fun song. By the same token, although I like King Louie - Prima's performance is wonderfully energetic, and it is possible that no person was ever so outspoken about his delight in having voiced a Disney character - and his number "I Wanna Be Like You" is one of the Sherman's best compositions, his monkey retainers are so insanely irritating that I very nearly want to fast-forward every time I re-watch the film (which, oddly, is more often than for several Disney projects I like a great deal better).

As for little Mowgli (here pronounced MOE-glee, rather than Kipling's preferred "MAU-glee"), the human "man-cub" whose return to a man village forms the narrative spine of what is otherwise a mostly episodic movie, he's essentially just a blank slate. Voiced by director Wolfgang Reitherman's son Bruce without much distinction, his only function in the film is to be in peril that he doesn't really understand, and to outglare animals who should, in theory, be able to destroy him in an eye blink. But he's fundamentally impossible to understand or sympathise with; while everyone around him insists that he is a human and must be around humans, I rather agree with Mowgli himself that he's no human at all: he was raised around animals, in an animal way of living, and frankly nothing he does up until that ridiculous cutesy-poo finale has anything to do with any human feeling I can recall having. I mean, I was a ten-year-old boy myself, once - I suspect that I saw The Jungle Book at least once in that period, for its VHS release occurred when I was nine - but I can't recall ever having a glimmer of affection for Mowgli at all. He simple doesn't have a personality worth mentioning.

Happily, to my mind the characters that work are better than the characters that fail are bad. King Louie, with his broad physicality and loopy personality, I have mentioned (an aside: I once read a well-intentioned complaint that Disney would have the temerity to cast a black actor as an ape, something that I imagine would have amused the Italian-American Prima if he'd ever heard it). I also have great affection for the panther Bagheera, largely a function of the great vocal work done by Sebastian Cabot, a recently-minted member of the Disney Stock Company (he'd voiced Sir Ector in The Sword in the Stone, and narrated the Winnie the Pooh short), very serious and ceremonial but a great humanist (is that the word?) nonetheless. And I am always amused by the caricatured English elephant regiment, boasting two great performers: Disney regulars J. Pat O'Malley and Verna Felton, in her last of many great turns for the studio (she died just one day prior to Walt Disney), stretching back to playing the imperious matriarch elephant in Dumbo, 26 years earlier. It has always given me a peculiar degree of joy that she bookended her Disney career with two pachyderms.

Unquestionably, the two stand-out characters are the film's villains: Kaa the python (voiced by the irreplaceable Sterling Holloway), and Shere Khan the tiger (speaking in the bored, silken tones of the magnificent George Sanders, in the only voice-acting work of his career). It was not the first time, and it would hardly be the last, that a Disney film should be overwhelmed by its antagonists; but they are particularly well-rendered in this film, nor could they be more different: the snake is a mewling, pitiful idiot who has to rely on his cunning to do anything, while the tiger is so aware of his reputation and presence that he knows that he doesn't actually have to act threatening, thus the hint of bored amusement throughout. The one scene these two characters share is the non-musical highlight of the film, with two very different concepts of wickedness dueling for prominence and ending in a draw.

That particular scene was also supervised entirely by Milt Kahl, the directing animator for both characters, and much as Frank Thomas and Marc Davis did their best work in villains, so did Kahl (usually cited as the animators' animator among Disney's Nine Old Men) never surpass either Kaa or Shere Khan - the tiger especially, who is a case study in how to create a character through the most delicate movements. Watch his shoulders as he walks! it is not only a miracle of observation but of mood-setting as well: you know from his every step that Shere Khan is just a moment's thought away from pouncing. And the smug, bastardly grin he perpetually wears matches Sanders's performance to a T. He really is one of the most amazingly dangerous villains in Disney, with none of the comic padding that keeps so many of them from true wickedness.

"But Tim", you may ask, "didn't you say the animation was bad? Well, is it or isn't it?" Ah, yes. It's both, which isn't as cheap an answer as it sounds. The actual physical act of character animation is quite extraordinarily good in The Jungle Book, the best of the '60s: Shere Khan alone makes that argument, as would the dance between Louie and Baloo (Thomas and Kahl working together, a reunion of the great team behind the wizards' duel in The Sword in the Stone). And I would also not hesitate to praise the very Ollie Johnston-esque degree to which characters in this film are in constant physical contact; I have seen it alleged without reference that Johnston did more work on this film than anyone else, which I would believe if only because it was his innovation to stress how character touching can have an emotional impact, and he was always the best at it - and say what one will about the value of Mowgli and Baloo, their physical affection is one of the best parts of the film, emotionally speaking. Wolfgang Reitherman, in his second solo directing project, absolutely did a wonderful job marshaling the talents of all the animators, better than he ever did before or after.

No, what I dislike about the animation - strongly - is the actual look of it. This was the third "sketchy" Disney film, and the two earlier ones had managed to work around it: One Hundred and One Dalmatians by marrying the graphic character design with equally graphic backgrounds that looked just as stylised, and The Sword in the Stone by advancing the graphic technique enough that it didn't really seem so rough. But The Jungle Book seemingly goes out of its way to emphasise the rough, pencilled quality of the animation, even more maybe than One Hundred and One Dalmatians did: there are certain details, such as Mowgli's loincloth or Baloo's whole body, that don't even look like they were transferred to cels first, but just painted right there on the paper where the animators drew them.

Arguably, this half-finished look is well-combined with the jazzy, loose style of the narrative; but it clashes terribly with the lovely oil backgrounds, more detailed by far than in the last two films, and never before in any Disney film did the essential contrast between painted scenes and cel-animated characters seem so jarring. The characters, both in design and execution are so obviously cartoons; the backgrounds are of the same realistic quality of Cinderella, and it bothers me.

Even worse is the slipshod cheapness that the sketchy animation implies. In the previous xerographic films, it seemed like it might be legitimately an aesthetic choice, but here it can only be regarded as cost-cutting. This impression is underscored by the amount of recycled animation present, far more than in any previous film: the scene of Mowgli and his wolf brothers is taken from The Sword in the Stone (and Mowgli's design overall seem rather similar to the Wart), a chase scene in the ruins between Louie, Baloo and Bagheera was lifted from The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad, and Shere Khan's introduction comes when he is seen stalking a deer that you would never find in the jungles of India - because it's Bambi's mother.

Far more damningly, the recycling is even of animation from within The Jungle Book itself: Kaa falls from a tree in the exact same way twice, and is indeed lit the same way: never mind that it's night in one scene and midday in the other. And both times we see the elephants, they walk in exactly - exactly - the same way. Ironically, in the one place where a little bit of recycling could have been useful, it's ignored: and thus Shere Khan's stripes change, sometimes dramatically, from shot to shot.

I do not know if this was laziness, sloppiness, a desire for speed, or just the need to keep things cheap, but it set up a pattern of sub-par animation quality - as compared to technical skill of the animation - that would prove a severe Achilles' heel for the studio in the years to come. The combination of Walt's death and the box-office success of three consecutive cheap kids' movies led to a devaluation of basic craftsmanship, and that in turn to the first sustained run of truly mediocre films in the studio's history. But that is a story for another time.