A star is born

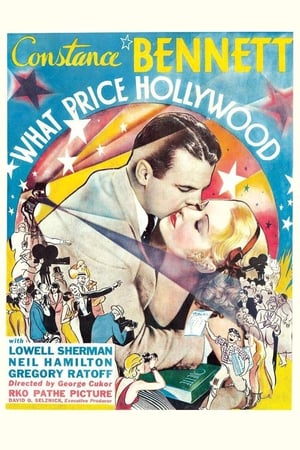

The very fine backstage melodrama What Price Hollywood? was released in 1932, and for all but the first five years of its life, it has been best known as being the unofficial-but-very-obvious basis for a different movie and its subsequent remakes. This is a goddamned shame, though it's not terribly difficult to see what happened. For one thing, as much as I hate to say anything against What Price Hollywood? (which has for me the privileged status of being a movie that I fell in love with without anybody else seeming to know it existed), the 1937 A Star Is Born probably is a better movie. For another, What Price Hollywood? was one of the many victims of the 1934 push to give the Production Code some actual teeth, which put a whole lot of movies out of circulation, and led them getting rather neutered remakes. It's a kind of weird thing, too, because whatever this film does against the Code, it does in a kind of meta way, by acknowledging the rampant scandals of '20s Hollywood, the highly contentious cycle of Tragic Unmarried Mothers Who Must Give Up Their Babies And Then Die pictures, and the fact that celebrities fuck around. But it doesn't actually engage with any of those things.

Anyway, the price of Hollywood, we'll eventually learn, is that you're expected to sacrifice a bit of your inner self, to become an ideal in the minds of the fans and the newspapers, even if that means you don't have the luxury of being a person. The victim who'll be thrust through this process is one Mary Evans (Constance Bennett), who gets the full "only in Hollywood" treatment: a waitress/aspiring actress at the Brown Derby, she and her coworkers have an elaborate ecosystem of waiting on the various famous people who come to that legendary establishment, and Mary is able to barter her way into serving Max Carey (Lowell Sherman), a famous producer and infamous drunkard. In hardly any time, she's gotten a tiny part in a movie that impresses studio head Julius Saxe (Gregory Ratoff) that she's under contract and getting a big push as the newest star in the Hollywood firmament.

And I do mean "in hardly any time" - there are big and little problems with What Price Hollywood? to go with its big and little strengths, but the biggest problem is surely that it is in a real motherfucking hurry. The film is a mere 88 minutes, and it flies through them like a rocket. I get it, there's a lot to cover, but it seems like Mary goes from shrieking out her lines in a hugely unconvincing squeal to having an ad campaign designed around her in about 16 hours. Which is, in fact, about how long it takes, if you track the film's internal chronology, and even for a fluffy fantasy, that's pushing it.

Besides, this isn't a fluffy fantasy, which is one of the film's great strengths. It is a rarity in all the legions of Hollywood films about the Hollywood film industry, in that it indulges in neither the pie-eyed fairy stories of instant stardom and happy-minded people doing their gosh-darndest to make really swell pictures for the rest of us to enjoy (the Singin' in the Rain approach), nor the equally self-regarding vision of Hollywood as a uniquely cruel moral cesspit that destroys every good thing it touches (the Sunset Blvd. approach). Rather, What Price Hollywood? considers that the commercial film industry is, first and foremost, a commercial industry, and the people working inside of it, at least in 1932, were salaried professionals, not mercurial artists. The backstage stuff that makes up most of the first half of the movie is, I would go so far as to say, shockingly unromantic and unfussy in working through the nuts and bolts of how movies get made, and how helpless drunks like Max can go exactly this far in their drunkenness, as long as the movies get made. Even the big "star is born" moment, in which Mary nails a scene of being flirty and then horrified to see a dead body, isn't depicted as a flash of great actorly insight, but the end result of a long night in which she practices how to run up and down a flight of stairs.

Really, the same thing applies to its inevitable turn into various melodramatic streaks, the most prominent of which involves Mary falling into a somewhat acrimonious form of love with polo star Lonny Borden (Neil Hamilton), who is too much of a prig to understand the bonds of friendship that form between these *sniff* movie people. Unlike the four incarnations of A Star Is Born, this isn't really a love story; Lonny and his generally obnoxious behavior is just one more thing that Mary has to cope with as she discovers both the highs and lows of life in the public eye, and the film is much more interested in examining how the celebrity media latches onto the lives of movie stars as an occupational hazard than it is in depicting a moral tragedy.

An interesting, unexpected set of emphases provided by the litany of writers (two of whom, Adela Rogers St. Johns and Jane Murfin, picked up an Oscar nomination for Best Original Story), and even more so by director George Cukor, making the sixth feature of his legendary, long-lived career, and the first one that remains more or less alive in the awareness of all but the most single-minded cinephiles. It's a weird fit given what we know of the later Cukor, whose best work is pretty much exclusively in character-driven comedy, whereas this has only a little humor and most of that is pretty dark-minded; yet it's fair to say that the strengths of his work here lead directly into the strengths of his exemplary career. Cukor was one of the great directors of actors - of women in particular, but he certainly does fine by Lowell Sherman in this case - foreground dialogues as the most visually interesting part of even the busiest frame. And there are some fine frames here, and a remarkably acute sense of place - 1932 was just about the earliest year of the sound era in which a camera could move so comfortably around the world, and while the film's exploration of Los Angeles is hardly a long trip, there are scenes that certainly benefit from an unexpected dash of realism, by '32 standards.

But what the film is really about is never the interior spaces swallowing up the characters, as was sometimes the case in Cukor's 1954 take on similar material, in A Star Is Born v2.0. It's always the characters themselves, however framed and packaged by their surroundings, and no matter how wide Cukor and his cinematographer, the great Charles Rosher, set their camera (and it can be awfully wide, particularly on the movie sets). The blocking always drives us towards the characters, and particularly Mary, the best performance in the great career of the deeply under-appreciated Bennett. There's probably a bit of Cukor magic in there, as well, though Bennett's huge eyes and twisted mouth should get a lot of credit for the combination of optimism, wisdom, and caution that drive this character. Mary is a great character, played to the hilt, and the script unabashedly cedes the entire picture to her; but even if that wasn't the case, I suspect Bennett would still make a huge impression thanks to the great worldliness she invests into the character - not just in the sense of sexual maturity, which is what "worldliness" too often means, but in an all-encompassing sense that she realises even before she has it how very contingent the stardom of a Hollywood celebrity is likely to be. The performance makes the film, and Cukor's ability to constantly frame scenes around her, even when they look like the most banal kind of wide conversation shots, helps give What Price Hollywood? an intense focus that goes even beyond what would automatically accrue to something with such a deliriously tight running time. It's a great character piece lying just atop a great snapshot of a particular place in a particular moment, and certainly one of my favorite semi-forgotten works of '30s American cinema.

Anyway, the price of Hollywood, we'll eventually learn, is that you're expected to sacrifice a bit of your inner self, to become an ideal in the minds of the fans and the newspapers, even if that means you don't have the luxury of being a person. The victim who'll be thrust through this process is one Mary Evans (Constance Bennett), who gets the full "only in Hollywood" treatment: a waitress/aspiring actress at the Brown Derby, she and her coworkers have an elaborate ecosystem of waiting on the various famous people who come to that legendary establishment, and Mary is able to barter her way into serving Max Carey (Lowell Sherman), a famous producer and infamous drunkard. In hardly any time, she's gotten a tiny part in a movie that impresses studio head Julius Saxe (Gregory Ratoff) that she's under contract and getting a big push as the newest star in the Hollywood firmament.

And I do mean "in hardly any time" - there are big and little problems with What Price Hollywood? to go with its big and little strengths, but the biggest problem is surely that it is in a real motherfucking hurry. The film is a mere 88 minutes, and it flies through them like a rocket. I get it, there's a lot to cover, but it seems like Mary goes from shrieking out her lines in a hugely unconvincing squeal to having an ad campaign designed around her in about 16 hours. Which is, in fact, about how long it takes, if you track the film's internal chronology, and even for a fluffy fantasy, that's pushing it.

Besides, this isn't a fluffy fantasy, which is one of the film's great strengths. It is a rarity in all the legions of Hollywood films about the Hollywood film industry, in that it indulges in neither the pie-eyed fairy stories of instant stardom and happy-minded people doing their gosh-darndest to make really swell pictures for the rest of us to enjoy (the Singin' in the Rain approach), nor the equally self-regarding vision of Hollywood as a uniquely cruel moral cesspit that destroys every good thing it touches (the Sunset Blvd. approach). Rather, What Price Hollywood? considers that the commercial film industry is, first and foremost, a commercial industry, and the people working inside of it, at least in 1932, were salaried professionals, not mercurial artists. The backstage stuff that makes up most of the first half of the movie is, I would go so far as to say, shockingly unromantic and unfussy in working through the nuts and bolts of how movies get made, and how helpless drunks like Max can go exactly this far in their drunkenness, as long as the movies get made. Even the big "star is born" moment, in which Mary nails a scene of being flirty and then horrified to see a dead body, isn't depicted as a flash of great actorly insight, but the end result of a long night in which she practices how to run up and down a flight of stairs.

Really, the same thing applies to its inevitable turn into various melodramatic streaks, the most prominent of which involves Mary falling into a somewhat acrimonious form of love with polo star Lonny Borden (Neil Hamilton), who is too much of a prig to understand the bonds of friendship that form between these *sniff* movie people. Unlike the four incarnations of A Star Is Born, this isn't really a love story; Lonny and his generally obnoxious behavior is just one more thing that Mary has to cope with as she discovers both the highs and lows of life in the public eye, and the film is much more interested in examining how the celebrity media latches onto the lives of movie stars as an occupational hazard than it is in depicting a moral tragedy.

An interesting, unexpected set of emphases provided by the litany of writers (two of whom, Adela Rogers St. Johns and Jane Murfin, picked up an Oscar nomination for Best Original Story), and even more so by director George Cukor, making the sixth feature of his legendary, long-lived career, and the first one that remains more or less alive in the awareness of all but the most single-minded cinephiles. It's a weird fit given what we know of the later Cukor, whose best work is pretty much exclusively in character-driven comedy, whereas this has only a little humor and most of that is pretty dark-minded; yet it's fair to say that the strengths of his work here lead directly into the strengths of his exemplary career. Cukor was one of the great directors of actors - of women in particular, but he certainly does fine by Lowell Sherman in this case - foreground dialogues as the most visually interesting part of even the busiest frame. And there are some fine frames here, and a remarkably acute sense of place - 1932 was just about the earliest year of the sound era in which a camera could move so comfortably around the world, and while the film's exploration of Los Angeles is hardly a long trip, there are scenes that certainly benefit from an unexpected dash of realism, by '32 standards.

But what the film is really about is never the interior spaces swallowing up the characters, as was sometimes the case in Cukor's 1954 take on similar material, in A Star Is Born v2.0. It's always the characters themselves, however framed and packaged by their surroundings, and no matter how wide Cukor and his cinematographer, the great Charles Rosher, set their camera (and it can be awfully wide, particularly on the movie sets). The blocking always drives us towards the characters, and particularly Mary, the best performance in the great career of the deeply under-appreciated Bennett. There's probably a bit of Cukor magic in there, as well, though Bennett's huge eyes and twisted mouth should get a lot of credit for the combination of optimism, wisdom, and caution that drive this character. Mary is a great character, played to the hilt, and the script unabashedly cedes the entire picture to her; but even if that wasn't the case, I suspect Bennett would still make a huge impression thanks to the great worldliness she invests into the character - not just in the sense of sexual maturity, which is what "worldliness" too often means, but in an all-encompassing sense that she realises even before she has it how very contingent the stardom of a Hollywood celebrity is likely to be. The performance makes the film, and Cukor's ability to constantly frame scenes around her, even when they look like the most banal kind of wide conversation shots, helps give What Price Hollywood? an intense focus that goes even beyond what would automatically accrue to something with such a deliriously tight running time. It's a great character piece lying just atop a great snapshot of a particular place in a particular moment, and certainly one of my favorite semi-forgotten works of '30s American cinema.