Hammer Horror: Weird science

Robert Louis Stevenson's 1886 novella The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde presents a unique challenge to the filmmaking team that wants to adapt it for the big screen. It's hugely well-known by the standards of 19th Century (i.e., public domain) genre fiction, so clearly not adapting it is no kind of option; but the thing it's best known for is a twist ending, and it would be impossible or at least very ill-advised to use the story in anything resembling the way Stevenson wrote it. So any screen incarnation of the story of Dr. Henry Jekyll and the formula that transforms him into the cruel, rapacious Mr. Edward Hyde is going to have to invent pretty much everything.

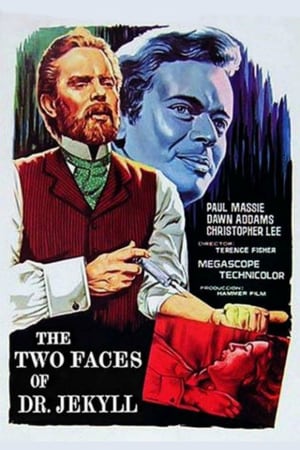

Historically, this has been handled in all sorts of different ways, including softcore pornography and broad comedy, but one of the best and boldest versions was the adaptation made by Hammer Film Productions in 1960, The Two Faces of Dr. Jekyll. By this time, Hammer had mostly completed its transition to an horror-focused studio: there had been two Frankenstein films, two Dracula films, and The Mummy already when the studio's second Jekyll & Hyde picture was released. Given the very clear "widescreen Technicolor remakes of classic Hollywood horror films" vibe established by that list, the appeal of a Hammerfied version of the 1931 Paramount Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde and its 1941 MGM remake is pretty damn clear; Wolf Mankowitz's screenplay takes full advantage of Hammer's new reputation as purveyors of the most viciously violent, tawdrily sexual stuff that the British censors would even dream of letting into theaters - it is certainly more overtly sexed-up than anything else Hammer had made to that point, more sexed-up than any film version of the story I can name, and the sex is very much part and parcel of what makes this, after the '31 film, my all-time favorite adaptation of the novel.

You will maybe notice that I called this the second Hammer Jekyll & Hyde project. The first came out a bit more than a year prior to The Two Faces of Dr. Jekyll, in August 1959, under the title of The Ugly Duckling, and in its little way, it's even bolder than the 1960 film, for it does some of the same things, but it did them first, and it's also a full-comedy. It is possibly the first film version of this material to take the approach of making the Hyde version of the character not just antisocial and immoral, but also more attractive and slutty. That's the approach that Two Faces took as well, and then three years after that the Jerry Lewis vehicle The Nutty Professor, and we could go on, but it's not actually the point. The point is that considering Hyde to be the more sexually charismatic version of Jekyll is an awfully striking thing to do with this material, and it gets right to the heart of what Two Faces is playing at that makes it such a special entry in the annals of Jekyll & Hyde movies.

Unlike other versions of this story, our present Henry Jekyll (Paul Massie) isn't a moral crusader looking to free humankind from its vices; nor is he just a wide-eyed naïve scientist who's just following his ideas until they get him into trouble. He's not even, at first, a hypocritical hedonist trying to preserve his fine social appearance by funneling all of his depravity into an alter-ego. He's something less human than any of that, a scientist and moralist so devoted to ideas that he seems to have forgotten that we can feel anything in the first place, the kind of person whose banal objectivity leads him to refer a group of mute schoolchildren (warmly, which makes it worse) as "dumb human animals", and this is literally the first thing we hear him say. For this Jekyll, his research has nothing to do with good or evil; indeed, the phrase "beyond good and evil" comes out of his mouth not too long after "dumb human animals" does. His research is just about isolating the patterns of brain chemistry that encourage hedonism in the interest of crushing it down and replacing it with pure, cold reason.

This is all to say, this film's Edward Hyde isn't just the "evil" Jekyll (though there's no doubt at all on the film's part that Hyde commits evil, and only evil - he is never appealing to us, we only see why the other characters might find him appealing); in a queasy-making way, he's also the "human" Jekyll. That leads to some bitter implications, and a film more or less without morality; a shocking thing to find in this most moralistic of late-Victorian genre stories. The result is a film that's got a nasty streak even by Hammer standards; for most of the studio's output, the shrieking moral outrage seems to be, half a century later and more, just a bunch of prim English ninnies who couldn't handle a little blood and cleavage. But with Two Faces, there's a truly sordid feeling that hasn't dissipated entirely even though the moment of this film's creation has long since given way to a wholly different set of filmmaking attitudes. There are no "good" characters - Jekyll's wife, Kitty (Dawn Addams), is having an affair with his friend Paul Allen (Christopher Lee), presumably because Jekyll is so very clearly an emotionless prig; Paul, for his part, is completely dissolute and penniless, relying on the generous doctor's checkbook to keep his own licentiousness financed. The chief object of Hyde's increasingly unpleasant affections is Maria (Norma Marla), a prostitute like in so many versions of the story; but she's not a glowing, virginal prostitute in the Ingrid Bergman model, but just a working girl who doesn't think much of her job one way or the other, from what we can tell.

The film's startling frankness in depicting all of this, far beyond anything that makes remote sense for a commercially-viable 1960 release in the English-speaking world, gives the film most of its tone, which is miles away from the heavy Gothic menace of the earlier Hammer horror films. Indeed, The Two Faces of Dr. Jekyll is so light and airy in its visuals that it almost feels disingenuous to call it "horror" at all. Not to mention the relative buoyancy of the performances; Lee, playing a smarmy rogue, is having an obvious blast getting away from all those snarling monsters, and his Paul is easy and winning, making it easy to see why people would like him even though he transparently adds nothing of value to the world. Addams's Kitty is one of the few altogether interesting women in any Hammer production, as well as probably the closest this film has to a sympathetic character, and Addams and Lee have real chemistry together that helps make their subplot feel emotionally rich rather than just tawdry.

As is invariably the case in films on this narrative model, though, Massie has to do all of the work, and while he's not a natural screen presence of Lee's magnitude, he makes it happen. Among the film's unusual approaches to the material, we have here a film in which the actor wears heavy make-up to play the older Jekyll, while his Hyde is just Massie's own face. This has two immediate effects. One is to limit the depth of anything that Massie can invest into Jekyll, since he looks frankly goofy, and there's not much that can be done about that, even setting aside the fact that it apparently leaves the actor's facial muscles pinned down. So Jekyll ends up feeling stiff and insincere and quite empty, which helps add to the film's treatment of the character. The other is that Hyde has the smoothly handsome looks of a matinee idol, and Massie and director Terence Fisher lean into that: the latter by constantly framing Massie's face to occupy the center of all his dialogue scenes and leaving the actor plenty of close-ups, the latter by foregrounding the cheerfulness of his Hyde, carried off with insouciance and a very impish smile that almost begs you to ask to be let in on the secret. This is a happy monster, not a raging one, and even as he beats and rapes and murders, he seems to be very pleased with himself. It ends up being so much more unnerving and scary than the more openly ape-like, animalistic Hydes of most screen performances that for the only time in the character's cinematic career, he seems genuinely dangerous.

That feeling of danger ties into the overall sense that the film is getting away with something, with that frank sexuality and general vibe of amorality, and that helps to carry the film over any problems that crop up along the way. It's by no means the smoothest of Hammer's horror films, and it notably lacks much in the way of atmosphere: Victorian London is presumably a less interesting place to light and design than some rotting castle in northern Europe, and Fisher is distinctly less invested in creating atmosphere than in his best work for Hammer. Indeed, the club where most of the action takes place is a frankly boring, everyday-looking place, which isn't necessarily to the film's detriment - it adds to the sense that something truly awful has been born out of merely quotidian debauchery.

Add to that the ridiculous contrivances of the last act (which involve, among other improbably melodramatic flourishes, a man being poisoned to death by a non-venomous constrictor), and there's little room to argue that Two Faces is an achievement at the level of e.g. The Curse of Frankenstein. Even so, and despite liking the thick Gothic presence that is otherwise the most important part of every great Hammer production, I do think this is one of the top-shelf Hammer horror films, and probably the most perpetually undervalued, for reasons that I've never been able to figure out. Possibly the fact that it's not really very eager to flaunt its genre credentials is part of it; it also got hit harder by critics at the time than its predecessors. Whatever the case, and despite Fisher's evident detachment from the material, this is surely one of the most interestingly warped and perverse Hammer movies, blessed by a wholly insidious screenplay (the only one that Mankowitz wrote for the studio) and unusually consistent acting across the board for a Hammer film, and its relative invisibility among the Hammer horror films is a tremendous irritation to me.

Historically, this has been handled in all sorts of different ways, including softcore pornography and broad comedy, but one of the best and boldest versions was the adaptation made by Hammer Film Productions in 1960, The Two Faces of Dr. Jekyll. By this time, Hammer had mostly completed its transition to an horror-focused studio: there had been two Frankenstein films, two Dracula films, and The Mummy already when the studio's second Jekyll & Hyde picture was released. Given the very clear "widescreen Technicolor remakes of classic Hollywood horror films" vibe established by that list, the appeal of a Hammerfied version of the 1931 Paramount Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde and its 1941 MGM remake is pretty damn clear; Wolf Mankowitz's screenplay takes full advantage of Hammer's new reputation as purveyors of the most viciously violent, tawdrily sexual stuff that the British censors would even dream of letting into theaters - it is certainly more overtly sexed-up than anything else Hammer had made to that point, more sexed-up than any film version of the story I can name, and the sex is very much part and parcel of what makes this, after the '31 film, my all-time favorite adaptation of the novel.

You will maybe notice that I called this the second Hammer Jekyll & Hyde project. The first came out a bit more than a year prior to The Two Faces of Dr. Jekyll, in August 1959, under the title of The Ugly Duckling, and in its little way, it's even bolder than the 1960 film, for it does some of the same things, but it did them first, and it's also a full-comedy. It is possibly the first film version of this material to take the approach of making the Hyde version of the character not just antisocial and immoral, but also more attractive and slutty. That's the approach that Two Faces took as well, and then three years after that the Jerry Lewis vehicle The Nutty Professor, and we could go on, but it's not actually the point. The point is that considering Hyde to be the more sexually charismatic version of Jekyll is an awfully striking thing to do with this material, and it gets right to the heart of what Two Faces is playing at that makes it such a special entry in the annals of Jekyll & Hyde movies.

Unlike other versions of this story, our present Henry Jekyll (Paul Massie) isn't a moral crusader looking to free humankind from its vices; nor is he just a wide-eyed naïve scientist who's just following his ideas until they get him into trouble. He's not even, at first, a hypocritical hedonist trying to preserve his fine social appearance by funneling all of his depravity into an alter-ego. He's something less human than any of that, a scientist and moralist so devoted to ideas that he seems to have forgotten that we can feel anything in the first place, the kind of person whose banal objectivity leads him to refer a group of mute schoolchildren (warmly, which makes it worse) as "dumb human animals", and this is literally the first thing we hear him say. For this Jekyll, his research has nothing to do with good or evil; indeed, the phrase "beyond good and evil" comes out of his mouth not too long after "dumb human animals" does. His research is just about isolating the patterns of brain chemistry that encourage hedonism in the interest of crushing it down and replacing it with pure, cold reason.

This is all to say, this film's Edward Hyde isn't just the "evil" Jekyll (though there's no doubt at all on the film's part that Hyde commits evil, and only evil - he is never appealing to us, we only see why the other characters might find him appealing); in a queasy-making way, he's also the "human" Jekyll. That leads to some bitter implications, and a film more or less without morality; a shocking thing to find in this most moralistic of late-Victorian genre stories. The result is a film that's got a nasty streak even by Hammer standards; for most of the studio's output, the shrieking moral outrage seems to be, half a century later and more, just a bunch of prim English ninnies who couldn't handle a little blood and cleavage. But with Two Faces, there's a truly sordid feeling that hasn't dissipated entirely even though the moment of this film's creation has long since given way to a wholly different set of filmmaking attitudes. There are no "good" characters - Jekyll's wife, Kitty (Dawn Addams), is having an affair with his friend Paul Allen (Christopher Lee), presumably because Jekyll is so very clearly an emotionless prig; Paul, for his part, is completely dissolute and penniless, relying on the generous doctor's checkbook to keep his own licentiousness financed. The chief object of Hyde's increasingly unpleasant affections is Maria (Norma Marla), a prostitute like in so many versions of the story; but she's not a glowing, virginal prostitute in the Ingrid Bergman model, but just a working girl who doesn't think much of her job one way or the other, from what we can tell.

The film's startling frankness in depicting all of this, far beyond anything that makes remote sense for a commercially-viable 1960 release in the English-speaking world, gives the film most of its tone, which is miles away from the heavy Gothic menace of the earlier Hammer horror films. Indeed, The Two Faces of Dr. Jekyll is so light and airy in its visuals that it almost feels disingenuous to call it "horror" at all. Not to mention the relative buoyancy of the performances; Lee, playing a smarmy rogue, is having an obvious blast getting away from all those snarling monsters, and his Paul is easy and winning, making it easy to see why people would like him even though he transparently adds nothing of value to the world. Addams's Kitty is one of the few altogether interesting women in any Hammer production, as well as probably the closest this film has to a sympathetic character, and Addams and Lee have real chemistry together that helps make their subplot feel emotionally rich rather than just tawdry.

As is invariably the case in films on this narrative model, though, Massie has to do all of the work, and while he's not a natural screen presence of Lee's magnitude, he makes it happen. Among the film's unusual approaches to the material, we have here a film in which the actor wears heavy make-up to play the older Jekyll, while his Hyde is just Massie's own face. This has two immediate effects. One is to limit the depth of anything that Massie can invest into Jekyll, since he looks frankly goofy, and there's not much that can be done about that, even setting aside the fact that it apparently leaves the actor's facial muscles pinned down. So Jekyll ends up feeling stiff and insincere and quite empty, which helps add to the film's treatment of the character. The other is that Hyde has the smoothly handsome looks of a matinee idol, and Massie and director Terence Fisher lean into that: the latter by constantly framing Massie's face to occupy the center of all his dialogue scenes and leaving the actor plenty of close-ups, the latter by foregrounding the cheerfulness of his Hyde, carried off with insouciance and a very impish smile that almost begs you to ask to be let in on the secret. This is a happy monster, not a raging one, and even as he beats and rapes and murders, he seems to be very pleased with himself. It ends up being so much more unnerving and scary than the more openly ape-like, animalistic Hydes of most screen performances that for the only time in the character's cinematic career, he seems genuinely dangerous.

That feeling of danger ties into the overall sense that the film is getting away with something, with that frank sexuality and general vibe of amorality, and that helps to carry the film over any problems that crop up along the way. It's by no means the smoothest of Hammer's horror films, and it notably lacks much in the way of atmosphere: Victorian London is presumably a less interesting place to light and design than some rotting castle in northern Europe, and Fisher is distinctly less invested in creating atmosphere than in his best work for Hammer. Indeed, the club where most of the action takes place is a frankly boring, everyday-looking place, which isn't necessarily to the film's detriment - it adds to the sense that something truly awful has been born out of merely quotidian debauchery.

Add to that the ridiculous contrivances of the last act (which involve, among other improbably melodramatic flourishes, a man being poisoned to death by a non-venomous constrictor), and there's little room to argue that Two Faces is an achievement at the level of e.g. The Curse of Frankenstein. Even so, and despite liking the thick Gothic presence that is otherwise the most important part of every great Hammer production, I do think this is one of the top-shelf Hammer horror films, and probably the most perpetually undervalued, for reasons that I've never been able to figure out. Possibly the fact that it's not really very eager to flaunt its genre credentials is part of it; it also got hit harder by critics at the time than its predecessors. Whatever the case, and despite Fisher's evident detachment from the material, this is surely one of the most interestingly warped and perverse Hammer movies, blessed by a wholly insidious screenplay (the only one that Mankowitz wrote for the studio) and unusually consistent acting across the board for a Hammer film, and its relative invisibility among the Hammer horror films is a tremendous irritation to me.