Universal Horror: The Price of invisibility

1940's The Invisible Man Returns is just about the last of Universal Pictures' classic horror movies that can unequivocally be called an A-picture. The studio's other genre films from the same calendar year, Black Friday and The Mummy's Hand, were made for a fraction of its budget and with nowhere near the same care and attention to artistry; 1941's The Wolf Man straddles the A/B divide, and bears more similarities to the unabashed B-movies to follow than otherwise; the next two "Invisible" pictures were both made for as high a budget as Universal was apt to spend on anything tinged with genre, but neither of them is even superficially within the purview of horror.

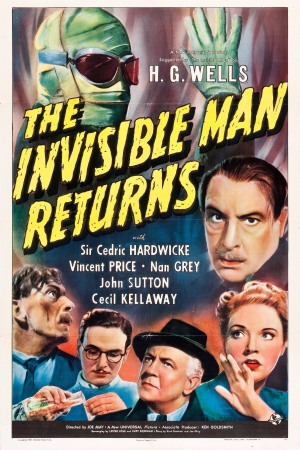

So this is it, then: the last true flowering of the great Golden Age of Universal horror, and what do you know, The Invisible Man Returns even manages to do right by the considerable pressure that status places upon it. It's one of the most thoughtful sequels the studio made to any of their horror films, coming up with a genuinely reasonable way to extend the story set forth in The Invisible Man from 1933 (the credits make the bolder claim that this is sequel to H.G. Wells's original novel) that goes out of its way to avoid replicating the plot structure of the original. Not even the studio's all-time best sequel, Bride of Frankenstein, can make that claim. Hell, The Invisible Man Returns is just about a perfect reversal of the original movie, replacing that film's soon-to-be-cliché tale of an arrogant mad scientist turned into a monster out of his own sense of superiority to normal people with a tragic story of an innocent who is, through not fault of his own, transformed into a dangerous threat, while simultaneously trying to solve the mystery of who framed him for murder.

The story is initially presented in a slightly patchy way, the better to keep us in the dark as long as possible before letting its secrets to light (for all its many charms, The Invisible Man Returns is actually kind of lousy as a mystery, and this unnecessary structural sleight-of-hand is among the reasons why). The opening scene is a locked room mystery: Geoffrey Radcliffe, sentenced to be hanged for the crime of murdering his brother Michael, has vanished from his cell, leaving behind nothing but a pile of clothes. That and the title are enough to give us a good sense of what's going on, and uniquely in the annals of horror, it gives the cops a good sense, too: Inspector Sampson (Cecil Kellaway) of Scotland Yard goes straight to Dr. Frank Griffin (John Sutton), a friend of the missing Geoffrey and the brother of the late Dr. Jack Griffin, who was involved in some great unpleasantness involving a madness-inducing invisibility serum nine years prior. All of this is recapped in a terrific piece of expository screenwriting, in which the usual "let's repeat the plot of the last movie and also mention details that we both already know" fiddle-faddle is transformed into a character beat, with Sampson needling Griffin in the haughty way of all movie cops who know the score but are helpless until they can prove it.

Geoffrey, of course has been turned invisible, and is presently roaming England on the hunt to find out who framed him; his disembodied voice and occasionally his banadage-wrapped body are played by the great Vincent Price, in only the second horror movie of his young career (this was his fourth feature overall; it would be well more than a decade before he became noted as a horror star first and foremost). In addition to Griffin, Geoffrey is helped out by his girlfriend Helen Manson (Nan Grey), though neither of them are able to much in the way of assistance beyond fretting that the chemicals which drove Jack Griffin to psychopathic insanity are going to start working on Geoffrey pretty soon if a way to reverse the procedure doesn't show up. Also fretting over Geoffrey's fate is one Richard Cobb (Sir Cedric Hardwicke), a close friend of the Radcliffe brothers who has taken over their coal mining operation ever since Michael's death and Geoffrey's imprisonment. His concern, of course, is of a rather less friendly, affectionate kind than Helen's, particularly when newly-minted mining foreman Willie Spears (Alan Napier) reveals that Cobb is more than just the lucky beneficiary of a horrible series of developments, but that he in fact engineered the whole shebang.

Not a reveal I expected to show up anywhere remotely near as early as it did, and why screenwriters Joe May (who also directed) and Curt Siodmak (credited under "Kurt", but still the genius responsible for most of the best American horror scripts of the '40s) decided to go that route genuinely baffles me. It's not like the film suddenly becomes a Hitchcockian thriller on the lines of Vertigo as a result of the reveal, and it leaves the vestigial structure of a mystery in place without any mystery to solve for something like half of the running time. What May correctly intuits is that airtight plotting is maybe not as important as breathless momentum - this is a much busier film than The Invisible Man, with a surprisingly twisty plot that I haven't outlined in more than just its broad strokes, and the film moves through that plot at a relentless speed - and splendid visual effects, which really are just the best damn thing here. The visual effects in 1933 film have aged well in their own right, but its first sequel roundly surpasses it in every way visual effects can be surpassed.

Part of the trick, I think, is that the sequel knows it can't rely on the sheer awe-inspiring potency of the invisibility effect itself, since the seven-year-old Invisible Man had largely exhausted those possibilities. So even more than in the first film, the effects are used to accentuate the story, and not just to wow us. And this emphasis on the storytelling aspects helps the film glide over the stickier patches. One of the film's most delightful scenes finds Griffin attempting to restore an invisible guinea pig, and no, I can't imagine anybody watching the film in 2015 (or in 1940) not immediately spotting the seams. On the other hand, the earnestness with which May and Sutton commit to selling that little mechanised harness as an invisible guinea pig makes it a playful moment, not a failed illusion.

Playfulness is at the heart of all of the film's best moments, in fact. That's what comes from getting Vincent Price in your movie, undoubtedly - his performance isn't as confident and demanding as Claude Rains, though it benefits from vastly superior sound mixing technology, and his voice hadn't developed into the effete sarcasm that we all know and love him for. But his future slyness and hammy wit are completely in place: there's a scene where the invisible Geoffrey pretends to be a ghost to scare Spears into a confession, and it's the exact mixture of charming, hokey, and dismissive that marks the best of latter-day Price.

What this does suggest, fairly, is that The Invisible Man Returns is generally a less high-impact film than The Invisible Man. Price is a sardonic charmer, but Rains was a menacing bully; May has a good sense of pacing and convincing us of the reality of an effect, but James Whale had that and an intuitive sense of how to frame even the most innocuous scene to be heavy with brooding atmosphere. The Invisible Man Returns is less of a movie than its predecessor; or, at least, less of a horror movie. It lacks a dangerous edge. What it has instead is awfully appealing, though: a creative expansion on the original's story that uses the same hook to significantly different, more humane ends, and three terrific performances from Price, Kellaway, and Hardwicke. The abbreviated atmosphere is all it takes to keep it a step down from the truly great Universal horror films, but this film still deserves a hell of a lot more respect than it has gotten, relative to its stablemates.

Reviews in this series

The Invisible Man (Whale, 1933)

The Invisible Man Returns (May, 1940)

The Invisible Woman (Sutherland, 1940)

Invisible Agent (Marin, 1942)

The Invisible Man's Revenge (Beebe, 1944)

Abbott and Costello Meet the Invisible Man (Lamont, 1951)

So this is it, then: the last true flowering of the great Golden Age of Universal horror, and what do you know, The Invisible Man Returns even manages to do right by the considerable pressure that status places upon it. It's one of the most thoughtful sequels the studio made to any of their horror films, coming up with a genuinely reasonable way to extend the story set forth in The Invisible Man from 1933 (the credits make the bolder claim that this is sequel to H.G. Wells's original novel) that goes out of its way to avoid replicating the plot structure of the original. Not even the studio's all-time best sequel, Bride of Frankenstein, can make that claim. Hell, The Invisible Man Returns is just about a perfect reversal of the original movie, replacing that film's soon-to-be-cliché tale of an arrogant mad scientist turned into a monster out of his own sense of superiority to normal people with a tragic story of an innocent who is, through not fault of his own, transformed into a dangerous threat, while simultaneously trying to solve the mystery of who framed him for murder.

The story is initially presented in a slightly patchy way, the better to keep us in the dark as long as possible before letting its secrets to light (for all its many charms, The Invisible Man Returns is actually kind of lousy as a mystery, and this unnecessary structural sleight-of-hand is among the reasons why). The opening scene is a locked room mystery: Geoffrey Radcliffe, sentenced to be hanged for the crime of murdering his brother Michael, has vanished from his cell, leaving behind nothing but a pile of clothes. That and the title are enough to give us a good sense of what's going on, and uniquely in the annals of horror, it gives the cops a good sense, too: Inspector Sampson (Cecil Kellaway) of Scotland Yard goes straight to Dr. Frank Griffin (John Sutton), a friend of the missing Geoffrey and the brother of the late Dr. Jack Griffin, who was involved in some great unpleasantness involving a madness-inducing invisibility serum nine years prior. All of this is recapped in a terrific piece of expository screenwriting, in which the usual "let's repeat the plot of the last movie and also mention details that we both already know" fiddle-faddle is transformed into a character beat, with Sampson needling Griffin in the haughty way of all movie cops who know the score but are helpless until they can prove it.

Geoffrey, of course has been turned invisible, and is presently roaming England on the hunt to find out who framed him; his disembodied voice and occasionally his banadage-wrapped body are played by the great Vincent Price, in only the second horror movie of his young career (this was his fourth feature overall; it would be well more than a decade before he became noted as a horror star first and foremost). In addition to Griffin, Geoffrey is helped out by his girlfriend Helen Manson (Nan Grey), though neither of them are able to much in the way of assistance beyond fretting that the chemicals which drove Jack Griffin to psychopathic insanity are going to start working on Geoffrey pretty soon if a way to reverse the procedure doesn't show up. Also fretting over Geoffrey's fate is one Richard Cobb (Sir Cedric Hardwicke), a close friend of the Radcliffe brothers who has taken over their coal mining operation ever since Michael's death and Geoffrey's imprisonment. His concern, of course, is of a rather less friendly, affectionate kind than Helen's, particularly when newly-minted mining foreman Willie Spears (Alan Napier) reveals that Cobb is more than just the lucky beneficiary of a horrible series of developments, but that he in fact engineered the whole shebang.

Not a reveal I expected to show up anywhere remotely near as early as it did, and why screenwriters Joe May (who also directed) and Curt Siodmak (credited under "Kurt", but still the genius responsible for most of the best American horror scripts of the '40s) decided to go that route genuinely baffles me. It's not like the film suddenly becomes a Hitchcockian thriller on the lines of Vertigo as a result of the reveal, and it leaves the vestigial structure of a mystery in place without any mystery to solve for something like half of the running time. What May correctly intuits is that airtight plotting is maybe not as important as breathless momentum - this is a much busier film than The Invisible Man, with a surprisingly twisty plot that I haven't outlined in more than just its broad strokes, and the film moves through that plot at a relentless speed - and splendid visual effects, which really are just the best damn thing here. The visual effects in 1933 film have aged well in their own right, but its first sequel roundly surpasses it in every way visual effects can be surpassed.

Part of the trick, I think, is that the sequel knows it can't rely on the sheer awe-inspiring potency of the invisibility effect itself, since the seven-year-old Invisible Man had largely exhausted those possibilities. So even more than in the first film, the effects are used to accentuate the story, and not just to wow us. And this emphasis on the storytelling aspects helps the film glide over the stickier patches. One of the film's most delightful scenes finds Griffin attempting to restore an invisible guinea pig, and no, I can't imagine anybody watching the film in 2015 (or in 1940) not immediately spotting the seams. On the other hand, the earnestness with which May and Sutton commit to selling that little mechanised harness as an invisible guinea pig makes it a playful moment, not a failed illusion.

Playfulness is at the heart of all of the film's best moments, in fact. That's what comes from getting Vincent Price in your movie, undoubtedly - his performance isn't as confident and demanding as Claude Rains, though it benefits from vastly superior sound mixing technology, and his voice hadn't developed into the effete sarcasm that we all know and love him for. But his future slyness and hammy wit are completely in place: there's a scene where the invisible Geoffrey pretends to be a ghost to scare Spears into a confession, and it's the exact mixture of charming, hokey, and dismissive that marks the best of latter-day Price.

What this does suggest, fairly, is that The Invisible Man Returns is generally a less high-impact film than The Invisible Man. Price is a sardonic charmer, but Rains was a menacing bully; May has a good sense of pacing and convincing us of the reality of an effect, but James Whale had that and an intuitive sense of how to frame even the most innocuous scene to be heavy with brooding atmosphere. The Invisible Man Returns is less of a movie than its predecessor; or, at least, less of a horror movie. It lacks a dangerous edge. What it has instead is awfully appealing, though: a creative expansion on the original's story that uses the same hook to significantly different, more humane ends, and three terrific performances from Price, Kellaway, and Hardwicke. The abbreviated atmosphere is all it takes to keep it a step down from the truly great Universal horror films, but this film still deserves a hell of a lot more respect than it has gotten, relative to its stablemates.

Reviews in this series

The Invisible Man (Whale, 1933)

The Invisible Man Returns (May, 1940)

The Invisible Woman (Sutherland, 1940)

Invisible Agent (Marin, 1942)

The Invisible Man's Revenge (Beebe, 1944)

Abbott and Costello Meet the Invisible Man (Lamont, 1951)

Categories: horror, mysteries, science fiction, thrillers, universal horror, worthy sequels