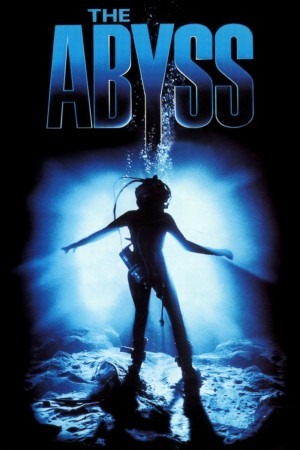

James Cameron Retrospective: The abyss stares back

Having completed his meteoric rise to become one of Hollywood's biggest popcorn-movie filmmakers in just a handful of years, so that only three films into his career his fourth film could be breezily advertised as "from the director of The Terminator and Aliens", James Cameron set his sights on his most ambitious project yet, an underwater science-fiction epic that allowed him to indulge his years-long fascination with deep-sea exploration while playing around with his beloved theme of everyday Joe action heroes and continuing his attempts to exploit the snazziest new visual effects technology that he could get his hands on. The result, The Abyss, was one of the most expensive films released in the famous summer of 1989, widely regarded as the most crowded summer for blockbusters ever, even in these days when every new Friday between May 1 and August 15 seems to have a new $100 million dollar premiere.

At the time, Cameron's film was one of the poor bastards that had to give way to the onslaught of the likes of Batman and Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade, and depending on whose budget estimate you listen to ($70 million is usually considered authoritative), the film only barely eked out a profit on international sales - given advertising, it seems likely to assume that it lost money. Time has been fairly kind to it, owing no doubt to fanboyism and the director's rather good-sized following, but one not be a Cameron acolyte to recognise that The Abyss has aged better than some of the films that outshone it back in the day - quick, who wants to take in a double feature of Parenthood and Turner & Hooch? - even as we must all probably concede that it isn't nearly the achievement of its two predecessors, nor his next project, an ill-advised Terminator sequel that ended up being one of the best American action movies of the 1990s. But I'm not here to bury The Abyss, but to praise it as a fairly brainier sci-fi action flick than we're typically used to.

Ah, but which Abyss do I mean? For in the case of this particular film, the "extended cut" issue raises its thorny head in a far more difficult case than we had with Aliens, or with the great majority of special edition edits. In Aliens, as you recall, most of the scenes added had an invisible quality, adding bits of character detail without affecting the plot. There are really only two points of particular significance: the addition of Ripley's dead grown-up daughter, giving a boost to her relationship with the orphan girl Newt; and the poor decision (in my opinion) to add a scene on the space colony before its fall. But these really only augment the Aliens that already exists. This is, of course, the nature of most such cuts: the same movie has a bit more info and hopefully a bit more impact, but it is the same movie.

Not so with The Abyss. 20th Century Fox Home Video has very carefully never called their 1993 version of the film a "Director's Cut", and I do not know James Cameron's particular opinion on the matter; I do know that he had final cut on the movie as long as it was within a certain running time, so perhaps he left certain particular moments on the cutting room floor to ensure that he'd get the rest of the movie exactly how he wanted it. I also know that the 1993 version of The Abyss, running 28 minutes longer (and three minutes of extra end credits) than the 140 minute theatrical cut, is in essence not the same movie as the theatrical cut. I don't mean that in some high-falutin' "to change even one frame is to change the movie entire" film theory way. I mean, literally, that the 171 minute Abyss tells a materially different story than the 140 minute Abyss, and for my tastes, it tells a much, much better story at that; it's one of those rare cases where adding footage makes the thing feel shorter, for all the new footage clicks so well and adds a richness that the original lacked.

In either case, The Abyss tells of the crew of an Deep Core 2, an experimental deep-sea oil platform in the Bahamas, who are contracted by the U.S. Navy to aid in the salvage of a nuclear submarine that went down under mysterious circumstances - the audience knows more than the government, in that we saw the strange blue and pink light that caused the ship to lose its power, but at this point we're even pretty well left in the dark. The leader of the drillers is Bud Brigman (Ed Harris), a rock-solid blue collar type, who isn't terribly keen to have a mirthless SEAL by the name of Coffey (Michael Biehn, in his last film with Cameron) ordering him around, but he likes his job too much to complain. In this he is quite altogether less passionate than his estranged wife Lindsey (Mary Elizabeth Mastrantonio), the designer of the deep-sea rig, who has quite the possessive, protective view of her baby, and doesn't care to see a bunch of rough military types banging it about.

Once the SEALS get down to Deep Core, the story - either variant of it - proceeds in a vaguely plotless direction, watching as the men (and two women) go about their chores in fairly close, even documentary-esque detail, allowing for the fact that The Abyss presents a completely fictional situation, so the word "documentary" is horribly inapt. Bud and Coffey butt heads over leadership, the crew operates machines and goes diving in the wreck of the sub, and strange events keep happening: first, inside the downed vessel, one of the drillers, Jammer (John Bedford Lloyd) sees something pink and blue that startles him so much that he hyperventilates himself into a coma; later, Lindsey twice spots some kind of inexplicable objects that look a bit like translucent plastic sea beasts, but glow and cause power failures in nearby electronic objects. As all this is happening, a major crisis looms: due to the hurricane up top, the rig has been dragged to the very edge of an unfathomably deep abyss, and in the process was damaged enough that it's taken on water, and both the heating and oxygen systems have taken a hit - if the crew can't figure out how to fix things, they'll be freezing in four hours, and suffocating in well under a day. Not to mention that Coffey is starting to suffer from psychosis, brought on by pressurization sickness; and damn it all, but he's the one in charge of the guns.

The difference between the two cuts throughout this passage (the first 100 minutes of the theatrical cut, the first two hours of the extended version) is largely one of tone: in both cases, there's a certain stretched-out observational feel that suggests, especially considering what happens later, that Cameron was trying to make his very own 2001: A Space Odyssey (that Stanley Kubrick film was also visually referenced several times in Aliens), following with a certain detachment as people try to go about their very high-tech business as Something Paranormal is flitting about just where you can't see it, but the extended cut benefits from stretching out the stretching-out with a bevy of added character details. In the original version, the crew of the rig has the bland uniformity of any blue-collar team of heroes, all identified by nicknames like Catfish (Leo Burmester) and One Night (Kimberly Scott) and Hippy (Todd Graff), and defined by one personality trait and their job; they are not even as distinct as the Central Casting marines in Aliens. But the little extensions of scenes add a good deal of depth and personality to virtually every one of the characters, and give us a far better sense of Bud and Lindsey's broken marriage, and what that break has cost each of them. There's also one big scene added entirely new, one that adds quite a bit to the character of the drillers: as One Night pilots the Flatbed (basically, the tow-ship used to move the rig about), she listens to Linda Ronstadt's trucker anthem "Willing", and as a couple other characters hear it on the intercom, they start to sing along. It's a sweet little moment that shows the extended family tightness of the crew, and allows us to see what exactly Cameron - a former truck driver, we must not forget - was aiming at in his depiction of these rough workers.

Not that the theatrical cut is without its nuanced little moments: one of the best parts of either cut is the detail of Bud's wedding ring, which he throws in a chemical toilet after fighting with Lindsey (though the extended cut explains this fight better); when he fishes it out a moment later, it stains his hand blue, and that stain is present for the rest of the film, a vivid but never overbearing detail that constantly reminds us of his personal stakes throughout the piece. It is a bit disingenuous to speak of any James Cameron film in terms of the richness of its characterisations, but at the same time he doesn't scrimp in that area like a lot of similar filmmakers: consider Michael Bay's Armageddon, with its army of writers, that also takes a look at a team of oil drillers but can't be arsed to come up with even a fraction of the sympathetic representation that Cameron whipped up all on his own.

Along the way, we get treated to a lot of really nifty setpieces, evidence of the director's intense love of well-crafted spectacle: the absurd amount of underwater photography and scenes in flooded interiors (largely without stunt doubles!) may have made the film a living hell to shoot for everyone concerned - Mastrantonio supposedly suffered a nervous breakdown in the middle of shooting, which probably led to her vocal objections to the amount of good footage snipped out of the theatrical cut - but it resulted in a rather enjoyable summer movie, full of chaotic, exciting incident that never reaches down to the condescending depths of so very many of the films in that mold that have seen release in the last 20 years. The Abyss might have had an absurd price tag in terms in both financial and human terms, but you cannot say that we don't see that $70 million on the screen, in all of the fantastic underwater footage, great models, and most notably, a really stunning and groundbreaking use of CGI courtesy of Industrial Light and Magic, bringing to life a semi-sentient tentacle of water snaking through Deep Core - it was, after Willow, only the second use of CGI morphing in cinema history, and what was insanely cool in 1989 still holds up exceedingly well today - am I alone in noticing that computer-generated effects in the early years, such as here, or in Terminator 2 or Jurassic Park, look infinitely more convincing than the effects in movies from 2002 or 2003? I think it's because CGI was such a costly, labor-intensive prospect back in those days that they took a lot more time to get it right, and it had to be used more sparingly. Anyway, I'm much likelier to be wowed by The Abyss than by just about anything to come out in summer 2010, I can assure you of that.

But yes, that tentacle: Lindsey has by now formed a theory that those lights in the abyss are proof of non-terrestrial intelligence, or NTIs, and the water psuedopod is almost certainly under their control. And this is where The Abyss starts to become very edit-dependent, and indeed where the film both starts to slide off the deep end and turn into something far more interesting than just another "action movie with grunts". I said that Cameron wanted to make his own 2001; but he really wanted to make his own Close Encounters of the Third Kind, if some of the particular images he copied from that film are any indication. The basic issue is that CET3K is a fantasy at heart, where The Abyss is an action movie; and the transition from Cameron's comfort zone to his more Spielbergian climax is not an altogether smooth one. There's a big problem in that The Abyss suffers from a whopper of a false ending: most of the drama of the film has been driven by the conflict between Bud and the increasingly unhinged Coffey, who elects to blow up the NTIs with one of the nukes he swiped from the submarine. Eventually this spills out into a fairly awesome undersea chase in two submersibles, and eventually - SPOILER WARNING FOR THE NEXT SENTENCE AND THE NEXT PARAGRAPH, SINCE I KNOW THAT MORE PEOPLE HAVEN'T SEEN THE ABYSS THAN OTHER JAMES CAMERON MOVIES! - Coffey's vessel crashes and falls into the abyss. About two-thirds of the way through the movie.

Frankly, I don't think this issue could have been solved: the climax doesn't work if Coffey is alive, but the movie has weird structural issues with him dead for the last third. 'Tis an intractable thing, and a pity. In any case, the fourth act begins with Bud preparing to descend into the abyss to disarm the nuke, with about one hour until it blows; this involves him filling up with a breathable oxygen-rich liquid that we earlier saw demonstrated on a rat, winning the approbation of the ASPCA - but damn, is it a cool substance and a cool concept, even if they just faked it with Ed Harris. Down he goes, into the depths of his own sanity, anchored by the voice of his wife (for naturally, they have fallen back in love as a result of these adventures), and he disarms the warhead; but he hasn't enough oxygen to get back up, so he settles down to die. And that is when the NTIs find him, and the two versions of The Abyss take their final, absolute departure from each other. At all points, the extended cut has been better: but only now does the theatrical cut cease to be much of a movie at all. In the earlier version, Bud meets the aliens, they flash some text of his conversation with Lindsey in what looks like an attempt to communicate, and then they save everybody - and it makes no damn sense. The theatrical Abyss basically has no point, except, There are aliens. But they are not rolled into the drama whatsoever, and frankly, I'm not that surprised that the response to the film in 1989 was muted: it turns out to be two hours and 20 minutes in service of a whiz-bang deus ex machina. The extended cut is absolutely different: after saving Bud, the aliens trigger a series of tidal waves that will decimate the human population; but this turns out to be nothing else than a warning, that we should stop our nasty, Cold Warring ways, for the aliens looked into Bud's heart and saw goodness, and have decided to give humanity another chance. Absolutely, this is not a new idea, but at least it means that The Abyss means something, that in fact all of the drama, based in man's pettiness and fear, had a direction it was heading all along (it also pays off the hints that the Russians are flipping out over the sunken sub, a thread that just sort of trails off pointlessly in the theatrical cut).

Neither Abyss is absolutely flawless, granted: even in the extended cut, subplots end up lost in the ether, and that false finale really makes you feel the running time in a way that the propulsive narrative of Aliens didn't, although that film is nearly as long as the theatrical cut of The Abyss. Still, Cameron had such a keen eye for how to stage action in a way that was both "omigod so cool" thrilling, and yet entirely attentive to the language of cinema. This was the first of the director's films in an anamorphic widescreen ratio, and he proved to have a fairly good idea of what to do with that frame; no outright masterpiece of composition in the way of Kurosawa Akira's widescreen movies were, nor even Spielberg's, but there is a satisfying lack of dead space except where it is clearly a well-chosen visual element. And of course, Cameron's love of underwater tech, seen here for the first but certainly not the last time, results in some of the most bravura scenes and shots ever attempted in the notoriously difficult conditions of an underwater shoot.

In essence, you can tell that The Abyss was a labor of love, emphasis on "labor"; and if it is not the absolutely top of its director's craft, it's still a darn sight better than most of what passes for popcorn entertainment, now or then. Despite everything, it still crackles along and, especially in the extended cut, it showcases Cameron's peculiar skill at turning stock characters and trite dialogue into the stuff of legitimately smart and emotionally engaging pop entertainment.

At the time, Cameron's film was one of the poor bastards that had to give way to the onslaught of the likes of Batman and Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade, and depending on whose budget estimate you listen to ($70 million is usually considered authoritative), the film only barely eked out a profit on international sales - given advertising, it seems likely to assume that it lost money. Time has been fairly kind to it, owing no doubt to fanboyism and the director's rather good-sized following, but one not be a Cameron acolyte to recognise that The Abyss has aged better than some of the films that outshone it back in the day - quick, who wants to take in a double feature of Parenthood and Turner & Hooch? - even as we must all probably concede that it isn't nearly the achievement of its two predecessors, nor his next project, an ill-advised Terminator sequel that ended up being one of the best American action movies of the 1990s. But I'm not here to bury The Abyss, but to praise it as a fairly brainier sci-fi action flick than we're typically used to.

Ah, but which Abyss do I mean? For in the case of this particular film, the "extended cut" issue raises its thorny head in a far more difficult case than we had with Aliens, or with the great majority of special edition edits. In Aliens, as you recall, most of the scenes added had an invisible quality, adding bits of character detail without affecting the plot. There are really only two points of particular significance: the addition of Ripley's dead grown-up daughter, giving a boost to her relationship with the orphan girl Newt; and the poor decision (in my opinion) to add a scene on the space colony before its fall. But these really only augment the Aliens that already exists. This is, of course, the nature of most such cuts: the same movie has a bit more info and hopefully a bit more impact, but it is the same movie.

Not so with The Abyss. 20th Century Fox Home Video has very carefully never called their 1993 version of the film a "Director's Cut", and I do not know James Cameron's particular opinion on the matter; I do know that he had final cut on the movie as long as it was within a certain running time, so perhaps he left certain particular moments on the cutting room floor to ensure that he'd get the rest of the movie exactly how he wanted it. I also know that the 1993 version of The Abyss, running 28 minutes longer (and three minutes of extra end credits) than the 140 minute theatrical cut, is in essence not the same movie as the theatrical cut. I don't mean that in some high-falutin' "to change even one frame is to change the movie entire" film theory way. I mean, literally, that the 171 minute Abyss tells a materially different story than the 140 minute Abyss, and for my tastes, it tells a much, much better story at that; it's one of those rare cases where adding footage makes the thing feel shorter, for all the new footage clicks so well and adds a richness that the original lacked.

In either case, The Abyss tells of the crew of an Deep Core 2, an experimental deep-sea oil platform in the Bahamas, who are contracted by the U.S. Navy to aid in the salvage of a nuclear submarine that went down under mysterious circumstances - the audience knows more than the government, in that we saw the strange blue and pink light that caused the ship to lose its power, but at this point we're even pretty well left in the dark. The leader of the drillers is Bud Brigman (Ed Harris), a rock-solid blue collar type, who isn't terribly keen to have a mirthless SEAL by the name of Coffey (Michael Biehn, in his last film with Cameron) ordering him around, but he likes his job too much to complain. In this he is quite altogether less passionate than his estranged wife Lindsey (Mary Elizabeth Mastrantonio), the designer of the deep-sea rig, who has quite the possessive, protective view of her baby, and doesn't care to see a bunch of rough military types banging it about.

Once the SEALS get down to Deep Core, the story - either variant of it - proceeds in a vaguely plotless direction, watching as the men (and two women) go about their chores in fairly close, even documentary-esque detail, allowing for the fact that The Abyss presents a completely fictional situation, so the word "documentary" is horribly inapt. Bud and Coffey butt heads over leadership, the crew operates machines and goes diving in the wreck of the sub, and strange events keep happening: first, inside the downed vessel, one of the drillers, Jammer (John Bedford Lloyd) sees something pink and blue that startles him so much that he hyperventilates himself into a coma; later, Lindsey twice spots some kind of inexplicable objects that look a bit like translucent plastic sea beasts, but glow and cause power failures in nearby electronic objects. As all this is happening, a major crisis looms: due to the hurricane up top, the rig has been dragged to the very edge of an unfathomably deep abyss, and in the process was damaged enough that it's taken on water, and both the heating and oxygen systems have taken a hit - if the crew can't figure out how to fix things, they'll be freezing in four hours, and suffocating in well under a day. Not to mention that Coffey is starting to suffer from psychosis, brought on by pressurization sickness; and damn it all, but he's the one in charge of the guns.

The difference between the two cuts throughout this passage (the first 100 minutes of the theatrical cut, the first two hours of the extended version) is largely one of tone: in both cases, there's a certain stretched-out observational feel that suggests, especially considering what happens later, that Cameron was trying to make his very own 2001: A Space Odyssey (that Stanley Kubrick film was also visually referenced several times in Aliens), following with a certain detachment as people try to go about their very high-tech business as Something Paranormal is flitting about just where you can't see it, but the extended cut benefits from stretching out the stretching-out with a bevy of added character details. In the original version, the crew of the rig has the bland uniformity of any blue-collar team of heroes, all identified by nicknames like Catfish (Leo Burmester) and One Night (Kimberly Scott) and Hippy (Todd Graff), and defined by one personality trait and their job; they are not even as distinct as the Central Casting marines in Aliens. But the little extensions of scenes add a good deal of depth and personality to virtually every one of the characters, and give us a far better sense of Bud and Lindsey's broken marriage, and what that break has cost each of them. There's also one big scene added entirely new, one that adds quite a bit to the character of the drillers: as One Night pilots the Flatbed (basically, the tow-ship used to move the rig about), she listens to Linda Ronstadt's trucker anthem "Willing", and as a couple other characters hear it on the intercom, they start to sing along. It's a sweet little moment that shows the extended family tightness of the crew, and allows us to see what exactly Cameron - a former truck driver, we must not forget - was aiming at in his depiction of these rough workers.

Not that the theatrical cut is without its nuanced little moments: one of the best parts of either cut is the detail of Bud's wedding ring, which he throws in a chemical toilet after fighting with Lindsey (though the extended cut explains this fight better); when he fishes it out a moment later, it stains his hand blue, and that stain is present for the rest of the film, a vivid but never overbearing detail that constantly reminds us of his personal stakes throughout the piece. It is a bit disingenuous to speak of any James Cameron film in terms of the richness of its characterisations, but at the same time he doesn't scrimp in that area like a lot of similar filmmakers: consider Michael Bay's Armageddon, with its army of writers, that also takes a look at a team of oil drillers but can't be arsed to come up with even a fraction of the sympathetic representation that Cameron whipped up all on his own.

Along the way, we get treated to a lot of really nifty setpieces, evidence of the director's intense love of well-crafted spectacle: the absurd amount of underwater photography and scenes in flooded interiors (largely without stunt doubles!) may have made the film a living hell to shoot for everyone concerned - Mastrantonio supposedly suffered a nervous breakdown in the middle of shooting, which probably led to her vocal objections to the amount of good footage snipped out of the theatrical cut - but it resulted in a rather enjoyable summer movie, full of chaotic, exciting incident that never reaches down to the condescending depths of so very many of the films in that mold that have seen release in the last 20 years. The Abyss might have had an absurd price tag in terms in both financial and human terms, but you cannot say that we don't see that $70 million on the screen, in all of the fantastic underwater footage, great models, and most notably, a really stunning and groundbreaking use of CGI courtesy of Industrial Light and Magic, bringing to life a semi-sentient tentacle of water snaking through Deep Core - it was, after Willow, only the second use of CGI morphing in cinema history, and what was insanely cool in 1989 still holds up exceedingly well today - am I alone in noticing that computer-generated effects in the early years, such as here, or in Terminator 2 or Jurassic Park, look infinitely more convincing than the effects in movies from 2002 or 2003? I think it's because CGI was such a costly, labor-intensive prospect back in those days that they took a lot more time to get it right, and it had to be used more sparingly. Anyway, I'm much likelier to be wowed by The Abyss than by just about anything to come out in summer 2010, I can assure you of that.

But yes, that tentacle: Lindsey has by now formed a theory that those lights in the abyss are proof of non-terrestrial intelligence, or NTIs, and the water psuedopod is almost certainly under their control. And this is where The Abyss starts to become very edit-dependent, and indeed where the film both starts to slide off the deep end and turn into something far more interesting than just another "action movie with grunts". I said that Cameron wanted to make his own 2001; but he really wanted to make his own Close Encounters of the Third Kind, if some of the particular images he copied from that film are any indication. The basic issue is that CET3K is a fantasy at heart, where The Abyss is an action movie; and the transition from Cameron's comfort zone to his more Spielbergian climax is not an altogether smooth one. There's a big problem in that The Abyss suffers from a whopper of a false ending: most of the drama of the film has been driven by the conflict between Bud and the increasingly unhinged Coffey, who elects to blow up the NTIs with one of the nukes he swiped from the submarine. Eventually this spills out into a fairly awesome undersea chase in two submersibles, and eventually - SPOILER WARNING FOR THE NEXT SENTENCE AND THE NEXT PARAGRAPH, SINCE I KNOW THAT MORE PEOPLE HAVEN'T SEEN THE ABYSS THAN OTHER JAMES CAMERON MOVIES! - Coffey's vessel crashes and falls into the abyss. About two-thirds of the way through the movie.

Frankly, I don't think this issue could have been solved: the climax doesn't work if Coffey is alive, but the movie has weird structural issues with him dead for the last third. 'Tis an intractable thing, and a pity. In any case, the fourth act begins with Bud preparing to descend into the abyss to disarm the nuke, with about one hour until it blows; this involves him filling up with a breathable oxygen-rich liquid that we earlier saw demonstrated on a rat, winning the approbation of the ASPCA - but damn, is it a cool substance and a cool concept, even if they just faked it with Ed Harris. Down he goes, into the depths of his own sanity, anchored by the voice of his wife (for naturally, they have fallen back in love as a result of these adventures), and he disarms the warhead; but he hasn't enough oxygen to get back up, so he settles down to die. And that is when the NTIs find him, and the two versions of The Abyss take their final, absolute departure from each other. At all points, the extended cut has been better: but only now does the theatrical cut cease to be much of a movie at all. In the earlier version, Bud meets the aliens, they flash some text of his conversation with Lindsey in what looks like an attempt to communicate, and then they save everybody - and it makes no damn sense. The theatrical Abyss basically has no point, except, There are aliens. But they are not rolled into the drama whatsoever, and frankly, I'm not that surprised that the response to the film in 1989 was muted: it turns out to be two hours and 20 minutes in service of a whiz-bang deus ex machina. The extended cut is absolutely different: after saving Bud, the aliens trigger a series of tidal waves that will decimate the human population; but this turns out to be nothing else than a warning, that we should stop our nasty, Cold Warring ways, for the aliens looked into Bud's heart and saw goodness, and have decided to give humanity another chance. Absolutely, this is not a new idea, but at least it means that The Abyss means something, that in fact all of the drama, based in man's pettiness and fear, had a direction it was heading all along (it also pays off the hints that the Russians are flipping out over the sunken sub, a thread that just sort of trails off pointlessly in the theatrical cut).

Neither Abyss is absolutely flawless, granted: even in the extended cut, subplots end up lost in the ether, and that false finale really makes you feel the running time in a way that the propulsive narrative of Aliens didn't, although that film is nearly as long as the theatrical cut of The Abyss. Still, Cameron had such a keen eye for how to stage action in a way that was both "omigod so cool" thrilling, and yet entirely attentive to the language of cinema. This was the first of the director's films in an anamorphic widescreen ratio, and he proved to have a fairly good idea of what to do with that frame; no outright masterpiece of composition in the way of Kurosawa Akira's widescreen movies were, nor even Spielberg's, but there is a satisfying lack of dead space except where it is clearly a well-chosen visual element. And of course, Cameron's love of underwater tech, seen here for the first but certainly not the last time, results in some of the most bravura scenes and shots ever attempted in the notoriously difficult conditions of an underwater shoot.

In essence, you can tell that The Abyss was a labor of love, emphasis on "labor"; and if it is not the absolutely top of its director's craft, it's still a darn sight better than most of what passes for popcorn entertainment, now or then. Despite everything, it still crackles along and, especially in the extended cut, it showcases Cameron's peculiar skill at turning stock characters and trite dialogue into the stuff of legitimately smart and emotionally engaging pop entertainment.

Categories: action, james cameron, popcorn movies, science fiction, summer movies