Universal Horror: The spy who came in from the cold cream

There is a place that Universal could have sent its library of iconic monsters to in the 1940s that's so unbelievably obvious and offers so many opportunities for wonderful weirdness that, in retrospect, it's astonishing that it only happened once: the European theater of World War II. Imagine a 20th Century wolf man retaining just enough of his human morality to mostly contain his feral rampages to columns of Nazi soldiers; or the Afrikakorps running afoul of Kharis the mummy during its failed invasion of Egypt in 1942. Given Hitler's noted fascination with the occult, surely he'd have cause to try and revive the Frankenstein monster and Dracula, who were already right there in countries under German control.

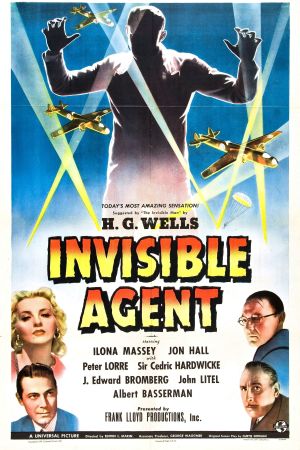

But alas, all these what-ifs are mere fantasies. Universal only went to the "monster goes to war" well just once, and it was with the character who was the hardest sell as a "monster" in the first place, in a movie that makes absolutely no feints towards horror. I refer to the 1942 summer release Invisible Agent, a spy thriller that very vaguely positions itself in continuity with the original The Invisible Man of '33, positing that the grandson of the mad scientist Dr. Griffin is alive and well in Manhattan, and still has the secret family recipe in his possession. Living under the alias "Frank Raymond", this Frank Griffin (Jon Hall) wants to live in peace and forget all about his granddad's flirtation with things outside of man's proper domain, but events in the autumn of 1941 make that impossible. First, a quartet of German agents led by SS-Gruppenführer Conrad Stauffer (Cedric Hardwicke) comes a-knocking, hoping to recruit Griffin as a Nazi agent and scientist. And I should point out sooner than the film did that one of those Germans, played by Peter Lorre, is in fact the Japanese Baron Ikito, and he is seen to be constantly jostling for position against Stauffer, apparently as eager to fuck over Germany as the United States. But none of this shows up in the first scene, and if you did not know beforehand that the curious make-up Lorre is wearing was meant to be yellowface, I truly do not imagine that you would ever guess. And certainly, Lorre's refusal to adjust his normal accent even slightly doesn't sell "Japanese" in any way.

So this visit is enough to trigger a second one, with the U.S. government formally informing Griffin that they've always known who he is, and have been content to let him live in quiet solitude, but now that it's already past that, how would he feel about letting Uncle Sam have the invisibility formula, huh? Griffin refuses, but we're only days away from 7 December at this point, and like many another patriotic American, the bombing of Pearl Harbor catapults him into action. He'll let the government have his formula to put an agent in Germany to make contact with one of their spies on one condition: that agent has to be Griffin himself. With great reluctance, the feds agree, and in no time at all, Griffin is riding a spectacularly awful-looking model plane (a conspicuously bad effect in a movie driven by its effects work) over Germany, parachuting out and stripping down to the amazement of the watching soldiers who are baffled when the canvass touches ground with no human being attached to it.

From here, Griffin (with no way to reverse his condition) meets up with coffin-maker and spy Arnold Schmidt (Albert Bassermann), who tells him of a list containing the names of every German and Japanese agent operating in the United States. With the help of the beautifully untrustworthy Maria Sorenson (Ilona Massey), a German operative with an unclear level of sympathy for America, Griffin is on the hunt, using his invisibilty to prank SS-Standartenführer Karl Heiser (J. Edward Bromberg), madly in love with Sorenson, and constantly looking for an angle against his boss, none other than our old buddy Stauffer. Who is still fending off the machinations of Ikito and his henchmen.

I quote that at some length - and I've gotten us only barely to the midpoint of an 81-minute film, more than indulgent for a Universal monster movie at this era (but then, the high cost of the Invisible Man spin-offs due to their effects kept them from making the same swerve into B-picturedom as, say, the increasingly junky mummy films) - to make the broad point that Invisible Agent is besotted with plot machinations. As is appropriate for a spy film, one might argue, and I'm sympathetic to it, but in this particular case, the development are less about the pile-up of shadowy cloak-and-dagger shenanigans than just throwing every idea that fit the concept at the wall and seeing what stuck. Screenwriter Curt Siodmak (his third Invisible picture, with his name here Americanised up to "Curtis") was a refugee from Nazi Germany, and Invisible Agent has the unmissable air of a "fuck you" gesture, not to its benefits as a narrative. Large parts of the film lose interest entirely on Griffin and Sorenson, instead focusing on Heiser's paranoid jockeying for power and Stauffer's flat, bureaucratic evilness, and Ikito's slithery Asiatic duplicity. The overriding sense is that these people are just so shitty, and should be mocked as clowns but also scorned and feared for their cruelty, and if we have to put the movie on pause to make that happen, well dammit, they're fucking Nazis. It's worth taking the time to show them what for.

Good red meat for a wartime audience, bad for cinematic elegance. The movie that results is sloppy as hell, and totally out of balance: melodrama specialist Edward L. Marin's direction shows no evidence of control or pacing, particular in one deadly scene where he lets Griffin's pranks during a dinner between Heiser and Sorenson go on for endless minutes - enough time for us to notice what a terrible, terrible spy Griffin is, sacrificing a tactical advantage like that, and what a frankly spoiled jealous brat he is about a woman he's just met and who has at least a 50% chance of being a Nazi triple agent. In fact, if there's one overriding problem with Invisible Agent, it's that Marin has no idea whether Siodmak has written a snarky anti-Nazi comedy or a tense anti-Nazi thriller, and so directs it as neither. This leads to unfunny comic scenes and slack spying scenes, and many scenes that amble without much urgency.

As a second-order problem, Hall and Massey make for a rather dreary pair of lead. The former has nothing better to bring to the table than a breezy flyboy cockiness that's not a good fit for the character of a reclusive scientist forced into spying. Massey, for her part, is just bad: lost in a thick Hungarian accent and apparently disinterested in answering for herself the questions of Sorenson's interior motives, responding to Hall's Griffin as an annoyed mom with an unruly toddler, a fascinating subversion of the "erotic tension between spies" trope that would be effective only if the rest of the film was in any way willing to go along with her.

So much for the A-plot. The oddest thing about Invisible Agent is that the scenes of Nazi politics, exactly the material that ruins the pacing all to hell, are also the only place where the film comes to life. That is in no small part because Lorre and Hardwicke are light-years beyond the rest of the cast (though Hardwicke is not, himself, so great that he threatens to redeem the whole movie): when Lorre ironically describes the Rose Bowl as "an incident of great national importance" in the first scene, the film promises a succulent vein of sardonic villainy which it does, in fairness, indulge in, every time Lorre shows up again. He just doesn't do it very much. Maybe that's a good thing: maybe Lorre's utterly beguiling self-amused wickedness is only so potent because the film parcels it out jealously. Whatever the case, it's one of his very best performances, spectacularly unpersuasive yellowface not withstanding, and it's the best argument for ever watching Invisible Agent. Even Marin's drippy directing jolts awake to take advantage of Lorre: the scene in which Ikito and Stauffer finally get their just rewards is staged with a level of visual drama totally absent from the rest of the movie, including a bravura tilt from a wide shot to a close-up that shows the men's corpses with shocking, noir-like callousness. Just watch that scene and you might think Invisible Agent was one of the all-time masterpieces of WWII cinema.

All of which is dancing around the real central question: how are the visual effects? Three films running, the Invisible Man pictures were first and above all exercises in increasingly jaw-dropping invisibility sequences, and Invisible Agent is the most ambitious yet: we see Griffin soaping up his legs in a bathtub, he drinks coffee (sadly, the film drops continuity in not showing the beverage pooling in his invisible stomach, he walks around with his face half-covered in cold cream, a way of making himself visible and therefore sexy for the benefit of Sorenson that doubles as a cost-cutting measure: cheaper to slather Hall's face in cold cream than staging a whole bunch of jackets with no heads. But it also adds a nice note of unexpected creepiness to the banal lovemaking scenes.

Ambition aside, the effects aren't great - it's a step down from The Invisible Woman, I am deeply sorry to say. The scale of the activities performed by Hall on set in a body stocking, interacting with props and actors constantly, is fearless and forward-looking, but it's imperfect: one can always see the ghostly outline of Hall's body in interior scenes. Always. This issue isn't "new" - John P. Fulton used the same basic idea to make people invisible in all of the movies, and you can spot the same artifacts in The Invisible Woman, at least - but it's much, much worse here than in any of its predecessors, owing perhaps to the film's generally brighter lighting. At any rate, the trade-off of having the boldest effects in the series is that the most exciting moments are also the least-convincing. Coupled with the blobby storytelling and generally slack directing, Invisible Agent is a disappointing step down: the first movie in a surprisingly reliable franchise that really can't offer much of anything to later generations other than the inherent fascination of wartime propaganda through the filter of genre filmmaking.

Reviews in this series

The Invisible Man (Whale, 1933)

The Invisible Man Returns (May, 1940)

The Invisible Woman (Sutherland, 1940)

Invisible Agent (Marin, 1942)

The Invisible Man's Revenge (Beebe, 1944)

Abbott and Costello Meet the Invisible Man (Lamont, 1951)

But alas, all these what-ifs are mere fantasies. Universal only went to the "monster goes to war" well just once, and it was with the character who was the hardest sell as a "monster" in the first place, in a movie that makes absolutely no feints towards horror. I refer to the 1942 summer release Invisible Agent, a spy thriller that very vaguely positions itself in continuity with the original The Invisible Man of '33, positing that the grandson of the mad scientist Dr. Griffin is alive and well in Manhattan, and still has the secret family recipe in his possession. Living under the alias "Frank Raymond", this Frank Griffin (Jon Hall) wants to live in peace and forget all about his granddad's flirtation with things outside of man's proper domain, but events in the autumn of 1941 make that impossible. First, a quartet of German agents led by SS-Gruppenführer Conrad Stauffer (Cedric Hardwicke) comes a-knocking, hoping to recruit Griffin as a Nazi agent and scientist. And I should point out sooner than the film did that one of those Germans, played by Peter Lorre, is in fact the Japanese Baron Ikito, and he is seen to be constantly jostling for position against Stauffer, apparently as eager to fuck over Germany as the United States. But none of this shows up in the first scene, and if you did not know beforehand that the curious make-up Lorre is wearing was meant to be yellowface, I truly do not imagine that you would ever guess. And certainly, Lorre's refusal to adjust his normal accent even slightly doesn't sell "Japanese" in any way.

So this visit is enough to trigger a second one, with the U.S. government formally informing Griffin that they've always known who he is, and have been content to let him live in quiet solitude, but now that it's already past that, how would he feel about letting Uncle Sam have the invisibility formula, huh? Griffin refuses, but we're only days away from 7 December at this point, and like many another patriotic American, the bombing of Pearl Harbor catapults him into action. He'll let the government have his formula to put an agent in Germany to make contact with one of their spies on one condition: that agent has to be Griffin himself. With great reluctance, the feds agree, and in no time at all, Griffin is riding a spectacularly awful-looking model plane (a conspicuously bad effect in a movie driven by its effects work) over Germany, parachuting out and stripping down to the amazement of the watching soldiers who are baffled when the canvass touches ground with no human being attached to it.

From here, Griffin (with no way to reverse his condition) meets up with coffin-maker and spy Arnold Schmidt (Albert Bassermann), who tells him of a list containing the names of every German and Japanese agent operating in the United States. With the help of the beautifully untrustworthy Maria Sorenson (Ilona Massey), a German operative with an unclear level of sympathy for America, Griffin is on the hunt, using his invisibilty to prank SS-Standartenführer Karl Heiser (J. Edward Bromberg), madly in love with Sorenson, and constantly looking for an angle against his boss, none other than our old buddy Stauffer. Who is still fending off the machinations of Ikito and his henchmen.

I quote that at some length - and I've gotten us only barely to the midpoint of an 81-minute film, more than indulgent for a Universal monster movie at this era (but then, the high cost of the Invisible Man spin-offs due to their effects kept them from making the same swerve into B-picturedom as, say, the increasingly junky mummy films) - to make the broad point that Invisible Agent is besotted with plot machinations. As is appropriate for a spy film, one might argue, and I'm sympathetic to it, but in this particular case, the development are less about the pile-up of shadowy cloak-and-dagger shenanigans than just throwing every idea that fit the concept at the wall and seeing what stuck. Screenwriter Curt Siodmak (his third Invisible picture, with his name here Americanised up to "Curtis") was a refugee from Nazi Germany, and Invisible Agent has the unmissable air of a "fuck you" gesture, not to its benefits as a narrative. Large parts of the film lose interest entirely on Griffin and Sorenson, instead focusing on Heiser's paranoid jockeying for power and Stauffer's flat, bureaucratic evilness, and Ikito's slithery Asiatic duplicity. The overriding sense is that these people are just so shitty, and should be mocked as clowns but also scorned and feared for their cruelty, and if we have to put the movie on pause to make that happen, well dammit, they're fucking Nazis. It's worth taking the time to show them what for.

Good red meat for a wartime audience, bad for cinematic elegance. The movie that results is sloppy as hell, and totally out of balance: melodrama specialist Edward L. Marin's direction shows no evidence of control or pacing, particular in one deadly scene where he lets Griffin's pranks during a dinner between Heiser and Sorenson go on for endless minutes - enough time for us to notice what a terrible, terrible spy Griffin is, sacrificing a tactical advantage like that, and what a frankly spoiled jealous brat he is about a woman he's just met and who has at least a 50% chance of being a Nazi triple agent. In fact, if there's one overriding problem with Invisible Agent, it's that Marin has no idea whether Siodmak has written a snarky anti-Nazi comedy or a tense anti-Nazi thriller, and so directs it as neither. This leads to unfunny comic scenes and slack spying scenes, and many scenes that amble without much urgency.

As a second-order problem, Hall and Massey make for a rather dreary pair of lead. The former has nothing better to bring to the table than a breezy flyboy cockiness that's not a good fit for the character of a reclusive scientist forced into spying. Massey, for her part, is just bad: lost in a thick Hungarian accent and apparently disinterested in answering for herself the questions of Sorenson's interior motives, responding to Hall's Griffin as an annoyed mom with an unruly toddler, a fascinating subversion of the "erotic tension between spies" trope that would be effective only if the rest of the film was in any way willing to go along with her.

So much for the A-plot. The oddest thing about Invisible Agent is that the scenes of Nazi politics, exactly the material that ruins the pacing all to hell, are also the only place where the film comes to life. That is in no small part because Lorre and Hardwicke are light-years beyond the rest of the cast (though Hardwicke is not, himself, so great that he threatens to redeem the whole movie): when Lorre ironically describes the Rose Bowl as "an incident of great national importance" in the first scene, the film promises a succulent vein of sardonic villainy which it does, in fairness, indulge in, every time Lorre shows up again. He just doesn't do it very much. Maybe that's a good thing: maybe Lorre's utterly beguiling self-amused wickedness is only so potent because the film parcels it out jealously. Whatever the case, it's one of his very best performances, spectacularly unpersuasive yellowface not withstanding, and it's the best argument for ever watching Invisible Agent. Even Marin's drippy directing jolts awake to take advantage of Lorre: the scene in which Ikito and Stauffer finally get their just rewards is staged with a level of visual drama totally absent from the rest of the movie, including a bravura tilt from a wide shot to a close-up that shows the men's corpses with shocking, noir-like callousness. Just watch that scene and you might think Invisible Agent was one of the all-time masterpieces of WWII cinema.

All of which is dancing around the real central question: how are the visual effects? Three films running, the Invisible Man pictures were first and above all exercises in increasingly jaw-dropping invisibility sequences, and Invisible Agent is the most ambitious yet: we see Griffin soaping up his legs in a bathtub, he drinks coffee (sadly, the film drops continuity in not showing the beverage pooling in his invisible stomach, he walks around with his face half-covered in cold cream, a way of making himself visible and therefore sexy for the benefit of Sorenson that doubles as a cost-cutting measure: cheaper to slather Hall's face in cold cream than staging a whole bunch of jackets with no heads. But it also adds a nice note of unexpected creepiness to the banal lovemaking scenes.

Ambition aside, the effects aren't great - it's a step down from The Invisible Woman, I am deeply sorry to say. The scale of the activities performed by Hall on set in a body stocking, interacting with props and actors constantly, is fearless and forward-looking, but it's imperfect: one can always see the ghostly outline of Hall's body in interior scenes. Always. This issue isn't "new" - John P. Fulton used the same basic idea to make people invisible in all of the movies, and you can spot the same artifacts in The Invisible Woman, at least - but it's much, much worse here than in any of its predecessors, owing perhaps to the film's generally brighter lighting. At any rate, the trade-off of having the boldest effects in the series is that the most exciting moments are also the least-convincing. Coupled with the blobby storytelling and generally slack directing, Invisible Agent is a disappointing step down: the first movie in a surprisingly reliable franchise that really can't offer much of anything to later generations other than the inherent fascination of wartime propaganda through the filter of genre filmmaking.

Reviews in this series

The Invisible Man (Whale, 1933)

The Invisible Man Returns (May, 1940)

The Invisible Woman (Sutherland, 1940)

Invisible Agent (Marin, 1942)

The Invisible Man's Revenge (Beebe, 1944)

Abbott and Costello Meet the Invisible Man (Lamont, 1951)