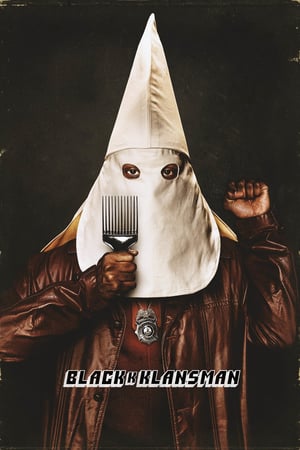

Klan you dig it?

The claims that BlacKkKlansman represents a renaissance for Spike Lee are at least slightly overheated. After all, even his very great movies are frustrating and flawed (except for Do the Right Thing, which is frustrating and perfect), and even his very bad movies are still interesting for the complexity and intensity of their ideas. There is, I mean to say, no such thing as a Spike Lee joint that isn't at least worth grappling with, in my experience (and admittedly, there are a substantial number of Lee films I haven't seen; I suppose it's likely that at least his remake of Oldboy from 2013 is not actually worth grappling with). That being said, it's been ages since any of Lee's fiction features have been so clear-headed and driven by a clear need to make bold, epochal declarations about The State Of American Culture - at least since 2002's 25th Hour, and I am more than comfortable making the claim that BlacKkKlansman is better than 25th Hour.

The film is based, with considerable embellishment and invention by its four credited writers (Charlie Wachtel & David Rabinowitz and Lee & Kevin Willmott), on the memoirs of Ron Stallworth, who in 1972 became the first African-American police officer in the city Colorado Springs. It wasn't until 1979 that the major events of the film took place (though the film is deliberately unclear about dates, suggesting that everything from Stallworth's hiring on takes place in the span of maybe several months), when Stallworth responded to classified ad welcoming the people of Colorado Springs to join a new chapter of the Ku Klux Klan, that most notorious of all U.S. hate groups. Stallworth, and the unnamed white narcotics officer who "played" him in the flesh, were able to tease out the identities of several KKK members in sensitive military positions, while Stallworth had numerous conversations with KKK national leader David Duke over the phone, and all of this remained a secret until after the detective's 2005 retirement.

BlacKkKlansman goes quite a bit far afield than that (though it's single most ludicrous moment, in which Stallworth ends up serving as Duke's police bodyguard while the officer pretending to be Stallworth was meeting the Klansman, is factual), and I wonder if it might have been better for it to have gone further still. Already, the film has come under some friendly fire for its upbeat portrayal of the police, and its ambivalent, half-formed attempt to raise questions about whether a black man can rightfully serve in a systemically racist career like a U.S. policeman, and this all ultimately comes about from the real Stallworth's apparently quite untroubled enjoyment of his job for another full quarter of a century after these events. But let us avoid rabbit holes, and simply appreciate the film as it sits in front of us, and oh! how much there is to appreciate. This is covering a whole lot of ground, tonally and thematically: it's at times hilarious, at times gutting, and it switches between the two modes more or less at will. Its general arc, though, is from comedy (sometimes very broad, even silly comedy) to a bleak pessimism about where American society is, where it's been, and where it's going, and this large-scale shift works as a kind of trap for the film's audience: first we're enticed by the movie, and we are blindsided by its anger and made to confront how not very funny at all things like the Ku Klux Klan actually are.

As with much politically activist art, it's not at all clear to me that BlacKkKlansman is in any danger of encountering audiences who don't already agree with its conclusions. It's also not guilty of hiding its message: the film is full of Klan members repeating, at times directly, the rhetoric of the Donald Trump presidential campaign and the contemporary right wing, and has a few sick jokes of the "thank God people like that will never hold political power" variety. And then, in case there is any remote doubt at all what the film is doing, it ends with footage of the 2017 Charlottesville, Virginia protests that resulted in the death of anti-racism activist Heather Heyer, and positions her and her fellow protesters as the direct heir to the heroes of the movie, just as surely as the Unite the Right marchers are linked with the Klan members. I frankly don't care for this rhetorical move on any level: it underlines in think lines what was already hardly obscure, and feels mildly exploitative on top of it (I find it to be little more than the leftist analogue to the terrible stock footage coda of American Sniper, and that's no good thing to be reminded of). Still, it's reflective of the extreme passion of the entire movie, and that, at least, is a necessary and great thing.

Simply put, BlacKkKlansman is what happens when a great filmmaker gets obviously, palpably inspired for the first time in ages, and so dumps absolutely everything he can into a project. This is a moviemaker's movie, with Lee demonstrating in several great scenes his sense of film history, particularly as it connects to race: the film's very first gesture is to present a clip from Gone with the Wind, and not just any old clip, but the clip - the long tracking shot that crosses over the huge field of the dead and dying and ends on the tattered Confederate flag. I'm sure that I read this moment differently than Lee does (I think it's one of the handful of more or less directly anti-Confederate moments in that entire feature, in part because of its melancholic soundtrack that has been noticeably redone in BlacKkKlansman to sound more triumphant), but he positions it well as an emblem of the way that American pop culture has romanticised the Confederacy, that greatest bastion of white supremacy, as beautifully tragic. And then the film shifts directly into a scene with Alec Baldwin hilariously cameoing as a certain Dr. Kennebrew Beauregard, sternly explaining the scientific basis for white superiority as his pale face is washed over in illegible images from some racist newsreel. Frequently, Beauregard gets tongue-tied and needs to ask for lines, downshifting from the raging vocal delivery of a true believer to the flat tones of a confused actor: it's funny as hell, and it's also a sharp reminder of the way that white supremacy is itself constructed, a rhetorical weapon as much as it is anything else.

BlacKkKlansman is, then, an attempt to stage a counter-rhetoric. I suspect the film's jagged shifts in tone is part of that; I am absolutely certain that part of it is also the alarming editing, courtesy of Lee's frequent cutter Barry Alexander Brown. The film is sloppy, loose, flagrantly disinterested in some of the most basic rules of spatial continuity, and it's definitely not by accident. The film wants to break the rules, and it wants to be caught doing it: it is a huge "fuck you" to the kind of nice bourgeois biopic that this sounds like it might have been, and thereby to the ideology responsible for nice bourgeois movies. The film's two best scenes are both about the meaning of images: in one, Black Panther legend Kwame Ture (Corey Hawkins), né Stokely Carmichael, stands before a crowd of students, calmly but firmly declaring the value of black beauty, and the film shows them watching in faultlessly-composed, gorgeously-lit portrait shots, faces against empty black backgrounds, gazing just to the side of the camera, vividly demonstrating the meaning of his words in the moment they're spoken. In the other, a rowdy Klan viewing of the infamous 1915 The Birth of a Nation is cross-cut with a meeting as a group of activists listen, rapt, as an old man played by Harry Belafonte quietly tells them the stories of the outrages he has scene. The irony isn't stressed, and it doesn't have to be: the Klansmen are the ones bellowing and hooting like rabid animals, exactly like the gruesome depiction of ex-slaves in the very movie they're watching, in tremendous contrast to the quiet fury with which the black audience absorbs the atrocities spoken in Belafonte's deeply soothing voice. It is a pointed attack that only a film historian would have thought of: using cross-cutting, the very reason that The Birth of a Nation remains "important", to rip apart that film's ugly imagery and viciously racist depictions. To use the film's legacy in order to destroy its legacy.

There is, of course, a narrative inside all of this; it's just that, like almost every Spike Lee film I've seen, the moments matter more than the whole. Still, it's a solid cop picture, as Stallworth (played by John David Washington, son of Lee's frequent collaborator Denzel Washington - they don't look much alike, but they sound eerily similar, and it's all the more noticeable since the film keeps demanding that we think about Stallworth's pinched, nasal intonation as he's mimicking a racist white person on the phone) teams up with the Jewish-and-quiet-about-it Flip Zimmerman (Adam Driver) to conduct one of the most reckless undercover operations imaginable. The film is great at constructing scenes of tension, various moments at which it seems like Flip's flimsy disguise will be blown; Lee and his team do excellent work in keeping Washington and Driver blocked away within the frame to feel constantly besieged by the people around them (openly racist cops, suspicious Klansmen). It's also simply great at populating the world with supporting characters who feel big and cartoonish, but not so cartoonish that they cease to register as people, the way they might if this were the Coen film it occasional resembles. The Klan members are ludicrious gargoyles, but they're ludicrous gargoyles who feel like you might bump into them walking down the street - a fine line to walk, and BlacKkKlansman does it all throughout its running time.

The one thing the film isn't great at is its biggest invented subplot (or second-biggest: Zimmerman is a composite figure, and his film-long attempt to grapple with what it means to be Jewish amongst white supremacists is a major strand of the film that the screenwriters invented; it is also not a strand that really has much of a conclusion): Stallworth's flirtation with a student activist, Patrice (Laura Harrier), that he's also been assigned to spy on, at least in the early going. It's the problem I've already touched on: as much as the film wants to be about Stallworth's inner conflict between being a good cop and being a black man, real history won't permit that theme to be developed well enough to do anything with it. And the Patrice subplot is basically only about that part of the movie; that, and giving her all of the lines of dialogue that cue the viewer what Big Questions to think about, in a highly leading way. It's annoying, and a little clumsy, though Harrier is terrific; still, if BlacKkKlansman weren't so anxious to make sure we understand the issues it's talking about, to see what the problems are, and to question our assumptions, I have to assume that all of the wonderful things about it would be compromised, perhaps fatally. So a little bit of hand-holding is warranted, I suppose. After all, this is first and foremost an urgent film, and urgency is never a rhetorically subtle thing. Besides, the film's point is that there's nothing subtle at all about the world we live in, a world in which literal Nazis are getting respectable airtime on cable news channels, and one should absolutely not pussyfoot around in trying to combat that. That seems worth of some righteous passion, even if it manifests in a certain artlessness at the edges.

The film is based, with considerable embellishment and invention by its four credited writers (Charlie Wachtel & David Rabinowitz and Lee & Kevin Willmott), on the memoirs of Ron Stallworth, who in 1972 became the first African-American police officer in the city Colorado Springs. It wasn't until 1979 that the major events of the film took place (though the film is deliberately unclear about dates, suggesting that everything from Stallworth's hiring on takes place in the span of maybe several months), when Stallworth responded to classified ad welcoming the people of Colorado Springs to join a new chapter of the Ku Klux Klan, that most notorious of all U.S. hate groups. Stallworth, and the unnamed white narcotics officer who "played" him in the flesh, were able to tease out the identities of several KKK members in sensitive military positions, while Stallworth had numerous conversations with KKK national leader David Duke over the phone, and all of this remained a secret until after the detective's 2005 retirement.

BlacKkKlansman goes quite a bit far afield than that (though it's single most ludicrous moment, in which Stallworth ends up serving as Duke's police bodyguard while the officer pretending to be Stallworth was meeting the Klansman, is factual), and I wonder if it might have been better for it to have gone further still. Already, the film has come under some friendly fire for its upbeat portrayal of the police, and its ambivalent, half-formed attempt to raise questions about whether a black man can rightfully serve in a systemically racist career like a U.S. policeman, and this all ultimately comes about from the real Stallworth's apparently quite untroubled enjoyment of his job for another full quarter of a century after these events. But let us avoid rabbit holes, and simply appreciate the film as it sits in front of us, and oh! how much there is to appreciate. This is covering a whole lot of ground, tonally and thematically: it's at times hilarious, at times gutting, and it switches between the two modes more or less at will. Its general arc, though, is from comedy (sometimes very broad, even silly comedy) to a bleak pessimism about where American society is, where it's been, and where it's going, and this large-scale shift works as a kind of trap for the film's audience: first we're enticed by the movie, and we are blindsided by its anger and made to confront how not very funny at all things like the Ku Klux Klan actually are.

As with much politically activist art, it's not at all clear to me that BlacKkKlansman is in any danger of encountering audiences who don't already agree with its conclusions. It's also not guilty of hiding its message: the film is full of Klan members repeating, at times directly, the rhetoric of the Donald Trump presidential campaign and the contemporary right wing, and has a few sick jokes of the "thank God people like that will never hold political power" variety. And then, in case there is any remote doubt at all what the film is doing, it ends with footage of the 2017 Charlottesville, Virginia protests that resulted in the death of anti-racism activist Heather Heyer, and positions her and her fellow protesters as the direct heir to the heroes of the movie, just as surely as the Unite the Right marchers are linked with the Klan members. I frankly don't care for this rhetorical move on any level: it underlines in think lines what was already hardly obscure, and feels mildly exploitative on top of it (I find it to be little more than the leftist analogue to the terrible stock footage coda of American Sniper, and that's no good thing to be reminded of). Still, it's reflective of the extreme passion of the entire movie, and that, at least, is a necessary and great thing.

Simply put, BlacKkKlansman is what happens when a great filmmaker gets obviously, palpably inspired for the first time in ages, and so dumps absolutely everything he can into a project. This is a moviemaker's movie, with Lee demonstrating in several great scenes his sense of film history, particularly as it connects to race: the film's very first gesture is to present a clip from Gone with the Wind, and not just any old clip, but the clip - the long tracking shot that crosses over the huge field of the dead and dying and ends on the tattered Confederate flag. I'm sure that I read this moment differently than Lee does (I think it's one of the handful of more or less directly anti-Confederate moments in that entire feature, in part because of its melancholic soundtrack that has been noticeably redone in BlacKkKlansman to sound more triumphant), but he positions it well as an emblem of the way that American pop culture has romanticised the Confederacy, that greatest bastion of white supremacy, as beautifully tragic. And then the film shifts directly into a scene with Alec Baldwin hilariously cameoing as a certain Dr. Kennebrew Beauregard, sternly explaining the scientific basis for white superiority as his pale face is washed over in illegible images from some racist newsreel. Frequently, Beauregard gets tongue-tied and needs to ask for lines, downshifting from the raging vocal delivery of a true believer to the flat tones of a confused actor: it's funny as hell, and it's also a sharp reminder of the way that white supremacy is itself constructed, a rhetorical weapon as much as it is anything else.

BlacKkKlansman is, then, an attempt to stage a counter-rhetoric. I suspect the film's jagged shifts in tone is part of that; I am absolutely certain that part of it is also the alarming editing, courtesy of Lee's frequent cutter Barry Alexander Brown. The film is sloppy, loose, flagrantly disinterested in some of the most basic rules of spatial continuity, and it's definitely not by accident. The film wants to break the rules, and it wants to be caught doing it: it is a huge "fuck you" to the kind of nice bourgeois biopic that this sounds like it might have been, and thereby to the ideology responsible for nice bourgeois movies. The film's two best scenes are both about the meaning of images: in one, Black Panther legend Kwame Ture (Corey Hawkins), né Stokely Carmichael, stands before a crowd of students, calmly but firmly declaring the value of black beauty, and the film shows them watching in faultlessly-composed, gorgeously-lit portrait shots, faces against empty black backgrounds, gazing just to the side of the camera, vividly demonstrating the meaning of his words in the moment they're spoken. In the other, a rowdy Klan viewing of the infamous 1915 The Birth of a Nation is cross-cut with a meeting as a group of activists listen, rapt, as an old man played by Harry Belafonte quietly tells them the stories of the outrages he has scene. The irony isn't stressed, and it doesn't have to be: the Klansmen are the ones bellowing and hooting like rabid animals, exactly like the gruesome depiction of ex-slaves in the very movie they're watching, in tremendous contrast to the quiet fury with which the black audience absorbs the atrocities spoken in Belafonte's deeply soothing voice. It is a pointed attack that only a film historian would have thought of: using cross-cutting, the very reason that The Birth of a Nation remains "important", to rip apart that film's ugly imagery and viciously racist depictions. To use the film's legacy in order to destroy its legacy.

There is, of course, a narrative inside all of this; it's just that, like almost every Spike Lee film I've seen, the moments matter more than the whole. Still, it's a solid cop picture, as Stallworth (played by John David Washington, son of Lee's frequent collaborator Denzel Washington - they don't look much alike, but they sound eerily similar, and it's all the more noticeable since the film keeps demanding that we think about Stallworth's pinched, nasal intonation as he's mimicking a racist white person on the phone) teams up with the Jewish-and-quiet-about-it Flip Zimmerman (Adam Driver) to conduct one of the most reckless undercover operations imaginable. The film is great at constructing scenes of tension, various moments at which it seems like Flip's flimsy disguise will be blown; Lee and his team do excellent work in keeping Washington and Driver blocked away within the frame to feel constantly besieged by the people around them (openly racist cops, suspicious Klansmen). It's also simply great at populating the world with supporting characters who feel big and cartoonish, but not so cartoonish that they cease to register as people, the way they might if this were the Coen film it occasional resembles. The Klan members are ludicrious gargoyles, but they're ludicrous gargoyles who feel like you might bump into them walking down the street - a fine line to walk, and BlacKkKlansman does it all throughout its running time.

The one thing the film isn't great at is its biggest invented subplot (or second-biggest: Zimmerman is a composite figure, and his film-long attempt to grapple with what it means to be Jewish amongst white supremacists is a major strand of the film that the screenwriters invented; it is also not a strand that really has much of a conclusion): Stallworth's flirtation with a student activist, Patrice (Laura Harrier), that he's also been assigned to spy on, at least in the early going. It's the problem I've already touched on: as much as the film wants to be about Stallworth's inner conflict between being a good cop and being a black man, real history won't permit that theme to be developed well enough to do anything with it. And the Patrice subplot is basically only about that part of the movie; that, and giving her all of the lines of dialogue that cue the viewer what Big Questions to think about, in a highly leading way. It's annoying, and a little clumsy, though Harrier is terrific; still, if BlacKkKlansman weren't so anxious to make sure we understand the issues it's talking about, to see what the problems are, and to question our assumptions, I have to assume that all of the wonderful things about it would be compromised, perhaps fatally. So a little bit of hand-holding is warranted, I suppose. After all, this is first and foremost an urgent film, and urgency is never a rhetorically subtle thing. Besides, the film's point is that there's nothing subtle at all about the world we live in, a world in which literal Nazis are getting respectable airtime on cable news channels, and one should absolutely not pussyfoot around in trying to combat that. That seems worth of some righteous passion, even if it manifests in a certain artlessness at the edges.