It matters if you're black or white

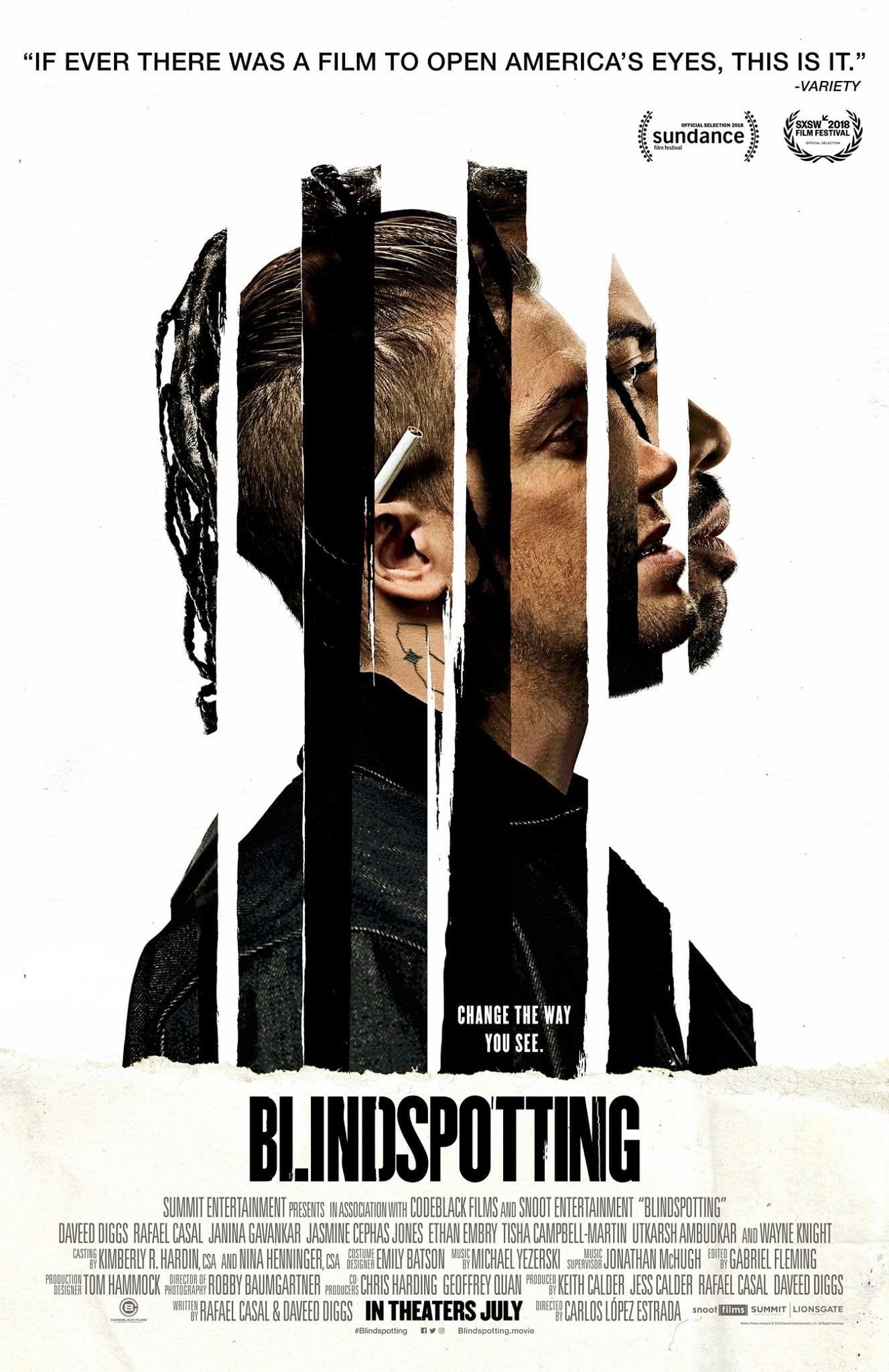

There are, I would imagine, very few similarities between Marfa, Texas (2010 population: 1981) and Oakland, California (2010 population: 390,724). But they share this one thing: they both somehow became holy sites for filmmaking for very brief periods of time. In August 2006, Marfa was the base of operations for two different film shoots, those of No Country for Old Men and There Will Be Blood, which went on to be two of the defining films (maybe even the two defining films) of the 2007 movie year. In June 2017, Oakland hosted the production of two films that have since followed each other closely, premiering two days apart at the 2018 Sundance Film Festival and receiving their U.S. commercial releases three weeks apart in July 2018: Sorry to Bother You and Blindspotting, the latter of which is our current subject. Obviously I'm not fool enough to suggest what we'll view as the defining films of 2018 a decade from now, but I certainly wouldn't be surprised if those two made the list, and I'd be even less upset by it. They're two great movies, among the most thematically interesting social message films of the 2010s and both spiked by enough aesthetic creativity to remain interesting as cinema qua cinema.

I will be bold enough to predict that Blindspotting is going to spend the rest of its life in the shadow of Sorry to Bother You, and that's a huge shame. The two films are approaching broadly the same topic (systemic racism in contemporary America), but from two very different angles and with two very different specific messages. Blindspotting, for its part, is first and foremost a buddy comedy, which is already a pretty enjoyable surprise: if I told you the plot and the central conflict and all that, I guess you'd assume (as I very much did) that it would be a generally sober, somber treatment of The Problems Today in which we all very very much concerned and upset. On the contrary! Blindspotting is hardly a fluffy farce, but it is routinely more funny than not, and at times very funny, in its laconic "what can ya do?" treatment of its plot.

The buddies are Collin and Miles, played by real-life buddies Daveed Diggs and Rafael Casal, who are also the film's screenwriters: apparently they've had a version of the screenplay for years, hoping to bring their affectionate portrayal of the ugliness but also the human beauty of Oakland to the screen but never being able to quite get it put together (one imagines that Diggs's time in Hamilton, for which he won a Tony, helped finally grease some wheels). There is one thing we notice about them immediately: Collin is black and Miles is white, but Miles acts much more consistently in line with what most of us would consider stereotypically "black behavior". Also, Collin is an ex-convict, and we'll learn around midway through that Miles almost without question should have been convicted right alongside him, but has instead been contentedly living in domestic bliss with his African-American girlfriend Ashley (Jasmine Cephas Jones) and watching as she does pretty much all the work raising their son Sean (Ziggy Baitinger). The film almost entirely takes place during the last three days of Collin's probation, as he tries to keep his head down and just grind through while working with Miles at a moving company. Unfortunately, this is right about the time that Miles decides to illegally buy a handgun, which he waves around like a baton twirler at every moment.

That's already plenty to fuel a movie, and it's literally only about half of what Blindspotting is up to. The other half is to portray Oakland with the fine attention to detail that only a native could possibly come up with, and white a complicated portrayal it is: the film captures a city in the early throes of gentrification, with local greasy spoon take-out places suddenly switching to vegan menus, the corner convenience store offering $10/bottle fresh-pressed vegetable juice on its cluttered, scuffed counters, and the grim spectre of white guys in fashionably trashy clothes using slang words that middle class white guys had oughtn't use. There's more ambivalence here than it might sound: while Miles is horrified on a spiritual level to see the city that he identifies with at a bone-deep level changing into something increasingly generic and commercialised, Collin seems willing to roll with it, or at least to view it with good humor rather than outraged terror. And this city-in-flux proves to be a perfect backdrop for the story of a friendship in crisis, with Collin forced to confront the fact that Miles is never, ever going to own up to the fact that being white means he can get away with a lot more stupid shit.

Despite this, there's no sense in which Blindspotting is, conventionally speaking, a "message movie". I cannot imagine how somebody might fail to notice the film's various observations (it really doesn't make "arguments"), but it never leads with them; it's a character piece first and foremost, primarily interested in how Collin copes with the whirlwind of things happening in these last 72 hours of probation: Miles and the gun, for sure, but also the killing of a fleeing man by a cop that happens mere yards away while Collin is stopped at a red light. It's also a remarkably good portrayal of a friendship that, despite its increasingly obvious conflicts, just plain works: Diggs and Casal, who are both individually wonderful in their performances, have incredible onscreen chemistry together, and there's a very real magnetism between them that makes it clear why Collin still wants Miles in his life even when Miles has become an outright liability. This is, indeed, part of why Blindspotting is so unexpectedly easy to watch: we're getting intimate, first-hand exposure to the easygoing relationship between two men who know how to make each other happy.

That's a big part of how Blindspotting survives what should be its fatal flaw: this movie is all over the place tonally. Sometimes its has the warm stickiness of Miles and Sean goofing around; sometimes the chill tension of Collin, bathed in the harsh red of a stoplight, watching a killer cop staring at him; sometimes the goofy comedy of a pair of two bros riffing; sometimes the impeccable black comedy of a shaggy dog story told with goofy voices in which we watch our heroes brutally beating a man. It should feel like a catastrophe of moods flying in every direction, but the actors and first-time director Carlos López Estrada (a music video veteran), aided by the implacable fact of Oakland itself, keep the film bound together through some alchemy that I can't even start to explain. It absolutely shouldn't work, and it absolutely does, and that is that.

At any rate, the film is a joy to watch, even when it's punishingly clear-eyed about the hard limits of life for a poor African-American ex-con. López Estrada came armed with a whole lot of ideas about style, and the film is almost as much of an aesthetic grab-bag as it is tonally. Hell, just the way that he and cinematographer Robby Baumgartner (who has only served that role on a few movies, but has logged plenty of credits as a camera operator - including, I am delighted to find, There Will Be Blood) use lighting is enough to make a case: sometimes, the film is light with the vomitous yellow light of a city at night to serve a strict realism, sometimes the neon colors of stores or (as alluded to) the primary colors of stoplights are used in a way that is by definition "realistic", but with a rich, boldly Expressionist quality that feels hardly realistic at all. And sometimes it's neither of those, as for example the early depiction of a fast-food restaurant as a beacon of welcoming bright colors against an impossibly inky black background like it exists in a pure nihilistic void; it feels nothing at all like realism and instead like something out of folklore (and for Miles, it basically is).

There are plenty of other lovely stylistic touches, to be sure, both in the filming and in the writing. Sometimes, these overlap, as in a scene where Collin demonstrates his impromptu rhyming skills with occasional assists from Miles: it's a mildly ethereal moment, thanks to the dramatic shift in dialogue rhythm, and López Estrada boosts this by filming it as a fluid, gliding long take that floats backwards as the characters walk towards the camera.

It is, at any rate, an exciting debut from the writers and director alike, a strong showcase for Casal's ability to give an apparently one-note loudmouth shadings of self-doubt and desperation, and an entirely excellent showcase for Diggs to do most things, whether it's the small smiles he offers as he watches the world, the look of drained terror when he's letting us know that he's thinking about that shooting, the adolescent embarrassment of his incompetent attempts to flirt with his coworker and occasional girlfriend Val (Janina Gavankar), or his ability to wince and look worried in a seemingly unlimited variety of ways.

There are some first-timer's limitations: López Estrada isn't afraid of some cheesy sound cues and scene transitions - the latter stand out more since there also some extremely inspired transitions, one of which comes between the first two scenes in the movie - and the first half of the movie is particularly littered with moments where the film clearly demonstrates the difference between enthusiastic newbies doing things because they can, and moments where seasoned filmmakers do things because they have worked out a good reason for it. I'm also pretty dubious about the film's second climax. The first climax is a scorcher, a kind of naturalistic-operatic explosion of personal grievances that's impressively, if very loudly, acted by the principles. The second climax keeps the operatic scale but it's frankly contrived and implausible, and though I certainly get how it thinks it's paying off Collin's anguish about the violence done against black men, I'm not entirely sure that it does pay off. Or at any rate, it could have paid off with less screen time and without explaining the film's title so stiffly. Still, these are petty complaints. I frankly loved the film, and I look forward to seeing what these filmmakers do next, and even when it oversteps, the movie has a vitality that makes me feel pretty good that it's going to age well. It is excitingly watchable, brashly cinematic, full of ideas, and full of the idealism of the very best American indie cinema.

I will be bold enough to predict that Blindspotting is going to spend the rest of its life in the shadow of Sorry to Bother You, and that's a huge shame. The two films are approaching broadly the same topic (systemic racism in contemporary America), but from two very different angles and with two very different specific messages. Blindspotting, for its part, is first and foremost a buddy comedy, which is already a pretty enjoyable surprise: if I told you the plot and the central conflict and all that, I guess you'd assume (as I very much did) that it would be a generally sober, somber treatment of The Problems Today in which we all very very much concerned and upset. On the contrary! Blindspotting is hardly a fluffy farce, but it is routinely more funny than not, and at times very funny, in its laconic "what can ya do?" treatment of its plot.

The buddies are Collin and Miles, played by real-life buddies Daveed Diggs and Rafael Casal, who are also the film's screenwriters: apparently they've had a version of the screenplay for years, hoping to bring their affectionate portrayal of the ugliness but also the human beauty of Oakland to the screen but never being able to quite get it put together (one imagines that Diggs's time in Hamilton, for which he won a Tony, helped finally grease some wheels). There is one thing we notice about them immediately: Collin is black and Miles is white, but Miles acts much more consistently in line with what most of us would consider stereotypically "black behavior". Also, Collin is an ex-convict, and we'll learn around midway through that Miles almost without question should have been convicted right alongside him, but has instead been contentedly living in domestic bliss with his African-American girlfriend Ashley (Jasmine Cephas Jones) and watching as she does pretty much all the work raising their son Sean (Ziggy Baitinger). The film almost entirely takes place during the last three days of Collin's probation, as he tries to keep his head down and just grind through while working with Miles at a moving company. Unfortunately, this is right about the time that Miles decides to illegally buy a handgun, which he waves around like a baton twirler at every moment.

That's already plenty to fuel a movie, and it's literally only about half of what Blindspotting is up to. The other half is to portray Oakland with the fine attention to detail that only a native could possibly come up with, and white a complicated portrayal it is: the film captures a city in the early throes of gentrification, with local greasy spoon take-out places suddenly switching to vegan menus, the corner convenience store offering $10/bottle fresh-pressed vegetable juice on its cluttered, scuffed counters, and the grim spectre of white guys in fashionably trashy clothes using slang words that middle class white guys had oughtn't use. There's more ambivalence here than it might sound: while Miles is horrified on a spiritual level to see the city that he identifies with at a bone-deep level changing into something increasingly generic and commercialised, Collin seems willing to roll with it, or at least to view it with good humor rather than outraged terror. And this city-in-flux proves to be a perfect backdrop for the story of a friendship in crisis, with Collin forced to confront the fact that Miles is never, ever going to own up to the fact that being white means he can get away with a lot more stupid shit.

Despite this, there's no sense in which Blindspotting is, conventionally speaking, a "message movie". I cannot imagine how somebody might fail to notice the film's various observations (it really doesn't make "arguments"), but it never leads with them; it's a character piece first and foremost, primarily interested in how Collin copes with the whirlwind of things happening in these last 72 hours of probation: Miles and the gun, for sure, but also the killing of a fleeing man by a cop that happens mere yards away while Collin is stopped at a red light. It's also a remarkably good portrayal of a friendship that, despite its increasingly obvious conflicts, just plain works: Diggs and Casal, who are both individually wonderful in their performances, have incredible onscreen chemistry together, and there's a very real magnetism between them that makes it clear why Collin still wants Miles in his life even when Miles has become an outright liability. This is, indeed, part of why Blindspotting is so unexpectedly easy to watch: we're getting intimate, first-hand exposure to the easygoing relationship between two men who know how to make each other happy.

That's a big part of how Blindspotting survives what should be its fatal flaw: this movie is all over the place tonally. Sometimes its has the warm stickiness of Miles and Sean goofing around; sometimes the chill tension of Collin, bathed in the harsh red of a stoplight, watching a killer cop staring at him; sometimes the goofy comedy of a pair of two bros riffing; sometimes the impeccable black comedy of a shaggy dog story told with goofy voices in which we watch our heroes brutally beating a man. It should feel like a catastrophe of moods flying in every direction, but the actors and first-time director Carlos López Estrada (a music video veteran), aided by the implacable fact of Oakland itself, keep the film bound together through some alchemy that I can't even start to explain. It absolutely shouldn't work, and it absolutely does, and that is that.

At any rate, the film is a joy to watch, even when it's punishingly clear-eyed about the hard limits of life for a poor African-American ex-con. López Estrada came armed with a whole lot of ideas about style, and the film is almost as much of an aesthetic grab-bag as it is tonally. Hell, just the way that he and cinematographer Robby Baumgartner (who has only served that role on a few movies, but has logged plenty of credits as a camera operator - including, I am delighted to find, There Will Be Blood) use lighting is enough to make a case: sometimes, the film is light with the vomitous yellow light of a city at night to serve a strict realism, sometimes the neon colors of stores or (as alluded to) the primary colors of stoplights are used in a way that is by definition "realistic", but with a rich, boldly Expressionist quality that feels hardly realistic at all. And sometimes it's neither of those, as for example the early depiction of a fast-food restaurant as a beacon of welcoming bright colors against an impossibly inky black background like it exists in a pure nihilistic void; it feels nothing at all like realism and instead like something out of folklore (and for Miles, it basically is).

There are plenty of other lovely stylistic touches, to be sure, both in the filming and in the writing. Sometimes, these overlap, as in a scene where Collin demonstrates his impromptu rhyming skills with occasional assists from Miles: it's a mildly ethereal moment, thanks to the dramatic shift in dialogue rhythm, and López Estrada boosts this by filming it as a fluid, gliding long take that floats backwards as the characters walk towards the camera.

It is, at any rate, an exciting debut from the writers and director alike, a strong showcase for Casal's ability to give an apparently one-note loudmouth shadings of self-doubt and desperation, and an entirely excellent showcase for Diggs to do most things, whether it's the small smiles he offers as he watches the world, the look of drained terror when he's letting us know that he's thinking about that shooting, the adolescent embarrassment of his incompetent attempts to flirt with his coworker and occasional girlfriend Val (Janina Gavankar), or his ability to wince and look worried in a seemingly unlimited variety of ways.

There are some first-timer's limitations: López Estrada isn't afraid of some cheesy sound cues and scene transitions - the latter stand out more since there also some extremely inspired transitions, one of which comes between the first two scenes in the movie - and the first half of the movie is particularly littered with moments where the film clearly demonstrates the difference between enthusiastic newbies doing things because they can, and moments where seasoned filmmakers do things because they have worked out a good reason for it. I'm also pretty dubious about the film's second climax. The first climax is a scorcher, a kind of naturalistic-operatic explosion of personal grievances that's impressively, if very loudly, acted by the principles. The second climax keeps the operatic scale but it's frankly contrived and implausible, and though I certainly get how it thinks it's paying off Collin's anguish about the violence done against black men, I'm not entirely sure that it does pay off. Or at any rate, it could have paid off with less screen time and without explaining the film's title so stiffly. Still, these are petty complaints. I frankly loved the film, and I look forward to seeing what these filmmakers do next, and even when it oversteps, the movie has a vitality that makes me feel pretty good that it's going to age well. It is excitingly watchable, brashly cinematic, full of ideas, and full of the idealism of the very best American indie cinema.