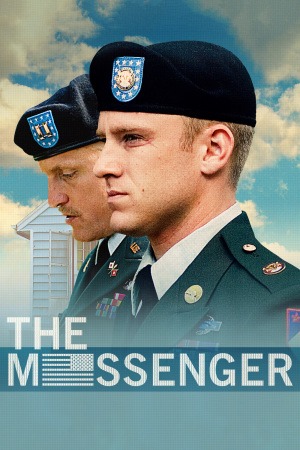

The bearers of bad news

Points for originality: the directorial debut of screenwriter Oren Moverman, The Messenger, adopts a perspective toward the Iraq War - to war in general - that I can't recall having seen before. It is the story of Will Montgomery (Ben Foster), an Army staff sergeant returned home thanks to some nasty physical damage, who is given an assignment to wrap up the last three months of his tour that he would absolutely prefer to avoid: he is given the task of visiting the homes of soldiers who died in country, and breaking the bad news to their next of kin.

It's the kind of story that makes one reflectively say to oneself, "I'd never really thought about that", right before one grimaces at using such a critic's cliché, but the hell of it is, I really never have thought about that before. Watch even a teeny-tiny number of war pictures, and you're going to get very used to that scene where a middle-aged lady in a sun-dappled kitchen hears a car door shut, and she goes to the front door and looks out to see two men in dress uniforms walking to the front door, and then she starts to hyperventilate, and when the taller and more authoritative man opens his mouth to say, "Ma'am", she breaks down completely, probably holding on to stair banister as she sinks to the ground. Even money says that the scene is all shot without sound, so the sensitive, mournful violin score can really hammer at the audience's heartstrings. So anyway, that's a boilerplate scene, right? But never have I ever seen a movie where the point of the scene is the man who has to break the news, till The Messenger. And as it turns out, that makes for a reasonably decent character study: a soldier who has faced death and witnessed men die feet away from him - late in the movie, Montgomery describes something absolutely hideous called "flesh shrapnel", and it's pretty much what you're thinking of - and who would still rather face all of those nightmares of the combat zone than have to stare a mother in the face and tell her that her son has died.

As far as Iraq War Message Pictures go, we can say this much about The Messenger: it's profoundly anxious to make sure you understand that people die in Iraq, a lot. Oh my, oh my, are you ever going to to not forget that fact during the one hour and 52 minutes of this film; the numerous scenes of Montgomery and his colleague/trainer Captain Tony Stone (Woody Harrelson) visiting families and sharing the awful news, each of them pitched in a different emotional and dramatic way, are presented with far too much soul-wracking, "watch as the actors cry lustfully" immensity. It's extremely crude storytelling - also crude is the manner in which each visit seems to fulfill some line on a checklist of dramatically varied forms of grief - but its crudity isn't really a detriment, and though I'm not tremendously proud of the fact, God knows I was moved and sometimes quite bothered by these sequences.

That said, The Messenger isn't an Iraq War Message Picture, at heart: it's a Post-War Character Study of Montgomery and Stone, two men whose combat experiences could hardly have been more different (Stone served in Desert Storm) each reliving their memories and dealing with their unresolved feelings about war and death as a result of what they see. The film takes a very writerly approach to all this, befitting the fact that the director is a trained screenwriter (he collaborated here with the largely untested Alessandro Camon): character is never spelled out except in brief flashes, but mostly expressed as an accumulation of details, some of them symbolic and some merely suggestive, and on the whole we in the audience are put in the role of the observer, rather than receiving the filmmaker's complete report on who these people are and why. It's a sometimes irritatingly opaque way to present a story, but in the main watching the two men is so very fascinating that it's easy to forgive. Both actors give outstanding performances - Foster has never been better - that imply without stating, allowing us to understand and interpret the men as we will, without having anything forced down our throats. A most uncommonly hands-off approach for character building in American cinema.

Yet, as writerly as I may find all of this, it's strange to note that the film is marred by a lumpy, ham-fisted screenplay: if not in matters of character, then certainly in dialogue (quite a collection of plonking, unreadable lines) and scenario. That the visits with the bereaved families seem a bit too functional, I already mentioned, but there's also the awkward and stiff veer from observational, episodic narrative to something plottier for about 25 minutes, right around the hour mark, when Montgomery takes a significantly too-personal interest in one of the widows he's given the news to, Olivia Pitterson (Samantha Morton). The whole thing feels uncomfortably melodramatic, and Olivia's size in the plot is out of proportion to the detail of character on the page; so let's be doubly thankful that Morton, one of the best actresses we've got right now, does such best-in-show work to make the character come together despite having little in the way of clear or even coherent motivations.

Oddly, Moverman makes for a better director than a writer, even as a first timer. There are some tentative zooms that I might have been happier without, but he and cinematographer Buddy Bukowski make unusually good use of the anamorphic widescreen frame, letting the unexpectedly large amounts of negative space in the film's compositions do so much of the heavy lifting for the story. The film's visuals are subtle, and quiet; nearly invisible, one might say. But they are also proof that the best kind of cinematic tricks are the ones that you barely think about, for I myself was quite taken by the film's emptiness and worn-out tone long before I thought to notice how much of that feeling was caused simply by the bleak compositions.

If The Messenger is not so good as 2009's other prominent Iraq drama, The Hurt Locker, this has much to do with its relative lack of urgency; it is essentially low-key and miserable, though not miserabilist. War and death are miserable things, after all. And, when all is said and done, The Messenger spends too much time working against its screenplay, which does err on the side of big emotions and stilted dialogue sometimes. But still, in a minor way, this is a moving depiction of something that we don't often think about, in art or in life: the endless hell of being one of the people whose job is to constantly talk about other people's deaths.

7/10

It's the kind of story that makes one reflectively say to oneself, "I'd never really thought about that", right before one grimaces at using such a critic's cliché, but the hell of it is, I really never have thought about that before. Watch even a teeny-tiny number of war pictures, and you're going to get very used to that scene where a middle-aged lady in a sun-dappled kitchen hears a car door shut, and she goes to the front door and looks out to see two men in dress uniforms walking to the front door, and then she starts to hyperventilate, and when the taller and more authoritative man opens his mouth to say, "Ma'am", she breaks down completely, probably holding on to stair banister as she sinks to the ground. Even money says that the scene is all shot without sound, so the sensitive, mournful violin score can really hammer at the audience's heartstrings. So anyway, that's a boilerplate scene, right? But never have I ever seen a movie where the point of the scene is the man who has to break the news, till The Messenger. And as it turns out, that makes for a reasonably decent character study: a soldier who has faced death and witnessed men die feet away from him - late in the movie, Montgomery describes something absolutely hideous called "flesh shrapnel", and it's pretty much what you're thinking of - and who would still rather face all of those nightmares of the combat zone than have to stare a mother in the face and tell her that her son has died.

As far as Iraq War Message Pictures go, we can say this much about The Messenger: it's profoundly anxious to make sure you understand that people die in Iraq, a lot. Oh my, oh my, are you ever going to to not forget that fact during the one hour and 52 minutes of this film; the numerous scenes of Montgomery and his colleague/trainer Captain Tony Stone (Woody Harrelson) visiting families and sharing the awful news, each of them pitched in a different emotional and dramatic way, are presented with far too much soul-wracking, "watch as the actors cry lustfully" immensity. It's extremely crude storytelling - also crude is the manner in which each visit seems to fulfill some line on a checklist of dramatically varied forms of grief - but its crudity isn't really a detriment, and though I'm not tremendously proud of the fact, God knows I was moved and sometimes quite bothered by these sequences.

That said, The Messenger isn't an Iraq War Message Picture, at heart: it's a Post-War Character Study of Montgomery and Stone, two men whose combat experiences could hardly have been more different (Stone served in Desert Storm) each reliving their memories and dealing with their unresolved feelings about war and death as a result of what they see. The film takes a very writerly approach to all this, befitting the fact that the director is a trained screenwriter (he collaborated here with the largely untested Alessandro Camon): character is never spelled out except in brief flashes, but mostly expressed as an accumulation of details, some of them symbolic and some merely suggestive, and on the whole we in the audience are put in the role of the observer, rather than receiving the filmmaker's complete report on who these people are and why. It's a sometimes irritatingly opaque way to present a story, but in the main watching the two men is so very fascinating that it's easy to forgive. Both actors give outstanding performances - Foster has never been better - that imply without stating, allowing us to understand and interpret the men as we will, without having anything forced down our throats. A most uncommonly hands-off approach for character building in American cinema.

Yet, as writerly as I may find all of this, it's strange to note that the film is marred by a lumpy, ham-fisted screenplay: if not in matters of character, then certainly in dialogue (quite a collection of plonking, unreadable lines) and scenario. That the visits with the bereaved families seem a bit too functional, I already mentioned, but there's also the awkward and stiff veer from observational, episodic narrative to something plottier for about 25 minutes, right around the hour mark, when Montgomery takes a significantly too-personal interest in one of the widows he's given the news to, Olivia Pitterson (Samantha Morton). The whole thing feels uncomfortably melodramatic, and Olivia's size in the plot is out of proportion to the detail of character on the page; so let's be doubly thankful that Morton, one of the best actresses we've got right now, does such best-in-show work to make the character come together despite having little in the way of clear or even coherent motivations.

Oddly, Moverman makes for a better director than a writer, even as a first timer. There are some tentative zooms that I might have been happier without, but he and cinematographer Buddy Bukowski make unusually good use of the anamorphic widescreen frame, letting the unexpectedly large amounts of negative space in the film's compositions do so much of the heavy lifting for the story. The film's visuals are subtle, and quiet; nearly invisible, one might say. But they are also proof that the best kind of cinematic tricks are the ones that you barely think about, for I myself was quite taken by the film's emptiness and worn-out tone long before I thought to notice how much of that feeling was caused simply by the bleak compositions.

If The Messenger is not so good as 2009's other prominent Iraq drama, The Hurt Locker, this has much to do with its relative lack of urgency; it is essentially low-key and miserable, though not miserabilist. War and death are miserable things, after all. And, when all is said and done, The Messenger spends too much time working against its screenplay, which does err on the side of big emotions and stilted dialogue sometimes. But still, in a minor way, this is a moving depiction of something that we don't often think about, in art or in life: the endless hell of being one of the people whose job is to constantly talk about other people's deaths.

7/10

Categories: indies and pseudo-indies, mr. cheney's war, oscarbait, very serious movies