Blockbuster History: The lawless borderlands

Every week this summer, we'll be taking an historical tour of the Hollywood blockbuster by examining an older film that is in some way a spiritual precursor to one of the weekend's wide releases. This week: Sicario: Day of the Soldado presents a uniquely ill-timed new take on the old trope of lawmen trying to tame the American Southwest. I would like to share with you now a less nihilistic variant on similar material.

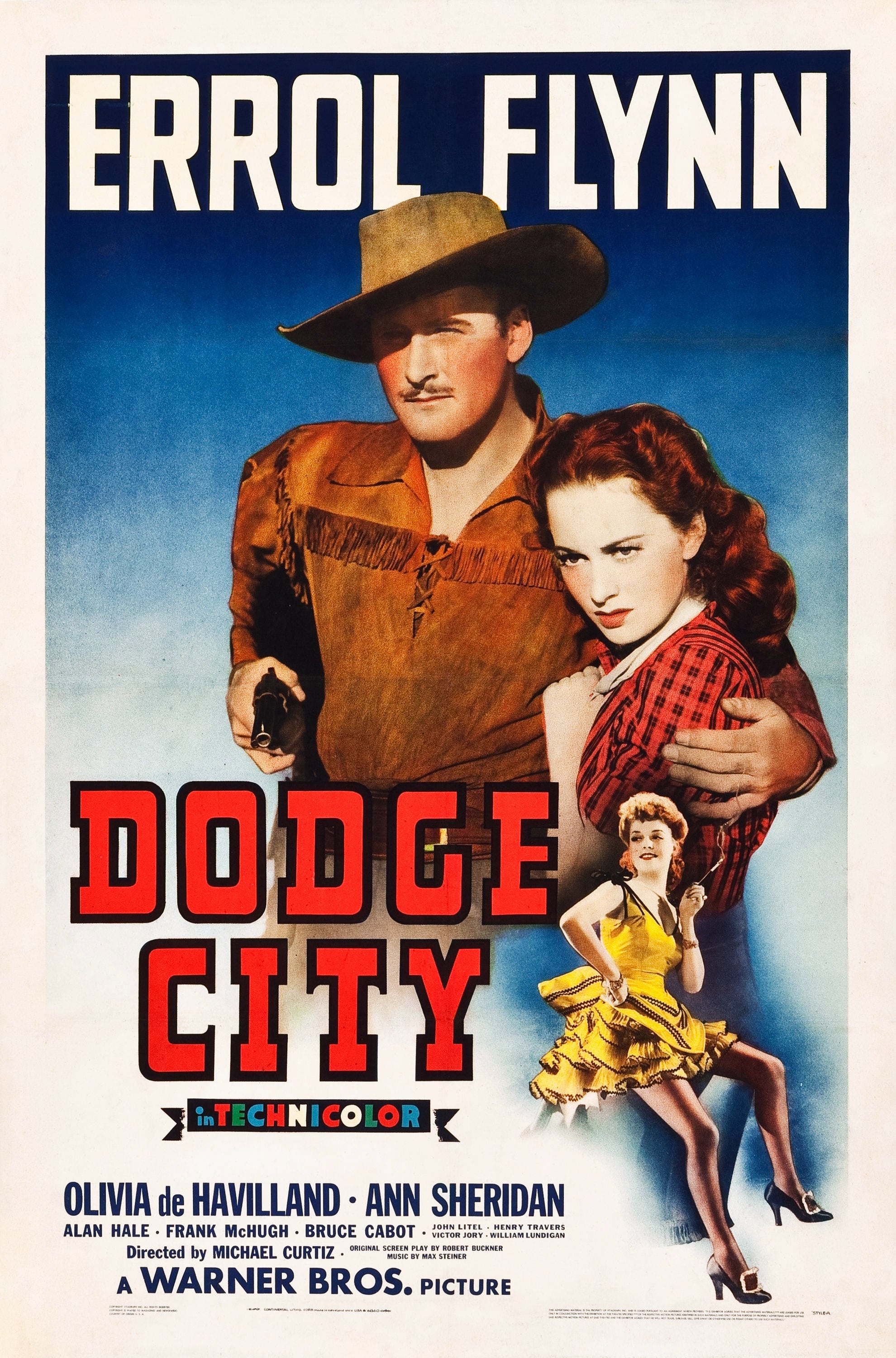

It's no exaggeration at all to declare 1939 the single most consequential year in the history of the Western movie.* After some very high-profile, prestigious, expensive hits in the mid-'20s, the genre had settled into ultra-cheap B-movie status, a natural effect of how effortless it was for producers looking to save a buck to shoot a Western in the scrubby wastelands within a short drive of Hollywood. It was only in 1939 that two very different films came along to rejuvenate the form with their artistry and even more their massive financial success, leading to the entire glorious history of Westerns and quasi-Westerns from the U.S., Italy, Australia, the Soviet Union, and goodness knows how many other places. One of those films, the John Ford-directed independent film Stagecoach, remains one of the canonical masterpieces of the genre. The other, opening just a few weeks later in the spring of '39, has certainly lost more of its luster over the intervening decades, though I think it's fair to say that purely in terms of narrative convention, the Warner Bros. A-picture Dodge City has the greater overall influence.

The film comes square in the middle of the acrimonious run of collaborations between star Errol Flynn and director Michael Curtiz: it is the sixth of their eleven projects together. And getting close to the point where those collaborations started to get sour: one year later, the duo would make Virginia City, a production self-evidently trying to re-do Dodge City, and the contrast between the 1939 original, which is mostly charming and surefooted, and its 1940 successor, which is clumsy and misguided, is maybe the best way to appreciate just how right Dodge City went.

That despite Flynn's own intense uncertainty and discomfort with the project. It has long been known that the Tasmanian-born actor considered his suave demeanor and England-facing Mid-Atlantic accent to be all wrong at playing a literal cowboy, and you can see it in his performance: whereas the Flynn of the previous year's stellar The Adventures of Robin Hood is pure bliss to watch, with his easygoing smirks and relaxedly athletic body language, the Flynn we see in Dodge City is a bit pent up and tight. When he walks, you can see just a little doubt in his eyes and his hips: am I supposed to swagger? Is this swaggering? I feel like I'm clomping. Still, those moments of visible doubt by no means overwhelm the character of Wade Hatton, who benefits from one of Flynn's most earnest performances, with more quite, introspective moral fiber - if Flynn supposed that the job of a Western star was to be taciturn and decent, he did a very good job of evoking those qualities.

The film itself, as scripted by Robert Buckner, is something of a sprawling epic history of the titular Kansas town, which was founded in 1872 as a watering hole for U.S. Army soldiers, in anticipation of the impending arrival of the Santa Fe Railroad. The film presents a swift, and of course substantially inaccurate history of all this, taking its time before even getting to Hatton's part of the plot. Indeed, the film might well be at its very best in its lingering prologue, which shows a train racing through the prairie, filling the frame with bright, sunshiny colors and the impression of terrific speed (the opening two shots, one a close-up of the front of the train and the next a wide shot that tracks along with it, both shake and wobble terribly; this should be bad, but it somehow manages to suggest the raw power and speed of the locomotive engine). As we'll find out soon enough, Dodge City is unusually invested in action sequences for a film of its era, and surprisingly good at it; the opening of the film, both in these shots and in the generally fast-paced, chattering history to follow, give us an immediate sense of momentum that will carry over the rest of the feature.

At any rate, this all happens in 1866, pointedly reminding us that the U.S. Civil War is still fresh in everybody's mind, and then we move ahead to '73, at which point Hatton is leading a team of cattle from Texas to Dodge City, which has firmly ensconced itself as the most important nexus for the cattle industry west of Chicago. And here the actual plot starts to assert itself, though it rarely does it directly: the short version is that Dodge City is an anarchic pit where good men get out as fast as possible and bad men indulge themselves in petty tyranny. The worst of these bad men is Jeff Surrett (Bruce Cabot), who immediately ends up taking a disliking to Hatton when the cowman refuses to accept his offer at auction, knowing a villain when he sees one. It's in part that interpersonal dynamic - but much more a sense of morality when faced with the utter lawlessness of Dodge City, in which not even the smallest child is safe - that leads Hatton to accept the job of sheriff. This makes him just one of several forces working to civilise the place: an ineffective temperance movement, the Pure Prairie League, shows the way, but there's also the newspaper run by Joe Clemens (Frank McHugh), and the symbolic presence of one Abbie Irving (Olivia de Havilland), a hard-working woman of both physical and emotional endurance who stands midway between the prim Pure Prairie Leaguers and the worldly dance hall singer Ruby Gilman (Ann Sheridan).

In short, Dodge City is in part the story of a good man reluctantly standing up against the bad man, bringing the taming influence of The Law where it had previously found no root, and in this respect is like many Westerns before it and even more Westerns after it. But it is also a somewhat abstract story about Dodge City itself, and frontier-era Kansas, and basically the whole matter of the West: the film is far more interested in the social currents under the town than in the mind and body of Wade Hatton. Which may very well be simply a matter of Michael Curtiz being more interested in crowds than in Flynn and de Havilland (the latter of whom was getting fed up with playing beatific ingenues, and lobbied to get Sheridan's role instead; her avowed boredom manifests in her performance every bit as much as Flynn's self-consciousness). It's a very strange, one might even honestly say malformed story: there are numerous digressions and no singular, clear narrative line until the second half. The most apparent of these digressions is a saloon sequence that, I guess, could be defended by showing Surrett's general nastiness: it's a scene that finds Ruby leading a rousing performance of "Marching Through Georgia", to the happy enthusiasm of most of the saloon patrons, until Surrett and his fellow ex-Southerners interrupt with a counter-performance of "Dixie", leading to a barfight that spills out into the street. Hatton never shows up in this sequence, and Surrett's explicit Southernness doesn't matter anywhere else in the film; so why include such a long detour? Simply because, in this moment, what the film finds interesting is the awareness that the Wild West was a melting pot for ex-Union and ex-Confederate forces, and much of the society of the West was the clash between two identities that, officially, no longer existed (though they have proxies: Kansan vs. Texan, townfolk vs. cowboy, Eastern law vs. Western anarchy). The scene itself feels like a clear first attempt at the magnificent "La Marseillaise" scene from Curtiz's later Casablanca; the scenes function differently, and the Dodge City scene is more clumsily executed (primarily in the sound mixing), but the sense of pregnant tension between two irreconcilable, but cohabiting societies is identical.

This is all very much percolating under the surface: for the most part, Dodge City is content to operate at the solitary level of being a fast-paced action movie, in which Flynn trades in swashbuckling for gunslinging to good effect. It's a big splashy Hollywood spectacle, with gorgeous sets and a riot of colors in the costumes and wide-open skies (which range from ludicrously glowing blues to warm sunsets in every hue of red and orange), not a social document, and certainly not a reliable history lesson. But it is, at least, a Hollywood spectacle that takes place at a clearly defined moment in time, dredging up real and important fissures in American society to fuel its conflict, and that background gives it more bite than just any old Western romp. On top of the overall excellence of its production, it's little wonder this film did so much to rejuvenate and legitimise its fading genre.

*As an accident of history, it pleases me that American cinema's greatest single year would be definitive for the most quintessentially American movie genre (give or take the gangster picture).

It's no exaggeration at all to declare 1939 the single most consequential year in the history of the Western movie.* After some very high-profile, prestigious, expensive hits in the mid-'20s, the genre had settled into ultra-cheap B-movie status, a natural effect of how effortless it was for producers looking to save a buck to shoot a Western in the scrubby wastelands within a short drive of Hollywood. It was only in 1939 that two very different films came along to rejuvenate the form with their artistry and even more their massive financial success, leading to the entire glorious history of Westerns and quasi-Westerns from the U.S., Italy, Australia, the Soviet Union, and goodness knows how many other places. One of those films, the John Ford-directed independent film Stagecoach, remains one of the canonical masterpieces of the genre. The other, opening just a few weeks later in the spring of '39, has certainly lost more of its luster over the intervening decades, though I think it's fair to say that purely in terms of narrative convention, the Warner Bros. A-picture Dodge City has the greater overall influence.

The film comes square in the middle of the acrimonious run of collaborations between star Errol Flynn and director Michael Curtiz: it is the sixth of their eleven projects together. And getting close to the point where those collaborations started to get sour: one year later, the duo would make Virginia City, a production self-evidently trying to re-do Dodge City, and the contrast between the 1939 original, which is mostly charming and surefooted, and its 1940 successor, which is clumsy and misguided, is maybe the best way to appreciate just how right Dodge City went.

That despite Flynn's own intense uncertainty and discomfort with the project. It has long been known that the Tasmanian-born actor considered his suave demeanor and England-facing Mid-Atlantic accent to be all wrong at playing a literal cowboy, and you can see it in his performance: whereas the Flynn of the previous year's stellar The Adventures of Robin Hood is pure bliss to watch, with his easygoing smirks and relaxedly athletic body language, the Flynn we see in Dodge City is a bit pent up and tight. When he walks, you can see just a little doubt in his eyes and his hips: am I supposed to swagger? Is this swaggering? I feel like I'm clomping. Still, those moments of visible doubt by no means overwhelm the character of Wade Hatton, who benefits from one of Flynn's most earnest performances, with more quite, introspective moral fiber - if Flynn supposed that the job of a Western star was to be taciturn and decent, he did a very good job of evoking those qualities.

The film itself, as scripted by Robert Buckner, is something of a sprawling epic history of the titular Kansas town, which was founded in 1872 as a watering hole for U.S. Army soldiers, in anticipation of the impending arrival of the Santa Fe Railroad. The film presents a swift, and of course substantially inaccurate history of all this, taking its time before even getting to Hatton's part of the plot. Indeed, the film might well be at its very best in its lingering prologue, which shows a train racing through the prairie, filling the frame with bright, sunshiny colors and the impression of terrific speed (the opening two shots, one a close-up of the front of the train and the next a wide shot that tracks along with it, both shake and wobble terribly; this should be bad, but it somehow manages to suggest the raw power and speed of the locomotive engine). As we'll find out soon enough, Dodge City is unusually invested in action sequences for a film of its era, and surprisingly good at it; the opening of the film, both in these shots and in the generally fast-paced, chattering history to follow, give us an immediate sense of momentum that will carry over the rest of the feature.

At any rate, this all happens in 1866, pointedly reminding us that the U.S. Civil War is still fresh in everybody's mind, and then we move ahead to '73, at which point Hatton is leading a team of cattle from Texas to Dodge City, which has firmly ensconced itself as the most important nexus for the cattle industry west of Chicago. And here the actual plot starts to assert itself, though it rarely does it directly: the short version is that Dodge City is an anarchic pit where good men get out as fast as possible and bad men indulge themselves in petty tyranny. The worst of these bad men is Jeff Surrett (Bruce Cabot), who immediately ends up taking a disliking to Hatton when the cowman refuses to accept his offer at auction, knowing a villain when he sees one. It's in part that interpersonal dynamic - but much more a sense of morality when faced with the utter lawlessness of Dodge City, in which not even the smallest child is safe - that leads Hatton to accept the job of sheriff. This makes him just one of several forces working to civilise the place: an ineffective temperance movement, the Pure Prairie League, shows the way, but there's also the newspaper run by Joe Clemens (Frank McHugh), and the symbolic presence of one Abbie Irving (Olivia de Havilland), a hard-working woman of both physical and emotional endurance who stands midway between the prim Pure Prairie Leaguers and the worldly dance hall singer Ruby Gilman (Ann Sheridan).

In short, Dodge City is in part the story of a good man reluctantly standing up against the bad man, bringing the taming influence of The Law where it had previously found no root, and in this respect is like many Westerns before it and even more Westerns after it. But it is also a somewhat abstract story about Dodge City itself, and frontier-era Kansas, and basically the whole matter of the West: the film is far more interested in the social currents under the town than in the mind and body of Wade Hatton. Which may very well be simply a matter of Michael Curtiz being more interested in crowds than in Flynn and de Havilland (the latter of whom was getting fed up with playing beatific ingenues, and lobbied to get Sheridan's role instead; her avowed boredom manifests in her performance every bit as much as Flynn's self-consciousness). It's a very strange, one might even honestly say malformed story: there are numerous digressions and no singular, clear narrative line until the second half. The most apparent of these digressions is a saloon sequence that, I guess, could be defended by showing Surrett's general nastiness: it's a scene that finds Ruby leading a rousing performance of "Marching Through Georgia", to the happy enthusiasm of most of the saloon patrons, until Surrett and his fellow ex-Southerners interrupt with a counter-performance of "Dixie", leading to a barfight that spills out into the street. Hatton never shows up in this sequence, and Surrett's explicit Southernness doesn't matter anywhere else in the film; so why include such a long detour? Simply because, in this moment, what the film finds interesting is the awareness that the Wild West was a melting pot for ex-Union and ex-Confederate forces, and much of the society of the West was the clash between two identities that, officially, no longer existed (though they have proxies: Kansan vs. Texan, townfolk vs. cowboy, Eastern law vs. Western anarchy). The scene itself feels like a clear first attempt at the magnificent "La Marseillaise" scene from Curtiz's later Casablanca; the scenes function differently, and the Dodge City scene is more clumsily executed (primarily in the sound mixing), but the sense of pregnant tension between two irreconcilable, but cohabiting societies is identical.

This is all very much percolating under the surface: for the most part, Dodge City is content to operate at the solitary level of being a fast-paced action movie, in which Flynn trades in swashbuckling for gunslinging to good effect. It's a big splashy Hollywood spectacle, with gorgeous sets and a riot of colors in the costumes and wide-open skies (which range from ludicrously glowing blues to warm sunsets in every hue of red and orange), not a social document, and certainly not a reliable history lesson. But it is, at least, a Hollywood spectacle that takes place at a clearly defined moment in time, dredging up real and important fissures in American society to fuel its conflict, and that background gives it more bite than just any old Western romp. On top of the overall excellence of its production, it's little wonder this film did so much to rejuvenate and legitimise its fading genre.

*As an accident of history, it pleases me that American cinema's greatest single year would be definitive for the most quintessentially American movie genre (give or take the gangster picture).