Blockbuster History: I'm your pusherman

Every week this summer, we'll be taking an historical tour of the Hollywood blockbuster by examining an older film that is in some way a spiritual precursor to one of the weekend's wide releases. This week: to my great chagrin, I have lived on this globe 36 years and more without ever having seen the original film upon which the new Superfly has been based. Hard to imagine a better excuse to finally fix that.

Being Gordon Parks, Jr. and applying yourself to the task of directing a crime drama set among the African-American population of Harlem must be the most incredibly daunting thing. After all, if you are Gordon Parks, Jr, that means your father is Gordon Parks, Sr, and that means your father was one of the co-inventors of the blaxploitation movie when he directed the excellent 1971 thriller Shaft, a film that was an enormous hit that instantaneously set the ground rules for what the genre* would do over its lifespan, such that almost a half-century later, I suspect that it still "is" blaxploitation in the minds of many viewers.

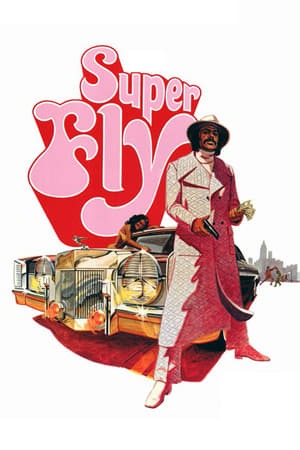

I don't know what genes were involved or if it's just a matter of having a superb role model or what, but Parks fils turned out a 1972 directorial debut almost every inch as good as the old man's work - both in terms of influence and, rather more controversially, I'd say in terms of artistic success, Super Fly is perpetually just a quarter-step behind Shaft in the annals of 1970s urban crime thrillers with unusually complex characters for what looks like unbridled schlock. Admittedly, Super Fly comes with more baggage: even before it was released, activist groups were calling for its head on the grounds that it glamorised the tawdriest stereotypes of African-American culture, and it has through the years accrued a reputation second only to the 1983 Scarface for its glorified depiction of the drug-dealing life as full of extravagance, clothes, cars, and women.

I'd say that it just goes to show that the only way for a film to truly escape the judgment of the Morally Righteous would be to have a scene where the protagonist looks about him and sighs, "oh, look at all the extravagance, clothes, cars, and women in my life! It should make me extraordinarily happy, but it does not - in fact, it makes me sad and empty". Except that I'd be wrong, because Super Fly actually does have that scene. In fact, reputation notwithstanding, the film is a rather mordant character study and social issues drama. The main character, Youngblood Priest (Ron O'Neal), is a highly successful mid-level cocaine dealer in Harlem, who we first meet fending off a couple of junkies looking to mug him. We next see him confronting his indebted client Fat Freddie (Charles McGregor), promising that if Freddie can't pay Priest back soon, Priest is happy to force the man's wife into prostitution to clear the books. Or maybe Freddie can just go commit some violent crimes on Priest's behalf. First impressions are lasting impressions, and Priest has made a hell of a first impression: he's implacable, cold, quite possibly sociopathic.

Nor is it just about the way the character has been written! Priest is a striking figure to look at, not just because of the famously garish coats that are, somehow, one of the film's two most lasting contributions to pop culture (the soundtrack is the other). He's a gaunt figure: at one point, he's derided for being "white-looking", and indeed O'Neal is one of the lightest-skinned members of the cast, but it's more that he looks somewhat dessicated - he doesn't look white, he looks grey. And the actor is sporting a bizarre hairdo: his sideburns are huge, hugging his jawline and pointing to his chin in sharp points, while he has wave shoulder length hair cascading down the sides and back. It's almost like he's got a close-fitting helmet with a wig on top of it. There's something frankly vampiric about Priest's look, made ironic by the omnipresent crucifix necklace he wears (it's a cocaine spoon; the film never comes right out and declares that Priest is himself a helpless addict, but it seems pretty damn clear), and maybe this is all wholly unintentional and I'm an idiot. But it fits: Priest certainly does more harm than good in the world, willingly spreading poison out into an already devastated society and doing his part to keep black people down.

This is all in the background, though it's right up front in the background, so to speak. The actual story is that Priest wants out: the opening encounter with the junkies has clearly rattled him, and has gotten him to thinking about how many ways his life could end given his profession, but that's not really what it feels like. In O'Neal's great, unheralded performance, and aided by that endlessly ironic crucficix, Super Fly is depicting a spiritual malaise: Priest wants out because he is unhappy, and that comes through, silently, in all of the conversations that make up the bulk of the movie. What happens, anyway, is that Priest wants to make one last big score with his partner, Eddie (Carl Lee); they can sock away a million dollars within a few months according to Priest's calculations, and then leave behind dealing for good. But Eddie, the tired and resentful figure who has had all the optimism burned out of him by life as a black man in the United States, isn't eager to see Priest bail on him, and he hangs, vulture-like, over the entire movie, as Priest finds one variation on people telling him, with different levels of good intent, "you can't and shouldn't try to get out of this life". It is a film that, beneath all the trappings of cool, is actually about hopelessness, but an angry, active kind, not a despairing, mournful kind.

It's a pretty strong character study as a result, as well as an excellent snapshot of a small portion of New York at a given moment. The filmmaking is ungainly - the camerawork is frankly shit, with lots of sticky, jerky pans, and unmotivated, wobbly movement; the sound recording is at best rough and fuzzy - but in the best sort of neorealist style, this ends up giving it a substantial feeling of verisimilitude. It's vital filmmaking, woolly and alive, darting along the streets and into buildings with a distinctly wired feeling, as if the movie itself were on the waning end of a coke binge. At one point, Parks breaks from cinema altogether, to present a drug-dealing montage in a series of grainy still photographs, capturing moments in sharp, high-speed stills; it passes into the realm of the elder Parks's documentary photography, so blunt and unstaged that even as it drops movement altogether and falls into a sleek editing scheme of split-screen cutting in time to the extraordinary Curtis Mayfield song "Pusherman" - a deceptively brooding, dark little number, despite its silky melody and Mayfield's even silkier voice, smoothly arguing that to the addict, all meaning devolves to the dealer's wares - it still has the rawness of life, cut into slices and laid bare in the cold light of the projector.

The feeling of an ever-present reality that the film hasn't augmented or dressed up in any way, presented totally without the intervention of style, is maybe the most striking thing about Super Fly: more even than Mayfield's justly legendary soundtrack, aye. Lots of films feel "real", especially lots of films shot in New York in the 1970s. But the very raggedness of Super Fly goes to another level altogether: it has a kind of striking ugliness that matches well with the desperation of its anti-hero hiding just underneath the flash of his daily life. It's thrilling to watch, of course - it wouldn't have picked up its cultural reputation if Priest's life wasn't visually exciting, and O'Neal's performance wasn't vigorously charismatic and sharp - but it has a subdued psychological acuity that goes far beyond the grubby baseline of the normal exploitation film, and makes it a much more rewarding piece of cinema than I think it generally gets credit for.

*If indeed calling blaxploitation a "genre" is right - I feel like it's not, but "cycle" is too clinical and limited, and I'm damned if I can come up with another good word.

Being Gordon Parks, Jr. and applying yourself to the task of directing a crime drama set among the African-American population of Harlem must be the most incredibly daunting thing. After all, if you are Gordon Parks, Jr, that means your father is Gordon Parks, Sr, and that means your father was one of the co-inventors of the blaxploitation movie when he directed the excellent 1971 thriller Shaft, a film that was an enormous hit that instantaneously set the ground rules for what the genre* would do over its lifespan, such that almost a half-century later, I suspect that it still "is" blaxploitation in the minds of many viewers.

I don't know what genes were involved or if it's just a matter of having a superb role model or what, but Parks fils turned out a 1972 directorial debut almost every inch as good as the old man's work - both in terms of influence and, rather more controversially, I'd say in terms of artistic success, Super Fly is perpetually just a quarter-step behind Shaft in the annals of 1970s urban crime thrillers with unusually complex characters for what looks like unbridled schlock. Admittedly, Super Fly comes with more baggage: even before it was released, activist groups were calling for its head on the grounds that it glamorised the tawdriest stereotypes of African-American culture, and it has through the years accrued a reputation second only to the 1983 Scarface for its glorified depiction of the drug-dealing life as full of extravagance, clothes, cars, and women.

I'd say that it just goes to show that the only way for a film to truly escape the judgment of the Morally Righteous would be to have a scene where the protagonist looks about him and sighs, "oh, look at all the extravagance, clothes, cars, and women in my life! It should make me extraordinarily happy, but it does not - in fact, it makes me sad and empty". Except that I'd be wrong, because Super Fly actually does have that scene. In fact, reputation notwithstanding, the film is a rather mordant character study and social issues drama. The main character, Youngblood Priest (Ron O'Neal), is a highly successful mid-level cocaine dealer in Harlem, who we first meet fending off a couple of junkies looking to mug him. We next see him confronting his indebted client Fat Freddie (Charles McGregor), promising that if Freddie can't pay Priest back soon, Priest is happy to force the man's wife into prostitution to clear the books. Or maybe Freddie can just go commit some violent crimes on Priest's behalf. First impressions are lasting impressions, and Priest has made a hell of a first impression: he's implacable, cold, quite possibly sociopathic.

Nor is it just about the way the character has been written! Priest is a striking figure to look at, not just because of the famously garish coats that are, somehow, one of the film's two most lasting contributions to pop culture (the soundtrack is the other). He's a gaunt figure: at one point, he's derided for being "white-looking", and indeed O'Neal is one of the lightest-skinned members of the cast, but it's more that he looks somewhat dessicated - he doesn't look white, he looks grey. And the actor is sporting a bizarre hairdo: his sideburns are huge, hugging his jawline and pointing to his chin in sharp points, while he has wave shoulder length hair cascading down the sides and back. It's almost like he's got a close-fitting helmet with a wig on top of it. There's something frankly vampiric about Priest's look, made ironic by the omnipresent crucifix necklace he wears (it's a cocaine spoon; the film never comes right out and declares that Priest is himself a helpless addict, but it seems pretty damn clear), and maybe this is all wholly unintentional and I'm an idiot. But it fits: Priest certainly does more harm than good in the world, willingly spreading poison out into an already devastated society and doing his part to keep black people down.

This is all in the background, though it's right up front in the background, so to speak. The actual story is that Priest wants out: the opening encounter with the junkies has clearly rattled him, and has gotten him to thinking about how many ways his life could end given his profession, but that's not really what it feels like. In O'Neal's great, unheralded performance, and aided by that endlessly ironic crucficix, Super Fly is depicting a spiritual malaise: Priest wants out because he is unhappy, and that comes through, silently, in all of the conversations that make up the bulk of the movie. What happens, anyway, is that Priest wants to make one last big score with his partner, Eddie (Carl Lee); they can sock away a million dollars within a few months according to Priest's calculations, and then leave behind dealing for good. But Eddie, the tired and resentful figure who has had all the optimism burned out of him by life as a black man in the United States, isn't eager to see Priest bail on him, and he hangs, vulture-like, over the entire movie, as Priest finds one variation on people telling him, with different levels of good intent, "you can't and shouldn't try to get out of this life". It is a film that, beneath all the trappings of cool, is actually about hopelessness, but an angry, active kind, not a despairing, mournful kind.

It's a pretty strong character study as a result, as well as an excellent snapshot of a small portion of New York at a given moment. The filmmaking is ungainly - the camerawork is frankly shit, with lots of sticky, jerky pans, and unmotivated, wobbly movement; the sound recording is at best rough and fuzzy - but in the best sort of neorealist style, this ends up giving it a substantial feeling of verisimilitude. It's vital filmmaking, woolly and alive, darting along the streets and into buildings with a distinctly wired feeling, as if the movie itself were on the waning end of a coke binge. At one point, Parks breaks from cinema altogether, to present a drug-dealing montage in a series of grainy still photographs, capturing moments in sharp, high-speed stills; it passes into the realm of the elder Parks's documentary photography, so blunt and unstaged that even as it drops movement altogether and falls into a sleek editing scheme of split-screen cutting in time to the extraordinary Curtis Mayfield song "Pusherman" - a deceptively brooding, dark little number, despite its silky melody and Mayfield's even silkier voice, smoothly arguing that to the addict, all meaning devolves to the dealer's wares - it still has the rawness of life, cut into slices and laid bare in the cold light of the projector.

The feeling of an ever-present reality that the film hasn't augmented or dressed up in any way, presented totally without the intervention of style, is maybe the most striking thing about Super Fly: more even than Mayfield's justly legendary soundtrack, aye. Lots of films feel "real", especially lots of films shot in New York in the 1970s. But the very raggedness of Super Fly goes to another level altogether: it has a kind of striking ugliness that matches well with the desperation of its anti-hero hiding just underneath the flash of his daily life. It's thrilling to watch, of course - it wouldn't have picked up its cultural reputation if Priest's life wasn't visually exciting, and O'Neal's performance wasn't vigorously charismatic and sharp - but it has a subdued psychological acuity that goes far beyond the grubby baseline of the normal exploitation film, and makes it a much more rewarding piece of cinema than I think it generally gets credit for.

*If indeed calling blaxploitation a "genre" is right - I feel like it's not, but "cycle" is too clinical and limited, and I'm damned if I can come up with another good word.