The films of Miyazaki Hayao: When pigs fly

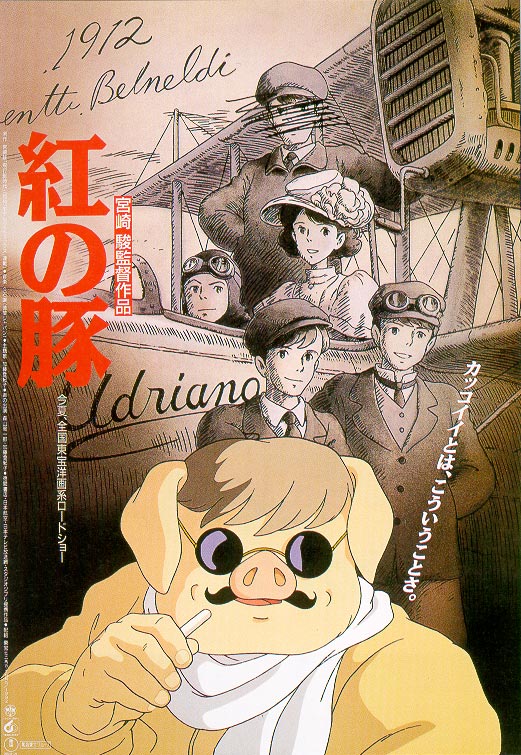

Miyazaki Hayao's sixth feature film grew out of an idea pitched by Japan Airlines, who were looking for a short in-flight movie: "a fun movie for middle-aged businessmen whose brains became tofu from overwork", in the translation provided by the excellent Miyazaki fansite Nausicaa.net. But by the time Porco Rosso was completed, it had far outstripped that relatively modest aim. Like Kiki's Delivery Service before it, the short had exploded to feature length, and outside political elements - namely, the outbreak of war in Yugoslavia, in the very same region that Miyazaki planned to set his story - made the director feel that a more serious film was called for. Not that Porco Rosso isn't still fun, and charming; it's still a cartoon about an animated pig. But there's a serious undercurrent to the story that you'll notice whether you're looking for it or not, and the fantastic narrative is far too demanding and symbolic for tofu-brained businessmen to get nearly as much out of it as it has to say.

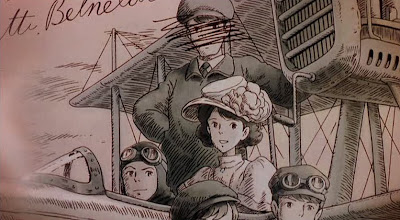

The dominant mode of the film is nostalgia - it is how the main characters all feel about their past life and the present life that is quickly slipping away; it is how the filmmaker evidently feels for the bygone era of adventurous sea pilots and derring-do in the years between the world wars. Miyazaki lets us know everything we need to know in a single image that occurs practically at the very beginning, even before we've seen our protagonist's face.

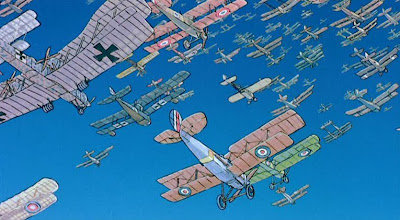

That magazine tells us two things: the year (1929), and the film's eventual indebtedness to cinema history. Far more than any of Miyazaki's other features, before or since, Porco Rosso feels indebted to Western - that is, primarily American - film traditions. It is a film that romanticises '20s pilots all out of proportion, lingering with great satisfaction over their haunts and their craft, while standing back in unabashed glee at the fortitude of the brave souls who fly for a living; even though everyone we see is perfectly mercenary, whether a bounty hunter (the hero) or a pirate (everyone else). Above any other consideration, these are flyboys, those magnificent scoundrels whose greatest love is their plane, and whose home is the open sky. The most famous of all the films in this mode is assuredly Howard Hawks's Only Angels Have Wings released ten years' after Porco Rosso takes place, but the romance extends into the silent era: the first Best Picture winner, 1927's Wings, is just such a story, and examples can be found still earlier.

That magazine tells us two things: the year (1929), and the film's eventual indebtedness to cinema history. Far more than any of Miyazaki's other features, before or since, Porco Rosso feels indebted to Western - that is, primarily American - film traditions. It is a film that romanticises '20s pilots all out of proportion, lingering with great satisfaction over their haunts and their craft, while standing back in unabashed glee at the fortitude of the brave souls who fly for a living; even though everyone we see is perfectly mercenary, whether a bounty hunter (the hero) or a pirate (everyone else). Above any other consideration, these are flyboys, those magnificent scoundrels whose greatest love is their plane, and whose home is the open sky. The most famous of all the films in this mode is assuredly Howard Hawks's Only Angels Have Wings released ten years' after Porco Rosso takes place, but the romance extends into the silent era: the first Best Picture winner, 1927's Wings, is just such a story, and examples can be found still earlier.

One assumes that Miyazaki was a fan of such pictures, for he is a known fan of aviation history. Porco Rosso was based, loosely, on a manga by the director that is very little other than an excuse for him to depict old aircraft in loving watercolors; and of course, one does not need to dig very far into his filmography to find that his love of flying machines and the act of flight is one of the overriding concerns of his career. So maybe a Western, '20s-style plane adventure was an inevitability, though it seems in other ways like an outlier: the only one of Miyazaki's films that takes place in a definite time and place, with specific real-world history that informs the narrative.

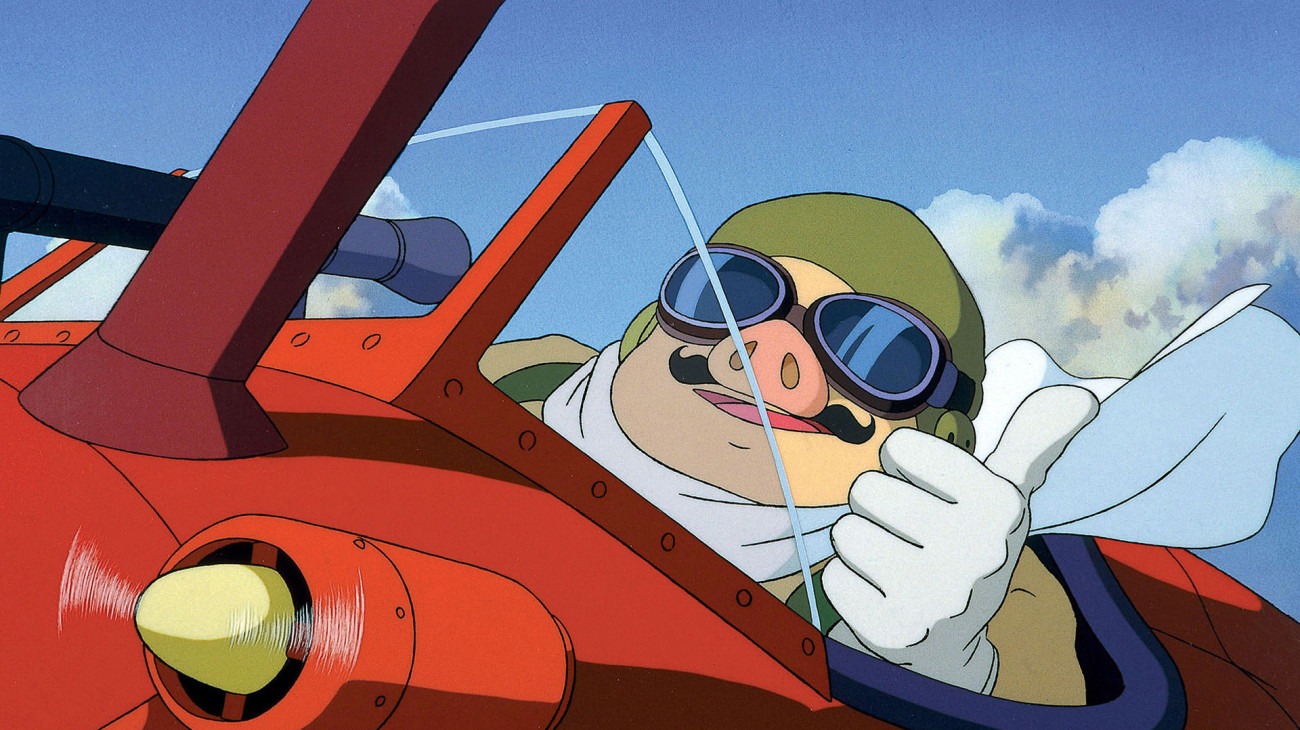

That narrative, I suppose I should say, concerns Porco Rosso (Moriyama Shûichirô) - "Crimson Pig", in Italian - a bounty hunter operating in the Adriatic Sea. By the time the story begins, nobody seems terribly unnerved by the existence of a bipedal pig who acts in all ways like a human, and he's even become something of a legend in those parts as the one hero that no pirate can best - as we see right from the start, when he rather easily takes down the Mamma Aiuto gang (Italian for "Mommy, Help!"), despite an engine that keeps stalling on him. In his down time, Porco relaxes alongside many of those same pirates in the region's designated neutral zone: Hotel Adriano, where all the flyers go to hear the incredible voice of Gina (Katô Tokiko), a woman who's married and lost three pilots in her day. It's thanks to her that we start to pick up clues about Porco's backstory: he used to a human pilot in the Italian Air Force, Marco Pagot (named for Miyzaki's friend and collaborator on Sherlock Hound), who at some point turned into a pig, and has taken great lengths to hide his identity from the world.

Clues are all we'll ever get, and this is the chief respect in which Porco Rosso, for all its similarities to Hollywood adventure stories, is clearly a different thing than they: there is never any concrete explanation for the event that turned Marco into Porco. We can guess that it has to do with the same impulses that led him away from the air force: the experience of losing all his friends in the Great War, and the subsequent rise of the Fascists, whose fetishisation of the military certainly wouldn't sit well with a pilot who was already having grave misgivings about such matters. While this mystery, and its dark political overtones, bubbles on throughout, the film makes at least a stab towards amusing those businessmen, with a story about the cocky American, Donald Curtiss (Ôtsuka Akio), who throws in with the pirates and forms an instant rivalry with Porco, and the pig's budding friendship with 17-year-old Fio Piccolo (Okamura Akemi), the granddaughter of a famed airplane designer who proves to have some very great ideas about design herself.

Clues are all we'll ever get, and this is the chief respect in which Porco Rosso, for all its similarities to Hollywood adventure stories, is clearly a different thing than they: there is never any concrete explanation for the event that turned Marco into Porco. We can guess that it has to do with the same impulses that led him away from the air force: the experience of losing all his friends in the Great War, and the subsequent rise of the Fascists, whose fetishisation of the military certainly wouldn't sit well with a pilot who was already having grave misgivings about such matters. While this mystery, and its dark political overtones, bubbles on throughout, the film makes at least a stab towards amusing those businessmen, with a story about the cocky American, Donald Curtiss (Ôtsuka Akio), who throws in with the pirates and forms an instant rivalry with Porco, and the pig's budding friendship with 17-year-old Fio Piccolo (Okamura Akemi), the granddaughter of a famed airplane designer who proves to have some very great ideas about design herself.

That a pretty great adventure movie can rest comfortably alongside a strange tale of identity and morality that is itself set against the rise of Fascism is proof enough that we're in the hands of a master storyteller, and of course there's the matter of how Miyazaki the animator uses his medium to so beautifully evoke his beloved airplanes: their shape, and the miracle of flight.

Unlike some of the director's more A-list projects, the beauty of Porco Rosso lies not in its depiction of the fantastic and the impossible, but of the historic. You could argue, with a minimum of difficulty, that Miyazaki is really just indulging himself here, no different in his ultimate intent than any given fanboy in making a short film filled with Star Wars in-jokes. The difference is that Miyazaki has the artistry to match his passion, and so he makes his obsessions our obsessions. I defy any viewer to leave Porco Rosso without having sighed at least once that the glory days of flyboys are resigned to a dusty corner of modern history. That is what Miyazaki's love does: transform something already romantic into something legendary and epic.

Unlike some of the director's more A-list projects, the beauty of Porco Rosso lies not in its depiction of the fantastic and the impossible, but of the historic. You could argue, with a minimum of difficulty, that Miyazaki is really just indulging himself here, no different in his ultimate intent than any given fanboy in making a short film filled with Star Wars in-jokes. The difference is that Miyazaki has the artistry to match his passion, and so he makes his obsessions our obsessions. I defy any viewer to leave Porco Rosso without having sighed at least once that the glory days of flyboys are resigned to a dusty corner of modern history. That is what Miyazaki's love does: transform something already romantic into something legendary and epic.

The film is no shallow bit of praise for the past, though: in a very real sense, he is trying to examine the birth of the contemporary world by looking at how it was formed. Fascism, in the movie, is little more than a nuisance to the characters; but the viewer knows - or damned well ought to - that the Fascists were shortly to raise arms in the hideously bloody conflict that would define the second half of the 20th Century. By taking a snapshot of a moment just before the Fascists' schemes went from the local to the global, Miyazaki provides us with a reminder that events don't come from nothing; history is an iterative process.

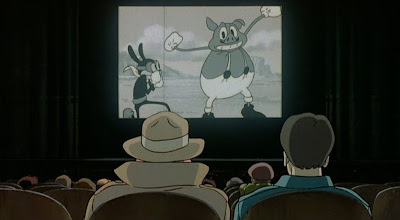

He even applies this level or analysis to his own artform, in a low-key but tremendously memorable sequence where Porco watches a cartoon, in which a villainous aviator pig (who bears a notable resemblance to Porco himself) kidnaps a cat and is comically beaten up by the cat's ambiguously canine boyfriend. It's theoretically a new film in 1929, but the contrast between Miyazaki's representation of late-'20s "rubber tube" animation (with a Winsor McKay dino thrown in just for fun), and his own anime aesthetic is stunningly effective in a tiny way, to remind us once again that where we are is the result of where we've come from.

By no means is Porco Rosso a dry, intellectual exercise, nor is it a depressing story of war and morality; those are just the undercurrents. On a more immediate level, this is another in the director's yet-uninterrupted string of marvelous fantasies that are as delightful and thrilling as they are emotionally powerful; though I can't carry that argument far enough that I won't also state, emphatically, that this is Miyazaki's most un-childlike film - if he ever made a "grown-up animation", to use a phrase that I suppose would anger him greatly, it's this one. But grown-up or not, it's still a blissful fantasy/adventure movie, not that at this point I need to keep mentioning that. Miyazaki makes blissful fantasy/adventure movies like other people make pancakes, and Porco Rosso merely finds him proving that neither genre, historical veracity, nor philosophy can stand between him and a really damn great cartoon.

By no means is Porco Rosso a dry, intellectual exercise, nor is it a depressing story of war and morality; those are just the undercurrents. On a more immediate level, this is another in the director's yet-uninterrupted string of marvelous fantasies that are as delightful and thrilling as they are emotionally powerful; though I can't carry that argument far enough that I won't also state, emphatically, that this is Miyazaki's most un-childlike film - if he ever made a "grown-up animation", to use a phrase that I suppose would anger him greatly, it's this one. But grown-up or not, it's still a blissful fantasy/adventure movie, not that at this point I need to keep mentioning that. Miyazaki makes blissful fantasy/adventure movies like other people make pancakes, and Porco Rosso merely finds him proving that neither genre, historical veracity, nor philosophy can stand between him and a really damn great cartoon.

The dominant mode of the film is nostalgia - it is how the main characters all feel about their past life and the present life that is quickly slipping away; it is how the filmmaker evidently feels for the bygone era of adventurous sea pilots and derring-do in the years between the world wars. Miyazaki lets us know everything we need to know in a single image that occurs practically at the very beginning, even before we've seen our protagonist's face.

That magazine tells us two things: the year (1929), and the film's eventual indebtedness to cinema history. Far more than any of Miyazaki's other features, before or since, Porco Rosso feels indebted to Western - that is, primarily American - film traditions. It is a film that romanticises '20s pilots all out of proportion, lingering with great satisfaction over their haunts and their craft, while standing back in unabashed glee at the fortitude of the brave souls who fly for a living; even though everyone we see is perfectly mercenary, whether a bounty hunter (the hero) or a pirate (everyone else). Above any other consideration, these are flyboys, those magnificent scoundrels whose greatest love is their plane, and whose home is the open sky. The most famous of all the films in this mode is assuredly Howard Hawks's Only Angels Have Wings released ten years' after Porco Rosso takes place, but the romance extends into the silent era: the first Best Picture winner, 1927's Wings, is just such a story, and examples can be found still earlier.

That magazine tells us two things: the year (1929), and the film's eventual indebtedness to cinema history. Far more than any of Miyazaki's other features, before or since, Porco Rosso feels indebted to Western - that is, primarily American - film traditions. It is a film that romanticises '20s pilots all out of proportion, lingering with great satisfaction over their haunts and their craft, while standing back in unabashed glee at the fortitude of the brave souls who fly for a living; even though everyone we see is perfectly mercenary, whether a bounty hunter (the hero) or a pirate (everyone else). Above any other consideration, these are flyboys, those magnificent scoundrels whose greatest love is their plane, and whose home is the open sky. The most famous of all the films in this mode is assuredly Howard Hawks's Only Angels Have Wings released ten years' after Porco Rosso takes place, but the romance extends into the silent era: the first Best Picture winner, 1927's Wings, is just such a story, and examples can be found still earlier.One assumes that Miyazaki was a fan of such pictures, for he is a known fan of aviation history. Porco Rosso was based, loosely, on a manga by the director that is very little other than an excuse for him to depict old aircraft in loving watercolors; and of course, one does not need to dig very far into his filmography to find that his love of flying machines and the act of flight is one of the overriding concerns of his career. So maybe a Western, '20s-style plane adventure was an inevitability, though it seems in other ways like an outlier: the only one of Miyazaki's films that takes place in a definite time and place, with specific real-world history that informs the narrative.

That narrative, I suppose I should say, concerns Porco Rosso (Moriyama Shûichirô) - "Crimson Pig", in Italian - a bounty hunter operating in the Adriatic Sea. By the time the story begins, nobody seems terribly unnerved by the existence of a bipedal pig who acts in all ways like a human, and he's even become something of a legend in those parts as the one hero that no pirate can best - as we see right from the start, when he rather easily takes down the Mamma Aiuto gang (Italian for "Mommy, Help!"), despite an engine that keeps stalling on him. In his down time, Porco relaxes alongside many of those same pirates in the region's designated neutral zone: Hotel Adriano, where all the flyers go to hear the incredible voice of Gina (Katô Tokiko), a woman who's married and lost three pilots in her day. It's thanks to her that we start to pick up clues about Porco's backstory: he used to a human pilot in the Italian Air Force, Marco Pagot (named for Miyzaki's friend and collaborator on Sherlock Hound), who at some point turned into a pig, and has taken great lengths to hide his identity from the world.

Clues are all we'll ever get, and this is the chief respect in which Porco Rosso, for all its similarities to Hollywood adventure stories, is clearly a different thing than they: there is never any concrete explanation for the event that turned Marco into Porco. We can guess that it has to do with the same impulses that led him away from the air force: the experience of losing all his friends in the Great War, and the subsequent rise of the Fascists, whose fetishisation of the military certainly wouldn't sit well with a pilot who was already having grave misgivings about such matters. While this mystery, and its dark political overtones, bubbles on throughout, the film makes at least a stab towards amusing those businessmen, with a story about the cocky American, Donald Curtiss (Ôtsuka Akio), who throws in with the pirates and forms an instant rivalry with Porco, and the pig's budding friendship with 17-year-old Fio Piccolo (Okamura Akemi), the granddaughter of a famed airplane designer who proves to have some very great ideas about design herself.

Clues are all we'll ever get, and this is the chief respect in which Porco Rosso, for all its similarities to Hollywood adventure stories, is clearly a different thing than they: there is never any concrete explanation for the event that turned Marco into Porco. We can guess that it has to do with the same impulses that led him away from the air force: the experience of losing all his friends in the Great War, and the subsequent rise of the Fascists, whose fetishisation of the military certainly wouldn't sit well with a pilot who was already having grave misgivings about such matters. While this mystery, and its dark political overtones, bubbles on throughout, the film makes at least a stab towards amusing those businessmen, with a story about the cocky American, Donald Curtiss (Ôtsuka Akio), who throws in with the pirates and forms an instant rivalry with Porco, and the pig's budding friendship with 17-year-old Fio Piccolo (Okamura Akemi), the granddaughter of a famed airplane designer who proves to have some very great ideas about design herself.That a pretty great adventure movie can rest comfortably alongside a strange tale of identity and morality that is itself set against the rise of Fascism is proof enough that we're in the hands of a master storyteller, and of course there's the matter of how Miyazaki the animator uses his medium to so beautifully evoke his beloved airplanes: their shape, and the miracle of flight.

Unlike some of the director's more A-list projects, the beauty of Porco Rosso lies not in its depiction of the fantastic and the impossible, but of the historic. You could argue, with a minimum of difficulty, that Miyazaki is really just indulging himself here, no different in his ultimate intent than any given fanboy in making a short film filled with Star Wars in-jokes. The difference is that Miyazaki has the artistry to match his passion, and so he makes his obsessions our obsessions. I defy any viewer to leave Porco Rosso without having sighed at least once that the glory days of flyboys are resigned to a dusty corner of modern history. That is what Miyazaki's love does: transform something already romantic into something legendary and epic.

Unlike some of the director's more A-list projects, the beauty of Porco Rosso lies not in its depiction of the fantastic and the impossible, but of the historic. You could argue, with a minimum of difficulty, that Miyazaki is really just indulging himself here, no different in his ultimate intent than any given fanboy in making a short film filled with Star Wars in-jokes. The difference is that Miyazaki has the artistry to match his passion, and so he makes his obsessions our obsessions. I defy any viewer to leave Porco Rosso without having sighed at least once that the glory days of flyboys are resigned to a dusty corner of modern history. That is what Miyazaki's love does: transform something already romantic into something legendary and epic.The film is no shallow bit of praise for the past, though: in a very real sense, he is trying to examine the birth of the contemporary world by looking at how it was formed. Fascism, in the movie, is little more than a nuisance to the characters; but the viewer knows - or damned well ought to - that the Fascists were shortly to raise arms in the hideously bloody conflict that would define the second half of the 20th Century. By taking a snapshot of a moment just before the Fascists' schemes went from the local to the global, Miyazaki provides us with a reminder that events don't come from nothing; history is an iterative process.

He even applies this level or analysis to his own artform, in a low-key but tremendously memorable sequence where Porco watches a cartoon, in which a villainous aviator pig (who bears a notable resemblance to Porco himself) kidnaps a cat and is comically beaten up by the cat's ambiguously canine boyfriend. It's theoretically a new film in 1929, but the contrast between Miyazaki's representation of late-'20s "rubber tube" animation (with a Winsor McKay dino thrown in just for fun), and his own anime aesthetic is stunningly effective in a tiny way, to remind us once again that where we are is the result of where we've come from.

By no means is Porco Rosso a dry, intellectual exercise, nor is it a depressing story of war and morality; those are just the undercurrents. On a more immediate level, this is another in the director's yet-uninterrupted string of marvelous fantasies that are as delightful and thrilling as they are emotionally powerful; though I can't carry that argument far enough that I won't also state, emphatically, that this is Miyazaki's most un-childlike film - if he ever made a "grown-up animation", to use a phrase that I suppose would anger him greatly, it's this one. But grown-up or not, it's still a blissful fantasy/adventure movie, not that at this point I need to keep mentioning that. Miyazaki makes blissful fantasy/adventure movies like other people make pancakes, and Porco Rosso merely finds him proving that neither genre, historical veracity, nor philosophy can stand between him and a really damn great cartoon.

By no means is Porco Rosso a dry, intellectual exercise, nor is it a depressing story of war and morality; those are just the undercurrents. On a more immediate level, this is another in the director's yet-uninterrupted string of marvelous fantasies that are as delightful and thrilling as they are emotionally powerful; though I can't carry that argument far enough that I won't also state, emphatically, that this is Miyazaki's most un-childlike film - if he ever made a "grown-up animation", to use a phrase that I suppose would anger him greatly, it's this one. But grown-up or not, it's still a blissful fantasy/adventure movie, not that at this point I need to keep mentioning that. Miyazaki makes blissful fantasy/adventure movies like other people make pancakes, and Porco Rosso merely finds him proving that neither genre, historical veracity, nor philosophy can stand between him and a really damn great cartoon.