I think I'd rather be a cowboy

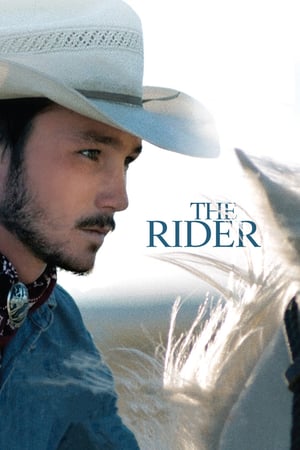

The Rider isn't sensu stricto a biopic of its star, Brady Jandreau, but it's a pretty fine line. Jandreau was an up-and-coming rodeo star out of South Dakota when he fell off a bronco he was riding and suffered a debilitating brain injury, and there's not a single word of that sentence that doesn't also apply to his character, Brady Blackburn. Add in the fact that Jandreau's father Tim plays Brady's father Wayne, and Jandreau's sister Lilly plays Brady's sister Lilly, and the rest of the main characters in the film are played by people sharing their names with their characters, without even the fig leaf of their surnames being changed, and writer-director Chloé Zhao's idea comes out about as clear as could be. This isn't just one of those art films where non-professional actors are brought in to provide that certain sense of raw, unstudied authenticity; it is the most authentic, because the assembled cast doesn't even have to "act", but simply inhabit space.

Like pretty much every attempt at doing this in the last 70 years, I found the results quite conclusive: acting is best left to actors, lest you get this kind of shiftless, awkwardly mumbling emptiness going on for the entire length of a very drearily slow-moving movie. I am aware that in this particular case, at least, I am on the wrong side of history and the overwhelming critical consensus, and I am totally fine with that. The Rider is deeply tedious and superficial in its treatment of nearly all its themes, and its commitment to letting Jandreau shuffle his way across 104 extremely long minutes tells me not nearly as much about the cultural milieu of American men in the modern West as Zhao self-evidently believes that it does.

The basic thrust of the film is that Brady only knows how to do two things - ride horses and break wild horses - and in the wake of his accident, which has left him plagued by a form of seizure that manifests in the form of his right hand uncontrollably clenching, those are the only two things he absolutely must not do. The Rider doesn't have much in the way of a story, but what it has centers on his attempts to find something else to do, while constantly trying to test exactly how much riding is too much riding, like a child moving inch by inch closer to a cookie jar, eyes glued to his mother. He is encouraged in this self-destructive pursuit by his buddies, who ebulliently talk about how being a man means fighting through the pain. That Zhao means for this to be a sympathetic indictment of the masculine code of the American West is clear (with an added layer of unstressed irony that the film takes place and was shot in the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation, meaning that all of the men idealising cowboy culture are the descendants of people who were slaughtered by that culture), though The Rider doesn't go any deeper into this indictment than pointing out that it is, in fact, bad to be peer pressured into self-destructive behavior.

For the most part, though, the film is largely content to putter along in a state of relaxed watchfulness: it is mostly interested in watching Brady go about his aimless, uncertain days. It is an extraordinarily passive film, centered on an extraordinarily passive performance, and I suppose if "realism" is in and of itself a goal, rather than a means to an end, The Rider is successful. The sheer lack of momentum grows wearisome pretty quickly, however, and though Zhao and cinematographer Joshua James Richardson hand him many of pensive close-ups from interestingly acute angles, Jandreau is nowhere near strong enough of a screen presence to hold interest during the film's longueurs. There's always a danger in having a protagonist defined by his lack of action and inability to articulate his psychology, in that it leads fairly naturally to a non-dramatic, superficial act of staring at boring people, and The Rider compounds this with a lead actor who is almost being specifically asked not to compensate for these things.

I'm being very grumpy about a film that's far too small to have asked for it, so allow me to switch gears and talk about what the film actually does well. It's often quite beautiful: this is Zhao and Richardson's second collaboration shot in South Dakota, and they've figured out a lot of the wonderful things that can be done with the flatness of the grassland, and the blindingly clear sunlight. There are stunning backlit shots of Brady as an indefinite black smear against the landscape; there are rampant sunsets bathing the world in warm but fading oranges. It's a film whose visuals are softly elegiac in ways its script hasn't entirely thought about being, and if Jandreau can't quite put across Brady's inarticulate sense of yearning loss, the imagery does plenty of work for him. In a very different way, the same thing is achieved during the film's several moments of a kind of naturalistic extremity: the badly chapped nose of a horse, the deeply nauseating scene of Brady steadily pulling staples out of his skull, a bloody and torn-up limb. The thing I was least prepared for was how viscerally gruesome parts of The Rider would be, and the totally unfussed way the characters work within that gruesomeness tells us more about the world they live in and how they navigate it than all the rest of the movie combined, even as they make it almost completely undenurable to sit through it in little ten and fifteen-second chunks.

The film also snaps into sharp focus when it more or less abandons its conceit of being fiction and entirely gives itself over to docudrama. Its best scene, by a commanding margin, finds Brady working with an untrained colt in a shabby wooden pen, and we're basically watching Jandreah break a horse in front of our very eyes. It's one of the view moments of actual doing in the film, when the actions of the characters and the slow rhythm work to help clarify emotions and the film's vague character arc.

More moments like that, and we'd have something. Instead, the film is just so damn neutral, and dare I use the word, boring. The hands-off approach is admirable in a vacuum, but this is hands-off to the point of dysfunction. Worse even than boring is when this docudrama style results in the borderline exploitation of Lilly Jandreau (whose character, at least, is developmentally disabled) and Lane Scott, a rodeo Wunderkind who suffered a terrible accident that has left him barely able to control his body at all, and who is used in the film basically as a Jacob Marley character. The way that these people serve as mirrors to Brady's broken head that rankles: misery porn is bad enough, but misery porn that uses real-life trauma as narrative symbolism is just out-and-out distasteful. This is by no means the film's primary mode, but it happens enough that one is grateful when the movie has the decency to go back to being simply pointless.

Like pretty much every attempt at doing this in the last 70 years, I found the results quite conclusive: acting is best left to actors, lest you get this kind of shiftless, awkwardly mumbling emptiness going on for the entire length of a very drearily slow-moving movie. I am aware that in this particular case, at least, I am on the wrong side of history and the overwhelming critical consensus, and I am totally fine with that. The Rider is deeply tedious and superficial in its treatment of nearly all its themes, and its commitment to letting Jandreau shuffle his way across 104 extremely long minutes tells me not nearly as much about the cultural milieu of American men in the modern West as Zhao self-evidently believes that it does.

The basic thrust of the film is that Brady only knows how to do two things - ride horses and break wild horses - and in the wake of his accident, which has left him plagued by a form of seizure that manifests in the form of his right hand uncontrollably clenching, those are the only two things he absolutely must not do. The Rider doesn't have much in the way of a story, but what it has centers on his attempts to find something else to do, while constantly trying to test exactly how much riding is too much riding, like a child moving inch by inch closer to a cookie jar, eyes glued to his mother. He is encouraged in this self-destructive pursuit by his buddies, who ebulliently talk about how being a man means fighting through the pain. That Zhao means for this to be a sympathetic indictment of the masculine code of the American West is clear (with an added layer of unstressed irony that the film takes place and was shot in the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation, meaning that all of the men idealising cowboy culture are the descendants of people who were slaughtered by that culture), though The Rider doesn't go any deeper into this indictment than pointing out that it is, in fact, bad to be peer pressured into self-destructive behavior.

For the most part, though, the film is largely content to putter along in a state of relaxed watchfulness: it is mostly interested in watching Brady go about his aimless, uncertain days. It is an extraordinarily passive film, centered on an extraordinarily passive performance, and I suppose if "realism" is in and of itself a goal, rather than a means to an end, The Rider is successful. The sheer lack of momentum grows wearisome pretty quickly, however, and though Zhao and cinematographer Joshua James Richardson hand him many of pensive close-ups from interestingly acute angles, Jandreau is nowhere near strong enough of a screen presence to hold interest during the film's longueurs. There's always a danger in having a protagonist defined by his lack of action and inability to articulate his psychology, in that it leads fairly naturally to a non-dramatic, superficial act of staring at boring people, and The Rider compounds this with a lead actor who is almost being specifically asked not to compensate for these things.

I'm being very grumpy about a film that's far too small to have asked for it, so allow me to switch gears and talk about what the film actually does well. It's often quite beautiful: this is Zhao and Richardson's second collaboration shot in South Dakota, and they've figured out a lot of the wonderful things that can be done with the flatness of the grassland, and the blindingly clear sunlight. There are stunning backlit shots of Brady as an indefinite black smear against the landscape; there are rampant sunsets bathing the world in warm but fading oranges. It's a film whose visuals are softly elegiac in ways its script hasn't entirely thought about being, and if Jandreau can't quite put across Brady's inarticulate sense of yearning loss, the imagery does plenty of work for him. In a very different way, the same thing is achieved during the film's several moments of a kind of naturalistic extremity: the badly chapped nose of a horse, the deeply nauseating scene of Brady steadily pulling staples out of his skull, a bloody and torn-up limb. The thing I was least prepared for was how viscerally gruesome parts of The Rider would be, and the totally unfussed way the characters work within that gruesomeness tells us more about the world they live in and how they navigate it than all the rest of the movie combined, even as they make it almost completely undenurable to sit through it in little ten and fifteen-second chunks.

The film also snaps into sharp focus when it more or less abandons its conceit of being fiction and entirely gives itself over to docudrama. Its best scene, by a commanding margin, finds Brady working with an untrained colt in a shabby wooden pen, and we're basically watching Jandreah break a horse in front of our very eyes. It's one of the view moments of actual doing in the film, when the actions of the characters and the slow rhythm work to help clarify emotions and the film's vague character arc.

More moments like that, and we'd have something. Instead, the film is just so damn neutral, and dare I use the word, boring. The hands-off approach is admirable in a vacuum, but this is hands-off to the point of dysfunction. Worse even than boring is when this docudrama style results in the borderline exploitation of Lilly Jandreau (whose character, at least, is developmentally disabled) and Lane Scott, a rodeo Wunderkind who suffered a terrible accident that has left him barely able to control his body at all, and who is used in the film basically as a Jacob Marley character. The way that these people serve as mirrors to Brady's broken head that rankles: misery porn is bad enough, but misery porn that uses real-life trauma as narrative symbolism is just out-and-out distasteful. This is by no means the film's primary mode, but it happens enough that one is grateful when the movie has the decency to go back to being simply pointless.