Fear and self-loathing

The films of Noah Baumbach are extremely divisive: between those who find the characters in his scripts so vile that you can't stand watching them, and those who find the characters so vile that it's brave and bracing. Do please note that there is no phantom third variety of people who find his characters pleasant and likable and interesting.

So it is with Greenberg, the writer-director's sixth feature, and his latest representation of how inexpressibly awful a sufficiently broken human being can be to others, even the ones he tries to love the most. Or as someone in the film puts it, "hurt people hurt people", which would make a good inscription for Baumbach's tombstone. Much as he did with the characters in The Squid and the Whale (an unpleasant upper-middle class New York family) and Margot at the Wedding (a viscerally unpleasant upper-middle class New York family), Baumbach here presents the titular Roger Greenberg, played by an uncanny Ben Stiller, as a man who has been screwed over by life, partially because of his own bad decisions and partially just from really tough luck, who wants nothing more than another human being to connect to - except that whatever part of a person allows him to have empathy, sympathy, even mere social politeness, that part of Roger has been long since withered away from misuse.

Roger is a New Yorker, of upper-middle class upbringing, who has just been released from a mental institution (we never learn why he was there, though apparently he had an anxiety attack so intense it briefly left him a psychosomatic paraplegic), and is visiting his onetime home of Los Angeles, housesitting for his brother (Chris Messina) while the more affluent West Coast Greenbergs are on vacation in Vietnam. Here he meets their personal assistant, Florence Marr (Greta Gerwig), while also trying in a badly fumbling way to reconnect with his old friends, especially his former bandmate, Ivan Schrank (Rhys Ifans). Not to go into the details - though by all means, the film's soul is in the details, and not in the plot outline - Roger and Florence hook-up despite a significant age gap (she's 25, he's just turned 41), despite because she's almost as damaged as he is, though in a very different way, that's not remotely as implosive.

Getting the important part out of the way first: we do not like Roger Greenberg. But maybe (and this is what divides people who enjoy Greenberg from people who don't) we feel sorry for him, a little bit. Not much; for whatever happened in his past, he brings all of his current woes upon himself His seduction of Florence, though that is not even slightly the word for it, is clumsy and awkward at its least cringe-inducing moments; brutal and casually cruel more often. Their first, aborted sexual encounter is deeply embarrassing to watch, as on the one hand Roger paws at Florence without feeling or tact, and on the other, she responds to this clumsy, middle-school come-on by apologising that she isn't wearing a pretty bra. As their relationship progresses, it curdles: he snaps and pouts at nothing, she keeps coming back without realising - or, perhaps more likely, caring - that he lacks the capacity for tenderness or emotional intimacy. "Are you going to let me in?" is the film's opening mantra, spoken by Florence as she tries to merge into traffic; the answer, hammered home again and again, a little sicker and nastier in every iteration, is "Absolutely not".

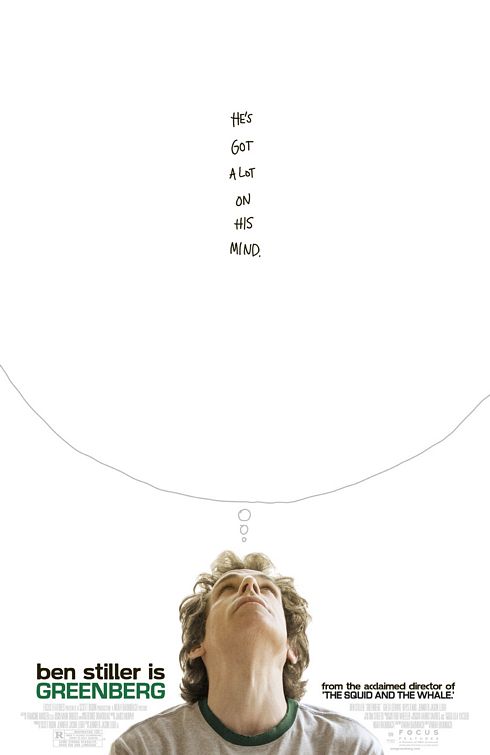

It's an acidic, itchy character study, not as writhing and merciless as Margot at the Wedding, but still much more discomfiting than it is funny (there are laughs, but not any real humor, if that makes sense), largely because of its surgical precision. Baumbach's misanthropy may have become shtick by this point, but he keeps returning to the same mode because he's so unbelievably good at it, and his unblinking depiction of Roger is a sort of genius. Certainly, casting Ben Stiller was an incredible stroke of fortune, and to a large extent the character was written around him; like Adam Sandler in Punch-Drunk Love, this is partially an exercise in watch what happens when a comic actor's given persona (in Stiller's case, braggadocio and a sarcastic smugness that he's the smartest guy in any room) is taken out of farce and put into reality. It's not pretty: but it's arresting, and horrifying, and sad. That Stiller is better than his scripts isn't news, but still, it's quite a thing to have such a potent reminder of what he can bring to a performance when he decides to act. Here, his physical embodiment of Roger is just as important as anything else: with a crop of ratty, shaggy hair, a gaunt look, and a tendency to stare with way too much unthinking intensity, the character is uncomfortable just to watch; he must be hell to be around. That's certainly the sense of the movie's best scene, in which Roger and his ex-girlfriend, Beth (Jennifer Jason Leigh) meet for coffee. The pas de deux between the two actors, with Beth constantly trying to politely wiggle out of what is plainly an excruciating moment, and Roger dropping in front of her like a brick wall every time. The scene is a brilliant showcase for Leigh (Baumbach's wife and Greenberg's story writer), who in a role that's not much bigger than a cameo gives one of the most indelible performances in months, a year or two even, but Stiller holds his own, and the cumulative power of the moment is the best example in the film of just what is the cost to both Roger and those around him of his terrible neuroses.

Gerwig herself isn't any slouch; she's come a long way from Joe Swanberg's excruciating Hannah Takes the Stairs, to play a real character that fits her apparent limitations like a glove. Only in Hollywood would Gerwig be considered "fat", but she has a kind of fleshy quality, coupled with her character's apparent inability to think of herself as a person who deserves to look nice (her own mantra is "You are of value", a depressingly clinical sort of positive reinforcement), and just as Stiller's physical presence largely define Roger, so does Gerwig's define Florence; if he's strung out, she's slumped. We never feel quite as much need to blame her for her sins as we do him, but at the same time, she's harder to sympathise with; she projects so little personality into the universe that it's difficult to care about her.

The ways that Baumbach explores these worn-out characters is varied and deceptively simple: through music (some of it provided by James Murphy, some of it pre-existing pop music; there's a magnificent scene set to "Admiral Halsey" by Paul and Linda McCartney), though Harris Savides's outstanding cinematography, which renders Los Angeles as a dusty, grainy, indistinct place where it's always warm and never hot, and certainly never livable (I cannot name a soul who uses Southern California's unique light better than Savides), and through a careful use of close-ups: not indiscriminately and messily, but as punctuation. The fabric of the movie keeps pushing us in towards Roger, never letting us a safe distance, always making us share in his nastiness along with his victims. It is merciless, and therefore extremely effective.

All in all: a fun night at the movies! That's the only real problem though; along with Margot at the Wedding (and unlike The Squid and the Whale, or Baumbach's earlier, non-misanthropic features), I can't really say what Greenberg does of especial value to the randomly-selected viewer. A good character study is arguably its own reward, of course, and we certainly do get to learn quite a lot about human behavior from Greenberg, most of it unpleasant. This is not a film about redemption or happy romance; though it ends in such a way that we can assume that Roger and Florence might be together, we can't for more than a moment believe that it would be very happy or remotely healthy. The film begins and ends with saying, "This kind of self-destructive person exists, there's not much you can do to save them, only keep them from taking you down too", which is of course the truth. And maybe, as long as Baumbach seems mostly alone amongst American filmmakers in telling that kind of story, he doesn't need to have a better reason for doing so.

So it is with Greenberg, the writer-director's sixth feature, and his latest representation of how inexpressibly awful a sufficiently broken human being can be to others, even the ones he tries to love the most. Or as someone in the film puts it, "hurt people hurt people", which would make a good inscription for Baumbach's tombstone. Much as he did with the characters in The Squid and the Whale (an unpleasant upper-middle class New York family) and Margot at the Wedding (a viscerally unpleasant upper-middle class New York family), Baumbach here presents the titular Roger Greenberg, played by an uncanny Ben Stiller, as a man who has been screwed over by life, partially because of his own bad decisions and partially just from really tough luck, who wants nothing more than another human being to connect to - except that whatever part of a person allows him to have empathy, sympathy, even mere social politeness, that part of Roger has been long since withered away from misuse.

Roger is a New Yorker, of upper-middle class upbringing, who has just been released from a mental institution (we never learn why he was there, though apparently he had an anxiety attack so intense it briefly left him a psychosomatic paraplegic), and is visiting his onetime home of Los Angeles, housesitting for his brother (Chris Messina) while the more affluent West Coast Greenbergs are on vacation in Vietnam. Here he meets their personal assistant, Florence Marr (Greta Gerwig), while also trying in a badly fumbling way to reconnect with his old friends, especially his former bandmate, Ivan Schrank (Rhys Ifans). Not to go into the details - though by all means, the film's soul is in the details, and not in the plot outline - Roger and Florence hook-up despite a significant age gap (she's 25, he's just turned 41), despite because she's almost as damaged as he is, though in a very different way, that's not remotely as implosive.

Getting the important part out of the way first: we do not like Roger Greenberg. But maybe (and this is what divides people who enjoy Greenberg from people who don't) we feel sorry for him, a little bit. Not much; for whatever happened in his past, he brings all of his current woes upon himself His seduction of Florence, though that is not even slightly the word for it, is clumsy and awkward at its least cringe-inducing moments; brutal and casually cruel more often. Their first, aborted sexual encounter is deeply embarrassing to watch, as on the one hand Roger paws at Florence without feeling or tact, and on the other, she responds to this clumsy, middle-school come-on by apologising that she isn't wearing a pretty bra. As their relationship progresses, it curdles: he snaps and pouts at nothing, she keeps coming back without realising - or, perhaps more likely, caring - that he lacks the capacity for tenderness or emotional intimacy. "Are you going to let me in?" is the film's opening mantra, spoken by Florence as she tries to merge into traffic; the answer, hammered home again and again, a little sicker and nastier in every iteration, is "Absolutely not".

It's an acidic, itchy character study, not as writhing and merciless as Margot at the Wedding, but still much more discomfiting than it is funny (there are laughs, but not any real humor, if that makes sense), largely because of its surgical precision. Baumbach's misanthropy may have become shtick by this point, but he keeps returning to the same mode because he's so unbelievably good at it, and his unblinking depiction of Roger is a sort of genius. Certainly, casting Ben Stiller was an incredible stroke of fortune, and to a large extent the character was written around him; like Adam Sandler in Punch-Drunk Love, this is partially an exercise in watch what happens when a comic actor's given persona (in Stiller's case, braggadocio and a sarcastic smugness that he's the smartest guy in any room) is taken out of farce and put into reality. It's not pretty: but it's arresting, and horrifying, and sad. That Stiller is better than his scripts isn't news, but still, it's quite a thing to have such a potent reminder of what he can bring to a performance when he decides to act. Here, his physical embodiment of Roger is just as important as anything else: with a crop of ratty, shaggy hair, a gaunt look, and a tendency to stare with way too much unthinking intensity, the character is uncomfortable just to watch; he must be hell to be around. That's certainly the sense of the movie's best scene, in which Roger and his ex-girlfriend, Beth (Jennifer Jason Leigh) meet for coffee. The pas de deux between the two actors, with Beth constantly trying to politely wiggle out of what is plainly an excruciating moment, and Roger dropping in front of her like a brick wall every time. The scene is a brilliant showcase for Leigh (Baumbach's wife and Greenberg's story writer), who in a role that's not much bigger than a cameo gives one of the most indelible performances in months, a year or two even, but Stiller holds his own, and the cumulative power of the moment is the best example in the film of just what is the cost to both Roger and those around him of his terrible neuroses.

Gerwig herself isn't any slouch; she's come a long way from Joe Swanberg's excruciating Hannah Takes the Stairs, to play a real character that fits her apparent limitations like a glove. Only in Hollywood would Gerwig be considered "fat", but she has a kind of fleshy quality, coupled with her character's apparent inability to think of herself as a person who deserves to look nice (her own mantra is "You are of value", a depressingly clinical sort of positive reinforcement), and just as Stiller's physical presence largely define Roger, so does Gerwig's define Florence; if he's strung out, she's slumped. We never feel quite as much need to blame her for her sins as we do him, but at the same time, she's harder to sympathise with; she projects so little personality into the universe that it's difficult to care about her.

The ways that Baumbach explores these worn-out characters is varied and deceptively simple: through music (some of it provided by James Murphy, some of it pre-existing pop music; there's a magnificent scene set to "Admiral Halsey" by Paul and Linda McCartney), though Harris Savides's outstanding cinematography, which renders Los Angeles as a dusty, grainy, indistinct place where it's always warm and never hot, and certainly never livable (I cannot name a soul who uses Southern California's unique light better than Savides), and through a careful use of close-ups: not indiscriminately and messily, but as punctuation. The fabric of the movie keeps pushing us in towards Roger, never letting us a safe distance, always making us share in his nastiness along with his victims. It is merciless, and therefore extremely effective.

All in all: a fun night at the movies! That's the only real problem though; along with Margot at the Wedding (and unlike The Squid and the Whale, or Baumbach's earlier, non-misanthropic features), I can't really say what Greenberg does of especial value to the randomly-selected viewer. A good character study is arguably its own reward, of course, and we certainly do get to learn quite a lot about human behavior from Greenberg, most of it unpleasant. This is not a film about redemption or happy romance; though it ends in such a way that we can assume that Roger and Florence might be together, we can't for more than a moment believe that it would be very happy or remotely healthy. The film begins and ends with saying, "This kind of self-destructive person exists, there's not much you can do to save them, only keep them from taking you down too", which is of course the truth. And maybe, as long as Baumbach seems mostly alone amongst American filmmakers in telling that kind of story, he doesn't need to have a better reason for doing so.