Fathoms below

Two devotionals, to start with. Every fan of animation in the United States really should be prostrating ourselves daily in front of a shrine dedicated to GKIDS, who is at this point the only distributor making an effort to bring the best and bravest of feature animation from around the world to get something like a decent theatrical release. Second, every fan of animation in the world should make similar prostrations before director Yuasa Masaaki, who is doing more to push the medium harder and farther than anybody else working in features right now. There's probably a way to hedge that claim, but who do so? Going back to his directorial coming-out party, the 2004 feature film Mind Game, Yuasa has been on some ridiculous other level that has stretched through multiple TV series and, in 2017, a pair of features that GKIDS nabbed for North American distribution, so it all comes full circle.

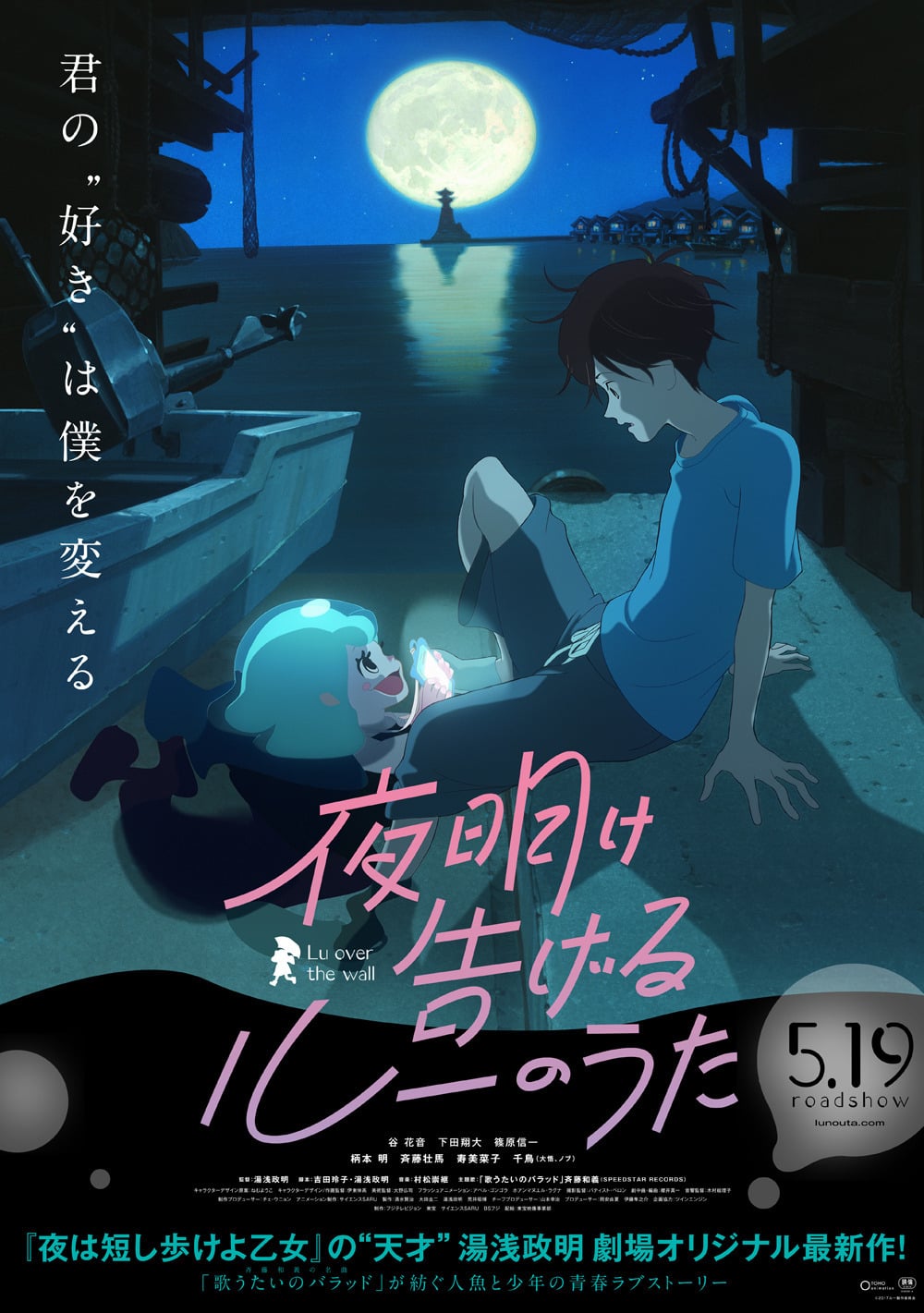

The second of those features, and the first that GKIDS released, is Lu Over the Wall, interesting for at least one additional reason on top of everything else: it is, I believe, Yuasa's first project that seems to have been made substantially with kids in mind. It's pure fairy tale stuff, centering on a small fishing town, Hinashi, whose population has spent many years living in an uneasy stasis with the local population of fish-people, or ningyo (the word is perpetually translated as "mermaid" and related terms, but it means something just a little bit to the side of the European folkloric creature). It has been a couple of generations since the last ningyo-human interactions, which are remembered with great bitterness by the old folks who lost loved ones to the hungry sea beasts. None of this matters very much to our protagonist, Kai (Shimoda Shota): he's an adolescent, just wrapping up his last year of junior high school, and he hates Hinashi very much, having just moved there with his divorced father. It appears, honestly that he hates everything very much, in the fashion of a sullen teenager, mixed with a fair amount of precocious ennui that looks very much like depression.

During his alone time, which is almost every waking minute he's not at school, Kai keeps himself busy by creating fairly elaborate multitrack songs and uploading them to the internet. Though he does this anonymously, he still catches the eye of two classmates, Yuho (Kotobuki Minako) and Kunio (Saito Soma), talentless musicians who are nevertheless, with great enthusiasm, putting together a band, SEIREN (which is a direct reference to European-style mermaids). Kai doesn't so much "join" as he never gets around to declining their invitation, and in hardly any time, he's out rehearsing with them on the rock out in the bay that has for many years created a natural fishing ground - now starting to run dry - while also putting them firmly out in ningyo territory. Their first song rouses the attention of one such creature, a small girl ningyo named Lu (Tani Kanon), whose fish tail splits into rudimentary legs as she listens to the song, causing her to joyfully dance about. She also grows incredibly fascinated by Kai, following him back to his home, and using her ability to selectively shape water to insert herself and a large chunk of the sea right into the attic where he's been moping about. In no time at all, Kai has perked up considerably, thrown himself into SEIREN, and introduced Yuho and Kunio to Lu, whose love of human music is shortly to prove just the tip of a very complicated iceberg.

That's the one great big problem with Lu Over the Wall: it has lots of plot. Like, those two paragraphs really are just the exposition, and there are multiple story strands that happen after that. There are at least three distinct conflicts that don't always play nice together, and for about 25 minutes, roughly in the third quarter of a 112-minute film, the conflict goes so far from anything that has gone before or will come again after that I'm honestly at a bit of a loss to explain what Yuasa and co-writer Yoshida Reiko thought they were up to. It's at least never boring, but it gets frankly too complex for what is, after all, in large part just a Japanese re-imagining of Hans Christian Anderson's slender fairy tale The Little Mermaid.

On the other hand, by virtue of having so much stuff, Lu Over the Wall also has a great deal of stuff that is extremely good. There's nothing unreasonably complex here, just a story of a weird little magic being thoroughly enjoying life and inspiring everyone around her to enjoy life also, but part of the film's wonder is that has the contagious energy that Lu herself does. The film is in a state of perpetual movement, with multiple musical sequences with bright, percussive pop that in a very conscious way demands the viewer start bobbing along (Muramatsu Takatsugu composed the lovely score; I'm not sure if he also wrote these poppy interludes). It's kind of just eye and ear candy, though this fact is not unconnected to its narrative and its themes, which are centered on that kids' film chestnut, It Is Good That We All Be Friends and Neighbors. Anyway, the film has terrific momentum, and it spends most of its time finding new ways to redirect that momentum - almost to a fault, it's constantly trying to reinvent itself.

All of this high-energy narrative flow is very much manifest in the animation, and the animation is actually what makes this such a tremendous achievement (as a story, it's a sweet, bouncy fable, but nothing to write home about). Three things, at least, are going on here. One is the very obvious distinction between the present and everything else: Yuasa transforms flashbacks into amazing, boldly-colored swatches of something midway between French Impressionism and a child's crayon drawings. Better still is when these flashbacks shift back into the present-day material, which is the second thing: the film's incredible fluidity. This is not new for Yuasa, by any means: his characters have always had a sort of viscous quality that allowed them exaggerate their expressions and movements to create striking emotional moments, and Lu Over the Wall merely repeats this. To great effect: the mutability of faces and limbs (one thing he's playing at a lot here is to use movement of hands and legs along the Z-axis, with body parts stretching out like something shot with an extreme wide-angle lens so that even a few inches of movement makes the emergent arm loom up grotesquely) in even the most quotidian dramatic scenes creates a strong feeling of otherwordly possibility, while also forcing the characters' inner lives out onto their bodies.

The third thing, and by far the most important, is how the film functions as a declaration of principles for character animation near the end of the second decade of the 21st Century. Lu Over the Wall is a technological chimera: hand-drawn key frames (the major poses that make up a complete movement) have been scanned into Flash, or one of its successor programs more likely, and the in-between frames have been automated that way. Flash animation is, of course, the modern state of the art, for good or ill - and I would say it has been almost all ill. The big problem with Flash is that it creates a certain stability and rigidity of shape: you can't get that wonderful squash-and-stretch fleshiness of the greatest 20th Century character animation, and even the best Flash animation tends to make characters look like they're floating just a bit above the background, detached and weightless. Lu Over the Wall is something of a manifesto of how to make Flash animation look good: and it is, no two ways about it, the best-looking Flash animation I have ever seen.

There's a little bit of a cheat involved: one thing all that constant momentum does is to make the weightlessness of the form seem deliberate and effective. But there's also some creative manipulation of the program, forcing it to adapt to the animator's keyframes, and thus find a way to replicate the flexibility of traditional animation techniques while maintaining the efficiency and stability that, I guess, are the reason anybody would want to use Flash in the first place. As a proof of concept, Yuasa goes all the way back to the '30s: the character designs, and much of the character movement, are right out of the golden age of American short cartooning, with limbs of pure rubber and faces that exist as little more than two dots and a big slash for a mouth. It's a visceral reminder of the great beauty and pleasure of pure kinetic movement and disregard for physical limitation that are the cornerstones of animation, and some of the most shocking, exciting character animation I've seen in a very, very long time. That might not be completely enough to wash out the taste of the needlessly convoluted script, but it goes a long way.

The second of those features, and the first that GKIDS released, is Lu Over the Wall, interesting for at least one additional reason on top of everything else: it is, I believe, Yuasa's first project that seems to have been made substantially with kids in mind. It's pure fairy tale stuff, centering on a small fishing town, Hinashi, whose population has spent many years living in an uneasy stasis with the local population of fish-people, or ningyo (the word is perpetually translated as "mermaid" and related terms, but it means something just a little bit to the side of the European folkloric creature). It has been a couple of generations since the last ningyo-human interactions, which are remembered with great bitterness by the old folks who lost loved ones to the hungry sea beasts. None of this matters very much to our protagonist, Kai (Shimoda Shota): he's an adolescent, just wrapping up his last year of junior high school, and he hates Hinashi very much, having just moved there with his divorced father. It appears, honestly that he hates everything very much, in the fashion of a sullen teenager, mixed with a fair amount of precocious ennui that looks very much like depression.

During his alone time, which is almost every waking minute he's not at school, Kai keeps himself busy by creating fairly elaborate multitrack songs and uploading them to the internet. Though he does this anonymously, he still catches the eye of two classmates, Yuho (Kotobuki Minako) and Kunio (Saito Soma), talentless musicians who are nevertheless, with great enthusiasm, putting together a band, SEIREN (which is a direct reference to European-style mermaids). Kai doesn't so much "join" as he never gets around to declining their invitation, and in hardly any time, he's out rehearsing with them on the rock out in the bay that has for many years created a natural fishing ground - now starting to run dry - while also putting them firmly out in ningyo territory. Their first song rouses the attention of one such creature, a small girl ningyo named Lu (Tani Kanon), whose fish tail splits into rudimentary legs as she listens to the song, causing her to joyfully dance about. She also grows incredibly fascinated by Kai, following him back to his home, and using her ability to selectively shape water to insert herself and a large chunk of the sea right into the attic where he's been moping about. In no time at all, Kai has perked up considerably, thrown himself into SEIREN, and introduced Yuho and Kunio to Lu, whose love of human music is shortly to prove just the tip of a very complicated iceberg.

That's the one great big problem with Lu Over the Wall: it has lots of plot. Like, those two paragraphs really are just the exposition, and there are multiple story strands that happen after that. There are at least three distinct conflicts that don't always play nice together, and for about 25 minutes, roughly in the third quarter of a 112-minute film, the conflict goes so far from anything that has gone before or will come again after that I'm honestly at a bit of a loss to explain what Yuasa and co-writer Yoshida Reiko thought they were up to. It's at least never boring, but it gets frankly too complex for what is, after all, in large part just a Japanese re-imagining of Hans Christian Anderson's slender fairy tale The Little Mermaid.

On the other hand, by virtue of having so much stuff, Lu Over the Wall also has a great deal of stuff that is extremely good. There's nothing unreasonably complex here, just a story of a weird little magic being thoroughly enjoying life and inspiring everyone around her to enjoy life also, but part of the film's wonder is that has the contagious energy that Lu herself does. The film is in a state of perpetual movement, with multiple musical sequences with bright, percussive pop that in a very conscious way demands the viewer start bobbing along (Muramatsu Takatsugu composed the lovely score; I'm not sure if he also wrote these poppy interludes). It's kind of just eye and ear candy, though this fact is not unconnected to its narrative and its themes, which are centered on that kids' film chestnut, It Is Good That We All Be Friends and Neighbors. Anyway, the film has terrific momentum, and it spends most of its time finding new ways to redirect that momentum - almost to a fault, it's constantly trying to reinvent itself.

All of this high-energy narrative flow is very much manifest in the animation, and the animation is actually what makes this such a tremendous achievement (as a story, it's a sweet, bouncy fable, but nothing to write home about). Three things, at least, are going on here. One is the very obvious distinction between the present and everything else: Yuasa transforms flashbacks into amazing, boldly-colored swatches of something midway between French Impressionism and a child's crayon drawings. Better still is when these flashbacks shift back into the present-day material, which is the second thing: the film's incredible fluidity. This is not new for Yuasa, by any means: his characters have always had a sort of viscous quality that allowed them exaggerate their expressions and movements to create striking emotional moments, and Lu Over the Wall merely repeats this. To great effect: the mutability of faces and limbs (one thing he's playing at a lot here is to use movement of hands and legs along the Z-axis, with body parts stretching out like something shot with an extreme wide-angle lens so that even a few inches of movement makes the emergent arm loom up grotesquely) in even the most quotidian dramatic scenes creates a strong feeling of otherwordly possibility, while also forcing the characters' inner lives out onto their bodies.

The third thing, and by far the most important, is how the film functions as a declaration of principles for character animation near the end of the second decade of the 21st Century. Lu Over the Wall is a technological chimera: hand-drawn key frames (the major poses that make up a complete movement) have been scanned into Flash, or one of its successor programs more likely, and the in-between frames have been automated that way. Flash animation is, of course, the modern state of the art, for good or ill - and I would say it has been almost all ill. The big problem with Flash is that it creates a certain stability and rigidity of shape: you can't get that wonderful squash-and-stretch fleshiness of the greatest 20th Century character animation, and even the best Flash animation tends to make characters look like they're floating just a bit above the background, detached and weightless. Lu Over the Wall is something of a manifesto of how to make Flash animation look good: and it is, no two ways about it, the best-looking Flash animation I have ever seen.

There's a little bit of a cheat involved: one thing all that constant momentum does is to make the weightlessness of the form seem deliberate and effective. But there's also some creative manipulation of the program, forcing it to adapt to the animator's keyframes, and thus find a way to replicate the flexibility of traditional animation techniques while maintaining the efficiency and stability that, I guess, are the reason anybody would want to use Flash in the first place. As a proof of concept, Yuasa goes all the way back to the '30s: the character designs, and much of the character movement, are right out of the golden age of American short cartooning, with limbs of pure rubber and faces that exist as little more than two dots and a big slash for a mouth. It's a visceral reminder of the great beauty and pleasure of pure kinetic movement and disregard for physical limitation that are the cornerstones of animation, and some of the most shocking, exciting character animation I've seen in a very, very long time. That might not be completely enough to wash out the taste of the needlessly convoluted script, but it goes a long way.